Congress of Erzurum

The Congress of Erzurum ( Turkish Erzurum Kongresi ) was a conference of members of the Turkish national movement that took place from July 23 to August 4, 1919 in Erzurum . Delegates from six Eastern Vilayets of the Ottoman Empire attended the congress, many of which were occupied by Allied troops. The Congress played an important role in forging a national identity for modern Turkey.

background

Armistice of Moudros

In the months before the end of the First World War , the Ottoman Empire had undergone extensive restructuring. In July 1918 Sultan Mehmed V and his half-brother Mehmed VI died. followed the throne. The members of the government, who came from the party-like Committee for Unity and Progress and who formed the Ottoman government between 1913 and 1918, had resigned from office and fled the country shortly afterwards. Successful Allied offensives in Salonika on the Macedonian front posed a direct threat to the Ottoman capital Constantinople . Mehmed VI. appointed Ahmed İzzet Pasha Grand Vizier and instructed him to negotiate an armistice with the Allies and thus to end the participation of the Ottoman Empire in the war. On October 30, 1918, the Ottoman Empire, represented by Minister of the Navy Rauf Orbay, and the Allies, represented by British Admiral Somerset Gough-Calthorpe, signed an armistice. The armistice ended the Ottoman participation in the war.

Allied Occupation

The victors of the First World War soon began with the military occupation and the partition of the Turkish Empire. The Ottoman border provinces in Arabia and Palestine were already under the control of the British and French. After the armistice was signed, Allied warships took up positions off the coast of Constantinople in the straits of the Dardanelles and the Bosporus in order to secure them. In February 1919, the French general Louis Félix Marie Franchet d'Espèrey led a Greek occupation force into the city after French, British and Italian troops had already been stationed in the city. The Anatolian province of Antalya was occupied by the Italians, and Cilicia and the Vilayet Adana were controlled by French troops advancing from Syria. At the end of 1918, however, small resistance groups called societies for the defense of rights ( Müdâfaa-i hukuk cemiyetleri ) began to form.

Greek occupation

The turning point in the Turkish national movement began on May 14, 1919, when Greek occupation forces occupied the city of Smyrna (now Izmir). There was a sizable Greek community in and around the city. The Greek armed forces had previously expressed their clear intention of permanently annexing the province of Izmir. The Greeks immediately encountered violent protests and resistance from the Turkish population, many of whom had obtained weapons from secret camps. The news of the Greek occupation quickly spread throughout the empire and fueled the Turkish aversion to the Allied occupation.

Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and the Turkish War of Liberation

While the Greek armed forces tried to consolidate their position in Izmir, the successful Ottoman officer Mustafa Kemal was appointed by the Sultan at the express request of the Allies to enforce peace and order and dissolve the remaining Ottoman regiments. On May 19, Kemal arrived in the port city of Samsun on the Black Sea.

Despite the Ottoman orders, Kemal began organizing a Turkish national resistance movement to protect the territories of Anatolia from the invasion of the occupying powers. On June 28, the British Deputy High Commissioner in Constantinople, Admiral Richard Webb , wrote a letter to Sir Richard Graham about the Turkish resistance in the east of the Ottoman Empire and the burgeoning Greco-Turkish conflict: “It is very serious now, and of course everything goes back to the time of the occupation of Smyrna by the Greek troops [...] Up to the occupation of Smyrna we made quite good progress. The Turk was of course a bit difficult, but we were able to gradually dismiss the bad Valis, Mutesssarifs, etc., and I think we could have got along well to a peace without much effort [...] But now everything is different. Greeks and Turks kill each other in Vilayet Aydin. Mustafa Kemal is busy around Samsun and so far refuses to cooperate. Raouf Bey and one or two others are with Bandırma and there is evidence to suggest that the War Ministry here in Constantinople is the organizing center of the unrest. "

Preliminary meeting in Amasya

In June 1919, Kemal spoke to prominent Turkish statesmen and officers such as Ali Fuat Cebesoy and Rauf Orbay at a secret meeting in the city of Amasya and also instructed the Turkish general Kâzım Karabekir , who commanded the 15th Army Corps near Erzurum and, early on, the Vilayat-i Sarkiye Muidafaa-i Hukuk-u Milliye Cemiyeti ( Society for the Defense of National Rights in the Eastern Provinces ).

The meeting laid the foundation for the Turkish national movement and the subsequent Erzurum Congress.

After the meeting in Amasya, Kemal telegraphed a circular to many Turkish civil and military persons presenting the ideas of the Turkish nationalists:

- The integrity of the country and the independence of the nation are at risk

- The central government is not performing the duties for which it is responsible. As a result, the nation is not perceived as such.

- Only the will and determination of the nation can save the nation's independence.

In the meantime, General Kâzım Karabekir began sending out invitations to a meeting of Turkish-East Anatolian delegates in the city of Erzurum. Kemal came to Erzurum to start organizing the meeting of Turkish delegates. To avoid any charges of treason or rebellion against the still legitimate Ottoman Sultanate, Kemal resigned from his post and gave up the title of Pasha. In order to maintain the appearance of legitimacy, Kemal was supported by the official Society for the Defense of the Rights of Eastern Anatolia , an association founded in March 1919 in Erzurum, which was legally registered and recognized by the Vilâyet Erzurum.

Course of the Congress

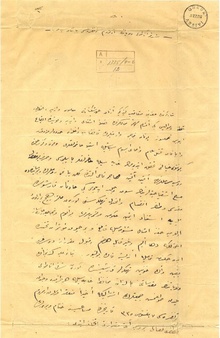

On July 23, 1919, 56 delegates from the Vilâyets of Bitlis , Erzurum , Sivas , Trabzon and Van met in Erzurum at the invitation of Mustafa Kemal and Kâzım Karabekir. The conference was held in the building that once housed the Sanasaryan Koleji , a prestigious school and a former regional center of Armenian culture and education in the years leading up to the Armenian genocide .

On the first day the delegates elected Mustafa Kemal as chairman of the congress. The Congress made a number of important decisions that would shape future action by the Turks in the war of liberation. Congress reaffirmed the provinces' wishes to remain in the Ottoman Empire rather than being divided up by the Allies. They refused to recognize a League of Nations mandate for the empire and opposed special rights for Greeks or Armenians . It was decided to oppose such measures should any attempt be made to implement them. The Congress also drafted a first version of the Misak-ı Millî (National Pact ), which was later to be passed in Sivas. Before the congress ended on August 17th, the delegates elected the members for a Representative Committee ( Heyet-i Temsiliye ) with Kemal as chairman, as well as Rauf Orbay, Bekir Sami Bey , Refet Bey , Kara Vâsıf Bey and Mazhar Müfit Bey .

During the Congress, General Kâzım Karabekir was directed by the Sultanate to arrest Kemal and Rauf and to take over Kemal's position as Inspector General of the Eastern Provinces. However, he resisted the government in Constantinople and refused to carry out the arrest.

The following decisions were made:

- The territorial integrity and indivisibility of the home country must be protected.

- The nation would resist any foreign occupation.

- A provisional government would be formed when the government in Constantinople was unable to maintain nation independence and unity.

- The aim is to combine the national forces into one ruling factor and to establish the will of the nation as a sovereign power.

- The nation does not accept the status of a League of Nations mandate or a protectorate.

Effects

The Erzurum Congress was followed by a congress in Sivas , attended by delegates from all over the empire. The Sivas Congress applied the ideas presented at the Erzurum Congress to all of Anatolia and Rumelia . The Society for the Defense of the National Rights of Eastern Anatolia became the Society for the Defense of the Rights of Anatolia and Rumelia . The Erzurum Congress was the first conference of Turkish delegates during the Turkish War of Independence, which led to the abolition of the Ottoman Sultanate. Although the Congress in Sivas expressed its support for the Sultan, it made it clear that it was of the opinion that the government and the Grand Vizier in Constantinople could not protect the rights of Turkish citizens and the state territory. Congress established Turkish nationalism and played an essential role in defining a new Turkish national identity for the emerging Republic of Turkey .

Individual evidence

- ^ Richard G. Hovannisian: The Republic of Armenia: The First Year, 1918-1919 . Volume 1, University of California Press, Berkeley 1971, ISBN 0-520-01984-9 , pp. 434-437

- ^ A b Carter Vaughn Findley: Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity . Yale University Press, 2010, p. 215

- ^ Bernard Lewis: The Emergence of Modern Turkey . Oxford University Press, 1968, p. 239

- ^ Lewis (1968), p. 240

- ^ Lewis (1968), p. 246

- ↑ Michael Llewellyn-Smith : Ionian Vision: Greece in Asia Minor 1919-1922 . St. Martin's Press, New York 1973, p. 88

- ^ Llewellyn Smith (1973), p. 90

- ^ Llewellyn Smith (1973), p. 103

- ↑ Documents on British Foreign Policy, IV, No. 433, Webb to Sir R. Graham, June 28, 1919

- ^ Lewis (1968), p. 247

- ↑ Erik Jan Zürcher: Young Turk Memoirs as a Historical Source: Kazim Karabekir's "Istikal Harbimiz" . In: Middle Eastern Studies , Vol. 22, No. 4 (October 1986), pp. 562-570, here p. 564

- ^ Lewis (1968), p. 247

- ^ Lewis (1968), p. 248

- ^ Lewis (1968), p. 248

- ↑ Hovannisian (1971), p. 435 f.

- ↑ Hovannisian (1971), p. 436

- ↑ Erzurum Kongresi'nin bildirisi ve kararları , TC Başbakanlık Atatürk Kültür, Dil ve Tarih Yüksek Kurumu, Ataturk Araştırma Merkezi Başkanlığı, accessed on May 4, 2019 (Turkish)

- ^ Lewis (1968), p. 248

- ↑ Eric J. Zürcher: Turkey: A Modern History . IB Tauris, London 2004, p. 150

- ^ Lewis (1968), p. 248

- ↑ Erik Jan Zürcher: Young Turk Memoirs as a Historical Source: Kazim Karabekir's "Istikal Harbimiz" . In: Middle Eastern Studies , Vol. 22, No. 4 (October 1986), pp. 562-570, here p. 567

- ↑ M. Fahrettin Kırzıoğlu: Bütünüyle Erzurum Kongresi , 1993, p 131

- ↑ Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu: History of the Ottoman state, society & civilization . 2001, p. 827

- ↑ Lewis (1968), p. 248 f.

- ^ Lewis (1968), p. 249