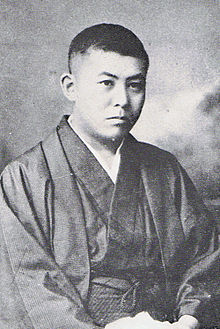

Tanizaki Jun'ichirō

Tanizaki Jun'ichirō ( Japanese 谷 崎 潤 一郎 ; * July 24, 1886 in Nihonbashi , Tokyo city (today: Chūō , Tokyo ); † July 30, 1965 ) was a Japanese writer.

Life

His parents both came from old merchant families. Although the father managed the fortunes built up by his grandfather and the family was therefore often plagued by financial difficulties, Tanizaki had a carefree childhood. Tanizaki, meanwhile, already attracted attention at school with her brilliant stylistic achievements. He took private tuition in English and Classical Chinese and passed the entrance exam to the Imperial University of Tokyo in 1908 . In addition to studying English and Japanese literature, Tanizaki also began to write during this time. In 1910 he founded the magazine Shinshishō ( 新 思潮 , New Current) with fellow students , in which he also published his first story Shisei (tattoo). Without a degree, he decided to pursue a career as a writer and immediately had great success with his first stories.

In 1915 he married Chiyo Ishikawa, but he soon got tired of this marriage and lived with his sister-in-law for a while. This coexistence later formed the subject of his novel Naomi or an insatiable love . Tanizaki traveled to China twice in 1918 and 1926. After the earthquake disaster in 1923 , he settled in western Japan with his wife and daughter. Constant changes of residence and the tense financial situation led to the divorce in 1930. The following year Tanizaki married the publishing editor Tomiko Furukawa; but this marriage, too, was divorced two years later. His first wife and her three sisters also formed the template for his later masterpiece The Makioka Sisters (1944–1948).

Tanizaki was an extremely productive writer throughout his life: he published 119 works, and in 1921 the first complete edition of his works appeared in five volumes. He was in talks for the Nobel Prize for Literature and received a number of literary awards. He was a member of the Imperial and Japanese Academy of Arts and holder of the cultural order . His great novels, which create the contrast between tradition and modernity in ever new problems, have been translated into many languages.

End of July 1965 died Tanizaki from acute heart and kidney failure at his home in Yugawara in the Kanagawa Prefecture . The Tanizaki Jun'ichirō Prize , endowed with 1 million yen, has been awarded in his honor since 1965 .

Prizes and awards

- 1947 Mainichi Culture Prize for Sasameyuki ( 細 雪 , German: The Makioka Sisters)

- 1948 Asahi Prize for Sasameyuki ( 細 雪 , Eng . The Makioka Sisters)

- 1964 honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

Classification in literary history

Tanizaki's work spans the Meiji , Taishō, and Shōwa epochs. After Japan had received an almost confusing number of literary movements from Europe at a tremendous speed at the beginning of modernity, the literary world began to consolidate itself in Japanese naturalism at the time of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 . The medium par excellence of naturalism was the autobiographically colored Shishōsetsu ( 私 小説 , first- person novel). In the search for the true essence of man, naturalism, like its European predecessor, elevated the faithful representation of reality to the primacy of representation. In Japan, the dictate of mimesis led to a form of representation of reality that was tantamount to an autobiographical self- exposure of the author.

Not least because Japanese literature has developed in wave-like phases since the Meiji period out of enthusiasm for the foreign West and a return to one's own traditions and roots, but also out of the burgeoning social problems of the time, it also existed at the same time as naturalism a countermovement made up of various currents. This also includes the aestheticism to which Tanizaki's work can be assigned. Tanizaki, who as a child often attended the kabuki theater and was excellently trained in Japanese, classical Chinese and European literature, favored the enjoyment of the creative act and the invented story, contrary to naturalism. Tanizaki not only read the popular and fantastic short stories by Ueda Akinaris , Takizawa Bakins and Kōda Rohan with fascination , he also deals with Plato , Schopenhauer , Shakespeare and Carlyle . The influence of the Western symbolists Poe , Baudelaire and Wilde can also be clearly seen in his stories . While the 20s of his work were still shaped by a fascination for the West, the 30s were shaped by the search for the genuinely Japanese tradition. Tanizaki too, like almost all of his writing contemporaries, got entangled in the propaganda of militarism in the 1940s.

His first story, Tattoo, is about Seikichi, who tattoos a spider on the back of a young woman. Already in this story Tanizaki unfolds a theme that is leitmotiv for his work: the subtle power play of ruling and being ruled, the mutual entanglement of desire up to bondage. Tanizaki masterfully exploits the versatility and homophony of the Japanese language to condense allusions and generate complex associations. This linguistic sophistication makes it a demanding task for every translator. The combination of idealized beauty and physical cruelty have entered Tanizaki also the attribute of the diabolical .

Works

| year | Japanese title | German title |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 |

刺青 Shisei |

tattoo |

| 1918 |

金 と 銀 Kin to Gin |

gold and silver |

| 1924 |

痴人 の 愛 Chijin no Ai |

Naomi, or an insatiable love |

| 1927 |

饒舌 録 Jōzetsu roku |

Chronicle of Talkativeness (essay) |

| 1928- 1930 |

卍 Manji |

|

| 1929 |

蓼 喰 ふ 蟲 Tade kuu mushi |

Island of the Dolls |

| 1930 |

懶惰 の 説 Randa no setsu |

Reflections on Indolence (essay) |

| 1931 |

恋愛 及 び 色情 Ren'ai oyobi shikijō |

Love and sensuality (essay) |

| 1931 |

吉野 葛 Yoshino kuzu |

|

| 1932 |

蘆 刈 り Ashikari |

|

| 1932 |

倚 松 庵 随筆 Ishōan zuihitsu |

Notes from the Ishōan House (collection of essays) |

| 1932 |

青春 物語 Seishun monogatari |

Report from my youth (essay) |

| 1932 |

私 の 見 た 大阪 及 び 大阪 人 Watashi no mita Ōsaka oyobi Ōsakajin |

Osaka and the people of Osaka as I saw them (essay) |

| 1933 |

春 琴 抄 Shunkinshō |

Shunkinshō - biography of the spring harp |

| 1933 |

芸 談 Geidan |

Praise to Mastery (essay) |

| 1933 |

陰 翳 礼 讃 In'ei Raisan |

Praise to the shadow . Design of a Japanese Aesthetic (Essay) |

| 1934 |

文章 読 本 Bunshō tokuhon |

Style Reader (Essay) |

| 1934 |

東京 を お も う Tōkyō o omou |

Reflecting on Tōkyō (essay) |

| 1935 |

摂 陽 随筆 Setsuyō zuihitsu |

Notes from Setsuyō (Setsuyō = Ōsaka; collection of essays) |

| 1935 |

武 州 公 秘 話 Bushūkō Hiwa |

The secret story of the Prince of Musashi |

| 1936 |

猫 と 庄 造 と 二人 の お ん な Neko to Shōzō to Futari no Onna |

A cat, a man and two women |

| 1943- 1948 |

細 雪 Sasameyuki |

The Makioka sisters |

| 1949 |

少将 滋 幹 の 母 Shōshō Shigemoto no haha |

|

| 1956 |

鍵 Kagi |

The key |

| 1957 |

幼 少 時代 Yōshō Jidai |

|

| 1961 |

瘋癲 老人 日記 Fūten Rōjin Nikki |

Diary of an old fool |

Translations

- Novels

- Gold and silver. Translated by Uwe Hohmann and Christian Uhl, Leipzig 2003.

- Naomi, or an insatiable love. Translated by Oscar Benl , Reinbek near Hamburg 1970.

- Island of the Dolls from the American by Curt Meyer-Clason, Esslingen 1957.

- The secret story of the Prince of Musashi. Translated by Josef Bohaczek, Frankfurt / Main, Leipzig 1994.

- A cat, a man and two women. Translated by Josef Bohaczek, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1996.

- The Makioka sisters. Translated by Sachiko Yatsushiro, collaboration: Ulla Hengst, Reinbek near Hamburg 1964.

- The key . Translated by Sachiko Yatsushiro and Gerhard Knauss , Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1961. New translation by Katja Cassing and Jürgen Stalph, cass Verlag, Löhne 2017, ISBN 978-3-944751-13-9 .

- Diary of an old fool. Translated by Oscar Benl, Reinbek near Hamburg 1966

- stories

- A little kingdom . Translated by Jürgen Berndt. In: Dreams of Ten Nights. Japanese narratives of the 20th century. Eduard Klopfenstein, Theseus Verlag, Munich 1992. ISBN 3-85936-057-4

- Shunkinshō - biography of the spring harp. Translated by Walter Donat, in: Walter Donat (Ed.), The five-storey pagoda. Japanese storytellers of the 20th century, Düsseldorf, Cologne 1960.

- Tattoo. Translated by Heinz Brasch, in: Margarete Donath (Hrsg.), Japan told, Frankfurt / Main 1969. (also as The Sacrifice in the book Mond auf dem Wasser . Berlin 1978)

- The thief , in: Dragons and dead faces , ed. v. J. van de Wetering. Rowohlt 1993. ISBN 3-499-43036-3 (also as I in the volume Japanese crime stories . Stuttgart 1985)

- Essays

- Praise to the shadow . Design of a Japanese aesthetic. Essay, translated by Eduard Klopfenstein, Manesse, Zurich 2010, ISBN 978-3-7175-4082-3

- Praise the championship . Essay, translated by Eduard Klopfenstein. Manesse, Zurich 2010, ISBN 978-3-7175-4079-3

- Love and sensuality . Essay, translated by Eduard Klopfenstein. Manesse, Zurich 2011, ISBN 978-3-7175-4080-9

Filmography

- 1920 Amachua kurabu (Amateur Club), screenplay: Tanizaki Jun'ichirō, director: Kurihara Kisaburō

- 1920 Katsushika Sunago based on the story by Kyōka Izumi , screenplay: Tanizaki Jun'ichirō, director: Kurihara Kisaburō

- 1921 Hinamatsuri no yoru (The evening at the Hina Matsuri festival), screenplay: Tanizaki Jun'ichirō, director: Kurihara Kisaburō

- 1921 Jasei no in (The love of a snake), screenplay: Tanizaki Jun'ichirō, director: Kurihara Kisaburō

Quotes

- "The young tattoo artist's soul had dissolved into the ink; now it seeped into the girl's skin." (from the story: The tattoo; in Das große Japan-Lesebuch , Munich 1990, p. 19)

- "If I can only be beautiful, I will endure whatever, whatever, she replied, forcing herself to smile regardless of the pain in her body." (from the story: The tattoo; in: Das große Japan-Lesebuch , Munich 1990, p. 21)

See also

Web links

- Compilation of Tanizakis works (English)

- Webpage of the Tanizaki Museum in Ashiya (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit: The Japanese Literature of Modernism, Munich edition text + kritik, 2000, p. 59

- ↑ Not to be confused with the narrative perspective of the first-person narration .

- ↑ Not to be confused with the aesthetics of Europe as a sub-discipline of philosophy.

- ↑ IMDB

- ↑ IMDB

- ↑ IMDB

- ↑ IMDB

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tanizaki, Jun'ichirō |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | 谷 崎 潤 一郎 (Japanese); Tanizaki, Junichirō |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Japanese writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 24, 1886 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Nihombashi-ku (Tokyo) , City of Tokyo , today: Chūō , Tokyo |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 30, 1965 |