Maillotins uprising

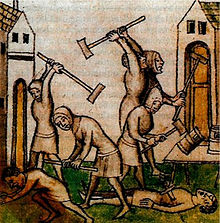

The Maillotins revolt was directed against tax practices in France in the 14th century . It broke out in Paris on March 1, 1382 and ended on March 10. The uprising got its name from the lead mallets ( Maillets de plomb ) with which the angry crowd stormed the Hôtel de Ville . The insurgents were called les Maillets , from which les Maillotins developed.

Causes and course

Since the 1340s, tax policy had proven problematic. The grievances could not be remedied either by the Estates General of 1356 or by the suppression of the Jacquerie (1358). Especially towards the end of his reign, Charles V (1338–1380) pursued reform policies, so it was no surprise when he banned fouage on his deathbed in 1380 . It was a household taxation.

After the death of Charles V, the people expected that his successor Charles VI. (1368–1422) who would hire Aides (literally 'help'). These were taxes that had been levied on various goods and means of transport in the Généralités , the capitals of the historical provinces, in order to collect the ransom for John II (1319-1364). Johann was taken prisoner in 1356. Although he had died in 1364, the aides , which were actually limited to six years, had not been hired. The uncles of twelve-year-old Karl VI. exercised rule for him during the reign of the dukes (1380-1388). They raised taxes and riots broke out in the Généralités. In 1379 the cities of Languedoc rebelled . When the Estates General decided in February 1381 to reintroduce the Fouages , the cities of Languedoc rebelled again. On February 24, 1382, the inhabitants of Rouen in Normandy rebelled after an aide and the salt tax had been increased. On March 1, 1382, Paris and various other cities rebelled.

The insurgents looted the town hall and various townhouses of wealthy citizens. The notables were in a difficult position between the rebels and the government negotiator, Enguerrand VII. De Coucy (1339-1397). The Prévôt des marchands had therefore fled. In the end, the notables paid the negotiator a sum of 80,000-100,000 francs , thereby ending the uprising.

The Parisians were punished only from January 11, 1383, when the king and his uncles moved into the city with their army. Urban freedoms were restricted by decree on January 27th. The Prévôt des marchands was not banned, but all civil associations and assemblies were banned, which meant that no new Prévôt des marchands could be elected. Several people were executed, often of an advanced age and not involved in the uprising. This included Jean Desmarets (also known as Jean Des Marès), the Advocate General of the Parliament of Paris. He had been an adviser to Charles V.

It took the skill of the Garde de la Prévôté des marchands Jean Jouvenel , who was appointed in 1389, to gradually regain the privileges of the Parisians. The Prévôté des marchands was restored in 1412 under the rule of the Bourguignons .

See also

literature

- Paul Robiquet (1848–1928): Histoire municipale de Paris depuis les origines jusqu'à l'avènement de Henri III . C. Reinwald, Paris 1880, IV, p. 109-148 (French, online ).

- Léon Mirot: Les insurrections urbaines au début du règne de Charles VI (1380–1383): leurs causes, leurs conséquences . Fontemoing, 1905 (French, online ).

- Patrick Boucheron, Société des historiens médiévistes de l'enseignement supérieur public (ed.): Les villes capitales au moyen age: XXXVIe congrès de la SHMES, Istanbul, 1er-6 June 2005 . Publications de la Sorbonne, 2006, ISBN 2-85944-562-5 , pp. 143–147 (French, limited preview in Google Book search).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Patrick Boucheron, Société des historiens médiévistes de l'enseignement supérieur public (ed.): Les villes capitales au moyen age: XXXVIe congrès de la SHMES, Istanbul, 1er-6 June 2005 . Publications de la Sorbonne, 2006, ISBN 2-85944-562-5 , pp. 144 (French, limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Paul Robiquet (1848–1928): Histoire municipale de Paris depuis les origines jusqu'à l'avènement de Henri III . C. Reinwald, Paris 1880, IV, p. 133 (French, online ).

- ↑ Léon Mirot: Les insurrections urbaines au début du règne de Charles VI (1380-1383): leurs causes, leurs conséquences . Fontemoing, 1905, p. 5 f . (French, online ).

- ↑ Léon Mirot: Les insurrections urbaines au début du règne de Charles VI (1380-1383): leurs causes, leurs conséquences . Fontemoing, 1905, p. 7 (French, online ). and Paul Robiquet (1848-1928): Histoire municipale de Paris depuis les origines jusqu'à l'avènement de Henri III . C. Reinwald, Paris 1880, IV, p. 112 f . (French, online ).

- ^ Paul Robiquet (1848-1928): Histoire municipale de Paris depuis les origines jusqu'à l'avènement de Henri III . C. Reinwald, Paris 1880, IV, p. 126 (French, online ).

- ↑ Patrick Boucheron, Société des historiens médiévistes de l'enseignement supérieur public (ed.): Les villes capitales au moyen age: XXXVIe congrès de la SHMES, Istanbul, 1er-6 June 2005 . Publications de la Sorbonne, 2006, ISBN 2-85944-562-5 , pp. 143 (French, limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Paul Robiquet (1848-1928): Histoire municipale de Paris depuis les origines jusqu'à l'avènement de Henri III . C. Reinwald, Paris 1880, IV, p. 137 (French, online ).

- ↑ Patrick Boucheron, Société des historiens médiévistes de l'enseignement supérieur public (ed.): Les villes capitales au moyen age: XXXVIe congrès de la SHMES, Istanbul, 1er-6 June 2005 . Publications de la Sorbonne, 2006, ISBN 2-85944-562-5 , pp. 145 f . (French, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Paul Robiquet (1848-1928): Histoire municipale de Paris depuis les origines jusqu'à l'avènement de Henri III . C. Reinwald, Paris 1880, IV, p. 154 (French, online ).

- ↑ Boucheron is invited to be a member of the delegation for the "guest country France" as a representative at the 2017 Frankfurt Book Fair