Seppuku

|

|

This article is about suicide. For those at risk, there is a wide network of offers of help in which ways out are shown. In acute emergencies, the telephone counseling and the European emergency number 112 can be reached continuously and free of charge. After an initial crisis intervention , qualified referrals can be made to suitable counseling centers on request. |

Seppuku ( Jap. 切腹 ) refers to a ritualized nature of male suicide that from about the mid-12th century in Japan within the layer of the Samurai was widespread and was officially banned. 1868

A man who lost face for a breach of duty was able to restore his family's honor through Seppuku. Other reasons for seppuku were among other penalty for a violation of law or the so-called oibara ( 追腹 ) where ronin (masterless samurai) that their daimyo , this was followed by the death had lost (local lords in feudal Japan) if he allowed them in writing.

The term Harakiri ( 腹切り from 腹 hara "belly" and 切る kiru "cut" - reverse order of Kanji -special) is used mainly in Europe and America.

Other names were Kappuku ( 割 腹 , “slicing the belly”), Tofuku ( 屠 腹 , “slaughtering the belly”), Isame Fuku ( 諫 腹 , German about “suicide in protest [against a decision]”), Junshi ( 殉 死 , "Follow into death") for followers who followed their master into death, as well as keikei ( 閨 刑 , "bedroom punishment ") for the court nobility .

procedure

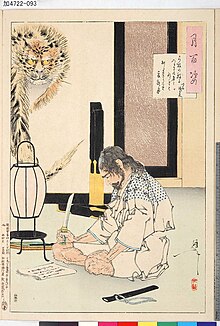

During the seppuku, the man sitting in the seiza , after exposing his upper body, usually cut his stomach about six centimeters below the navel, usually from the left, with the blade of a wakizashi (short sword) or tantō (dagger) wrapped in paper and mostly kept specially for the occasion on the right with a final upward guide of the blade. According to Daoism , this is where the so-called lower tanden (Chinese: Dantian ), an area in the hara ( lower abdomen ), which is regarded as the most important energetic center of humans in traditional Chinese medicine , and also the main artery of ki in Zen .

Since the abdominal part of the aorta (main artery) lies immediately in front of the spine, the vein was usually cut or completely severed, and the immediate drop in blood pressure resulted in a loss of consciousness within a very short time. However, alternative cuts and additions have also been used over time. For example, there are descriptions of a so-called jūmonji-giri , a technique that was temporarily preferred by the daimyo, which actually consisted of two cuts and accelerated the emergence of the internal organs through its cross shape.

After the cuts had been made, a standing assistant (the kaishaku-nin or second, also a samurai, mostly the closest confidante) , before or after the setting down of the blade, largely opened the neck with a katana or less often with a tachi from the cervical spine, however not completely severed for quick death. The second had previously stood out of sight of the death row inmate and waited for the right time. The redeeming blow had to be carried out with absolute conscientiousness in order not to prolong the suffering unnecessarily through a delayed execution. Had it been applied prematurely, i.e. before the head was bent, the blade would have got stuck in the cervical vertebrae and would have required additional blows in addition to further agony. The second also had to make sure that the head was not completely separated from the trunk, which still had to be connected to the body by a skin flap. Anything else would not have been respectful of the candidate and would have been more reminiscent of the execution of a criminal. Because of all these factors, there was a great deal of responsibility on the assistant's shoulders. It happened that a bad kaishaku-nin was asked to seppuku himself.

The above-mentioned high demands on the Kaishaku-nin were later relaxed, as the art of swords was mastered by fewer and fewer men at this high level. A complete severing of the head was therefore recognized later (around the 18th century).

The service of the kaishaku-nin was of great importance to the dying: a samurai was not allowed to grimace, sigh, groan, or even show fear during seppuku. As soon as the personal pain threshold had been reached, he bowed his head slightly and received the fatal blow. About the behavior of the person committing Seppuku in the decisive moments, a written evaluation was made by the attendees, which decided whether the ritual was recognized as an official Seppuku due to correct execution and dignified behavior.

It was not objectionable for a samurai to bend the head forward before the technique was completed or after the puncture. It was crucial that the family and loved ones, when looking at the head afterwards, could not see any pain in the facial expression of the killed person. Therefore, it was often considered an official seppuku if the fatal blow was carried out as soon as the main character even reached for the blade. For example, samurai who were not trusted to perform abdominal cuts were later replaced with a fan or a branch of the sacred bulky bush .

The cutting technique of the second is included in the seventh kata of the Seiza forms of various sword fighting schools. In the Musō Jikiden Eishin Ryū she is called Seiza Nanahomme Kaishaku , in the Musō Shinden Ryū she is taught under the name Junto (Kaishaku) . It is only practiced, but not shown during exams or for demonstration purposes.

All about the ritual

Seppuku was reserved for the samurai. Priests, farmers, artisans or traders were not allowed to do it because it was believed that they could not endure the great pain.

The actual suicide ceremony has been changed over and over again over several centuries, with minor regional differences emerging. An official Seppuku with a nin Kaishaku- but were at least wearing white clothing as a symbol of spiritual purity (which come by opening the abdomen to light should), the presence of a Shinto -Priesters and a note-taker , taking one last Meal and writing a death poem (usually in the form of a haiku ). The ritual was mostly carried out in the garden of one's own property, in front of the local Shinto shrine (but outside the access gates and therefore not on consecrated ground) or in a specially designed place at the court of the respective prince. Seppuku within a building for which special tatami (rice straw mats) with a white border were made, which were disposed of after the ceremony and the burning and burial of the samurai , are less common .

Samurai were usually given between two and six months to prepare their seppuku. It is not known whether there were any samurai who attempted escape during this period, as no such case has ever been documented. Since a samurai could not be held captive by his own clan, officials were only sent occasionally and at longer intervals to inquire about the mental and physical condition of the contemplative person. In the case of a prisoner of war there was a shortened version of the seppuku ritual.

Women also sometimes committed ritualized suicide, but this was referred to by the generic term jigai ( 自 害 ). They pricked their jugular vein with a hairpin or a kaiken . In order to avoid dishonor, the legs were tied together with a ribbon made of leather or silk in order to prevent the legs from spreading in agony.

Occasions for Seppuku

The samurai practiced seppuku mainly for four reasons: First, it avoided shame if one fell into the hands of the enemy during a battle and became a prisoner of war . Furthermore, it could be carried out at the death of the master ( daimyo ), or one protested with the help of the seppuku against a mistaken superior. After all, it was also used to carry out the death penalty .

Prohibition of the ceremony

With the beginning of the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Seppuku was generally banned in Japan. Due to the surrender of Japan in the Pacific War , declared by Emperor Hirohito on August 15, 1945, and the associated loss of honor of the Japanese people, many feared that the emperor would, despite the ban, encourage members of the military to do seppuku, which he ultimately did not. However, high military officials like the Minister of the Army Anami Korechika did it voluntarily.

The last officially known ritual seppuku was performed by the Japanese writer Mishima Yukio . On November 25, 1970 in Tokyo , after a general of the Japanese armed forces had been taken hostage and a subversive appeal to the stationed soldiers, in the presence of members of his private army, he committed seppuku and was beheaded by a confidante.

Famous people who died by seppuku (selection, sorted by date of death)

- Minamoto no Yorimasa (Army leader, 1106–1180)

- Minamoto no Yoshitsune (General, 1159–1189)

- Kusunoki Masashige (Japanese national hero, 1294-1336)

- Oda Nobunaga ( Daimyō , 1534–1582)

- Shibata Katsuie (general, 1522–1583)

- Hōjō Ujimasa (head of the later Hōjō, 1538–1590)

- Sen no Rikyū (high-ranking tea master, 1522–1591)

- Torii Mototada (Samurai, 1539–1600)

- Asano Naganori ( Daimyō , 1667–1701)

- The 47 Rōnin (abandoned samurai of Asano Naganori , February 4, 1703)

- Yamanami Keisuke (Samurai, 1833-1865)

- Nogi Maresuke (General, 1849–1912)

- Tadamichi Kuribayashi ((probably) commander of the Japanese army on Iwojima , 1891–1945)

- Anami Korechika (Minister of War, 1887–1945)

- Ōnishi Takijirō (Admiral, 1891–1945), founder of the Japanese kamikaze units

- Mishima Yukio (writer, 1925-1970)

Movie

In the film adaptation of the novel Shogun , a seppuku is reproduced in detail. In 1962, Japanese director Masaki Kobayashi made a film called Seppuku . The film paints a critical picture of feudal Japan in the 17th century and its central theme is the planned and ultimately also carried out suicide of a samurai.

The ritual suicide committed by the title character in Mishima - A Life in Four Chapters (1985) is based on a real event . In a multi-layered film biography, the American author and director Paul Schrader tells of the career of the Japanese writer and political activist Mishima Yukio. The film ends with Mishima's suicide, but only the beginning is shown.

In 1966, Mishima himself had shown a seppuku in detail in his short film Yûkoku ( 憂国) , which was based on his story of the same name (German patriotism ). In it, a Japanese lieutenant and his wife commit suicide after a failed coup attempt.

Another film on the same topic is The Hidden Sword . It is about a samurai who is asked to do seppuku in order to avoid the shame of an execution. The resulting internal and external struggle and the complicated relationship between two friendly samurai, shaped by norms and formalities, determine the plot of the film.

In the film Last Samurai , one of the main characters also ends his life with a seppuku after being badly wounded in a fight that is believed to be lost.

The Japanese-English film Hara-Kiri - Death of a Samurai , Japanese Ichimei (一 命) , by the director Takashi Miike from 2011 deals with the ritual and the situation of the Rōnin in the 17th century. It is a remake of the material from the 1962 film Harakiri .

In the US film 47 Ronin (2013), Seppuku and the ritual associated with it are shown in detail several times.

literature

- Maurice Pinguet : Suicide in Japan. History of Japanese Culture . Translated from the French by Makoto Ozaki , Beate von der Osten and Walther Fekl. Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-8218-0637-0 .

- Yamamoto Tsunetomo : Hagakure - The Book of the Samurai . Bechtermünz, 2001, ISBN 3-8289-4870-7 .

- Francesca Di Marco: Suicide in Twentieth-Century Japan . Routledge, Mellon Park, Abingdon, Oxon, England 2016, ISBN 978-1-138-93776-5 .

Web links

- Historical Samurai Archives (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Uemon Moridan: Seppuku: Etiquette for Seppukunin, Kenshi & Kaishakunin . 2016, ISBN 978-1-5234-8692-2 .

- ↑ Lafcadio Hearn Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation 1923 reprint 2005 Page 318 "Among samurai women - taught to consider their husbands as their lords, in the feudal meaning of the term - it was held a moral obligation to perform jigai by way of .. "

- ↑ 築島謙三Tsukishima Kenzo translator and editorラフカディオ·ハーンの日本観:その正しい理解への試み(Lafcadio Hearn's Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation) 1984 Page 48 "いろいろその機能に変化が生じてきたけれども,この切腹,自害は上代日本の宗教的の証拠と考えるとすれば,それは大きな誤まりであって,むしろこのような行為は由来宗教的な性格をもこのような自己犠牲をテ-マにした悲劇を日本の国民 は い ま な お 愛好 し ... "

- ^ Joshua S. Mostow Iron Butterfly Cio-Cio-San and Japanese Imperialism - essay in A Vision of the Orient: Texts, Intertexts, And Contexts of Madame Butterfly editor JL Wisenthal 2006 - Page 190 "Lafcadio Hearn, in his Japan: An Interpretation of 1904, wrote of 'The Religion of Loyalty': In the early ages it appears to have been… jigai [lit., 'self-harm,' but taken by Hearn to mean the female equivalent of seppuku], byway of protest against ... "