Letter on the blind for use by the sighted

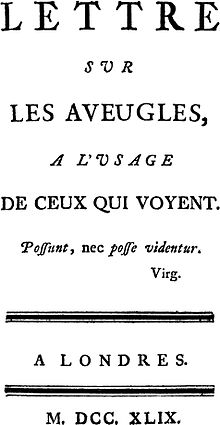

Letter about the blind for use by the sighted (the original title in French was Lettre sur les aveugles à l'usage de ceux qui voient ) is an essay by the French author Denis Diderot , printed in London in 1749.

In his philosophical investigation, which was written in the form of a letter, Diderot put forward the thesis “that the state of our organs and our senses has a great influence on our metaphysics and our morals”. In this letter, for the first time, he clearly and unequivocally represented a materialist - atheist position.

Historical background

The addressee of the letter is the writer M me de Puisieux , with whom Diderot had a temporary relationship and whom he supported financially for a long time. Since the early 18th century, star operations were carried out in Paris - with the active participation of spectators. a. by the ophthalmologist Michel Brisseau (1676-1743). After successful eye operations, which also enabled people born blind to see , a debate arose in philosophical and literary circles about the fundamentals of perception. M me de Pusieux intended to observe such an operation.

Because of this writing Diderot was imprisoned by a lettre de cachet from July 24, 1749 to November 3, 1749 in the state prison of Vincennes . The arrest came at a time when preparations for the printing of the first volume of the Encyclopédie were in full swing, and publication was jeopardized by the arrest of Diderot. Diderot's publisher and financier Le Breton , Michel-Antoine David , Laurent Durand and Claude Briasson sent petitions to the Count d'Argenson , Secretary of State for Louis XV. and the custodian of the National Library , who was still friends with M me de Pompadour at the time, to the universally hated Police Minister Nicolas René Berryer, who was responsible for censorship, and to the King's Chancellor, Henri François d'Aguesseau . The conditions of detention in Vincennes were comparatively mild, Diderot was able to move freely within the donjon , receive visits, e.g. B. by Jean Jacques Rousseau , contact employees and give them work instructions.

He was released after a good three months and was able to continue working.

The imprisonment led Diderot to be more careful and careful when formulating and publishing texts, with the aim of outsmarting the censors. Texts deemed too risky stayed in the drawer. However, from this point on he no longer published his writings anonymously.

A later addition by Diderot to his investigation ( Addition à la lettre sur les aveugles à l'usage ce ceux qui voient ) appeared in 1782 in Grimm's and Jacques-Henri Meister's exclusive, handwritten Correspondance littéraire , which was only distributed to subscribers. They were only published in a work edition in the 20th century.

The motto

Diderot prefaces his letter with a quote from Virgil's Aeneid , albeit in a modified form. From possunt quia posse videntur (translated from the Latin, they can because they think they can do it ') is possunt nec posse videntur (≈, they can, although it seems they can not do it'). The sense of the Virgil quote is practically reversed in Diderot's formulation.

content

Diderot begins his deliberations with a visit to the blind man von Puisaux, then goes into detail about the mathematician and professor at Oxford Nicholas Saunderson , and ends his letter with a discussion of the Molyneux problem .

The blind man from Puisaux

The blind man from Puisaux was distinguished by a particular refinement of the sense of touch and hearing. He had knowledge of the objects through the sensation that was finely developed in his fingertips. He had a precise sense of time, recognized symmetry , the external shape of forms, the localization and distance of things in space, which he could assess more precisely than a sighted person. His concept of beauty deviated from the understanding of a sighted person: "For the blind, beauty is only a word when it is separated from usefulness". (P. 52) Diderot's opinion that “the state of our organs and our senses have a great influence on our metaphysics and our morals” (p. 58) is confirmed by the blind man. Theft is a serious crime for him, since he is at a disadvantage as a perpetrator and as a victim in relation to the sighted. He has no understanding of the moral code of clothing, because without a sense of sight he also loses a sense of shame, just as the feeling of wrongdoing in a person equipped with all the senses decreases with increasing spatial distance. "The direct connection of moral norms with sensual perception leads to a relativization of moral concepts".

Saunderson

In his letter, Diderot continues with reflections on how the “idea of figures” is formed in a man born blind (p. 60). The blind man's excellent memory, his ability to perceive things in a more abstract way, predestine him to “separate the perceptible properties of a body through thinking”. Diderot concludes that "the sensations he has gained through the sense of feeling [...] form the basic forms of his ideas". Blind people are not distracted by visual impressions and are therefore better able to perceive things in a more abstract way and are less subject to deception in questions of “ speculation ”. This applies to both physics and metaphysics (p. 63). He is exemplified by the blind Nicholas Saunderson , author of a textbook for algebra, inventor of a calculating machine for the blind and professor at Cambridge, where he a. a. Taught math, astronomy and optics.

The centerpiece of the report is a fictional conversation between Saunderson on his deathbed and the clergyman Gervasius Holms about the existence of God. In his text, Diderot refers to a conversation between Saunderson and the clergyman, which is just as fictional as the biography of Saunderson, written by William Inchlif, to which Diderot refers.

The Molyneux problem

In the last part of his essay, Diderot deals with the Molyneux problem .

- Can a blind person who has been enabled to see with the help of an operation, simply by looking at them - without touching them - distinguish a ball from a cube?

The question was first asked by William Molyneux in a letter to John Locke . A publication by the English anatomist and surgeon William Cheselden , who had successfully performed eye surgery on a 13-year-old boy, subsequently led to a debate about the foundations of perception, which the philosophical luminaries of the time, such as George Berkeley , Étienne Bonnot de Condillac , to which Diderot goes into detail, Leibniz, Locke or Voltaire involved and which are the contents of the last part of his letter.

Diderot questions both the reliability of the experiment and the interpretation of the result. In his methodological criticism, he goes into the arrangement and implementation of the experiment. The patient was immediately questioned in bright light, which could also hinder a healthy person from seeing, instead of initially leaving him in the usual darkness, giving the eye the opportunity to exercise, waiting for complete healing and gradually getting used to the light ( P. 92). The subsequent survey was conducted in front of a curious audience instead of a panel of experts - scientists, doctors, philosophers - who should also be careful and careful with each question.

Following on from his methodological criticism, as in the passage on Saunderson, he touches upon questions of the philosophy of language : Provided that the blind person can see clearly enough after a successful operation to distinguish the individual things from one another, he would then be immediately able to understand the things whom he felt to give the same name as those he now saw? (P. 82) What could someone say who is not used to “reflecting and reflecting on himself”? (P. 94) Diderot assumes that there are people who are involved in philosophy, physics and in the case of the geometric bodies of the experimental system are trained in mathematics, it would be easier to bring felt and perceived things into agreement with "the ideas that he gained through the sense of feeling", and to convince oneself of the "truth of their judgment" (p. 95) . He assumes that this process is much faster in people who are trained in abstract thinking than in people who are poorly educated and have no practice in reflection .

Addendum

A good thirty years later, Diderot wrote an addition à la lettre sur les aveugles , in which he mainly refers to Mélanie de Salignac , a niece of Sophie Volland , who had been blind since she was two. After listing a series of observations he has made in the meantime with various blind people, he mainly corrects his earlier assumptions that “the blind are generally inhumane” (p. 59), which Melanie “could never forgive” ( P. 103). Her kindness and empathy made her the darling of the family. Because of the upbringing by her mother, she had the "very finest sense of shame", which Diderot had denied to the blind in his letter and hereby corrected.

Reception in Germany

While Diderot's early writings - including the letter on the blind - were hardly noticed in France because of the efficiency of state censorship, they were discussed in detail in Germany shortly after their publication in learned papers, between 1746 and 1756 alone seventy times. Herder leads his signature Plastic (1778), in which he called a "rehabilitation of touch as an aesthetic sense" postulated - in the opposite position to the established art theory that the sense of sight gave priority - with a summary of one of the fundamental tenets of Diderot's Essay one. The fundamental importance of the sense of touch for the exploration of the world and world experience with Diderot serves as a reference.

In 1808 Johann August Zeune , the founder of the Berlin Institute for the Blind and founder of education for the blind in Germany, published and commented on the Diderot text in his book Belisarius . Zeune's pedagogical manual for the education of the blind was discussed in detail shortly after it appeared in the Jenaische Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung in October 1808 and sparked a public debate about the possibility of educating the blind.

expenditure

- French

- Lettre sur les aveugles à l'usagede ceux qui voient In: Diderot: Œuvres complètes. Ed. critique et annotée Herbert Dieckmann , J. Vallot. Vol. 4. Paris 1978.

- Addition à la lettre sur les aveugles à l'usage ce ceux qui voient . Paris 1972. [1]

- German

- Letter about the blind. For the use of the sighted. With an addendum (1749). In: Diderot: Philosophical writings. Edited and translated from French by Theodor Lücke. Vol. 1. Berlin, Aufbau-Verlag 1961.

- Letter about the blind, for use by the sighted from 1749. In: Diderot: Philosophische Schriften. Edited by Alexander Becker. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a. M. 2013. (Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Wissenschaft.) ISBN 3-518-29684-1

literature

- Andrew Benjamin: Endless touching: Herder and sculpture . In: Aisthesis. Vol. 4. No. 2011. Full text

- Natalie Binczek : Contact: The sense of touch in Enlightenment texts . Tübingen 2007. (Studies on German Literature). ISBN 978-3-484-18182-3 Chapter 3: A media theory of the sense of touch: Diderot. Pp. 134-171.

- Marjorie Degenaar: Three Centuries of Perception of Forms. Dordrecht 1996. (Archives internationaux d'historie des idées. 147.) ISBN 0-7923-3934-7

- Jean Firges : "Lettre sur les aveugles", in dsb .: Denis Diderot: The philosophical and literary genius of the French Enlightenment. Biography and work interpretations. Sonnenberg, Annweiler 2013, ISBN 978-3-933264-75-6 , pp. 17-22 (in German)

- Katia Genel: La Lettre sur les aveugles de Diderot: l'expérience esthétique comme expérience critique In: Le philosophoire. No. 21/3. 2003. pp. 897-112. [2]

- Kai Nonnenmacher: The black light of modernity. On the aesthetic history of blindness. Berlin 2006. ISBN 3-484-63034-5 In it: Diderot and the modernity of blindness . Pp. 47-92.

- Hans P. Spittler-Massolle: Blindness and the pedagogical view of the blind. The "Letter on the Blind for Use by the Sighted" by Denis Diderot and its meaning for the concept of blindness. Frankfurt 2001. ISBN 978-3-631-37595-2

- Brundhild Weihinger: Lettre sur les aveugles à l'usage de ceux qui voient. In Kindler's New Literature Lexicon, KLL. Edited by Walter Jens. Vol. 4. Munich 1998. pp. 672-673; 674.

Web links

- Diderot's Internment at Vincennes, letters and documents

- Stéphane Lojkine: Beauté aveugle et monstrusité sensible: détournement de la question esthétique chez Diderot

- Margaret Jourdain (Ed.): The Letter Of The Blind. In: Diderot Early Philosophical Works. The Open Court Publishing Company 1916, pp. 68–141, English edition, online (PDF; 2.7 MB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Michel Brisseau: Traité de la cataracte et du glaucoma. Paris, L. D'Houry, 1709.

- ^ Chronology: Henri François D'Aguesseau, overview in French, online

- ↑ Virgil Änäis. Book 5, line 231

- ↑ Kai Nonnenmacher: The black light of modernity: On the aesthetic history of blindness . Walter de Gruyter, 2006, ISBN 3-11-092110-3 , p. 84 (388 p., Limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Mark Paterson: The Senses of Touch: Haptics, Affects and Technologies. Berg, New York 2007, p. 34.

- ↑ All literal Diderot quotations from Diderot: Philosophical writings. Vol. 1. Berlin 1961.

- ↑ Brunhilde Weihinger. KLL. P. 672.

- ↑ William Inchlif: The life and character of Dr. Nicholas Saunderson, late Lucasian Professor of the mathematics in the university of Cambridge; by his disciple and friend William Inchlif. Dublin 1747.

- ^ Robert Edward Norton: Herder's Aesthetics and the European Enlightment. New York 1992, p. 205, annot. 8th; Marie-Hélène Chabut: Denis Diderot: extravagence et génialité. Amsterdam 1998, p. 70.

- ↑ “ A Man, being born blind, and having a Globe and a Cube, nigh of the same bignes, Committed into his Hands, and being taught or Told, which is Called the Globe, and which the Cube, so as easily to distinguish them by his touch or feeling; Then both being taken from Him, and Laid on a Table, Let us Suppose his Sight Restored to Him; Whether he Could, by his sight, and before he touch them, know which is the Globe and which the Cube? Or Whether he Could know by his Sight, before he stretch'd out his Hand, whether he Could not Reach them, tho they were Removed 20 or 1000 feet from Him? ”(William Molyneux: A Problem Proposed to the Author of the Essai Philosophique concernant L'Entendement. July 7, 1688.)

- ↑ Cf. Anne Saada: Diderot in Germany in the 18th Century - Spaces or Fields? Translated from the French by Claudia Albert. In: Markus Joch; Norbert Christian Wolf (ed.): Text and field. Bourdieu in literary practice. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer, 2005. (Studies and texts on the social history of literature.), Pp. 73–87.

- ↑ Johann Gottfried Herder: Plastic. Some perceptions about form and shape from Pygmalion's dream. Riga: Johann Friedrich Hartknoch, 1778.

- ↑ See review on August Zeune: Belisar. About teaching the blind. Berlin: Weiß, 1808. In: Jenaische Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (October 21, 1808), No. 247, Sp. 137–142.