Roman villa in Bignor

The Bignor Roman Villa is a former Roman villa near the modern village Bignor in the district of Chichester in the county of West Sussex in England . The villa is best known for its numerous mosaic floors . The remains can be viewed today. It is also one of the largest Roman villas from the time of the province of Britannia ( Britain ).

location

In ancient times, the villa was located on the so-called " Stane Street ", a Roman-era street that connected Londinium ( London ) with Noviomagus Regnorum ( Chichester ). The city was about half a day's walk from the villa.

Research history

The remains of the villa were discovered by chance around 1811 while plowing. They found themselves on the property of John Hawkings, who then summoned Samuel Lysons to lead the excavations. Immediately after the excavations, the mosaics were covered in order to preserve them for viewing. In 1815 a guide to the ruins appeared, probably the first of its kind in England. Samuel Lysons had drawings made of the mosaics, which at first apparently were sold individually and were only later published in the volume Reliquuiae Britannico-Romanae . Further excavations took place from 1925, 1956 to 1962 and in the following years.

History of the villa

A first simple structure made of wood was erected at the end of the first century AD. Numerous ceramics in particular originate from this period. Little of the architecture has been preserved; it consists of a few post holes, trenches and pits. Maybe it was a building with a peristyle. Remnants of wall paintings that were found under room 40 belong to this phase. They show grapes and pomegranates. Gold was found on a fragment. This is extremely rare in Britain and indicates that in the first phase extremely wealthy people lived in the villa. It was not until the middle of the third century that this house was replaced by a first stone building. It was a rectangular building with five rooms in a row. A short time later this building received a portico , hypocausts and side wings. At least one room received a mosaic. In the third construction phase, a north and south wing were added. This phase dates to the end of the third or the beginning of the fourth century. A first bath was built. In the fourth construction phase, which is dated to the fourth century, the building was again greatly expanded. The building, which previously consisted of three wings, was given an east wing, making the building a rectangle with a large inner courtyard. Numerous mosaics were laid out and other rooms were given hypocausts. The end of the villa is uncertain. The last coins to be found in large numbers date from AD 350 to 360. Only four coins can be dated later. It is a minted by Valentinian I (364–367), a coin belonging to either Valentinian or Theodosius, and two coins minted between 388 and 395. There was also hardly any pottery dating to the late fourth century. Construction was likely abandoned in the fifth century.

Mosaics

The number of figurative mosaics and their quality are unique in Roman Britain. One group of mosaics in particular, which was found in the northern part of the villa, is so stylistically and technically uniform that the individual mosaics most likely come from the same artist. Comparisons for certain motives are more common in Gaul than in Britain. The representation of Ganymede has not yet been documented in Britain.

The oldest preserved mosaic of the villa comes from room 33. It belongs to the second phase of the villa's construction and at that time it adorned the northernmost room of the complex, which was located in a risalit that was in front of the building. The mosaic probably dates to the second half of the third century. The center is a now heavily damaged head of Medusa. It was said to have protective powers against evil spirits, so that it formed a popular motif. The head is framed by three circles. In the extreme there are pictures of a dolphin, a fish and two birds. In the four corners of the mosaic are the busts of the four seasons. The mosaic is artistically rather modest. Most of the figures are drawn with black stones on a light background.

The most famous mosaic of the villa depicts Zeus as an eagle and Ganymede . It was discovered in 1811 and adorned a two-part room (approx. 9.9 × 9.2 m), which may have been used as a triclinium . The mosaic consists of two parts. In addition to the field with the Ganymede, there are six hexagonal fields, each with a dancer, maybe they are maenads. In the middle of this section there is a stone water basin. The eponymous part of the mosaic consists of the central field, in which the image of Ganymede and the eagle is located within various circles. The center of the moasik is framed on both sides by two panels showing geometric patterns.

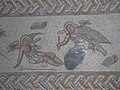

Another well-known mosaic depicts erotes as gladiators and the head of a woman, perhaps Venus . The head is in the semicircle on the north side of the mosaic. The center of the mosaic is no longer preserved today and at some point fell into the hypocaust below. It was found in a heated room with an apse, which may have been a winter dining room. The gladiator frieze consists of five scenes. A total of 12 erotes are shown, nine of them are dressed as gladiators, three of them are shown as trainers ( laniistae ). Four scenes are shown that may represent a story. The first episode shows the two gladiators fighting while the trainer watches them. In the second group, a gladiator falls to the ground. The trainer comes to help. In the third group, both gladiators rest, one of them leaning on his shield. Another figure is probably holding the helmet to equip the gladiator. The other gladiator holds a net and is guided by the trainer. The last episode shows the end of the fight. A gladiator lies on the ground and is bleeding.

In room 26 (12.30 × 5.70 m) the remains of a large two-part mosaic were found, which, however, had already been very destroyed. The northern part of the mosaic consists of four octagons at the corners of the floor, in the middle of which were the representations of the four seasons. Only the representation of winter is preserved. There must have been a central octagon in the center of the mosaic, but it was completely destroyed. The southern part of the floor had an oval in each of the four corners with the representation of erotes, only one is preserved in the drawing that was made after the uncovering of the mosaic. Another field still preserved today shows a dolphin. The short inscription TER has been preserved in a small field. This gave rise to various speculations and was interpreted as an artist's abbreviation. But it could also be part of a longer inscription.

The room with this mosaic was located on a 67-meter-long corridor, which is still decorated to 25 meters with a geometric mosaic that was excavated in 1975. Another mosaic shows a Medusa and a dolphin. There are also extensive remains of wall paintings, some of which are imitation mosaics. In the villa there were stucco work that was painted and copied marble decorations, as well as limestone slabs decorated with geometric patterns.

A well-preserved mosaic is in room 56, which was the apodyterium (changing room) of the bathroom in the south of the villa complex. The mosaic is multi-colored and shows interlocking squares that frame circles. The center of the mosaic forms a circle with the head of Medusa. The mosaic is of high craftsmanship and artistic quality, but certainly not by the same artist of the other mosaics.

literature

- Fred Aldsworth, Thomas R. Tupper (preface): Bignor Roman Villa, Guidebook (undated, approx. 1986)

- Fred Aldsworth: Excavations at Bignor Roman villa, West Sussex 1985-90. In: Sussex Archaeological Collections 133, 1995, pp. 103-188.

- Sheppard S. Frere : BIGNOR Sussex, England . In: Richard Stillwell et al. a. (Ed.): The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1976, ISBN 0-691-03542-3 .

- Sam Lysons: An Account of the remains of a Roman villa at Bignor, in the county of Sussex, in the year 1811 and the four following years , London 1815 digitized and google books [1]

- David S. Neal, Stephen R. Cosh: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume III: South-East Britain, Part 2 , London 2009, ISBN 978-085431-289-4 , pp. 489-513.

- David Rudling, Miles Russell: Bignor Roman Villa , Stroud 2015, ISBN 9780750961554 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Rudling, Russell: Bignor Roman Villa , 86–87

- ^ Rudling, Russell: Bignor Roman Villa , 63

- ^ Rudling, Russell: Bignor Roman Villa , 150

- ^ Neal, Cosh: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume III , 492

- ^ Rudling, Russell: Bignor Roman Villa , 54–57

- ↑ Rudling, Russell: Bignor Roman Villa , 32–39

- ^ Neal, Cosh: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume III , p. 496

- ^ Neal, Cosh: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume III , 506-509

- ^ Joan Liversidge: In: Albert Lionel Frederick Rivet (Ed.): The Roman Villa of Britain , Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1969, p. 131 Fig. 4.1 bc.

- ↑ Rudling, Russell: Bignor Roman Villa , 59–61

Web links

Coordinates: 50 ° 55 ′ 13.8 " N , 0 ° 35 ′ 49.6" W.