Egeregg Castle

The abandoned Egeregg Castle was located below Lederergasse 22 and 24 on the former Ludlarm in Linz . The Pruner monastery was later built on the property .

history

Koloman Egerer was a Viennese citizen and trader. In 1551 he acquired a plot of land from the Widem farm on the Ludl , which belonged to the city parsonage, for his trading business in Linz . This area was outside the city's jurisdiction and was not in great demand due to the risk of flooding and swamp. The Ludl in Linz was a right side branch of the Danube in the area of today's Eisenbahn- und Ledererstraße, which flowed back into the main stream at the tobacco factory site. Since the Ludl was very watery, businesses that needed a lot of water settled here (for example the “Lederer”). Between the Ludl and the main stream lay the Werd or Wörth, a swampy meadow area. Due to a flood in 1572, the Danube created a new tributary, which drew a lot of water from the Ludl, so that it gradually silted up and only existed as a weak ditch. In 1892 it disappeared completely due to the canalization of Linz; today only the street name Ludl has survived, but most people in Linz have no use.

After purchasing the site, Egerer erected a building here, which was expanded in 1564. After his families he named the house in a romanticizing way and in the desire for an ennoblement Egereck. In 1572 Kolomann Egerer was actually elevated to the nobility by Emperor Maximilian II . At the same time he received an imperial charter, which included the elevation of the Linz house Egereck to a free house. This was also related to the fact that Egerer was exempted from basic service and the tax burdens to the Linzer Stadtpfarramt and the sovereign princes, albeit against the deposit of a sum of money, the interest of which was used to pay the future burdens. Koloman's will is dated 1587 and suggests that he died around that time. The Egerer family at that time consisted of the widow Katharina Rottin, the daughter Anna, the sisters Barbara (married host), Magdalena (wife of David Lang), Christina (married in first marriage to the humanist Johannes Sambuky [also written Johann Sambucus ], in second marriage to Wolfgang Sinich [Synich]) and the brothers Jakob and Sebastian. The male line of the Egerer family is likely to have died out as early as 1598, because this year Emperor Rudolf II awarded the coat of arms of Sebastian Egerer to the already ennobled court servant Hans Gastgeb (who was married to the aforementioned sister Barbara of Koloman Egerer) . It is also worth mentioning the will of Christina Egerer, who obviously - like her husband Sambucus - had to be attributed to the Protestants on the basis of a certificate made .

Probably because of a will that no longer exists today, Egereck came to Pernhart (Bernhart) von Puchheim towards the end of the 16th century. He sold the property to Michael Pittersdorfer von Freyhof in 1610. On the basis of a purchase contract from 1615, the Freihaus then came to Christoph Hohenfelder auf Peuerbach ; At that time he also owned Almegg , Aistersheim , Reichenstein , Weidenholz and Wildenstein . Although the Hohenfelder already had several possessions in the area around Linz (for example a Hube and other farm shares in Bergham , also the so-called Hechenfeld Office of the Ebelsberg lordship ) the Freihaus was sold to Constantin Grundemann von Falkenberg in 1622; in 1630 the possessions were also transferred to Linz and the surrounding area sold to Grundemann.

Constantin Grundemann was the toll collector in the countries above and below the Enns and took an active part in the Counter-Reformation . Through this position and the "right faith" the Grundemanns rose to the favorites of the emperor. This rise went hand in hand with the purchase of further rulers (for example, the rulership of Streitwiesen in Weitental in 1626 and the rule of Waldenfels near Reichenthal in 1636 ). Constantin Grundemann († 1658) was married to Cäzilia Alt von Altenau, daughter of Salzburg Archbishop Wolf Dietrich von Raitenau and his wife Salome Alt . He was succeeded by his son Georg Constantin († 1692). Since his children died early, he determined in his will of 1688 the rule of Waldenfels to a Fideikommiss , which first passed to his nephew Ernst Constantin. 1695 came to the Fideikommiss Waldenfels also the subjects of the free seat Egereck. The Grundemanns rose further in the aristocratic hierarchy, so Ernst Constantin was accepted into the baron class in 1696 and his son Johann Adam († 1719) was raised to the imperial count status in 1716.

Under the Grundemanns, the Freihaus Egereck was tacitly (ie without the explicit consent of the sovereign or pastor) the Egereck open space. The patio was partially designated as the place of residence of the widow of Constantin Grundemann Susanna Catharina (née von Grubegg); In addition, the castle was used as a temporary residence for the Grundemann family when they were in Linz. The goods belonging to the Freihaus were administered by the Egereck Office.

In 1718 Egereck was sold to the imperial court war councilor Anselm Franciscus Freiherr von Fleischmann. The house was downgraded to a Freihaus again and the tax privileges enjoyed by the Grundemanns were not granted to the butcher. Around 1730 Egereck is said to have been sold to Wolf Fortunat Ehrmann von Falkenau. From this in 1734 the imperial postmaster Josef Groß von Ehrenstein acquired the property. His brother-in-law, the Mayor of Linz Johann Adam Pruner , laid the foundations for the establishment of the Prunerstift in his will in 1730. A care institution for orphans and poor people should be created. In order to realize this foundation, Groß von Ehrenstein bought Egereck and had it demolished in 1737. The demolition material was used for the Prunerstift and the associated church.

Building history of Egereck

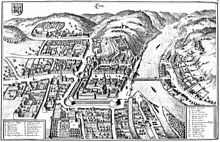

The patio was built in a square shape with four flanking onion-crowned corner turrets, as can be seen in the view of Linz by Lucas van Valckenborch (1593); Egereck is located with its corner turret on the brush drawing on the far left in the center of the picture, next to it is the Eyring patio with a tent roof and attached turret. On the engraving by Matthaeus Merian (Egeregg Castle is in the middle at the lower edge of the picture) the location towards Ludl becomes clear. Due to the shape of the Egereck house, old fortifications were imitated without the building itself being a fortification. The real estate, which was still very modest under Koloman Egerer, was expanded, especially by the Grundemanns, to a considerable free float in and around Linz, in the Mühlviertel and in the Traunviertel. The superintendent of the Egereck possessions was exercised by the keeper of Waldenfels, however the Egereck possessions listed in a land register were assigned to an independent Egereck office.

After the purchase of the castle and the associated meadows for the Pruner monastery, demolition began immediately in 1734. However, since there was no imperial consensus for the demolition, it had to be stopped immediately (which, however, was not really the case, as the annual statements for the cost of building the Prunerstift show). The demolition of the castle was subsequently justified by the fact that the building would no longer be inhabited, the condition of the house made it impossible to live in and, moreover, that it was located on a secluded property by the foul-smelling Ludl. In 1737, the imperial approval for the demolition was given.

The basement floors of Egereck were preserved for a long time and served as underground stables. During the construction of the horse-drawn railway from Linz to Gmunden and a planned connection point to Urfahr via Lederergasse - ownership of this part of the Prunerstiftung passed to Prince Schwarzenberg in 1795 - the last remains of the open space were removed.

The palace area has now completely disappeared due to a modern overbuilding with residential buildings.

literature

- Norbert Grabherr: Castles and palaces in Upper Austria. A guide for castle hikers and friends of home. 3rd edition . Oberösterreichischer Landesverlag, Linz 1976, ISBN 3-85214-157-5 .

- Georg Grüll: Castles and palaces in Upper Austria, Volume 2: Innviertel and Alpine foothills . Birken-Verlag, Vienna 1964.

- Franz Wilflingseder : History of the former Egereck outdoor seating in Linz, Yearbook of the City of Linz 1954, pp. 455–484 . City of Linz, Linz 1955.

Individual evidence

- ↑ ERNST NEWEKLOWSKY: THE DANUBE NEAR LINZ AND ITS REGULATIONS (PDF file; 3.51 MB)

Coordinates: 48 ° 18 ′ 24.3 " N , 14 ° 17 ′ 31.6" E