Molyneux problem

The Molyneux problem is a philosophical problem , first shown by William Molyneux in 1688 , which addresses the origin of human knowledge and the formation of concepts on the basis of blindness .

It is simplified as follows: Suppose a born blind man would receive the ability to see, he would be able cubes and spheres distinguished by the naked look at each other when it can be assumed that he cube and sphere already could distinguish his sense of touch ?

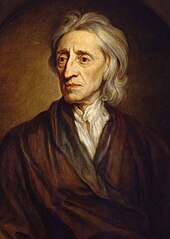

Attempts at solving philosophical problems have led to a discourse in the history of perception theory that is still widely recognized today . After the problem was published in John Locke's An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding in 1693 , this problem was discussed by many philosophers and scholars, such as George Berkeley , Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz , Voltaire , Denis Diderot , Julien Offray de La Mettrie , Hermann von Helmholtz and William James , who partly followed Locke's negative view.

The formulation of the problem by Molyneux

In a letter to John Locke on July 7, 1688, Molyneux said:

“Dublin, July 7th. 88

A problem posed to the author of the 'Essai Philosophique concernant L'Entendement humain'Suppose: an adult, born blind man who has learned to differentiate with his sense of touch between a cube and a ball made of the same metal and almost the same size, and who can tell when he has touched one or the other which of the cube and which is the ball. Suppose now that the dice and ball are placed on a table and the man has become sighted. The question is: whether he is able, through his sense of sight, before he has touched these objects, to distinguish them and tell which is the ball and which is the cube?

If the learned and ingenious author of the above treatise thinks this problem is worthy of attention and an answer, may he forward the answer at any time to someone who values him very much andHis most humble servant is.

William Molyneux

High Ormonds Gate in Dublin, Ireland "

John Locke did not reply to this letter. A little later, however, Locke took up this question, which Molyneux sent him again on March 2, 1692 (after they had become friends) in a similar form - but this time with a suggested answer - in the An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding in 1693. This led to a scientific discourse of contemporary philosophy in which neither side could unequivocally state their position. John Locke wrote:

“Imagine a man born blind who is grown up and has learned to differentiate between a cube and a sphere of the same metal and approximately the same size through his feeling, so that he can indicate whether he feels the sphere or the cube. Now suppose both are placed on a table and the blind man receives his face; Here the question arises whether, before he feels the balls, he can say which is the cube and which is the ball? The astute questioner says: No. The man knows from experience how a ball and a cube feel, but he does not yet know from experience whether what arouses his feeling one way or the other must also arouse his face in one way or another, and that a protruding corner in the cube, which his hand squeezed unevenly, must appear to his eye as it does with a cube. I agree with this astute gentleman, whom I am proud to call my friend, and believe that the blind man, at the first glance, will not be able to tell with certainty which is the sphere and which is the cube, if he also according to his feeling can designate them with certainty, and can distinguish their shapes with certainty according to this sense. "

With this paragraph about perception he referred directly to William Molyneux's statement and added an answer to the problem from Molyneux's point of view:

"No. The man knows from experience how a ball and a cube feel, but he does not yet know from experience whether what arouses his feeling one way or the other must also arouse his face in one way or another and that a protruding corner is in to the dice, which his hand squeezed unevenly, must appear to his eye as it happens with a dice. "

Historical approaches to problem solving

The discussion of the contemporary philosophy of the time concerned in particular the relationship between sight and the sense of touch and the corresponding question of whether the eye is physiologically able to perceive shapes or whether the perception of body and space is only "borrowed" from the sense of touch, i.e. the visual impression with the information previously acquired from the other senses can be linked. Since Molyneux died on October 11, 1698, he could no longer add to the discourse. There was agreement about the differences between visual and haptic sensory impressions, but not about the relationships between the various senses. The discourse was about whether the relationship between the various senses is learned through experience or whether there is a natural relationship between the various senses that arises automatically. Molyneux's question therefore deals with whether visual perception is separated from haptic perception and is only linked through experience, in which case the distinction between figures and figure naming would be impossible after the ability to see is achieved only on the basis of visual perception. Or the visual and haptic perception are based on the same concept and a connection takes place automatically, then the differentiation and naming of figures would be possible through visual perception alone. Molyneux and Locke argue that previous haptic experience is necessary in order to distinguish the objects, and that both forms cannot be correctly identified by optics alone. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Francis Hutcheson, on the other hand, were of the opinion that blind people are also able to understand geometry without visual representation, based on haptic form experience. This would be based on the similarity of the underlying idea of the sensory modalities vision and haptics. So they both answered in the affirmative to Molyneux's question. George Berkeley, on the other hand, agrees with Locke and Molyneux, but differentiates more precisely in that he postulates that seeing is a learning process and that those who now see who were previously blind would lack an experience concept with the new modality of seeing.

Empirical approaches to problem solving

Since Molyneux's problem looks at first sight like an empirically verifiable question, one should assume that today, more than three centuries later, a clear answer to the question can be given. However, even at the beginning of the 21st century, there is still no really comprehensive and general answer. In the meantime, studies have been carried out with people who have been blind since birth or childhood and whose eyesight was surgically restored, but the results of these studies are partly contradictory or inconclusive, even when working with control groups , i.e. some patients were explicitly assigned Molyneux's task was and others not. Some patients were able to carry out Molyneux's task - determining the figure - while others were not. The reliability and accuracy of some studies were also criticized. It is criticized that visual impressions immediately after an operation due to the status of the eye are not comparable with those of normal sighted people with lifelong visual experience. The severity of the sensory perception after a successful operation was also very different, so some patients could only differentiate between light and dark after the operation, others in turn colors and a few could perceive movement, distance and size. Another point of criticism of empirical studies on Molyneux's problem is the different ages at acquiring vision, which ranged from childhood to late adulthood.

The English doctor William Cheselden provided with his report on the first successful iridectomy in 1728 a medical-practical basis for the problem, which had been formulated in a speculative and philosophical way up to that point. Cheselden's patient was a thirteen-year-old boy who had lost sight so early that he had no memory of visual impressions. Cheselden's study of the boy's experience has been commented on by Berkeley, Thomas Reid , Voltaire, and others. Some, including Berkeley and the mathematician and theologian Robert Smith (1689–1768), invoked Cheselden's study in support of their own negative answer to Molyneux's question. Others, however, questioned the relevance of Cheselden's study, as the boy was initially unable to distinguish between figures. Cheselden wrote when the boy first saw, "he did not know the shape of anything, and could not distinguish objects, no matter how different in shape." Cheselden's study seemed to confirm Locke and Molyneux's suggestion that the recognition of objects is not part of the basic content of optical perception, but objects are only recognized when the corresponding haptic experience has been made and is then combined with optical perception.

Modern approaches to problem solving

The discussion of the Molyneux problem remained in the scientific discussion into the 21st century, but fell into the background among ophthalmologists, psychologists and neurophysiologists and was seen primarily as a philosophical debate of the Enlightenment. A current interim status of the solution to the Molyneux problem from the perspective of the 21st century predominantly confirms Locke and Molyneux's negation, but with a different justification. In particular, the gain in knowledge, highlighted by Locke, through the experience of the collaboration between vision and haptics, is now given little relevance. Rather, the entire perceptual process is organized in an innate scheme and is improved through a constant learning process. In this learning process, experiences and perceptions of one sense can influence those of the other.

Since the turn of the millennium, the interest of research, especially due to the far-reaching technological developments in the microchip and neurochip area , has increasingly focused on the parallel use of different sensory perceptions, the so-called multimodal perception, and the processing of information and the replacement of one sensory perception by another, so z. B. in the research area of human echolocation . It is similar to echolocation as used by bats and dolphins , whereby a trained person can interpret the reflected sounds of nearby objects and thus determine their location and, in part, their size.

Experimental solution to the problem

In 2011, five children who were blind from birth and who had been able to see for the first time after an operation between the ages of eight and seventeen were examined in a similar experimental setup.

Before the operation, the children felt similar building block figures and learned to distinguish them. After the operation, they were only given the objects they had previously felt to look at. At first they could not assign what they saw to what they felt, but learned this very quickly in the further course.

literature

- Marjolein Degenaar: Molyneux's problem. Three Centuries of Discussion on the Perception of Forms. Archives internationales d'histoire des idées, vol. 147. Kluwer, Dordrecht 1996.

- Marjolein Degenaar, GJC Lokhorst: The Molyneux Problem . In: Sami Juhani Savonius-Wroth, P. Schuurman, J. Walmsley (Eds.): The Continuum Companion to Locke. Continuum, London / New York 2010, pp. 179–183.

- Gareth Evans : Molyneux's Question . In: Gareth Evans: Collected Papers. Edited by A. Phillips. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1985.

- Marius von Senden: The concept of space in the blind-born before and after the operation. Dissertation University of Kiel 1932.

- Zemplen, Gabor: Long-discussed problems of perception: The moon illusion and the Molyneux problem . In: imagination. Perception in art. Graz 2003, ISBN 3-88375-758-6 , pp. 198–228.

Web links

- Marjolein Degenaar and Gert-Jan Lokhorst: Molyneux's problem. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Locke, John: An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding. ( Memento of March 9, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (original text in English)

- Locke, John: An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding. (German translation from 1872)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c John Locke : An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding ., London: Printed for Tho. Basset hound Sold by Edw. Mory, 1690 , book 2, chapter 9

- ↑ George Berkeley: The Theory of Vision, or Visual Language shewing the immediate Presence and Providence of A Deity, Vindicated and Explained , 1733

- ↑ Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz: New Essays on Human Understanding translated and edited by Peter Remnant and Jonathan Bennett, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1981, pp. 136f.

- ^ Voltaire: Elements de philosophie de Newton in: Voltaire, Oeuvres complètes, vol. 15, pp. 183-652. Oxford: Alden Press, (1740) 1992.

- ↑ Denis Diderot: Letter on the Blind (1749): in Michael J. Morgan: Molyneux's Question: Vision, Touch, and the Philosophy of Perception , Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1977

- ^ Denis Diderot: Philosophische Schriften , first volume, Berlin 1961, pp. 60f.

- ^ Julien Offray de La Mettrie: L'histoire naturelle de l'âme. In: Oeuvres philosophiques. Hildesheim, New York 1970.

- ^ Hermann von Helmholtz: Manual of physiological optics , Leopold Voss, Hamburg and Leipzig 1856

- ^ William James: The Principles of Psychology , New York: Dover, (1890) 1950.

- ↑ Martin Giese: Sport and movement instruction with the blind and visually impaired - Theoretical basics - specific and adapted sports: Volume 1: Theoretical basics - specific and adapted sports , Meyer & Meyer Sport; Edition: 1st edition (October 29, 2009), pp. 14ff, ISBN 3-89899-425-2

-

↑ William Molyneux: Letter to John Locke , 7 July 1688, in: The Correspondence of John Locke (9 vols.), ES de Beer (ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978, vol. 3, no.1064.

- Dublin July. 7. 88

- A Problem Proposed to the Author of the Essai Philosophique concernant L'Entendement

- A Man, being born blind, and having a Globe and a Cube, nigh of the same bignes, Committed into his Hands, and being taught or Told, which is Called the Globe, and which the Cube, so as easily to distinguish them by his touch or feeling; Then both being taken from Him, and Laid on a Table, Let us Suppose his Sight Restored to Him; Whether he Could, by his sight, and before he touch them, know which is the Globe and which the Cube? Or Whether he Could know by his Sight, before he stretch'd out his Hand, whether he Could not Reach them, tho they were Removed 20 or 1000 feet from Him?

- If the Learned and Ingenious Author of the Forementiond Treatise think this Problem Worth his Consideration and Answer, He may at any time Direct it to One that Much Esteems him, and is,

- His Humble Servant

- William Molyneux

- High Ormonds Gate in Dublin. Ireland

- ↑ Michael Bruno, Eric Mandelbaum: Locke's answer to Molyneux's thought experiment , History of Philosophy Quarterly, Volume 27, Number 2, April 2010, pp. 165f.

- ↑ In the original: “'Suppose a man born blind, and now adult, and taught by his touch to distinguish between a cube and a sphere of the same metal, and nighly of the same bigness, so as to tell, when he felt one and the other, which is the cube, which is the sphere. Suppose then the cube and sphere placed on a table, and the blind man be made to see: quaere, whether by his sight, before he touched them, he could now distinguish and tell which is the globe, which the cube? ' To which the acute and judicious proposer answers, 'Not. For, though he has obtained the experience of how a globe, how a cube affects his touch, yet he has not yet obtained the experience, that what affects his touch so or so, must affect his sight so or so; or that a protuberant angle in the cube, that pressed his hand unequally, shall appear to his eye as it does in the cube. ' - I agree with this thinking gentleman, whom I am proud to call my friend, in his answer to this problem; and am of opinion that the blind man, at first sight, would not be able with certainty to say which was the globe, which the cube, whilst he only saw them; though he could unerringly name them by his touch, and certainly distinguish them by the difference of their figures felt. "

- ↑ In the original: “For though he has obtain'd the experience of, how a Globe, how a Cube affects his touch; yet he has not yet attained the Experience, that what affects his touch so or so, must affect his sight so or so; or that a protuberant angle in the Cube, that pressed his hand unequally, shall appear to his eye, as it does in the Cube. "

- ↑ Silke Pasewalk: "The five-fingered hand": The importance of sensory perception in the late Rilke , De Gruyter; Edition: 1st, 2002, ISBN 3-11-017265-8 , pp. 106ff.

- ↑ a b c d e Patricia Tegtmeier: Multimodal integration of incongruent object information in visual and haptic sensory modality , dissertation, Hamburg 2003

- ^ A b c Michael J. Morgan: Molyneux's Question: Vision, Touch, and the Philosophy of Perception , Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1977, pp. 19ff

- ↑ a b Marjolein Degenaar: Molyneux's problem: Three Centuries of Discussion on the Perception of Forms , London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 1996

- ↑ Erika Sophie Hopmann: The organization of the senses: Perception theory and aesthetics in Laurence Sternes Tristram Shandy , Königshausen & Neumann, 2008, p. 43f. ISBN 3-8260-3675-1

- ^ A b Gareth Evans: Molyneux's Question , in: Collected Papers , Oxford, Clarendon, 1985, pp. 364-99.

- ↑ James van Cleve: Reid's answer to Molyneux's question , The Monist , April 01, 2007

- ↑ Caroline Welsh, Christina Dongowski, Susanna Lulé (eds.): Senses and understanding. Aesthetic modeling of perception around 1800 . Würzburg 2002. pp. 44f.

- ↑ Shaun Gallagher: How the Body Shapes the Mind , Oxford Univ. Press, 2005, ISBN 0-19-927194-1

- ↑ Richard Held, Yuri Ostrovsky u. a .: The newly sighted fail to match seen with felt. In: Nature Neuroscience. 14, 2011, pp. 551-553, doi: 10.1038 / nn.2795 .