Sassanid art

The term Sassanid art denotes Iranian art from the 3rd to the 7th century AD.

In the year 226 was the last Parthian king of Ardashir I. defeated. The Sassanid Empire that had now arisen was to exist for a good four hundred years and only perish as a result of the Islamic expansion in the middle of the 7th century. A new era began in Iran and Mesopotamia , which tried in many ways to tie in with Achaemenid traditions. This also applies to the artistic creation of the new rulers. Nevertheless, various other (including Western) influences can also be identified, including the art of the otherwise rather despised Parthians and the Mediterranean .

General

The art of the Sassanids is mainly characterized by the architecture, the relief and the Toreutic. Compared to its position among the Parthians, free sculpture is becoming less important. There are also outstanding achievements in glyptics and painting .

Sassanid art is a decidedly courtly and knightly art. The image of the ruler dominates many surviving works. Hunting and fighting scenes were particularly popular. Representations are often arranged like a coat of arms, which in turn should have a strong influence on artistic creation in Europe and East Asia. While the previous Parthian art mainly preferred the front view, in narrative representations of Sassanid art the figures are again often shown in profile or in a three-quarter view. But frontal views also occur.

Round sculpture

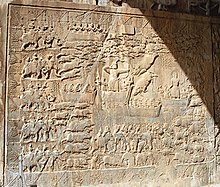

Rock reliefs

The most notable achievements of Sassanid art include a number of monumental rock reliefs, around 30 or so royal ones. With one exception, they can all be found in the province of Fars . This is the area from which the ruling family of the Sassanids came. With a few exceptions, the reliefs come from rulers of the 3rd and the beginning of the 4th century. They celebrate certain major government events. Most are unlabeled. The attribution to a ruler is usually based on the crown shape. Rock reliefs have a long tradition in Persia, which should now reach its peak.

A relief in Naqsch-e Rostam is attached below the Achaemenid royal tombs and is therefore to be understood as a reference to them and also as a government program that should follow on from the old days. Ardaschir I is depicted receiving the ring of lordship from the god Ahuramazda . The god and the ruler are shown strictly in profile. Both are reproduced as good as the same size, which is intended to indicate equality. The relief is modeled very strongly, but is rather reserved in the representation of details. Hellenistic influence can possibly be felt here.

Other reliefs, such as that of Taq Bostan are in a cut in the rock Ivan mounted. On the back wall of this there are almost fully plastic figures. Chosrau II is depicted on a horse in a heavy tank. The scenes on the sides of this ivan depict a royal hunt. The figure of the ruler is shown from the front, while his face is shown in three-quarter view. His figure is oversized and dominates the whole scene, while other figures are shown comparatively small. The composition, with its representation of the landscape and many details such as the king's court, gives a rather picturesque impression and was certainly once painted.

Stucco work

In addition to the rock reliefs, stucco work played a major role under the Sassanids. Many Sassanid buildings are made of brick because of the lack of stone. Since its structures were apparently perceived as unsightly, they were clad with stucco, which also gave the impression that a building was made of stone. Important buildings have therefore been equipped with stucco, but little has been preserved. Excavations have shown that representation rooms in particular were equipped with it, while others were often only whitewashed. Here you will mainly find floral patterns, but also figurative representations, and especially animals are used. The motifs are partially taken from the Greco-Roman world, even if Rome and Persia were rivals throughout late antiquity (see Roman-Persian Wars ). There is evidence from literary sources that Roman artists from the Mediterranean region were deported to the Sassanid Empire and then worked there. You may be responsible for this influence.

painting

Painting, which played an important role, has so far been poorly documented, which is mainly due to an unfavorable research situation. From Mani is known that he founded a painting school. At Hādschiābād in Iran, a mansion was excavated that still contained well-preserved paintings. The walls here were decorated with busts shown in frontal view.

Mosaics

A number of mosaics from Bishapur are noteworthy , which are kept in a classical style and were obviously made by artists from the Mediterranean region.

architecture

Palaces

The Sassanid architecture is characterized above all by spacious, gigantic buildings with wide, high halls.

The Ivan developed by the Parthians was further developed under the Sassanids . It is a large hall open to one side. It is a hall that is not really a closed space, but also not an open courtyard and which is usually covered by a vault.

The best-known and most impressive examples of Sassanid architecture are the kings' palaces, some of which are still standing today. The palace of Firuzabad (Iran) was built by Ardashir I. It is located on a small lake to which the main divan of the building opens. From this, somewhat smaller halls open on both sides, which are also vaulted. Behind the main divan is a hall with a 22 m high dome. There are two more domed halls on either side. Behind it is a courtyard surrounded by halls. The walls of the rooms are divided by niches and once had a rich stucco decoration. There was once a garden around the palace. The garden, the actual palace building and the lake are related to each other and designed as a unit.

The palace in Ctesiphon is also dominated by an ivan, whose vault is still one of the largest. The facade of this palace is also richly structured by niches that once had painted and relief stucco.

urban planning

The Sassanids built numerous new cities with well thought-out city maps. Many of them are circular, which was particularly advantageous in terms of defense technology. The city wall of a round city could enclose a larger area with the same length. In addition, there were also rectangular city systems. These are mostly assigned to Roman architects who were abducted by the Sassanids. Although this is likely, the planning of these cities required Sassanid approval. Rectangular city structures are therefore to be seen as a further possibility of Sassanid city planning.

Firuzabad is a founding of Adashir I and a well-documented example of Sassanid town planning. The city had a diameter of 2 km and was circular. She divided two streets into four parts of the city, which in turn were divided into 5 smaller sectors, thus dividing the whole city into 20 sectors. The detailed planning seems to have continued in the surrounding landscape. Bishapur and Gundischapur , on the other hand, are cities laid out at right angles. Roman craftsmen seem to be attested to Bishapur, since the palace there is decorated with mosaics in the Hellenistic style.

Coins

Coins are a particularly important source. They are easy to date and have been preserved from all periods of the Sassanid period. They bear the name of the respective ruler in Pahlavi and can therefore be used to date other works of art. The obverse usually shows the image of the ruler, sometimes with a son and wife, more rarely with both together. On the back there are various scenes, including an investiture or an altar on which the eternal fire burns. The development of the coin image begins with the rather rigid image of Ardaschir I (224–241), under Shapur I (241–272) the coin image becomes more vivid, only to flatten again afterwards. With Schapur II. (310–379) it becomes more three-dimensional again, although the detail modeling subsides somewhat. However, this will become more important again later. In the following years, the coin images are often strongly stylized and sometimes appear to be registered.

Handicrafts

Toreutics

A special feature of the Sassanid bowls made of silver and gold, on the inner surface of which is a scene carved in relief. Over a hundred copies are known and prove the magnificence of the court, which is also shown in literary terms. Few of them come from excavations, but are mostly incidental finds. Many were found near the Urals in Russia and were traded in this area. The original context, the function and the client of these bowls therefore remain in the dark. Often a ruler is depicted hunting. He usually sits on a horse that moves at a flying gallop . He stabs a dangerous animal like a boar or lion with the sword or shoots a bow and arrow. The face often appears in three-quarter view.

But there are also peaceful depictions, such as depictions of animals and fantasy creatures. Earlier silver bowls usually show the ruler in full relief, the whole bowl dominates. Later, in the 4th and 5th centuries, the main character becomes smaller and the secondary characters become more important.

Another group of metal goods are tall, richly decorated jugs, the shape of which may have been taken from the Mediterranean region.

textiles

There are indications that colorfully decorated fabrics in particular had a special meaning among the Sassanids. The assessment of this art genre brings numerous problems for research, however, as there are few textiles that come from the Sassanid Empire itself and it is not always clear whether the finds outside the empire (e.g. in Egypt ) are imports of the Sassanids, imitations or very own creations. A Sassanid origin is mostly assumed for textiles that are decorated with heraldic animal patterns. Typical are peacocks, rams and other animals that are arranged individually or in pairs within a rosette. The ram was associated with the god of war Verethragna and therefore enjoyed particular popularity in Sassanid art and as a motif on textiles.

outlook

Sassanid art had a strong influence on Islamic art in Persia. The iwan is one of the most characteristic components of Persian architecture . Especially in Central Asia, such as B. in Sogdia art can be traced back directly to the Sassanid.

The heraldic arrangement of animals in pairs can be found in the Byzantine and European Middle Ages. The motif may have been taken directly from the Sassanids. Textiles in particular come into question as carriers of these motifs. In this context some mosaics from the early 6th century from Antioch should be mentioned that take up this motif.

See also

literature

See also the general references in the article Sassanid Empire .

- Kurt Erdmann : The art of Iran at the time of the Sasanids . Berlin 1943, 1969.

- Roman Ghirshman : Iran. Parthians and Sasanids . Munich 1962 (orig. London 1962).

- Prudence Oliver Harper: In search of a cultural identity: monuments and artifacts of the Sasanian Near East, 3rd to 7th century AD New York 2006.

- G. Reza Garosi: The colossal statue of Šāpūrs I in the context of Sasanid sculpture . Verlag Philipp von Zabern , Mainz 2009, ISBN 978-3-8053-4112-7 .

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Massoud Azarnoush: The Sasanian manor house at Hajiabad, Iran , Firenze 1994

- ↑ Lady with a bouquet of flowers ( Memento of the original dated August 11, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Firuzâbâd - A Sassanian Palace or Fire Temple?

- ↑ Schapur II. On the lion hunt ( memento of the original from 23 August 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Soldier on wall painting from Pendishkent in a strongly Sassanid-influenced style

- ↑ Excerpt from the mosaic ( Memento of the original from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.