Monopoly competition

The monopoly competition or the monopoly competition (also heterogeneous polypol ) is a term developed by Edward Hastings Chamberlin , which characterizes a market form between the monopoly and the complete competition. This is a polypole in an imperfect market .

There are many small providers on this market who are able to vary the price. The imperfection is caused by the fact that, on the one hand, the consumers have spatial, temporal or material preferences and that the traded goods are comparable but differ in certain characteristics ( product differentiation ). This allows the consumer a wide choice between substitutable products that are manufactured and offered by specialized companies . Due to the product differentiation, each supplier has a certain monopoly leeway within which it is possible for him to determine price or quantity , similar to a monopoly . In this monopolistic area the rule of profit maximization applies: marginal revenue equals marginal costs . If the supplier leaves this area, the price is set by the market, as is the case with the Polypol, and if the prices are higher, the demand is lost to the competition.

In reality, this type of market is quite common. Examples of such markets are markets for numerous goods and services for daily needs (e.g. bread, books, fruit, hairdressers, dry cleaners).

The case of monopolistic competition is formally represented with the help of a price-sales function that is bent twice .

Alternative definitions and demarcation

Further definitions are:

- "A market in which companies can freely enter and each produce their own brand or version of a differentiated product."

- “The market model of monopolistic competition can often be found in reality. It represents the polypol on the imperfect market (polypolistic competition), on which many suppliers and many buyers act independently of each other ... "

You can divide markets according to various criteria. Depending on the perspective, markets are to be differentiated according to market participants ( monopoly , oligopoly , polypol ), demand intensity ( mass market , shrinking market ) or also according to the goods traded ( goods or product market , factor market ). The model of monopoly competition combines different market forms and models, including monopoly and oligopoly, with the characteristics of competition .

Model description

With a sufficiently strong product differentiation , it is possible for the individual supplier to assume a monopoly position, albeit a weak one. Product differentiation means that the products are similar but still have noticeable differences. The goods can be represented as imperfect substitutes. Within certain limits, the provider can change its price like a monopoly. In a market with, albeit a few, other providers, every strategic market measure always leads to a reaction from competitors.

Edward Hastings Chamberlin developed a theory which takes monopoly elements into account in the market form of the heterogeneous polypole . In the heterogeneous Polypol, the providers are able to vary the price . Chamberlin assumes that the individual provider tries to achieve the maximum profitable price, i.e. acts like a monopoly . The profit-maximum price-quantity combination is therefore for each provider in his Cournot point . Since market entry is free and profits are made, new providers enter the market with comparable products and the price-sales function of previous providers shifts towards the origin. If profit is ultimately no longer possible, the average cost curve affects the price-sales function (Chamberlin's tangent solution).

In contrast to Chamberlin's tangent solution, Erich Gutenberg assumes that the individual price-sales functions are kinked twice due to preferences and lack of transparency, i.e. that a monopoly area is in the polypolistic price-sales function. Within this area, the company can define its action parameters without fear of a reaction from the competition. ( Gutenberg function ).

The model

Characteristics

- As part of product differentiation , goods are brought onto the market that represent imperfect substitutes . In some cases, the difference is only recognizable to the customer, who consumes through differences in quality and price as well as brand loyalty.

- Example: Kellogg 's cornflakes and a no-name product have the same purpose, but must be distinguished by the above-mentioned characteristics.

- The pricing policy assumes that companies behave like monopolists. The greater the degree of product differentiation, the more independent the price can be. Furthermore, the pricing policy is differentiated through special customer programs, such as student or senior rates , discount campaigns and also through a general price classification.

- The companies are seen as symmetrical; that is, they have identical demand and cost functions.

- There are no barriers to market entry in this model ; on the contrary, the absence of these ensures that a price levels off equal to the average cost. If the price is above the average cost, new players enter the market; if it falls below this for a market participant, those affected leave the market. In the Krugman model, the profits that arise anyway (price above marginal costs) result from the fact that the elasticity of demand here allows a range on the price-sales function in which customers change providers less quickly than the respective company increases the price. In this area, the price elasticity of demand ( ) is not less than ; whereby a price increase leads to a decrease in demand .

- It is characteristic of this type of competition that the effects of a price increase of one's own products on the prices of competitors are masked out; every company takes the prices of its competitors for granted. This is an essential difference to the oligopoly .

Basic assumptions

The higher the demand for a product and the higher the price of the competitors, the greater the sales. As a result, one can assume that sales will decrease as the number of competitors increases. Assuming that all companies in the industry are symmetrical, the result is an identical demand and cost function for all companies.

Market equilibrium

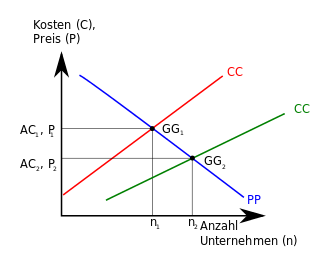

The market equilibrium in monopolistic competition assumes that the offer price (P) and the average costs (AC) are related to the number of providers in the respective market segment. It is also assumed that the demand and cost functions are the same for all companies.

- Number of companies and average costs :

The cost function states that, under otherwise constant conditions, the average costs (AC) increase with the number of competitors, since the individual company produces and sells less. The relationship between the number of companies and the average costs is represented by the rising CC curve with the equation .- With:

- : the fixed costs

- : the total market demand

- : the marginal costs (with linear cost function: variable unit costs )

- : the number of providers in this market segment

- : Quantity requested from a provider

- With:

- Number of activities and the price:

As the number of companies increases, so does the price that each individual provider can charge. This results in a falling PP curve with the equation

- With:

- with : the industry-specific sales change after price changes

- With:

- Ratio of PP and CC :

To the left of the equilibrium point (GG), the industry is making profits , which attracts new providers. As the number of competitors increases, the offer price falls and the average costs rise. The market situation is approaching equilibrium. If the market is to the right of point GG, losses are recorded and the branch is emigrated. The average costs exceed the price function. As a result, the remaining suppliers will reduce their supply, so that there is a tendency towards equilibrium. - Number of companies in equilibrium:

The point GG represents the long-term equilibrium. This is where the PP curve and the CC curve intersect. In the above figure this is in n and AC, P. At this point, the industry does not make any profits, but neither does it make any losses since the average cost is equal to the price. Algebraically, the equilibrium point can be derived by equating the price and average cost functions as follows:

Restrictions

The model of monopolistic competition only applies to a few industries. The assumption that every company behaves as a “real” monopoly is unsustainable in reality. Rather, the individual providers are aware of their influence on the behavior of their competitors. In the model of monopolistic competition, two typical behavioral patterns of the oligopoly are excluded. On the one hand, there is the coordinated behavior ( collusion ), which is unfavorable for consumers, since the price is kept above the calculated profit level. The coordination can take place through explicit contracts or tacit coordination strategies. The second possibility is strategic behavior, which creates market barriers by adding additional capacity . These targeted decisions reduce profits, but they influence the behavior of the competition and prevent potential rivals from entering the market. A model is always limited to the essential factors in order to represent reality in a simplified manner. Here, too, simplification is of great importance for understanding, especially in relation to foreign trade and in the context of the globalization of markets.

Model extension: foreign trade

Foreign trade in monopoly competition is intended to expand the national market into the world market . The “new” market size eases the restrictions on the possible production volume . Since the nations can cooperate with one another in the enlarged market and there is also more space for a larger number of companies, it is possible for them to produce a greater variety of goods and to vary the price. Consumers are offered lower prices as well as a large number of product variants. In a larger market there is more space for a higher number of companies and the scope for price increases. Even if there are no significant differences in resources or technology between companies , there are mutual benefits. These can arise within the scope of the opportunity costs, since one country, for example, has lower production costs for a product than another. In addition, the average cost is reduced by the larger and more diverse production volume. Further advantages of large markets are a larger number of companies on the supply side, which can also achieve higher sales. On the consumer side, lower prices and a greater variety of products are significant.

Effects of Market Expansion

A comparison of two markets with different total sales shows that the CC curve of the larger market is below that of the smaller market. This means that the enlarged market allows more suppliers to operate in the market, which increases the variety of products and at the same time decreases the price. With the price and the possibility of producing more products, the average costs (AC) of the providers also decrease.

Since the formula for the price does not take into account total sales, the PP curve does not shift due to a market expansion.

- .

conclusion

By expanding the market , companies have the opportunity to increase production while lowering average costs. This becomes clear through the downward shift of the CC curve, from point GG 1 to GG 2 . This is a consequence of the increasing number of companies and, at the same time, falling prices. The situation in point GG 1 , with little product selection and relatively high prices, is worse for consumers than the situation in point GG 2 , with lower prices and more choice.

Examples

- A baker is in competition with a large number of competitors who considerably restrict his scope for setting prices. However, the only baker in a part of the city can charge a slightly higher price than its competitors in the surrounding area, since its customers have a spatial preference, as they shy away from long journeys when buying an everyday item. Only when the local bakery is significantly more expensive than its competitors does the further journey pay off for the customer.

- The automotive industry in Europe corresponds to the market model of monopoly competition, as there are many manufacturers such as Ford, General Motors, Volkswagen, Renault, Peugeot, Fiat and others. a., there are also a large number of vehicle models and classes.

- Further examples that can be assigned to monopoly competition due to product differentiation are: market for toothpaste, detergent market, coffee market, retail trade.

Compared to full competition

| complete competition | monopoly competition | |

|---|---|---|

| Market form | Polypol on a perfect market |

Polypol in an imperfect market

|

| Products | homogeneous goods | homogeneous goods heterogeneous goods "imperfect substitutes" |

| price | cannot be influenced " market price " |

can be influenced within the monopolistic scope

|

| Market entry / exit | free | free |

Profit

|

yes no |

yes no |

literature

- Stoetzer: Economics and Microeconomics. 1st edition, Fachbibliothek Verlag, Büren 2014, ISBN 978-3-932647-58-1

- Seidel, Temmen: Fundamentals of Economics. 18th edition. Gehlen, Bad Homburg vor der Höhe 2000, ISBN 3-441-00194-X , pp. 123–127.

- Krugman, Obstfeld: International Economy. 7th edition. Pearson, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8273-7081-7 , pp. 167-174.

- Joseph E. Stiglitz: Economics. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-23379-3 .

- Robert S. Pindyck, Daniel L. Rubinfeld: Microeconomics. 7th edition, Pearson, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-8273-7282-6 , Chapter 12.1: Monopolistic competition. Pp. 575-580.

- Monopoly competition. In: Duden Economy from A to Z: Basic knowledge for school and study, work and everyday life. 5th edition, Bibliographisches Institut, Mannheim 2013, here online edition of the Federal Agency for Civic Education , 2013.

Web links

- Monopoly competition - definition in the Gabler Wirtschaftslexikon

Individual evidence

- ↑ Heinz-Dieter Hardes, Alexandra Uhly: Grundzüge der Volkswirtschaftslehre, Munich 2007, p. 246.

- ↑ Pindyck / Rubinfeld (2005): Microeconomics. 6th edition. Munich: Pearson, p. 570.

- ↑ Seidel / Temmen (2000): Fundamentals of Economics. 18th edition. Bad Homburg vor der Höhe: Gehlen, p. 126.

- ↑ Gabler Wirtschafts-Lexikon.- Paperback cassette with 6 vol., 12th edition. Wiesbaden: Gabler, Volume 4, LP, pp. 471-472.

- ↑ Krugman; Obstfeld (2006): International Economics. Pearson Verlag, Munich: pp. 167-170.

- ↑ Krugman; Obstfeld (2006): International Economics. Pearson Verlag, Munich: pp. 167-170; Kempa, Bernd (2012): International Economics. Kohlhammer Verlag, Münster: pp. 117–122.

- ↑ Krugman; Obstfeld (2006): International Economics. Pearson Verlag, Munich: pp. 167-170.

- ↑ Krugman / Obstfeld, p. 170.

- ↑ Susanne Wied-Nebbeling: Market and Price Theory. Cologne 1997, p. 113.

- ↑ cf. Krugman / Obstfeld (2006): International Economy. 7th edition, Munich: Pearson, page 169.

- ↑ cf. Krugman / Obstfeld (2006): International Economy. 7th edition, Munich: Pearson, page 171.

- ^ Krugman / Obstfeld, p. 174.

- ^ Krugman / Obstfeld (2006): Internationale Wirtschaft. 7th edition. Munich: Pearson, p. 167 ff.