Widow burning

Widow burning , also known as sati , is a femicide in Hindu religious communities in which women are burned. Widow burnings have so far been most common in India , but they also occurred in Bali and Nepal . In the event of a widow cremation in India, the widow burns at the stake together with the body of the husband ( widow succession ). Some of the women who previously cremated together with the corpse of their husbands were held in high honor after their death and in some cases were worshiped divinely; her family gained high esteem. Originally, the women of the men from royal families who had fallen in battle killed themselves in this way, possibly so as not to fall into the hands of the enemy. Widow burning, initially thought of as suicide , has been called for in many sections of the population over time. Widow burning was particularly common among the Kshatriya castes, such as the Rajputs in northern India, where it still occurs today.

etymology

The term sati comes from Sanskrit . It is the feminine derivation of the participle form “sat”, which means “being” or “true” and denotes something morally good. Accordingly, “sati” is a “good woman”. Since a good woman is loyal to her husband in the classical Hindu understanding, “sati” also means “faithful woman”. Because in Hinduism a person is only considered dead after cremation, "sati" and widow can also be viewed as mutually exclusive categories - until the cremation it is not a question of a widow, but rather of the wife.

Sati is also the name of the goddess Sati .

procedure

If a man dies, his body will be cremated within a day. The widow usually has to decide to burn the widow shortly after the loss of her husband in order to become a religiously legitimized Sati and to enable the marriage to be resumed quickly after death. The continuing bond is symbolized by the fact that the woman is treated like a wife and not like a widow until the end.

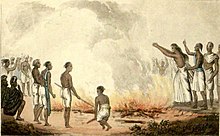

After the decision, an elaborate ceremony was previously prepared, which differed depending on the region, but in which priests were always involved. In addition, accompanying musicians, decorated robes and gifts were common. Most of the time, the widow died by burning at the stake . It was seldom buried alive . There were also killings through the use of weapons or violence if the woman resisted the cremation and fled.

The widow was at the stake with the man's body, and the eldest son or the closest male relative lit the fire.

Means of preventing the widow from escaping due to fear of death were spilling with large pieces of wood or holding down with long bamboo sticks. An expanded form that was common in central India is the erection of a hut-like structure at the stake. The entrance was closed with wood and barricaded and the hut, which was weighed down with more wood, was brought to collapse shortly after the fire was ignited. In southern India there was another method of digging a pit. A curtain blocked the widow's view of the fire until she finally jumped in or was thrown into it. Usually heavy wooden blocks and easily combustible material were then thrown at the victim.

As soon as the woman lost consciousness, the cremation was brought to an end with chants and religious rituals.

history

In the 1st century BC, the historian Diodorus tells of a fallen Indian military leader named Keteus. Both widows of Keteus burned at the stake with their husband's body. Other ancient Greco-Roman authors also describe widow burning. It was especially widespread among the belligerent elite.

Between 700 and 1100 widow burnings became more frequent in northern India, especially in Kashmir and in noble families. In his work Rajatarangini , the Indian historian Kalhana describes cases in which concubines also burned to death after their partner died. The principle was extended to include close female relatives such as mothers, sisters, sister-in-law, and even servants. The history mentions numerous cases of widow burnings. This development can be proven archaeologically by means of memorial stones, the "sati stones". They usually show the raised right arm with a bracelet, which symbolizes the married woman. Widow burning also became increasingly popular among Brahmins . Widow burning was highly regarded in Hinduism, but not an obligation. It was mostly limited to certain regions and social classes.

Reports by Muslim authors who came to India after the Muslims conquered India date back to the Middle Ages. The Berber Ibn Battuta , who traveled to India in the 14th century, reports of widow burnings. Ibn Battuta writes that widow burning in Muslim areas of India required the permission of the Sultan , and that widow burning was considered a laudable but not compulsory act by the Indians; however, the widow was considered unfaithful if she did not burn.

Martin Wintergerst , who was in India around 1700, wrote that he had heard that widow burning was caused by the murder of men by their wives a few months after the wedding. In order to prevent such murders, widow burning was introduced.

From the end of the 16th century widow burning spread in the Rajasthan area and became more and more common among the Rajputs . After the death of a king or high noblewoman, widows who were childless and dispensable for official duties almost always followed their husbands. However, it was not mandatory, for example, the surviving women continued to receive fiefs. European travelers reported widow burnings that they had witnessed themselves. At the end of the 18th century, widow burning was so widespread that it was mandatory, at least in royal houses. It had become a collective experience, so that every person had heard of a widow burn and probably even witnessed it. However, there were also dissenting voices who considered a life of chastity more important than widow burning.

At the time of British rule , the English colonial rulers tried, after initially ignoring them, to regulate widow burning. For this purpose, individual cases were documented over a large area and statistics were created. In the Bengal Presidency , the death rate, population and the number of unreported cases resulted in a statistical average of one widow burnt to 430 widows. In a place with 5,000 inhabitants, a burn took place every 20 years. The regional differences were considerable. The rejection of widow burning by the Europeans led in 1829/1830 to the ban on burnings in the British colony, which was enforced by the movement around the Hindu reformer Ram Mohan Roy . Observing participation could already be punishable by law. As a result, widow burns became increasingly rare, and when they became known they were reported in detail in the press. In 1953, the last sati from the royal family was burned in the city of Jodhpur in Rajasthan .

Widow burning was banned in Nepal in 1920.

Widow burning today

Burns still occur, albeit less often. A well-known case is Roop Kanwar , an eighteen-year-old widow who was burned at her husband's stake in 1987 in Rajasthan. The combustion was watched by thousands of spectators and around the world through media and science rezipiert . It is debatable whether she was put to the stake with or without coercion. Thousands of supporters of the widow burning then made a pilgrimage to the place. The death of Roop Kanwar led to heated public disputes and a further tightening of the ban on widow burning.

The widow burning could not be completely stopped, however, individual cases are still known. Due to the illegality and the partially existing social acceptance, a high number of unreported cases is assumed. Estimated figures assume 40 cases in the time frame from 1947 to 1999, 28 of them in Rajasthan, possibly even more. An increase in the numbers is not expected in the last few decades.

Cases since Roop Kanwar are:

- On November 11, 1999, the 55-year-old farmer Charan Shah burned at her husband's stake in the north Indian village of Satpura.

- On August 7, 2002, 65-year-old Kuttu Bai died at the stake of her late husband in Patna Tamoli Village, Panna District , Madhya Pradesh .

- On May 18, 2006, 35-year-old Vidyawati was burned to death in the village of Rari-Bujurg, Fatehpur, in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh .

- On August 21, 2006, Janakrani, around 40 years old, died at the stake of her late husband Prem Narayan in the village of Tuslipar, Madhya Pradesh, India .

- On October 11, 2008, 75-year-old Lalmati Verma was put on the already burning stake of her husband in Kasdol, Raipur district, in the Indian state of Chhattisgarh .

- On December 13, 2014, the 70-year-old Gahwa Devi was buried in Parmania, Saharsa district in the Indian state of Bihar , 220 km from Patna, at the stake of her husband Ramcharitra Mandal, who had died at the age of 90. Villagers said that Gahwa Devi was put at her husband's stake after the family left. Still, there are no witnesses to the incident. The relatives say they returned to the pyre when they discovered that Gahwa Devi was missing. Since she was already dead, they would have added wood. Her son Ramesh Manda testified that his mother died of heart failure from grief after his father died and was subsequently cremated with the father.

- On March 28, 2015, Usha Mane was found burned near the stake of her late 55-year-old husband Tukaram Mane in the village of Lohata, Latur district in the Indian state of Maharashtra . The family testified that the woman had disappeared the night before, after the death of her husband. They did not find her body until the next day when they wanted to fetch ashes from the pyre and burned it on a second pyre. The death was recorded as an accident.

According to Indian law, any direct or indirect support for widow burning is now prohibited. The traditional glorification of such women is also punished. However, this law is not always enforced with the same vigor. The National Council for Women (NCW) recommends improvements to the law. The Ministry of Tourism of Rajasthan published a book in 2005 called Popular Deities of Rajasthan , which was criticized for positive statements about widow burnings. Rajasthan Tourism Minister Usha Punia defended the book's positive portrayal of burns, claiming sati is now seen as a source of strength.

Due to the ongoing veneration of the Satis and the tourist interest in Satis, according to women's organizations there is still the risk that widow burnings will become more frequent again for economic reasons. Roop Kanwar's burning became a commercial success with Kanwar merchandising, at least two major Kanwar events, and fundraising for a Kanwar temple that raised $ 230,000 in three months.

reasons

There are religious, political, economic and social reasons for widow burning.

Social reasons

In some sections of the population, widows were expected to self-immolate. Sometimes the grieving widows were brought to self-immolation through social pressure and sometimes also forced with violence. The Indologist Axel Michaels sees the social reasons in the system of the patrician line , in which the widow loses respect and authority. She has the problem of care, has no rights and is dependent on the eldest son. She may have to be accused of being responsible for the man's death. She must live chaste and humble; nevertheless, she could be threatened with being cast out and ending up as a beggar or a prostitute.

Hindu widows are disadvantaged because they have to shave their heads on the day the man dies, only wear clothes made of coarse white cotton and are not allowed to eat meat or take part in festivals. Many penniless Hindu widows who have been cast out by their families go to the city of Vrindavan to beg for the rest of their lives.

This bad situation is also blamed for driving widows to suicide.

Economic reasons

The English colonial official, historian and racism researcher Philip Mason writes that between the 17th and 19th centuries a particularly large number of widow burnings were carried out in colonial Bengal. According to statistics from the British colonial authorities, almost 600 women were burned there in 1824. In nine out of ten cases the women were forced to be cremated because the widows in Bengal were entitled to inherit. According to Mason, the victims were tied to the body of their husbands and men with large sticks guarded the pyre in case the injured victim was able to free himself again.

Even today it is economically advantageous for the in-laws if the widow burns to death instead of returning to her family, because when she returns she can take her dowry with her. In the event of cremation, however, the dowry remains in the possession of the in-laws.

Widow burnings still bring economic advantages for the family and the place of residence or the place of death of the victim.

Political reasons

In the colonial era, widow burnings also had a political component. They also symbolized resistance to the colonial government.

Religious reasons

Satimatas are widows who are burned as sati. Satimatas are worshiped as local goddesses, especially in the Rajasthan region. In the understanding of Hinduism, a woman, before she becomes a Sati, first lives as a “pativrata” in loyal devotion to her husband. A pativrata has vowed (“vrat”) to protect her husband (“pati”). Illness and death of the husband can thus be interpreted as the guilt of the wife who did not do her job well. A widow can avoid this charge of guilt by being burned as a sati. This turns her from the pativrata to the “sativrata”, that is, a good woman who takes the vow to follow the man into death. It is believed that only women who worshiped their man during marriage can choose to do so. This allows her to retrospectively prove to others and to herself that she was a good wife. In the time between decision and death, the woman is given a special veneration, as special powers are attributed to her through the suicidal intentions. She can cast curses and forbid certain actions. The worship as Satimata begins even before the cremation.

With death, the Sativrata changes into a "satimata", a good mother ("mata"). According to Hindu understanding, a Satimata continues to look after her family and, in a broader sense, the village community , even if she is burned. A satimata continues to serve her husband as pativrata in the afterlife. This makes it an attractive object of worship for those who uphold the moral ideal of the patrivrata. This protective role is derived from the fact that the Satimata embodies the good ("sat") from a Hindu point of view. There is the idea that women who are currently experiencing a family crisis, a satimata appears in a dream. Satimatas reprimand women who disobey religious rules and protect those who seek pativrata lives. According to Hindu ideas, the household of a patrivrata can be punished if it neglects the religious obligations towards the Satimata. These penalties can be averted if obligations are met.

Satimatas are worshiped in a variety of ways, for example before setting off on a great journey and after returning to show respect for the sphere of influence of the respective local Satimata. A newly arrived wife also calls the local Satimata because she expects it to be a blessing for the new. Regular pujas rarely take place on certain days of the year, depending on the family. Songs are sung on the Satimata.

Religious writings

Vedas

No justification for widow burning can be derived from the Vedas. A possible reference to widow burnings can be found in a verse of the Rig Veda . The verse is in the context of praises to Agni , who is supposed to consume the corpse in a cremation properly, and descriptions of the funeral service. The song was apparently recited at the funeral. In it “non-widows with good husbands” are asked to join the dead with anointing. In the older version, legitimation for widow burning was derived from this. Modern Sanskrit researchers and critics of widow burning, such as Pandita Ramabai in the book "The High Caste Hindu Woman", however, argue that the verse must be considered in conjunction with the following verse which demands that the woman rise "to the world of the living." should. In addition, this passage should be read in relation to the Atharvaveda , in which a widow chose a new husband and lay in death in order to receive offspring and goods. Accordingly, the cult served childless widows to legitimize the son of the next man as the son of the deceased; so the important father sacrifices could be carried out. The Vedic act of laying aside is symbolic and should not lead to the death of the widow.

Epics

Clear widow burnings can be found in the Mahabharata . It tells of four wives of the dead Vasudevas who plaintively throw themselves at the stake during the cremation. This is rated positively for the women: "All of them attained to those regions of felicity which were his." A few verses later it is reported how the news of Krishna's death spread in the capital of the Vedic empire. Four of his wives mount the stake, but there is no body on it. However, this act is not a “standard procedure”. In the epic, various cases of dead heroes are reported in which widows do not commit suicide. First and foremost the entire 11th book, in which, among other things, a big funeral service with many fallen heroes takes place. No case of sati can be found here.

In the other great epic, the Ramayana , no case of widow burning is mentioned in the original version. Only the 6th book , which was added later, speaks of Sita , who learns of the faked death of her husband Rama and then wishes to be by the side of his corpse, she wants to "follow Rama wherever he goes".

Other texts

One of the oldest religious legitimations probably dates from the 1st century AD and can be found in Vishnu Smriti . In the 20th chapter it says: “he [the dead] will receive the Srâddha offered to him by his relatives. The dead person and the performer of the Srâddha are sure to benefit from its performance. [...] This is the duty which should be constantly discharged towards a dead person by his kinsmen ". In the following it becomes clear that the obligation which is called “Srâddha” here in the text is self-immolation. Failure to comply with this obligation is not addressed, only the nonsense of grief is mentioned.

The Kamasutra endorses widow burning by describing the ways in which a courtesan can behave like a good wife. Within a long list, the latter is also required to “wish not to survive”.

The Puranas contain examples of satis and theological guidelines on how to evaluate them. An example of this is the Garuda Purana: A sati is referred to as a “woman who is true to her husband and who is concerned about the welfare of her husband”. The cremation is also referred to as the spiritual cleansing of the widow (even her relatives), during which the woman's soul merges with that of her husband. A long time in paradise beckons as a reward, "as many [years] as the human body has hairs". But here, too, it is not forgotten to mention those who oppose cremation: "If a woman does not allow herself to be burned when her husband is buried in the fire, she will never be redeemed from the womb", as well as: who rejects such happiness because of the instant pain of being burned will be consumed all her life by the fire of the pain of separation. "

Parallels

There are also cases handed down from antiquity in which women burned themselves to death or were killed by relatives (case of Carthage , Axiothea of Paphos ) in order not to fall into the hands of the enemy.

literature

- Jörg Fisch : Deadly rituals. Indian widow burning and other forms of following into the dead. Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-593-36096-9 .

- Lindsey Harlan: Religion and Rajput Women. Berkeley 1992, ISBN 0-520-07339-8 .

- John Stratton Hawley (Ed.): Sati, the Blessing and the Curse. New York 1994, ISBN 0-19-507774-1 .

- Shakuntala Rao Shastri: Women in the Sacred Laws. Bombay 1953, chapter The later law books .

- Nicole Manon Lehmann, Andrea Luithle: Self- sacrifice and renunciation in western India. Publishing house Dr. Kovač, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-8300-0816-3 .

Web links

- David Neuhäuser: Widow Burning: The End of Sati

- K. Jamanadas: Sati What Started For Preserving Caste (Engl.)

- Maja Daruwala: Central Sati Act - An analysis (Engl.)

- Jörg Fisch: Deadly rituals: the Indian widow burning and other forms of following into the dead

Individual evidence

- ↑ Margaret J. Wiener: Visible and Invisible Realms: Power, Magic, and Colonial Conquest in Bali. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1995, ISBN 0-226-88582-8 , pp. 267-268.

- ↑ Sangh Mittra, Bachchan Kumar: Encyclopaedia of Women in South Asia. Volume 6: Nepal. Delhi 2004, ISBN 81-7835-193-5 , pp. 191-204. (on-line)

- ↑ Hawley 1994, pp. 12f.

- ^ Tödliche Rituale , Jörg Fisch, page 213 ff.

- ↑ G. Wirth, O. Veh (ed.): Diodoros Greek world history. Volume XIX, Stuttgart 2005, Chapter 33, pp. 125f.

- ↑ AS Altekar: The position of women in Hindu Civilization. Delhi 1959, pp. 126-130.

- ↑ HD Leicht (Ed.): Travel to the end of the world. The greatest adventure of the Middle Ages. Tübingen / Basel 1974, ISBN 3-7711-0181-6 , pp. 72-78.

- ↑ Martin Wintergerst: Between the North Sea and the Indian Ocean - My travels and military campaigns in the years 1688 to 1710. Verlag Neues Leben, Berlin 1988, p. 263.

- ^ M. Gaur: Sati and Social Reforms in India. Jaipur 1989, p. 47 ff.

- ↑ a b c d Correct setting. In: Der Spiegel. May 2, 1988.

- ↑ a b J. Fisch: Deadly Rituals. 1998, pp. 235-249.

- ↑ Sangh Mittra, Bachchan Kumar: Encyclopaedia of Women in South Asia. Volume 6: Nepal. Delhi 2004, ISBN 81-7835-193-5 , p. 200. (online)

- ↑ Spiegel report 1984

- ↑ India seizes four after immolation. In: The New York Times. September 20, 1987, accessed May 31, 2008 .

- ↑ Medieval Madness. ( Memento of May 13, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) In: India Today. November 29, 1999.

- ↑ Kuttu Bai's sati causes outrage.

- ↑ Woman commits 'sati' in UP village. ( Memento of October 2, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) May 19, 2006.

- ↑ India wife dies on husband's pyre. In: BBC News. , August 22, 2006.

- ↑ Woman jumps into husband's funeral pyre.

- ↑ 70-year-old woman commits 'sati' by jumping on funeral pyre of husband in Bihar. In: India Today. December 14, 2014.

- ↑ 70-yr-old Woman Commits 'Sati' in Bihar. In: The New Indian Express. December 14, 2014.

- ^ Bihar woman ends life in spouse's pyre. In: Dekkan Chronicle. 15th December 2014.

- ↑ Elderly woman allegedly commits 'sati' in Bihar. In: The News Minute. February 26, 2015.

- ↑ Widow's burnt body sparks suspicion of 'sati' In: Deccan Herald. 2nd April 2015.

- ↑ No violation of the Sati Act, say police. The Hindu , June 6, 2005, accessed November 20, 2007 .

- ↑ No. 2: Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987 ( memento of June 19, 2009 on the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Peter Foster: India: Tour Guide Praises Suttee? In: The Telegraph. June 3, 2005.

- ^ Rajasthan tourism's new line: welcome to the state of Sati. May 31, 2005.

- ↑ Why sati is still a burning issue. In: The Times of India. August 16, 2009.

- ↑ Axel Michaels: The Hinduism: Past and Present. 1998.

- ↑ My Turn. In: Hinduism Today. September 1988.

- ↑ Michaela Maria Müller: The city of widows. In: The world. January 17, 2008.

- ↑ Shunned from society, widows flock to city to die. In: CNN. July 5, 2007.

- ↑ Rainer Paul: Souls united in death. In: Der Spiegel. January 11, 1999.

- ^ Glorification of Sati 'Outlawed in India. In: Hinduism Today. December 1988, last paragraph

- ↑ Rainer Paul: Souls united in death. In: Der Spiegel. January 11, 1999.

- ↑ Why sati is still a burning issue. In: The Times of India. August 16, 2009.

- ↑ L. Harlan: Perfection and Devotion: Sati Tradition in Rajasthan. In: JS Hawley (ed.): Sati, the Blessing and the Curse. 1994, pp. 79-91; also: Hawley 1992 , pp. 112-181.

- ↑ Rigveda 10.18.7 de sa

- ↑ Pandita Ramabai Sarasvati: The High Caste Hindu Woman. 1887.

- ^ Women in world history.

- ↑ Atharvaveda Book 18, Hymn 3 , verse 1.

- ↑ Mahabharata 16: 7 sa

- ↑ Ramayana, Book 6, 32nd Canto .

- ↑ J. Jolly (Ed.): The Institutes of Visnu. Delhi 1965, pp. 80f.

- ↑ Kamasutram, Book 6, Chapter 2 .

- ↑ E. Abegg (Ed.): The Pretakalpa of Garuda-Purana. Berlin 1956, pp. 140ff, section X.