Battle of Preveza

| date | September 28, 1538 |

|---|---|

| place | near Preveza , Ionian Sea |

| output | significant victory of the Ottoman fleet |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Holy League : Republic of Venice Spain Papal States Republic of Genoa Order of Malta |

|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 162 galleys, 140 barges, approx. 60,000 soldiers |

122 galleys, approx.20,000 soldiers |

| losses | |

|

13 ships sunk / destroyed, |

no ship losses, |

The sea battle of Preveza took place on September 28, 1538 off the coast near Preveza in north-west Greece between a fleet of the Ottoman Empire and that of a Christian alliance, Pope Paul III. had brought about instead.

prehistory

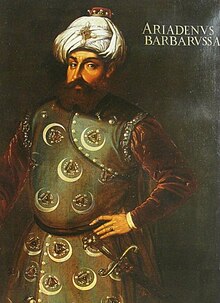

Khair ad-Din Barbarossa , the commander of the Ottoman fleet , appeared in the Ionian Sea in 1537 , besieged the Venetian fortress of Corfu and devastated the coast of Calabria in southern Italy.

Faced with this threat, Pope Paul III worried. in February 1538 to form a Holy League in which armed forces of the Pope, Spain and Venice should stand up to Barbarossa's fleet. Its squadron comprised a total of 122 large and small galleys in the summer. The mobilized fleet of the Holy League consisted of 302 ships (162 galleys and 140 barques), of which 55 galleys were provided by the Republic of Venice, 49 by Spain and 27 by the Papal States and the Order of St. John . Andrea Doria , the Genoese admiral in the service of Emperor Charles V , was in command.

Course of the battle

The members of the Holy League decided to unite their fleets at the island of Corfu. First arrived the papal fleet under the command of Marco Grimani and the Venetian fleet under the command of Vittore Capello. On September 22, 1538, the Spanish-Genoese fleet under Andrea Doria joined the war armada.

Before Andrea Doria's arrival, Grimani attempted to land troops near the fortress of Preveza, but withdrew them when he suffered several losses in clash with Ottoman forces.

Barbarossa was at that time on the island of Kos in the Aegean Sea , but appeared soon after an attack on the island of Kefalonia with the rest of the Ottoman fleet at Preveza. Sinan Reis, an elderly Turkish general who resented the command of Barbarossa, urged him to land troops at Actium on the Gulf of Arta near Preveza. Barbarossa disliked this plan, but reluctantly agreed to it at the urging of his soldiers and their leaders. The attempt to secure the position on land failed when the troops led by Murat Reis came under massive fire from Christian ships and had to retreat to their ships.

Since the Ottomans held the fortress at Actium and were able to support Barbarossa's fleet from there, Andrea Doria had to keep his ships off the coast. A landing to take Actium would probably have been necessary to ensure success. But Doria feared defeat on land after the initial attempt by Grimani was repulsed by Ottoman forces before his arrival.

Although the Christian ships tried to keep their distance from the coast, they drove adverse winds towards the enemy shore and Barbarossa had the more advantageous interior position. On the night of September 27-28, Doria sailed 30 miles south, and when the wind died down he anchored at Sessola near the island of Lefkada . During the night Doria and his commanders decided that the best option would be to stage an attack in the direction of Lepanto and force Barbarossa to fight.

At dawn, however, Doria was surprised to see the Ottomans sailing in his direction. Barbarossa's fleet of now around 140 ships had left their anchorage and was heading south. Turgut Reis formed the vanguard with six large ships, and the left wing came close to the coast. Not expecting such a daring offensive from the outnumbered Turkish fleet, it took Doria, urged by Grimani and the Patriarch of Aquileia , Vincenzo Capello, three hours to order his fleet to lift anchor and be ready for action.

The lack of wind was unfavorable for Doria. The very large Venetian flagship " Galeone Di Venezia " with its massive cannons was stuck in a slack four miles from land and ten miles from Sessola. As the Christian ships struggled to get close to stronger support, they were soon surrounded by enemy galleys and embroiled in a furious battle that lasted hours and caused much damage to Ottoman galleys.

When the wind came up, the rest of the Christian fleet eventually drew nearer, although Doria first had a number of maneuvers carried out to lure the Ottomans out to sea. Ferrante I. Gonzaga , the Viceroy of Sicily , acted on the left wing of the combined fleet, while the Maltese Knights formed the right wing. Doria placed four of his fastest galleys under the command of his nephew Giovanni Andrea Doria and positioned them in the middle of the fleet. The papal and Venetian galleys were positioned behind it. The final part was formed by the Venetian ships under the command of Alessandro Bondumier and the Genoese ships under the command of Francesco Doria.

Barbarossa's chief officers, Turgut Reis, Salih Reis, Murat Reis and Güzelce Kaptan, commanded the wings of his fleet and involved the Venetian, papal and Maltese ships in battle. Doria herself hesitated to act with his center against Barbarossa, which led to all kinds of tactical maneuvers, but little fighting. At the end of the day, the disciplined fighting Ottomans had captured or sunk a considerable number of Christian ships. The following morning, with a favorable wind, Doria set sail and left the battlefield for Corfu - unwilling to risk the Spanish-Genoese ships and deaf to objections from the Venetian, papal and Maltese commanders to continue the fight.

In the end, the Ottoman side had about 400 dead and 800 wounded, but lost no ships. The Ottomans sank two Venetian galleys, a papal galley, and five Spanish ships carrying soldiers (many of whom were captured), set fire to five merchant ships from Venice and Ragusa , captured 36 Christian ships, and captured around 3,000 people in total.

Evaluation and consequences

The victory of the Ottomans in this battle formed the basis for the fact that the Ottoman Empire was the leading sea power in the Mediterranean for a few decades until the naval battle of Lepanto in 1571 . Some historians believe that the victory before Preveza was the greatest achievement in Ottoman naval history.

It is often speculated that Doria's excuses and lack of zeal were due to his reluctance to risk his own ships (he personally owned a significant number of the “Spanish-Genoese” fleet) and his longstanding hostility to Venice, the fierce one Rival of his hometown and primary target of Ottoman attacks at the time.

In 1539, Barbarossa returned and captured almost all of the remaining Christian outposts in the Ionian and Aegean Seas.

In October 1540, a peace treaty was signed between Venice and the Ottoman Empire, which allowed the Ottomans to control the Venetian possessions in Morea and Dalmatia and the Venetian islands in the Aegean, Ionian and eastern Adriatic Seas . Venice also had to pay tribute to the Ottoman Empire with 300,000 gold ducats .

With the victory in the Battle of Preveza in 1538 and the Naval Battle of Djerba in 1560, the Ottoman Empire successfully fended off the efforts of the two Mediterranean powers Venice and Spain to halt the continued Ottoman drive to rule the Mediterranean. This only changed with the naval battle of Lepanto in 1571.

literature

- Michael A. Cook (Ed.): A History of the Ottoman Empire to 1730. Chapters from the "Cambridge history of Islam" and the "New Cambridge modern history" from Vernon J. Parry . CUP, Cambridge 1976, ISBN 0-521-20891-2 .

- Edward H. Currey: Sea-Wolves of the Mediterranean . John Murray, London 1910.

- John B. Wolf: The Barbary Coast. Algeria under the Turks . WW Norton, New York 1979, ISBN 0-393-01205-0 .