Salamander (ritual)

The salamander (also known as Schoppensalamander ) is a particularly celebratory form of drinking that is common in student associations as part of the academic drinking culture . A fixed component is rubbing the glasses on the table before and / or after drinking together. This ritual is practiced mainly in pubs and Kommersen when the old boys or High ladies are welcomed representatives of friendly connections or special guests. As part of a foundation festival , a salamander can also be rubbed to honor one's connection.

history

There are a multitude of colorful and curious explanations about the genesis of the salamander. It has been proven that salamanders according to ancient and medieval ideas - formulated by Paracelsus - belong to the elemental beings and live in the element fire . In the literature there are also several references to the salamander, a drinking ritual with burning schnapps that probably appeared in the 18th century. Later it is topped with beer.

The audible placement of the glasses comes from a Masonic custom to drink on the table , where people drink healthily. In order to avoid glass breakage, a special drinking vessel shape with a reinforced glass bottom, the so-called “cannon”, was created around the Freemasons.

After FA lights field of Salamander had its roots not in Greek or Germanic antiquity (Theocritus, Viktor von Scheffel), either at the Bonn University Richter Friedrich von Salomon (as z. B. in the questionnaire by Ernst von Salomon runs) still in the old craft or Freemason customs, but with the Saxon-Prussians in Heidelberg, namely in the shortening of their wish “Everyone drinks together!”.

The wish can also be found in the General Reichskommersbuch from 1875: That was once in the tavern / Zum Faß in Heidelberg; / It sips the god drinks / The giant like a dwarf / The praeses said: "Selbander / Shouldn't you drink today, / Everyone drinks together! ”/ And so it happened according to duty.

execution

A salamander is "rubbed" on command. To do this, all participants stand up and drink their glass of beer at the command “ ad exercitium salamandri ” (German: “to perform the salamander”) with the shout “ cheers ”. The further procedure depends on the location and connection. What they have in common is that after they have finished drinking (as completely as possible), the glasses are rubbed or rattled together on the table and placed on the table in a clearly audible manner (once or three times) on a specific command.

The special effect of the process arises from the loud noise of the clatter, the short loud thump of the simultaneous setting down of the glasses and the resulting moment of complete silence. This effect is only brought about with coordinated behavior of all those involved and is considered an expression of the community feeling of the drinkers and the appreciation for the welcomed. As a rule, those who are greeted in this way also return the favor with the hosts with a pint of salamander.

With the “Flemish” salamander, before the actual execution, an sometimes extremely long announcement is made about the effects of the “original” salamander, before the participants are finally allowed to drink.

In Austria mainly a special form of salamander, the so-called "festival salamander", is grated, which is used purely to honor members.

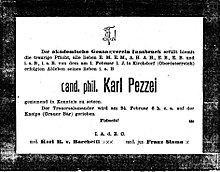

Mourning salamander

The mourning salamander , also known as the dead salamander in Switzerland, has become rare . He honors a particularly esteemed brother, with some connections in Austria and Switzerland every deceased federal brother. The senior commands: “Ad exercitium salamandri in honorem et pro laude after our dear deceased… 1-2-3 bibite ex”. Everyone empties their glass, but does not put it down, but "rubs" the salamander over the table. In some places the senior throws his glass on the floor as a sign that the dead will never drink from this glass again and wishes "fiducit".

In the corps it was customary to sing the song Vom hoh'n Olymp down after the silent salamander .

Knot salamander

In the GDR , students interested in color, partly out of ignorance of the student tradition, developed the independent form of the knotted salamander from the honor salamander . This was done several times on the occasion of a salamander bar. Some connections denied the entire process of a pub with knotted salamanders , again due to a lack of knowledge of traditional pub forms. Each participant was given a beer cord (approx. 30 cm long). After each knotted salamander, a knot was tied into the beer cord. For some couleur students, the beer cords were turned into frets, which were worn on the belt in place of traditional tips . Even today some of the members of the Rudelsburg Alliance still celebrate salamander bars. With many old connections in particular, however, this new bar form is viewed as the new high point of the Pennälercomment and is more for amusement.

literature

- Erich Bauer : Our salamander. An overview of the main explanations. In: then and now. 5, 1960, pp. 142-155.

- AJ Uhrig: De exercitio salamandri. Wuerzburg 1885.

- Friedhelm Golücke : Student Dictionary . Graz, Vienna, Cologne 1987 p. 378ff.

- Robert Paschke : Student History Lexicon. GDS archive Volume 9, Cologne 1999 p. 227f.

Web links

- Beer salamander at Saxo-Borussia (PDF file; 120 kB)

- Ad exercitium salamandri! Scene from Der Untertan , a DEFA film based on the novel by Heinrich Mann, performing an honor salamander

Individual evidence

- ↑ Westermann's illustrated German monthly books , January 1875 and June 1876

- ↑ Ernst von Salomon : The questionnaire ; European Book Club; Stuttgart, Zurich, Salzburg 1951; P. 89f

- ^ Siegfried Schindelmeiser: The Albertina and its students 1544 to WS 1850/51 and the history of the Corps Baltia II zu Königsberg i. Pr. (1970-1985). For the first time complete, illustrated and annotated new edition in two volumes with an appendix, two registers and a foreword by Franz-Friedrich Prinz von Preussen, ed. by Rüdiger Döhler and Georg von Klitzing, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-00-028704-6 , p. 315