New Zealand dwarf snail

| New Zealand dwarf snail | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

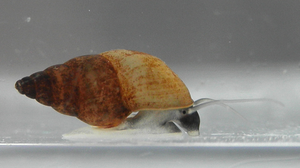

Right-hand picture of a New Zealand snail |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Potamopyrgus antipodarum | ||||||||||||

| ( JE Gray , 1843) |

The New Zealand pygmy snail ( Potamopyrgus antipodarum ) is a small species of shell snail that is common in freshwater and brackish water. Originally native to New Zealand, it has now been abducted almost all over the world as a neozoon and is also one of the most common aquatic snail species in Central Europe.

features

The housing of Potamopyrgus antipodarum is in Europe up to three, at most five millimeters long. Larger forms of up to twelve millimeters in length only exist in New Zealand itself. The elongated oval, conical housing consists of five to seven passages, which are separated from each other by a deep seam. The mouth is highly oval and reaches about 0.4 times the spindle length. The shell can be horn-colored or gray, sometimes almost white and is somewhat translucent, but often it is completely black due to organic and inorganic coatings. The living animal is predominantly white in color with a few dark spots or bands. As is typical for sea snails, the shell of the species is right-handed. Potamopyrgus can close the case mouth with a lid (operculum). The lid is horn-colored, not calcified and relatively thin, its surface shows a spiraling growth line, the center (nucleus) is slightly shifted from the center. In the active animal, the lid is on the back of the foot behind the center, with the longer side across the axis of the foot. The soft body has a radula with seven rows of teeth. A large gill (ctenidium) sits inside the mantle cavity. On the head there is a pair of relatively narrow tentacles, each with a black eye-spot near the base.

The shape of the shell of the New Zealand dwarf snail is morphologically highly variable. There are relatively slender, elongated populations, alongside others with a conical-oval, compact housing. In some individuals and populations, the normally smooth, somewhat glossy shell can have a keel on the outside of the passageways, which is also sometimes hairy or covered with scales.

Life cycle

The species is segregated. Outside of New Zealand, however, purely female populations predominate, and males are rarely found here. It reproduces here parthenogenetically . It is the only species within the sea snail in which parthenogenetic reproduction has been reliably proven. As a result of this mode of reproduction, the animals of a local population are usually genetically identical clones that differ very little from one another due to later mutations. During an investigation in England, very isolated individuals with a different genetic makeup were found. These are either descendants of rarer, less successful clones, or they can be traced back to extremely rare sexual reproduction. According to their mitochondrial DNA, all European animals belong to two haplotypes , which can be traced back to two (out of a total of seventeen) from New Zealand's North Island. Along a Habitatgradienten can already be in a confined space a genetic Kline with matched to the respective habitat conditions clones z. B. between deeper and near-shore water in the same lake.

Potamopyrgus females become sexually mature with a housing length of 2.75 to 3.5 millimeters. They do not lay eggs, but are viviparous ( ovoviviparous ). The eggs remain in a brood chamber, which is formed from an expansion of the oviduct in the mantle cavity, the snail later releases fully developed small juvenile snails. The young animals need about three months under favorable conditions until they reach sexual maturity themselves. A single brood can produce 20 to 120 young animals, around 230 per year. Depending on the climatic conditions, up to six generations per year are possible. The animals live to be around one year old. The breeding period is in the summer half-year.

ecology

New Zealand dwarf snails feed, as is generally the case with snail species, as grass by scraping off algae or organic coatings with their radula. You can also scrape off the surface of higher water plants (macrophytes) or dead substances such as wood or leaves (detritus). The species lives on substrate surfaces of all kinds, in addition to plants or stone surfaces, sand, clay or mud are colonized. It can reach extremely high population densities in its habitat. On the lake bed and in slowly flowing rivers, up to several hundred thousand individuals per square meter were found. With such mass occurrences, the entire substrate surface appears to consist of snails. Much lower population densities are reached in cold and nutrient-poor waters. The species can also successfully colonize springs and spring streams, but it clearly prefers organically polluted and disturbed waters. Its saprobic index of 2.3 indicates a preference for moderately to critically polluted waters in rivers ( water quality classes II to II-III). The preferred temperature is around 18 ° C, above around 24 ° C there is no longer any reproduction. The snails are not frost hardy and die almost completely at water temperatures of around 2 ° C. They are therefore absent in temporary bodies of water. It escapes unfavorable conditions by digging into the sediment. The species needs calcium levels in the water of at least 2 mg / l for its housing, more likely 4 mg / l for successful reproduction. It is absent in acidic waters and can only tolerate pH values below 6 for a very short time.

The species colonizes standing and flowing fresh water in New Zealand. But it is euryhaline and can live permanently in brackish water and reproduce there. That's how she lives B. widespread in river mouths (estuaries) and at the bottom of the entire Baltic Sea . It can survive for a long time in pure sea water at low temperatures, but cannot reproduce here. Freshwater and brackish water-dwelling animals represent different clones; animals from freshwater populations perish when they are transferred to salty water. Brackish water-adapted forms show good growth rates with a salt content of 5 per thousand, reproduction is possible up to around 15 per thousand.

distribution

The original home of the species is New Zealand (North and South Island), where other species of the genus live. From there, she was carried off to Great Britain in the 19th century, presumably with drinking or ballast water from ships. At first it only appeared in estuaries and port cities, but it spread rapidly and now inhabits waters of all types and locations. She was abducted to Australia just as early. The first German evidence, at the same time the first in continental Europe, took place in 1887 on the Baltic coast. The species gradually colonized almost all of continental Europe, but remained rather rare in the Mediterranean region and was only found late on the Balkan Peninsula (2004 in Bulgaria, 2007 in Greece).

The species continues to be distributed worldwide via the ballast water of ships. They were only introduced to Japan after 2000, and to Iraq in 2009. The first North American evidence was in 1987 in the Snake River , Idaho. Since then it has spread at breakneck speed. Today it populates a large area in the western United States. A second settlement center exists in the area of the Great Lakes . According to genetic analyzes, it can be traced back to an independent introduction. Since in North America, unlike in Europe, numerous endemic Hydrobid species occur in freshwater, the danger of these species becoming extinct through displacement is feared.

Taxonomy

Potamopyrgus antipodarum was first described by John Edward Gray after New Zealand animals as Amnicola antipodarum . Later it was placed in the new genus Potamopyrgus by William Stimpson (under the name Melania corolla Gould, 1847, a younger synonym ) . Unaware of this, Edgar Albert Smith described the species after animals he had found in the Thames estuary in England a second time as Hydrobia jenkinsi . The species was later described numerous times in different regions, e.g. B. in Australia as Paludina nigra . The identity of all of these forms with the New Zealand species was not proven until 1988 by WF Ponder. In older articles from Europe and Australia, the species is therefore mentioned under the synonymous names. The identity has been confirmed by molecular studies.

The genus Potamopyrgus , and thus also the species, were traditionally assigned to a broad family of water snails (Hydrobiidae), within the superfamily of the Rissooidea , according to morphological characteristics . The affiliation of the New Zealand lines to the family Hydrobiidae has been called into question by findings of molecular phylogeny. In 2013 Thomas Wilke and colleagues elevated the previous subfamily Tateinae of the Hydrobiidae to the new family Tateidae on the basis of genetic data, this view has prevailed.

During processing, it was also found that in New Zealand there are morphologically indistinguishable but genetically clearly separated forms ( cryptospecies ).

swell

- Thomas W. Therriault, Andréa M. Weise, Graham E. Gillespie, Todd J. Morris (2010): Risk assessment for New Zealand mudsnail (Potamopyrgus antipodarum) in Canada. Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Research Document 2010/108.

Individual evidence

- ↑ D. Weetman, L. Hauser, GR Carvalho (2002): Reconstruction of microsatellite mutation history reveals a strong and consistent deletion bias in invasive clonal snails, Potamopyrgus antipodarum. Genetics 162 (2): 813-822.

- ↑ T. Städtler, M. Frye, M. Neiman, CM Lively (2005): Mitochondrial haplotypes and the New Zealand origin of clonal European Potamopyrgus, an invasive aquatic snail. Molecular Ecology 14: 2465-2473. Doi : 10.1111 / j.1365-294X.2005.02603.x

- ↑ Sonja Negovetic & Jukka Jokela (2001): Life-history variation, phenotypic plasticity, and subpopulation structure in a freshwater snail. Ecology, 82 (10): 2805-2815. Doi : 10.1890 / 0012-9658 (2001) 082 [2805: LHVPPA] 2.0.CO; 2

- ↑ DEV (German Institute for Standardization eV) (2003): Biological-ecological water quality investigation: Determination of the saprobic index (revised version). German standard procedures for water, waste water and sludge analysis. Biological-ecological investigation of water bodies (group M). Berlin.

- ↑ a b Kathe R. Jensen (2010): NOBANIS - Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet - Potamopyrgus antipodarum - From: Identification key to marine invasive species in Nordic waters - NOBANIS www.nobanis.org, accessed on December 27, 2012

- ^ HG Spencer, RC Willan, B. Marshall, TJ Murray (2011): Checklist of the Recent Mollusca recorded from the New Zealand Exclusive Economic Zone. on-line

- ↑ Atanas A. Irikov, Dilian G. Georgiev (2008): The New Zealand Mud Snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gastropoda: Prosobranchia) - a New Invader Species in the Bulgarian Fauna. Acta zoologica bulgarica 60 (2): 205-207.

- ↑ Canella Radea, Ioanna Louvrou, Athena Economou-Amilli (2008): First record of the New Zealand mud snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum JE Gray, 1843 (Mollusca: Hydrobiidae) in Greece - Notes on its population structure and associated microalgae. Aquatic Invasions Volume 3, Issue 3: 341 - 344. doi : 10.3391 / ai.2008.3.3.10

- ↑ M. Urabe (2007): The present distribution and issues regarding the control of the exotic snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum in Japan. Japanese Journal of Limnology 68 (3): 491-496.

- ^ Murtada D. Naser & Mikhail O. Son (2009): First record of the New Zealand mud snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray 1843) from Iraq: the start of expansion to Western Asia? Aquatic Invasions Volume 4, Issue 2: 369 - 372. doi : 10.3391 / ai.2009.4.2.11

- ^ PA Bowler (1991): The rapid spread of the freshwater hydrobiid snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum in the middle Snake River, southern Idaho. Proceedings of the Desert Fishes Council 21: 173-182.

- ^ WF Ponder (1988): Potamopyrgus antipodarum - a molluscan colloniser of Europe and Australia. Journal of Molluscan Studies Volume 54 Issue 3: 271 - 285. doi : 10.1093 / mollus / 54.3.271

- ↑ T. Städler, M. Frye, M. Neiman, CM Lively (2005): Mitochondrial haplotypes and the New Zealand origin of clonal European Potamopyrgus, an invasive aquatic snail. Molecular Ecology 14: 2465-2473.

- ↑ Thomas Wilke, Martin Haase, Robert Hershler, Hsiuing Liu, Bernhard Misof, Winston Ponder (2013): Pushing short DNA fragments to the limit: Phylogenetic relationships of 'hydrobioid' gastropods (Caenogastropoda: Rissooidea). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 66 (3): 715-736. doi: 10.1016 / j.ympev.2012.10.025

- ↑ Martin Haase (2008): The radiation of hydrobiid gastropods in New Zealand: a revision including the description of new species based on morphology and mtDNA sequence information. Systematics and Biodiversity Volume 6, Issue 1: 99 - 159. doi : 10.1017 / S1477200007002630

Web links

- Potamopyrgus antipodarum inthe IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013.2. Posted by: Van Damme, D., 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2014.