Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley (* around 1753 probably in the Senegambia region , West Africa, † December 5, 1784 in Boston ) was the first African-American poet whose works were published.

life and work

Believed to be born on the Gambia River , she was sold into slavery at the age of seven . It was bought in Boston by tailor John Wheatley as a gift for his wife Susanna in around 1761. She was baptized in the name of Phillis after the ship on which she was brought to America and raised as a Christian. The Wheatleys made sure the gifted girl received a good education, including classes in Latin , Greek, mythology, and history.

Her first poem ( On Mssrs. Hussey and Coffin ) she published in 1767 at the age of thirteen in the Rhode Island newspaper Newport Mercury. This first poem is already typical of her work, which was based on neoclassical poetry based on the model of Alexander Pope . Many of her poems have a Christian uplifting content, and many of them are dedicated to religious celebrities. She gained widespread fame in 1771 with an elegy on the late Methodist preacher George Whitefield ( On the Death of Reverend Whitefield ), whom she probably heard preached herself. The poem was printed not only in Boston but also in London, making her famous on both sides of the Atlantic - with interest focused at least as much on her skin color as on the literary quality of her poems. Voltaire , for example, in a letter to Baron Constant de Rebecq in 1774 cited Wheatley as counter-evidence for his racist claim that there were no black poets.

In 1772 the Wheatleys tried in vain to find a publisher in Boston who would print Phillis' poems in book form. With many of the refusals alleging that she couldn't have written the poems herself, the Wheatleys arranged for a group of select Boston notables, including Thomas Hutchinson , the governor of Massachusetts , to be interviewed . Although it is not known how this tribunal actually presented itself - the girl was probably tested in her Bible stability and her knowledge of the classical languages - but after passing the examination they signed a certificate in which they assured that Phillis Wheatley was not the author There is doubt.

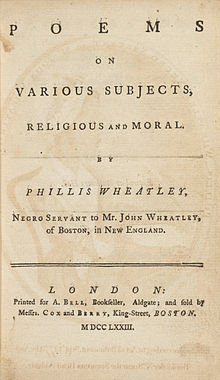

When, despite this confirmation, there was still no publisher, Susanna Wheatley threaded an implementation of the book project in England through English patrons such as Selina, Countess of Huntingdon . Phillis Wheatley traveled to London in the summer of 1773 to accompany the advertising campaign in England. During her two-month stay, she was passed as a curiosity through the salons of the literary aristocracy, where she met, among others, Benjamin Franklin , at the time deputy postmaster for the British colonies in North America, who had been back in London since 1765. Shortly after returning to Boston, her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral appeared in September of that year with publisher Archibald Bell. The aforementioned certificate of their education preceded the volume.

Shortly after Phillis returned to Boston, her owner Susanna Wheatley died, and Phillis was granted freedom by October of that year at the latest. If its previous owner, John Wheatley, was an avowed loyalist , Phillis Wheatley, as a free black, now stood up with her poems for the growing independence movement that culminated in the founding of the United States in 1776. One of her best known poems is an ode to the future President George Washington ( To His Excellency General Washington , 1775). Less enthusiastic about her poetry was Thomas Jefferson , who was one of her sharpest critics. The poet hardly deals with her own situation. One of the few works that refers to the slavery, On Being Brought From Africa to America ( from Africa to America ):

|

'TWAS mercy brought me from my Pagan land, |

Grace brought me out of heathen land, |

Around 1778 she married the free black grocer John Peters, with whom she had two children; both died in infancy. After her husband left her, she got by as a waitress and became increasingly impoverished. She died in childbed at the age of 31, her third child a few hours after her. A second volume of poetry she had worked on was never published. Of Wheatley's probably much more extensive work, only 56 poems and 22 letters have survived. Most recently, a previously unknown poem from her pen became known in 1998. The Ocean manuscript was put up for auction by a private seller at Christie's auction house for $ 68,500.

reception

Wheatley's poetry is generally not well respected in modern literary criticism and has often been interpreted as a mere imitation of neoclassical style models devoid of originality. Even critics with a post-colonial theoretical background or representatives of an essentialist “black aesthetic” influenced by the civil rights movement , who endeavor to create a counter- canon of American literature that also takes account of the literary products of women and / or blacks , have found it difficult, Wheatley for such a thing The project because her observance of contemporary conventions and ways of thinking seemed to them to be an ingratiation to the whites - her poems appear to them as the “product of a white spirit,” the poet has therefore sold her soul.

This assessment has only been challenged in recent years by well-meaning critics, who attested Wheatley's poems to be quite subversive, especially in their deliberate influence on the reader on the question of the legality of slavery and the dignity of black people. Its most prominent advocate is Henry Louis Gates, Jr. , who wrote in his introduction to a 1988 anxious reprint of Wheatley's works that she "single-handedly" established the tradition of African American literature by publishing the Poems on Various Subjects . Research now assumes that the first printed work by an African American was not by Wheatley, but by Jupiter Hammon , whose poem An Evening Thought was published as a leaflet in 1761.

literature

Factory editions

- John C. Shields (Ed.): The Collected Works of Phillis Wheatley. Oxford University Press, New York 1988. [The Schomburg Library of Nineteenth-Century Black Women Writers]

- Julian Mason (Ed.): The Poems of Phillis Wheatley: Revised and Enlarged Edition . University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1989.

- Phillis Wheatley: Complete Writings. Penguin, London 2001.

Secondary literature

- Mary McAleer Balkun: Phillis Wheatley's Construction of Otherness and the Rhetoric of Performed Ideology. In: African American Review 36: 1, 2002.

- Carmen Birkle: Border Crossing and Identity Creation in Phillis Wheatley's Poetry. In: Udo Hebel (Ed.): The Construction and Contestation of American Cultures and Identities in the Early National Period. Carl Winter University Press, Heidelberg 1999.

- Daniel J. Ennis: Poetry and American Revolutionary Identity: The Case of Phillis Wheatley and John Paul Jones. In: Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture 31, 2002.

- Astrid Franke: Phillis Wheatley, Melancholy Muse. In: New England Quarterly 77: 2 June 2004.

- Henry Louis Gates, Jr .: The Trials of Phillis Wheatley: America's First Black Poet and Her Encounters with the Founding Fathers. Basic Civitas, New York 2003.

- Henry Louis Gates, Jr .: Phillis Wheatley on Trial: In 1772, a Slave Girl Had to Prove She Was a Poet. She's Had to Do So Ever Since. In: New Yorker 78:43, January 20, 2003.

- Merle A. Richmond: Bid the Vassals Soar. Interpretive Essays on the Life and Poetry of Phillis Wheatley and George Moses Horton. Howard University Press, Washington DC 1974.

- William H. Robinson: Critical Essays on Phillis Wheatley. GK Hall, Boston 1982.

- William J. Scheick: Authority and Female Authorship in Colonial America. University Press of Kentucky, Lexington 1998.

- Kirstin Wilcox: The Body into Print: Marketing Phillis Wheatley. In: American Literature: A Journal of Literary History, Criticism, and Bibliography 71: 1, March 1999.

- Vincent Carretta: Phillis Wheatley: biography of a genius in bondage , Athens, Ga.: Univ. of Georgia Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0-8203-3338-0

Web links

- Phillis Wheatley. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Vincent Carretta: Introduction. In: Phillis Wheatley: Complete Works. Penguin, London 2001. p. Xiv.

- ^ Julian Mason: Ocean: A New Poem by Phillis Wheatley. In: Early American Literature 34: 1, 1999, pp. 78-83.

- ^ Summary of the critical assessments according to Scheick, p. 107 .; s. a Marsha Watson: A Classic Case: Phillis Wheatley and Her Poetry. In: Early American Literature 31: 2, 1996.

- ^ Benjamin G. Brawley: The Negro Genius. Biblo & Tannen, New York 1966, p. 16.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Wheatley, Phillis |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | African American poet |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1753 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Senegambia , West Africa |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 5, 1784 |

| Place of death | Boston |