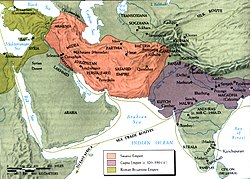

Kushano-Sassanids

The Persian Sassanid Empire had its domain during the 3rd / 4th centuries. Century at the expense of the Kushan extended to the northwest of the Indian subcontinent . The Sassanids installed governors in this area, who are accordingly referred to as Kuschano-Sassanids (more rarely as Indo-Sassanids ); this relates above all to the coinage of the local Sassanid governors ( Kushanshahs ). In the late 4th / early 5th century, the rule of the Sassanids in this area was pushed back by the invasion of the Iranian Huns (see Kidarites , Alchon , Nezak and Hephthalites ). However, the Sassanids were able to regain some areas after the destruction of the Hephthalite Empire around 560. The Sassanid Empire finally collapsed in the 7th century in the course of Islamic expansion .

history

First period

After the victory over the Parthians , the Sassanids extended, perhaps during the reign of Ardashir I. , her power field as far as Bactria . Under Shapur I (240–270) the border of the empire was expanded into what is now Pakistan . So the Kushan lost their western territories (including Bactria and Gandhara ) to the Sassanids. They repeatedly installed their princes as governors in the east, who bore the title of Kushanshah ("rulers of the Kushans"). Many of them, like a brother of Bahram II named Hormizd, took advantage of this position to attempt usurpation.

The fall of the Kushan and their defeat by the Sassanids led to the rise of the indigenous Indian dynasty of the Gupta in the 4th century. In the early 5th century, the dating is problematic, the Hephthalites Bactria and Gandhara took over and were thus able to displace the Sassanids for a time.

Second period

In the middle of the 6th century there was an alliance between the Sassanids under Chosrau I and the Gök Turks under Sizabulos († 576). As a result, the Hephtalites were attacked and defeated from different sides between around 560 (although remnants of their rule remained in present-day Afghanistan ). The area was divided between the Turks and the Persians and the empire was temporarily restored.

In the middle of the 7th century, the Sassanid Empire fell as a result of the Arab conquest. Sindh remained independent until the early 8th century. The Kuschano Hephthalites were replaced by the Hindu Shahi in the middle of the 8th century .

religion

The Prophet Mani , founder of Manichaeism , followed the Sassanid expansion to the east, which brought him into contact with the Buddhist culture of Ghandarra. He is said to have lived and taught in Bamiyan for some time. There were found some religious paintings dedicated to him. He is also said to have sailed through the Indus around 240 and 241 respectively and converted the Buddhist King Turan Shah of India.

Kartir , a high Zoroastrian priest who has served as an advisor to at least three of the previous kings, called for the persecution of Jews , Buddhists , Hindus, as well as native and Greek Christians and Manicheans , who were mainly resident in the eastern territories. The persecutions ceased under the rule of Narseh (293-302).

art

The Kuschano-Sassanids traded in goods such as silver articles and textiles, which the Sassanid rulers represented in the hunt or in the administration of justice. The model of Sassanid art had a great influence on that of the Kushan. This persisted for several centuries on the northwest of the Indian subcontinent.

swell

The history of the empire can almost only be deduced from the coins and is accordingly problematic. There are few direct written sources on this. The coins are clearly Sassanid, but there are also Kushan features. The front usually shows a picture of the respective ruler with his headdress, on the back either the Indian god Shiva appears together with his bull Nandi or a Zoroastrian age of fire is depicted. The legends are in Brahmi , Pahlavi and Bactrian .

The last recorded Kushanshah was probably a brother of Shapur II , who was present at the siege of Amida in 359.

The main Kushano-Sassanid rulers

- Ardaschir I. Sassanid king and "Kushanshah" (approx. 230–250) coin

- Peroz I. "Kushanshah" (approx. 250–265) coin

- Hormizd I. "Kushanshah" (approx. 265–295) coin

- Hormizd II. "Kushanshah" (approx. 295–300)

- Peroz II. "Kushanshah" (approx. 300–325) coin

- Shapur II. Sassanid king and "Kushanshah" (approx. 325) coin

- Bahram I. "Kushanshah" (approx. 325–350) coin

- Peroz III. "Kushanshah" (approx. 350) coin

literature

- AH Dani, BA Litvinsky: The Kushano-Sasanian kingdom . In: BA Litvinsky (Ed.): The crossroads of civilizations. AD 250 to 750 . Unesco, Paris 1996, ISBN 9-231-03211-9 ( History of Civilizations of Central Asia 3), pp. 103-118.

- Nicholas Sims-Williams: The Sasanians in the East. A Bactrian archive from northern Afghanistan. In: Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis, Sarah Stewart (Eds.): The Sasanian Era . IB Tauris, London 2008, ISBN 978-1-84511-690-3 , pp. 88-102.

- Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods . 2 parts. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1983 ( The Cambridge History of Iran 3, Part 1, ISBN 0-521-20092-X ; Part 2, ISBN 0-521-24693-8 ).

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Étienne de La Vaissière: Kushanshas, History , in: Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ Wolfgang-Ekkehard Scharlipp: The early Turks in Central Asia . Darmstadt 1992, p. 25.

- ↑ This is how one can at least interpret Ammianus Marcellinus 19.1, since the crown described there does not fit on the crown of Shapur II, which is depicted on coins. See ADH Bivar, The History of Eastern Iran , in: E. Yarshater, The Cambridge History of Iran , Vol. 3, pp. 181ff., Here especially pp. 209ff.