Declaration of Independence from Mecklenburg

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence is said to be the first declaration of independence to be made in the Thirteen Colonies during the American War of Independence . It was reportedly signed by a Mecklenburg County Citizens Committee on May 20, 1775 in Charlotte , North Carolina . After learning of the Battle of Lexington , the citizens declared their independence from the British Crown . Assuming that the Mecklenburg Declaration existed, it would have been the first United States Declaration of Independence and a year before the United States Declaration of Independence . The authenticity of the Mecklenburg Declaration has been disputed since it was first published in 1819, 44 years after it was supposedly written. There is no concrete evidence for the existence of the document and no reactions in the contemporary press of 1775 suggesting such a declaration.

history

Many historians assume that the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence is a flawed transmission of an actual document known as Mecklenburg Resolves . The Mecklenburg Resolves, signed on May 31, 1775, were a series of radical resolutions that came very close to an actual declaration of independence. Although published in the magazines of 1775, the text of the Mecklenburg Resolves was lost after the American Revolution and was not rediscovered until 1838. Historians assume that the Mecklenburg Declaration was written around 1800 and represents an attempt to reconstruct the text of the Mecklenburg Resolves from memory. According to this theory, the author of the Mecklenburg Declaration mistakenly believed that the Resolves were an actual declaration of independence and wrote his postscript in a language that was also used in the creation of the American Declaration of Independence. Those who believe in the authenticity of the Mecklenburg Declaration assume that both documents are authentic.

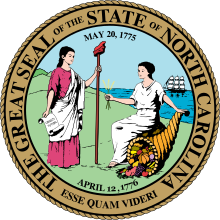

A previous North Carolina government believed in the Mecklenburg Declaration and insisted that the North Carolinians were the first Americans to declare their independence from the British. As a result of this belief, both the flag and seal of North Carolina remind of the event with the date of the declaration. May 20, "Meck Dec Day" is considered a public holiday in North Carolina, even if it is not counted as part of the official state holiday and no longer receives the same attention as in earlier times.

First publication

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence was first published by Joseph McKnitt Alexander in the Raleigh Register and North Carolina Gazette on April 30, 1819 im. In the foreword to the article, the newspaper's editor wrote, "Not many of our readers are likely to know that the citizens of Mecklenburg County declared their independence a year before the Congressional Declaration of Independence."

According to Alexander, his father, John McKnitt Alexander, was the secretary for a meeting in Charlotte on May 19, 1775. Each division of the Mecklenburg County militia had two representatives sent to the meeting. It was intended to discuss how to deal with the ongoing conflict between the British Empire and the Thirteen Colonies. The tensions between the colonies and the British Crown had with the Boston Tea Party reached in December 1773 a climax of the 1774 by the British Parliament adopted Intolerable Acts (Engl. For Unbearable laws ) was followed. During that meeting in Mecklenburg County, news of the Battle of Lexington, which had taken place in Massachusetts a month earlier, came in . Beside themselves with indignation, according to Alexander, the delegates passed the following resolutions at around 2 a.m. on May 20th:

- Resolved, That whosoever directly or indirectly abetted, or in any way, form, or manner, countenanced the uncharted and dangerous invasion of our rights, as claimed by Great Britain, is an enemy to this County, to America, and to the inherent and inalienable rights of man.

- Resolved, That we the citizens of Mecklenburg County, do hereby dissolve the political bands which have connected us to the Mother Country, and hereby absolve ourselves from all allegiance to the British Crown, and abjure all political connection, contract, or association, with that Nation, who have only trampled on our rights and liberties and inhumanly shed the innocent blood of American patriots at Lexington.

- Resolved, That we do hereby declare ourselves a free and independent people, are, and of right ought to be, a sovereign and self-governing Association, under the control of no power other than that of our God and the General Government of the Congress ; to the maintenance of which independence, we solemnly pledge to each other, our mutual cooperation, our lives, our fortunes, and our most sacred honor.

- Resolved, That as we now acknowledge the existence and control of no law or legal officer, civil or military, within this County, we do hereby ordain and adopt, as a rule of life, all, each and every of our former laws - where , nevertheless, the Crown of Great Britain never can be considered as holding rights, privileges, immunities, or authority therein.

- Resolved, That it is also further decreed, that all, each and every military officer in this County, is hereby reinstated to his former command and authority, he acting conformably to these regulations, and that every member present of this delegation shall henceforth be a civil officer, viz. a Justice of the Peace, in the character of a 'Committee-man,' to issue process, hear and determine all matters of controversy, according to said adopted laws, and to preserve peace, and union, and harmony, in said County, and to use every exertion to spread the love of country and fire of freedom throughout America, until a more general and organized government be established in this province.

According to Alexander's article, Captain James Jack from Charlotte was dispatched to the Continental Congress a few days later with a copy of the declaration . He also carried a letter to North Carolina Congressmen asking them to ratify the resolutions by Congress. North Carolina MPs, including Richard Caswell , William Hooper and Joseph Hewes, supported the resolutions, but informed Jack that it would be premature to debate a Declaration of Independence in Congress.

Although the original documents were destroyed in a fire in 1800, according to Alexander, he stated that he had transferred the resolutions from a faithful copy left by his late father.

Jefferson's doubts

" Either these resolutions are a plagiarism from Mr. Jefferson's Declaration of Independence, or Mr. Jefferson's Declaration of Independence is a plagiarism from those resolutions. "

The 1819 article on the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence was published in many other newspapers in the United States. Although the Mecklenburg Declaration was supposedly drafted a year before the American Declaration of Independence, which appeared in 1776, readers immediately recognized that the two declarations contained very similar phrases. The formulations: “dissolve the political bands which have connected”, “absolve ourselves from all allegiance to the British Crown” “are, and of right ought to be” and “pledge to each other, our mutual cooperation, our lives” were particularly striking "Our fortunes, and our most sacred honor". The obvious question was about the origin of the American Declaration of Independence: Did Thomas Jefferson , the authoritative author of the American Declaration of Independence, use the Mecklenburg Declaration as a source?

John Adams , like Jefferson, already retired when the Mecklenburg Declaration was published in 1819, believed in the authenticity of the declaration. When he saw Alexander's article in a Massachusetts newspaper, he was amazed that he had never heard of such a statement before. According to a letter he sent to a friend, he believed that Jefferson had incorporated the spirit, meaning, and expressions of the Declaration verbatim in the Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776. Adams, who played an important role in convincing the Continental Congress to make a declaration of independence, resented Jefferson for getting most of the fame for the declaration, despite copying it from a later rediscovered document. He is said to have been happy about the reappearance of the Mecklenburg Declaration in a private setting, as it undermined Jefferson's claim to originality and his primacy. He sent a copy of the article to Jefferson to see how Jefferson reacted to it.

Jefferson replied that, like Adams, he had no knowledge of the document. He found it strange that the historians of the American Revolution hadn't mentioned this statement, nor had the historians from North Carolina and nearby Virginia ever mentioned it. It seemed suspicious to him that the originals were destroyed in a fire and that most of the eyewitnesses had already died. Jefferson wrote that he could prove neither the existence nor the nonexistence of the document and therefore assumed a forgery until clear evidence was given.

Adams wrote in his reply to Jefferson's letter that his arguments had completely convinced him that the Mecklenburg Declaration was fabricated. Adams forwarded Jefferson's letter to the editor of a newspaper in Massachusetts, who published these doubts about the Mecklenburg Declaration, but without mentioning Adams or Jefferson by name. In response to the expressed skepticism, North Carolina's Senator Nathaniel Macon and others gathered eyewitness accounts of the event described in Alexander's article. The now aged witnesses did not agree in every detail in their statements, but overall they confirmed that the Mecklenburg Declaration had been read out publicly in Charlotte, but were no longer sure about the date. The most important statement came from the then 88-year-old Captain James Jack, who confirmed that he had brought the Declaration of Independence, written in May 1775, to the Continental Congress. This provided the necessary proof for the existence of the Mecklenburg Declaration for many.

Alleged signatories

After the Mecklenburg Declaration was first published in 1819, supporters compiled a list of the men they believed had signed the declaration. William Polk , whose father Thomas Polk supposedly read the statement, added 15 names to the list who were among the delegates at the time. Other witnesses introduced other names. A pamphlet published by the North Carolina government in 1831 listed the names of 26 delegates who said they had signed the declaration:

- 1. Abraham Alexander

- 2. Adam Alexander

- 3. Charles Alexander

- 4. Ezra Alexander

- 5. Hezekiah Alexander

- 6. John McKnitt Alexander

- 7. Waightstill Avery

- 8. Rev. Hezekiah J. Balch

- 9. Richard Barry

- 10. Dr. Ephraim Brevard

- 11. Maj. John Davidson

- 12. Henry Downs

- 13. John Flenneken

- 14. John Foard

- 15. William Graham

- 16. James Harris

- 17. Richard (or Robert) Harris

- 18. Robert Irwin

- 19. William Kennon

- 20. Matthew McClure

- 21. Neil Morrison

- 22. Duncan Ochiltree

- 23. Benjamin Patton

- 24. John Phifer

- 25. Thomas Polk

- 26. John Queary

- 27. David Reese

- 28. Zacheus Wilson, Sr.

Later historians emphasized that the history of the signature in 1775 could in no way have originated before 1819. There is no contemporary source for such a signature, and John McKnitt Alexander never mentioned such an event in his records. As far as is known, none of those named as signatories has ever stated to have signed such a declaration. Like many of the early advocates of the Mecklenburg Declaration's authenticity, most of the alleged signers were Scottish-Irish Presbyterians . Many of the alleged signatories were related to one another, and their descendants were among the bitterest defenders of the declaration.

The eyewitnesses who testified about the 1775 congregation disagreed on the tasks each participant performed. John McKnitt Alexander said he was the meeting's secretary, but others recalled that Ephraim Brevard had made the record. Alexander wrote that his relative Adam Alexander had called the meeting, but William Polk and other eyewitnesses testified that the meeting was initiated by Thomas Polk. Abraham Alexander is said to have presided over the meeting.

Celebrations and controversies

In North Carolina and in the neighboring state of Tennessee , which emerged from the early colonial Carolina, people began to develop pride after 1819 in the previously unpublished Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. Previously, Virginia and Massachusetts had received the lion's share of the credit for leading the United States to independence from the British Crown. The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence clearly upgraded North Carolina's role for American independence, which was already above average due to the Halifax Resolves of April 1776. The first celebration of the anniversary of the assumed creation of the Mecklenburg Declaration took place in Charlotte on May 20, 1825.

Many North Carolinians felt assaulted and pride injured in the posthumous publication of Jefferson's letters in 1829. Not only had Jefferson, who came from Virginia, questioned the authenticity of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, he had also very undiplomatically referred to one of the signatories of the American Declaration of Independence from North Carolina, William Hooper, as " Tory ". Jefferson did not use the term to imply that Hooper was loyal to the British Crown, but wanted to express that Hooper had been conservative in his view of the Declaration of Independence, but the North Carolinians saw this as an affront to one of the patriots they adored .

The North Carolina government responded to Jefferson's letter in 1831 with an official statement listing previously published testimony and other unpublished eyewitness accounts in support of the credibility of the Mecklenburg Declaration. This pamphlet was followed by a book published in 1834 by one of North Carolina's leading historians Joseph Seawell Jones: A Defense of the Revolutionary History of the State of North Carolina from the Aspersions of Mr. Jefferson. Jones defended William Hooper's patriotic stance and accused Jefferson of being jealous of small Mecklenburg County that had declared independence at a time when Jefferson, the "sage of Monticello " was still hoping for an amicable settlement with the British. On May 20, 1835, more than 5000 people gathered in Charlotte to celebrate the Mecklenburg Declaration. Of the many toasts uttered in honor of the "first" declaration of American independence, Jefferson would not be mentioned again.

Jefferson's first biographer, George Tucker, took on the former president's defense in 1837. In his book, The Life of Thomas Jefferson , Tucker claimed that Jefferson's Declaration of Independence was fraudulently interpolated into the Mecklenburg Declaration . A North Carolina writer, Anglican clergyman Francis L. Hawks , who viewed Jefferson as an infidel, responded to this statement by claiming that Jefferson had plagiarized the Mecklenburg Declaration instead . Hawk's stance was evidently supported by the discovery of a proclamation by the last Royal Governor of North Carolina, Josiah Martin , which appeared to confirm the authenticity of the Mecklenburg Declaration. In August 1775, Governor Martin wrote that he had “seen the nefarious publication in the Cape Fear Mercury , resolutions written by a group of people who stylized themselves as the Mecklenburg County's committee for the treacherous dissolution of law, government and constitution declared, as well as issued a system of rules and regulations that run counter to the law and subversive against the government of the Crown. "

At last it seemed contemporary evidence of the radical resolutions passed in Mecklenburg County in 1775. However, the edition of the Cape Fear Mercury to which the governor was referring has not yet been found. Throughout the 19th century, the defenders of the Mecklenburg Declaration hoped that the missing edition would turn up and confirm its authenticity. In 1905, Collier's Magazine published a clipping of the missing newspaper, but both proponents and opponents agreed that it was a forgery. It was later confirmed that the "treacherous document" Martin was referring to was not the Mecklenburg Declaration, but the radical demands of the Mecklenburg Resolves.

Change of direction of the debate

The question of the authenticity of the Mecklenburg Declaration changed when the archivist Peter Force discovered an abbreviated list of resolutions passed in Mecklenburg on May 31, 1775 during his review of the newspapers from 1775 in 1838. These differed from the Mecklenburg Declaration of May 20 and were referred to as Mecklenburg Resolves. In 1847 the full text of these resolutions, published in June 1775 in a South Carolina newspaper, was finally rediscovered. In contrast to the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, which appeared in the Raleigh Register , the language of the Mecklenburg Resolves differed from the idioms used by Jefferson in the American Declaration of Independence, even if the resolutions themselves came very close to an actual declaration of independence. The Mecklenburg Resolves were similar to other, equally radical resolutions that were passed in the colonies in 1774 and 1775.

With this discovery, the debate about the authenticity of the Mecklenburg Declaration changed fundamentally. The focus of the discussion shifted from distrust of Jefferson to the question of how two such different documents could emerge in Charlotte in just 11 days. How was it possible that the citizens of Mecklenburg Counties declared their independence on May 20th and met again just a few days later on May 31st to take new and less radical decisions? For those who doubted the authenticity of the Mecklenburg Declaration, the answer was clear: The Declaration of Independence was an incorrectly dated and reproduced rewrite of the original Mecklenburg Resolves. The supporters of the Mecklenburg Declaration, however, assumed that these were two real documents that served different purposes.

Arguments against authenticity

The argument that the Mecklenburg Declaration was a flawed version of the Mecklenburg Resolves was first made in 1853 by Professor Charles Phillips, who worked at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill . taught. In a high-profile article in North Carolina University Magazine , Phillips suggested that John McKnitt Alexander had admitted to having recorded the text of the Mecklenburg Declaration from memory in 1800. In 1906 a scientific treatise by William Henry Hoyt was published, which in the eyes of contemporary historians conclusively demonstrated that the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence never existed. He argued that the original Mecklenburg Resolves documents were destroyed in a fire in 1800 and that John McKnitt Alexander tried to reconstruct them from his memory. For this purpose he made a few notes which are considered to have been made after the fire in 1800. Like many of his contemporaries, Alexander assumed that the radical Mecklenburg Resolves actually represented a declaration of independence. This assumption led Alexander or another unknown author to the decision to use the idioms from the well-known Jeffersonian Declaration when the Mecklenburg Declaration was modeled following the notes. The eleven days that lay between the two documents can be explained by the use of different times and the difference between the Gregorian and Julian calendars .

Following this argument, the witnesses, who were already aged at the time of the questioning, could of course no longer remember the individual words of the declaration that they had heard 50 years ago, nor could they remember the exact date of the public reading. Eyewitnesses were misled by the claim that the statement published in 1819 was a faithful copy of the original resolutions. After the decisions were very radical and the British authority in Mecklenburg was also ended in 1775, the witnesses believed that it had actually been a declaration of independence. The witnesses told the truth about their memory of May 1775 without any doubt, but the questions to the witnesses were asked suggestively and the answers matched the lost Mecklenburg Resolves. Unfortunately, by the time the resolutions were rediscovered, all of the eyewitnesses had died, so they could not be questioned about the existence of two different versions of the resolutions.

Arguments for authenticity

Proponents of the Mecklenburg Declaration argued that both the declaration and the resolutions were authentic. The argument formulated in the 20th century by Archibald Henderson. The professor at the University of North Carolina wrote a series of articles on the subject from 1916 onwards. He believed that the citizens of Mecklenburg Countys had passed two different resolutions, that the text of the Mecklenburg Declaration was not written from memory and that the events as they were described by Alexander in 1819 were in principle correctly portrayed. His work on this was summarized and published in 1960 by the journalist VV McNitt in the book Chain of Error and the Mecklenburg Declarations of Independence .

One of the strongest and almost contemporary evidence for the existence of the Mecklenburg Declaration is a diary entry that was discovered in 1904. The entry is unsigned nor dated, but there is evidence that the text, which was written in German in 1783 in Salem , North Carolina, came from a trader named Traugott Bagge. He wrote: “At the end of 1775 I cannot fail to mention that as early as the summer of that year, in May, June or July, Mecklenburg County in North Carolina declared itself free and independent from England and issued regulations to govern oneself, as the Continental Congress later did for everyone. The Congress, however, found this to be premature. "

Skeptics argue that the entry merely suggests that eight years after the events, Bagge misinterpreted the Mecklenburg Resolves as a declaration of independence. Henderson stated, however, that the diary entry proves both the declaration, in the wording "declared itself free and independent", as well as the resolutions with the expression "arrangements for the administration of the laws".

State of the debate

Today, the Mecklenburg Declaration hardly receives any attention from historians who generally consider the document to be false. If the declaration is mentioned in scientific works, it is usually only to question its authenticity. William S. Powell , who wrote the standard work North Carolina through Four Centuries in 1989 , only mentions the Mecklenburg Declaration in a footnote. Professor HG Jones put the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence in his work North Carolina Illustrated in ironic quotation marks. The Harvard Guide to American History from 1954 lists the Mecklenburg Declaration under the heading “False Declarations”.

Allan Nevins wrote:

“Legends often become a point of faith. At one time the State of North Carolina made it compulsory for the public schools to teach that Mecklenburg County had adopted a Declaration of Independence on May 20, 1775 - to teach what had been clearly demonstrated an untruth. "

“Legends often become a matter of belief. Once the state of North Carolina stipulated that the state schools had to teach that Mecklenburg County declared independence on May 20, 1775 - thereby teaching something that was clearly proven to be untruthful. "

In 1997 the historian Pauline Maier wrote:

“When compared to other documents of the time, the" Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence "supposedly adopted on May 20, 1775, is simply incredible. It makes the reaction of North Carolinians to Lexington and Concord more extreme than that of the Massachusetts people who received the blow. The resolutions of May 31, 1775, of which there is contemporary evidence, were also radical, but remain believable. "

“Compared to other documents from this period, the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, which was supposedly passed on May 20, 1775, is simply untrustworthy. It makes the North Carolinians' reaction to [the skirmishes of] Lexington and Concord more extreme than the Massachusetts people who took the actual blow. The resolutions of May 31, 1775, for which there is contemporary evidence, were also radical, but remain credible. "

Despite the predominantly scientific stance on the question of the authenticity of the Mecklenburg Declaration, the historian Dan L. Morrill says that belief in the document is still important for some citizens of North Carolina. He notes that the authenticity of the document could not be completely refuted.

Dan L. Morrill wrote:

“One thing remains to be seen. Nobody can conclusively prove that the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence is a fake. The dramatic events of May 19th and 20th could really have happened. Ultimately, it remains a matter of belief, not evidence. Either you believe it or you don't believe it. "

"Let's make one thing clear. One cannot demonstrate conclusively that the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence is a fake. The dramatic events of May nineteenth and May twentieth could have happened. Ultimately, it is a matter of faith, not proof. You believe it or you don't believe it. "

Commemoration

The early North Carolinian government was convinced of the authenticity of the Mecklenburg Declaration and claimed that the North Carolinians were the first Americans to break away from the British Crown. This resulted in the date being included in the seal and flag of the state. Coins commemorating the Mecklenburg Declaration were minted and the story of the events was recorded in the primary school's school books. A memorial commemorating those who signed the Declaration was unveiled on May 20, 1898, and a plaque was placed in the rotunda of the North Carolina State Capitol on May 20, 1912 . In 1881 the government of North Carolina declared May 20 an official holiday to commemorate the Mecklenburg declaration of independence. The day, also known as "Meck Dec Day", is no longer a public holiday and is hardly considered anymore.

Four Presidents visited Charlotte to take part in the Mecklenburg Day celebrations: William Howard Taft (1909), Woodrow Wilson (1916), Dwight D. Eisenhower (1954), and Gerald Ford (1975). Aware of the controversy surrounding the authenticity of the declaration, the presidents highlighted the revolutionary patriots from Mecklenburg County, but did not comment on the authenticity of the controversial document.

The motto of the Davidson College in Davidson in Mecklenburg and Iredell County refers to the Mecklenburg Declaration with the words "Alenda Lux Ubi Orta Libertas" ( Latin for knowledge there where freedom rose ).

literature

- Adelaide L. Fries: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence as Mentioned in the Records of Wachovia . Edwards & Broughton, Raleigh NC 1907 (English).

- George W. Graham: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, May 20, 1775, and Lives of Its Signers . Neale, New York NY 1905.

- William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence… is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York NY 1907 (English).

- Victor C. King: Lives and Times of the 27 Signers of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence of May 20, 1775. Pioneers extraordinary . sn, Charlotte NC 1956.

- Pauline Maier: American Scripture. Making the Declaration of Independence . Knopf, New York NY 1997, ISBN 0-679-45492-6 (English).

- James H. Moor: Defense of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. An Exhaustive Review of and Answer to All Attacks on the Declaration . Edwards & Broughton, Raleigh NC 1908.

- Dan L. Morrill: Historic Charlotte. An Illustrated History of Charlotte & Mecklenburg County. Historical Publishing Network, San Antonio TX 2001, ISBN 1-893619-20-6 .

- Merrill D. Peterson: The Jefferson Image in the American Mind . Oxford University Press, New York NY u. a. 1960, p. 126-128, 141 (English).

Historical treatises

- George W. Graham: Why North Carolinians Believe in the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence of May twentieth, 1775 . 2d edition revised and enlarged. Queen City Printing, Charlotte NC 1895.

- William Alexander Graham : The Address of the Hon. Wm. A. Graham on the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence […]. EJ Hale, New York NY 1875.

- Joseph Seawell Jones: A Defense of the Revolutionary History of the State of North Carolina. From the Aspersions of Mr. Jefferson. C. Bowen et al. a., Boston MA et al. a. 1834 ( Making of modern law ).

Essays and articles

- Archibald Henderson: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence . In: The Journal of American History . 1912 (English, online [accessed October 27, 2010]).

- Charles Phillips: May, 1775 . In: North Carolina University Magazine , May 1853. (unsigned)

- VV McNitt: Chain of Error and the Mecklenburg Declarations of Independence . Hampden Hills Press et al. a., New York NY u. a. 1960 (English, online [accessed October 27, 2010]).

- Alexander Samuel Salley Jr .: The Mecklenburg Declaration. The Present Status of the Question . In: The American Historical Review . Vol. 13, No. 1, October 1907, pp. 16-43.

- James C. Welling: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence . In: The North American Review 118, Issue 243, April 1874.

- Cradle of Liberty. Historical Essays Concerning the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, May 20, 1775 . Mecklenburg Historical Association, Charlotte NC 1955.

Web links

- Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County: "Celebrating the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence"

- May 20th Society

- Mecklenburg Historical Association

Individual evidence

- ^ Pauline Maier: American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. Knopf, New York 1997, ISBN 0-679-45492-6 , pp. 172-173 (English). ; Alexander's 1819 article was reprinted in William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence ... is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 3–7 (English).

- ^ A b c William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence ... is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 3–6 (English).

- ^ Pauline Maier: American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. Knopf, New York 1997, ISBN 0-679-45492-6 , pp. 172-173 (English). and William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence ... is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 3–7 (English).

- ↑ German translation: "Either these resolutions are a plagiarism of Jefferson's Declaration of Independence, or Jefferson's Declaration of Independence is a plagiarism of those resolutions" Original quote in John Adams, Charles Francis Adams: The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States . Little, Brown, Boston 1856, pp. 383 (English).

- ^ A b c William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence ... is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 7-12 (English).

- ↑ From the first sentence of the American Declaration of Independence, translated: "to dissolve the political ties that previously united it with another". The full translation is available from the United States Declaration of Independence given in Congress on July 4, 1776. Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of North America. In: Constitutions of the World. Retrieved May 10, 2009 (translation from 1849).

- ↑ From the last paragraph of the American Declaration of Independence, translated: "Freed from all obedience to the British Crown". The full translation is available from the United States Declaration of Independence given in Congress on July 4, 1776. Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of North America. In: Constitutions of the World. Retrieved May 10, 2009 (translation from 1849).

- ↑ From the last paragraph of the American Declaration of Independence, translated: "to be it, to have the right". The full translation is available from the United States Declaration of Independence given in Congress on July 4, 1776. Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of North America. In: Constitutions of the World. Retrieved May 10, 2009 (translation from 1849).

- ↑ From the last sentence of the American Declaration of Independence, translated: "With firm trust in the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually vouch for our lives, our property, and our inviolable honor". The full translation is available from the United States Declaration of Independence given in Congress on July 4, 1776. Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of North America. In: Constitutions of the World. Retrieved May 10, 2009 (translation from 1849).

- ^ A b Merrill D. Peterson: The Jefferson Image in the American Mind. Oxford University Press, New York 1960, pp. 140-141 (English).

- ^ A b Pauline Maier: American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. Knopf, New York 1997, ISBN 0-679-45492-6 , pp. 172-173 (English).

- ↑ "I shall believe it such until positive and solemn proof of its authenticity shall be produced." The correspondence between Adams and Jefferson pertaining to the Mecklenburg Declaration has often been reprinted. Extracts can be found, for example, in William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence… is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 7-11 (English). or DA Tompkins, History of Mecklenburg County and the City of Charlotte (1904), p. 14 .

- ^ "Has entirely convinced me that the Mecklengburg Resolutions are a fiction" William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence ... is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 11 (English).

- ↑ Captain Jack's testimony was often reprinted, for example in William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence… is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 251-252 (English).

- ^ A b William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence ... is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 12-14 (English).

- ^ A b William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence ... is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 218-219 (English).

- ↑ a b Richard M. Current: That Other Declaration: May 20, 1775 – May 20, 1975 . In: North Carolina Historical Review . No. 54 , 1977, pp. 169-191 (English).

- ↑ a b c d William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence… is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 15-17 (English).

- ^ A b Merrill D. Peterson: The Jefferson Image in the American Mind. Oxford University Press, New York 1960, pp. 142 (English).

- ^ Merrill D. Peterson: The Jefferson Image in the American Mind. Oxford University Press, New York 1960, pp. 126-128, 141 (English).

- ↑ Original quote in English: "seen a most infamous publication in the Cape Fear Mercury importing to be resolves of a set of people styling themselves a committee for the county of Mecklenburg, most traitorously declaring the entire dissolution of the laws, government, and constitution of this country, and setting up a system of rule and regulation repugnant to the laws and subversive of his majesty's government…. "

- ^ William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence ... is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 51-53 (English).

- ^ In Archibald Henderson: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence . In: The Journal of American History . 1912 (English, newrivernotes.com [accessed May 10, 2009]). Henderson noted that it was initially assumed that Martin had sent a copy of the Mecklenburg Declaration to England. In the meantime, however, it has been "established without any doubt" that it was a copy of the Resolves.

- ^ A b William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence ... is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 18-19 (English).

- ↑ VV McNitt: Chain of error and the Mecklenburg Declarations of Independence. Palmer, Massachusetts and New York: Hampden Hills Press, 1960, pp. 88 (English, cmstory.org [accessed May 10, 2009]). Chain of Error and the Mecklenburg Declarations of Independence. ( Memento of the original from December 4, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ A b William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence ... is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 28-30, 144, 150 (English).

- ^ William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence ... is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 141-142 (English).

- ^ William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence ... is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 171 (English).

- ^ William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence ... is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 29-30, 205-206 (English).

- ^ William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence ... is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 206 (English).

- ^ William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence ... is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 27 (English).

- ↑ VV McNitt: Chain of error and the Mecklenburg Declarations of Independence. Palmer, Massachusetts and New York: Hampden Hills Press, 1960 ( cmstory.org [accessed May 10, 2009]). Chain of Error and the Mecklenburg Declarations of Independence. ( Memento of the original from December 4, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Adelaide L. Fries: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence as Mentioned in the Records of Wachovia . Edwards & Broughton, Raleigh, North Carolina 1907, pp. 1–11 (English).

- ^ Translation from the English language: "I cannot leave unmentioned at the end of the 1775th year that already in the summer of this year, that is in May, June, or July, the County of Mecklenburg in North Carolina declared itself free and independent of England, and made such arrangements for the administration of the laws among themselves, as later the Continental Congress made for all. This Congress, however, considered these proceedings premature. "

- ^ A b William Henry Hoyt: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: A Study of Evidence Showing that the Alleged Early Declaration of Independence ... is Spurious . Knickerbocker Press, New York 1907, p. 119-120 (English).

- ^ A b Archibald Henderson: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence . In: The Journal of American History . 1912 (English, newrivernotes.com [accessed May 10, 2009]).

- ↑ Annotated in entry by Converse D. Clowse: Alexander, Abraham in American National Biography Online, February 2000

- ^ HG Jones: North Carolina Illustrated, 1524-1984 . University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1983, ISBN 0-8078-1567-5 (English).

- ^ Allan Nevins: The Gateway to History . D. Appleton-Century Company INC., New York, London 1938, pp. 119 (English).

- ^ Pauline Maier: American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. Knopf, New York 1997, ISBN 0-679-45492-6 , pp. 174 (English).

- ^ Dan L. Morrill: Independence and Revolution. Retrieved May 10, 2009 .

- ↑ VV McNitt: Chain of error and the Mecklenburg Declarations of Independence. Palmer, Massachusetts and New York: Hampden Hills Press, 1960, pp. 113–114 (English, cmstory.org [accessed May 10, 2009]). Chain of Error and the Mecklenburg Declarations of Independence. ( Memento of the original from December 4, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.