LEN model

The LEN model (from the English Linear Exponential Normal Model ), also known as the SPREMANN model, is a model derived from economics and is based on the principal-agent theory . Using the model to be explained, as indicated by hidden action (hidden action) to welfare losses coming. It was first mentioned in the book "Agency Theory, Information and Incentives" by Günter Bamberg and Klaus Spremann .

The model consists of two individuals, the agent and the principal. Both cooperate with the aim of maximizing their own benefit . The agent works for the principal and decides how much effort to put into his work for him. He is then paid for his work by the principal. The central problem the LEN model deals with is the hidden action problem, which prevents the principal from observing the agent's effort. Thus, the principal can only reward the agent based on the outcome of the work. The principal tries to use the form of remuneration to create incentives for the agent to work hard. It is believed that the hidden action problem prevents agent and principal from working out an effort-based employment contract.

Objective of the model

The agent in the LEN model is risk averse . He would rather receive a fixed, lower wage than a wage whose expected value is greater, but fraught with risk . So this wage can be higher or lower. He also has alternatives to working with the principal if he chooses not to work with him. These can be seen as job offers from other people. With these alternative options, he also receives a wage. The best of these options makes him a fortune . is described as the reservation value of the agent. The result achieved is not only influenced by the agent's work, but also by an interference term with the variance .

The risk aversion, the reservation value and the variance of the disturbance term are assumed to be exogenous variables. They are determined by the assumptions of the model and are taken as given. Endogenous variables are the agent's effort and the variables that describe the reward scheme. These variables are determined by the model. The aim of the model is to show how the agent chooses his effort and the principal chooses the remuneration scheme, taking into account the exogenous variables.

Structure of the model

Exertion and suffering from work

A basic assumption for the model is the difference in the desired effort that the agent should choose. This is referred to below as the effort level. The principal wants a high level of effort, while the agent prefers a low level of effort.

The higher the effort, the less the agent wants to work. He is burdened with the effort, which diminishes his usefulness. This so-called work suffering is a function that depends on the level of exertion . It can be interpreted as the cost of his effort and expressed in monetary terms:

The agent's suffering from work increases disproportionately with increasing effort, since the function is squared.

In order to choose the higher level of effort preferred by the principal, the agent must be compensated accordingly for the suffering caused by work. Thus both make an agreement in which the agent commits to a certain decision and the principal commits to a compensation payment.

The agent's net wage for his work is thus the principal's remuneration minus the work suffering:

is the wage depending on the result

is the result of the agent's work and is dependent on the effort and the disturbance term

are the function of the cost through the effort, the work suffering

Use

The benefit of the two actors is shown in the form of a benefit function . This shows how much benefit each monetary unit brings to the individual actor. The agent's benefit depends on his net wage. It rises through the payment of the principal and falls in the suffering of work. The principal wants the agent to make an effort. The more the agent tries, the greater the benefit from the collaboration. Likewise, the principal wants to keep as much money as possible for himself. As a result, the more wages he pays the agent, the less his utility is.

LEN assumptions

The name LEN model is derived from the assumption combination of linearity assumption , exponential assumption and normal distribution assumption .

Linearity assumption

The linearity assumption relates primarily to the remuneration scheme for the agent, but often also to the production function of the agent's work and the utility function of the principal.

Production function of the agent

The agent's production function represents his work. It leads to the result :

corresponds to a stochastic disturbance term and is a random variable . The disturbance term describes exogenous random influences on the production result . In this case, exogenous random influences can be, for example, luck or the behavior of a competitor in the market, which influences one's own production result. can alternatively be understood as a measurement error if the principal wants to determine the result .

is the result of the agent's work that, in the end, both the agent and the principal can observe. This is where the hidden action problem becomes clear, since the principal can only observe the result. He knows how the production function is structured and how and how it affects the result. However, the principal cannot find out how this result came about because he can neither observe nor observe. If is large and thus the result can be interpreted as successful, the principal does not know whether this is due to a high level of work on the part of the agent or to luck due to a high level of interference. The same applies vice versa: if the result is small, the principal doesn't know whether the agent was lazy or just unlucky.

Since the principal can observe the result , it is also contractible. This means that he can conclude a contract with the agent that is based on the result. This contract is designed in the form of a results-based remuneration scheme.

Linear remuneration scheme

The remuneration scheme is called linear because it has a linear structure. The agent's remuneration for his work is divided into two parts. A basic salary that is independent of success and a salary that is dependent on success . The performance-related fee can be understood as a commission . They are intended to create an incentive for the agent to choose the level of effort preferred by the principal. If he tries harder , his wealth will increase as a result and also because of the success- related wage .

The linear remuneration scheme is as follows:

- describes the total wages that the agent receives from the principal for his work

- is a parameter that determines how high the agent's commission is on the overall result achieved . Thus is and is called participation parameter

- is the non-performance-related basic wage and is called fixed wage

Utility function of the principal

The utility of the two individuals is described using utility functions. The principal's utility function represents the difference between the result of the agent's work and the wages that the principal must pay the agent:

Due to the linear utility function, the principal is risk-neutral .

Exponential assumption

The exponential assumption concerns the utility function of the agent. The utility function is characterized by constant absolute risk aversion (CARA). This means that his level of risk aversion does not change as his wealth increases or decreases:

- describes the agent's assets in monetary units, i.e. his wages minus work suffering:

- is the constant Arrow-Pratt measure of risk aversion. It describes how great the agent's risk aversion is. It is the same at every point in the function.

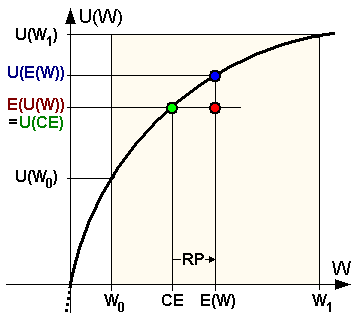

The net wage is fraught with risk or uncertainty, as it depends on the production result , which in turn is influenced by. Because of his risk aversion, which is given by his utility function, the agent prefers to receive a fixed wage rather than a result-related one. The agent's benefits can be described in terms of the security equivalent.

The security equivalent describes that secure amount of money for which the agent is indifferent between the risky payment and the security equivalent. Thus the amount of the security equivalent is worth to the agent as much as an amount that can be higher or lower. Since the agent is risk averse, the safety equivalent is below the expected value of the reward . The agent would rather receive a lower, secure amount than a result-dependent and thus risky amount, the expected value of which, however, is higher.

Normal distribution assumption

The normal distribution assumption relates to the disturbance term (also called error term) in the agent's production function. The result achieved by the agent is not only dependent on his effort, but also on an exogenous error term that can be interpreted as luck. is a random variable that is normally distributed with the expected value and the variance . This means that the positive and negative random influences on average balance each other out again. can be seen as a measure of the exogenous risk associated with production. The larger, the more the result can deviate from the effort. The principal does not know what size the error term is. He only knows the normal distribution of the error term. Thus, he is unable to deduce the agent's effort from the end result. Neither the principal nor the agent have any influence on the disturbance term.

Process of the model

Individual steps in the model

The LEN model consists of 4 steps:

- First, the principal creates a compensation scheme and presents it to the agent. In doing so, he determines the fixed salary that is independent of success and the participation parameters .

- In the second step, it is the agent's turn and decides whether or not to approve the remuneration scheme. The alternatives to working for the principal offer him the reservation value . Thus, he only accepts the offer of the principal if his benefit from the cooperation with him is at least as great as .

- When the agent has decided to accept the contract, he decides how much effort to invest in the work. He chooses the level of exertion .

- Then the natural state is realized and the result comes about. Both the agent and the principal are watching. On the basis of the result, the payment can be made to the agent and the cooperation between the two ends.

Choice of remuneration scheme

The principal will design the remuneration scheme in such a way that his own benefit is maximized. This is the result achieved minus the wages paid to the agent . Although the principal cannot observe which effort the agent chooses, he knows all of its important properties. Thus, he can anticipate the agent's decision. The principal knows:

- The agent's utility function

- The function of work suffering

- The efforts the agent can choose between

- The agent's reservation value

With this knowledge, the principal can determine whether or not the agent will accept a proposed contract. The principal's goal is to keep as much of the result as possible to himself so that his own benefit is maximized. He takes into account that the payment to the agent is at least as large as his reservation value . A reward scheme that brings the agent less assets than the reservation value would be rejected by the agent . As soon as it makes him more fortune, he'll take it. It is therefore assumed that the principal proposes a compensation scheme that brings in the same amount of wealth as the agent . The assumption is that the agent will just about accept this compensation scheme. He then receives a wage equal to the value of his reservation.

The security equivalent brings the agent as much benefit as the risky payout. Therefore, the safety equivalent can be used to represent the benefit from the remuneration. In the CARA case, it is calculated as the difference between the expected value and the risk premium . The risk premium is subtracted from the expected value .

The security equivalent is therefore:

is the non-performance-related fixed wage and the share in the result . is thus the performance-related part of the remuneration. With , the agent only receives a fixed salary that is independent of the result achieved. If the agent bears the full risk of the outcome. The fixed wage can also be negative. In this case, it is an upfront payment that the agent makes to the principal. The agent then pays to participate in the cooperation. He would do this if the cooperation is promising and he gets at least the reservation value. The principal finds the remuneration scheme that maximizes benefits for himself by anticipating the agent's reaction to the remuneration scheme proposed by him.

Reaction of the agent to the compensation scheme

The agent's assets are described by:

His wealth is to be equated with the security equivalent:

Explanation: because the variance of and

The agent wants to choose so that their assets are maximized. Thus he establishes the condition of the first order according to (according to derive):

- leads to

The optimal use is the agent's reaction to the compensation scheme chosen by the principal. Optimal use shows that neither the fixed wage nor the reservation value have an impact on the agent's efforts . A pay scheme that would consist of a fixed wage only encourages the agent to make the lowest possible effort , no matter how high the fixed wage is.

With the optimal effort of the agent, the following results for his assets (by using his asset function):

The agent agrees to the cooperation if his assets are at least as large as the reservation benefit . The principal maximizes its utility by keeping labor costs as low as possible. Then as much as possible is left for him. He therefore selects the parameters and in such a way that the agent's assets correspond exactly to his reservation benefits.

The following results for the agent's assets:

after reshaped:

In the upper of the two equations it can be seen that and are mutually substitutable. If the fixed wage gets smaller, it has to increase so that the expression continues to be .

Increasing the participation parameter results in three effects:

- Wealth effect : increases , the expected wage payment to the agent also increases. His expected wealth is thereby increased.

- Incentive Effect : A higher stake causes the agent to choose a higher stake . Thereby he attains a higher fortune for himself.

- Risk effect : A higher risk increases the agent's assets. As a result, they need a higher risk premium. The risk premium is the difference between the security equivalent and the expected wealth.

The equation of shows that the substitutability of and is no longer given if the risk effect is too great, i.e. if . Then the expression in brackets would be negative and the agent's risk aversion too great. In this case, the risk effect dominates over the wealth effect. So if you increase, you also need to increase so that the left part of the equation is at least as large as . This can be seen as compensation for the risk taken.

Maximize the principal's assets

The principal chooses the parameters and so that his utility is maximized. Its benefits are given by:

- .

There is

The principal is risk-neutral, so his benefit corresponds to the expected benefit:

Taking into account the chosen use of the agent , the principal wants to maximize his benefit. For results:

( And in use)

The principal chooses the best possible in order to maximize his own benefit. The utility is maximized by setting the first order condition (after deriving):

- leads to

The optimal fixed wage can be calculated with the help of :

With and the parameters for the remuneration scheme are set. The principal presents the compensation scheme to the agent. The latter accepts it because it provides him with the same benefit as his reservation value . The agent now selects the optimal effort in relation to the proposed values and :

- This also results in :

The agent's benefit in paying wages is just as great as his benefit from it . The benefits of the principal are :

, and are inversely dependent on what makes the contradiction between incentive design (participation in profit through ) and risk sharing clear. It is better for the principal to reduce the success-dependent part if the risk aversion of the agent and / or the variance of the disturbance term increases. With greater risk aversion and variance of the disturbance term, the agent needs a higher risk premium in order to be compensated for the risk incurred. However, the agent never only receives a performance-based remuneration, no matter how great his risk aversion is.

The principal tries to keep his own assets as risk-free as possible ( almost 1), if or are small. Through the incentive effect, the principal can induce the agent to make a great effort , since the required risk premium is low.

Since the expected benefit of the principal increases and decreases, the principal prefers agents with a low reservation value , a low degree of risk aversion (small ) and a production function with the smallest possible variance.

Agency costs

The agency costs in the LEN model are the loss of welfare that arises from the fact that the cooperation arises under the assumption of incomplete information. If complete information were given, the principal could observe the agent's work and pay directly. A success-related remuneration scheme with incentives for effort would then not be necessary. The costs can be determined because the agent's wages correspond to the reservation value, both with complete and incomplete information. Thus, in both situations there is only one difference in the expected utility of the principal. The agency costs are the difference in the benefit of the principal with complete information and with hidden action . They can be seen as the value of perfect information, that is, how much the principal would be willing to pay in order to observe the agent's chosen effort.

Since the full information is now a success-independent remuneration scheme, the principal only has to consider the reservation value and the agent's suffering. So he only compensates the agent for his work suffering and forgoing the alternative option.

The agent's fortune would then be:, and his wages

The expected benefits of the principal are:

Now the principal seeks the level of effort that maximizes benefits for him . This is determined by the first order condition (after deriving):

- leads to

The expected benefits of having the principal are:

The agency costs are then:

These are independent of the reservation value and the agent's assets. You get in . As a result, the costs incurred due to incomplete information and thus the actual problem of hidden action are greater, the greater the risk aversion of the agent and the variance of the disturbance term.

application

The LEN model is used in finance as well as in the theory of wages . The aim is to demonstrate the conflict of objectives between the design of incentives and efficient risk distribution between the actors.

In finance, it models the collaboration between an entrepreneur (agent) and a financier (principal). The aim is to find the optimal risk distribution for a company between the two actors. The design of the remuneration scheme is intended to harmonize the interests of the principal and agent and thereby provide a solution to the moral hazard problem .

In human resources , the model is used to analyze incentive systems. A contractual relationship between the owners of a company (principal) and a manager (agent) is shown here.

See also

Individual evidence

- ^ Lambert, Richard A.: Contracting theory and accounting. Ed .: Journal of accounting and economics. tape 32 , no. 1 , p. 3-87 .

- ^ Matthias Kräkel: Organization and Management. 5th edition. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2012, pp. 69–71, ISBN 978-3-16-151977-2

- ^ Christiane E. Bannier: Contract theory. An introduction with financial economic examples and applications. Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag, 2005, pp. 82-86, ISBN 3-7908-1573-X

- ^ Wolfgang Burr, Michael Stephan, Clemens Werkmeister: Management. 2nd Edition. Munich: Franz Vahlen, 2011, pp. 284–285, ISBN 978-3-8006-3829-1

literature

- Klaus Spremann: Agent and Principal. In: Günter Bamberg, Klaus Spremann (eds): Agency Theory, Information and Incentives. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1987, pp. 3-37, ISBN 3-540-18422-8

- Matthias Kräkel: Organization and Management. 5th edition. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2012, pp. 34–43 & pp. 69–71, ISBN 978-3-16-151977-2

- Bernd Rudolph: Corporate Finance and Capital Market. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2006, pp. 196–204, ISBN 3-16-147362-0

- Klaus Spremann: Profit-Sharing Arrangements in a Team and the Cost of Information. Taiwan Economic Review 16 (March 1988) 1, pp. 41-57.

- Wolfgang Burr, Michael Stephan, Clemens Werkmeister: Management. 2nd Edition. Munich: Franz Vahlen, 2011, pp. 284–288, ISBN 978-3-8006-3829-1

- Werner Neus, Jürgen Eichberger: Introduction to business administration. 8th edition. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2012, pp. 186-192, ISBN 978-3-16-152747-0

![s \ in [0.1]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/aff1a54fbbee4a2677039524a5139e952fa86eb9)

![{\ displaystyle E [\ theta] = 0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/045baa361f2d268e9230e0eb7f3a05b3dff46e52)

![{\ displaystyle CE = E [x] - {\ frac {1} {2}} \ alpha \ sigma ^ {2} = r + sx ^ {2} - {\ frac {1} {2}} \ alpha \ sigma ^ {2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7b7e3cc2e231cba409e5cdfa41de1777f42a5769)

![{\ displaystyle w = E [w] - {\ frac {1} {2}} \ alpha Var (w) = r + sx-x ^ {2} - {\ frac {1} {2}} \ alpha s ^ {2} \ sigma ^ {2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/aafdc934d9e47545fa7da9dedb6c44591a01bdd9)

![{\ displaystyle]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/604326beb4b48cc622f2e386be688a2c3a8bf86a)

![{\ displaystyle V = E [V] = (1-s) xr}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/443cf72a8986eab9e21b2803739570f3d5f9c64a)

![{\ displaystyle E [V]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/69437cc2542b3ef18fe18cdf32cdd8ef4a4b9091)

![{\ displaystyle E [V] = E [f] -r = xmx ^ {2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0e8f0b9664c9e1a178db43693e3794cf5c3065d7)

![{\ displaystyle {\ frac {\ partial E [V]} {\ partial x}} = 0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5d20686f8365dfa346717478166c72587bffc0e4)

![{\ displaystyle \ textstyle E [V] = {\ frac {1} {4}} - m}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fd497bf89978f0baa94dce1e36dd5818a7d444c3)

![{\ displaystyle \ textstyle agency costs = E [V | {\ mbox {perfect information}}] - E [V | {\ mbox {imperfect information}}] = {\ frac {\ alpha \ sigma ^ {2}} {4 \ alpha \ sigma ^ {2} +2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/993ada6f46d62eac3c7f48ccb92907926fc5fe9c)