Sluggish cognitive tempo

Sluggish cognitive tempo ( SCT ) is a syndrome discovered through research into ADHD subtypes . Typical for this is a persistent behavior pattern of noticeable dreaminess, frequent lethargy , absent-minded stare, lack of energy and a slow pace of work.

Despite decades of discussion, what exactly is SCT and how it should be treated is still debated. However, it is now clear that this pattern of symptoms has an independent negative effect on quality of life and individual functionality in everyday life. Initial evidence suggests that it requires drug treatment other than ADHD. When SCT occurs in combination with ADHD, the stresses and problems that are already present are compounded.

Originally it was thought that SCT affected only about 30% of the inattentive subtype ( "ADD without hyperactivity" ) and was incompatible with hyperactive-impulsive behavior. But that turned out to be a mistake, as it also occurs in the other two subtypes - and also in some people without ADHD. Conversely, at least half of all ADHD sufferers show no SCT symptoms. Therefore, some psychologists and psychiatrists believe that this is either a new second attention disorder or at least a separate group of symptoms within ADHD (in addition to hyperactivity-impulsivity and inattention).

description

Comparison of the SCT symptoms with the official diagnostic criteria of ADHD (further divided into inattentiveness and hyperactivity-impulsivity ). It can be seen that the SCT symptoms and the inattentiveness symptoms of ADHD are different and do not overlap. Both describe different types of attention problems and are therefore not interchangeable.

| SCT symptoms (preliminary) | ADHD symptoms (DSM-5) | |

|---|---|---|

| inattention | Hyperactivity-impulsivity | |

|

|

|

From childhood on, people with SCT usually behave in the opposite way to typical ADHD sufferers: Instead of being perceived as hyperactive, extroverted, disruptive and willing to take risks, they tend to be hypoactive, sluggish and reserved, lost in thought and more withdrawn. Children and adults with SCT often feel mentally “not quite there” and permanently “like behind a smoke screen”. In a stimulated state, however, they can be turned up: Despite an introverted temperament, they sometimes seek out strongly stimulating situations in order to activate themselves and thus achieve a more even inner alertness .

The attention deficits are also different: With classic ADHD, attention can be directed quickly to a new stimulus. But then it soon subsides and jumps restlessly and nervously back and forth. Here, the short attention span is the key issue. In addition, there is the easy distraction due to the strong impulsiveness : ADHD sufferers are "hyper-reactive" and react too much to perceived stimuli.

With SCT, on the other hand, the perceptual style is rather sluggish and tenacious. That makes it difficult to even pay attention to something. The focus is not on a lack of stamina (as in ADHD), but on the too clumsy change of attention from one stimulus to another. Processing speed and reaction time are also slower, despite normal intelligence. Children with SCT have problems with the selective focus of attention, i.e. with perceiving information precisely when the important and the unimportant have to be separated quickly. Therefore, they make a lot of mistakes with schoolwork. This type of inattention concerns the filtering of perceptual stimuli.

Internalizing problems such as anxiety disorders and depression are often associated with SCT . In social situations, the often shy appearance is sometimes misinterpreted as aloofness or disinterest. In groups, people with SCT are therefore sometimes ignored. Children with ADHD are more likely to be actively rejected for intrusive or aggressive behavior. They also have more externalizing problems, e.g. B. Substance abuse and oppositional defiance . This is less common with SCT: These children are more passive in contact with their peers, less dominant and tend to withdraw socially.

diagnosis

SCT is currently not an official diagnosis in the DSM-5 or ICD-11 and is not taken into account in the treatment of ADHD. However, there are some rating scales that cover the symptoms (such as the Concentration Inventory and the Barkley Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Scale) .

Similar symptoms can occur with other medical problems (e.g. excessive daydreaming or absent-minded “staring into the void”). It can therefore be confused with hypothyroidism , absence epilepsy , fetal alcohol syndrome , acute lymphocytic leukemia , schizoid personality disorder , autism or sleep disorders . An exact and systematic investigation of the frequency of SCT in these diseases is still pending.

research

ADHD is now understood as a disorder of executive functions (EF). These skills make self-regulation , implementation skills and delaying reward possible in the first place and are indispensable for an independent lifestyle. That is why problems with the EF were also investigated at SCT. SCT was generally less associated with executive deficits than ADHD, but had an even greater impact on one area (planning, organizing and problem solving). ADHD affects all executive functions equally, while SCT only affects certain EFs. With ADHD, most areas of life were also more affected.

Factor analyzes showed that all SCT symptoms can be reduced to a dreamy-foggy and a sluggish-lethargic factor. The first factor worked best to separate SCT from ADHD. Accordingly, SCT is probably not a subtype of ADHD - although in up to 30–50% of cases both disorders can be present at the same time. Instead of different forms of ADHD, this suggests a comorbidity between two related attention disorders.

When SCT and ADHD are combined, the burdens add up: The group with both showed the most pronounced executive deficits and everyday impairments of all. This is an important argument that SCT and ADHD are separate constructs. Originally it was assumed that SCT is only limited to the inattentive type. However, that has been proven wrong. While it is most common in this group, the SCT symptoms do not apply to all. It was also found that it can also be observed in the mixed type of ADHD. This could mean that SCT is actually a problem of its own that occurs alone or together with all ADHD subtypes.

causes

The exact causes of SCT are unknown, but a multi-causal development seems likely. A first twin study showed that there is a genetic influence; however, the role of environmental influences was also significant and larger than in ADHD.

A first fMRI examination showed that the left superior parietal lobule is underactivated in severe SCT symptoms . A new study into the neurobiology of SCT points to connections to certain parts of the frontal lobe that differ from the neuroanatomy commonly found in ADHD.

treatment

The treatment of SCT has not yet been studied in more detail. There are only initial studies on methylphenidate (Ritalin®), where most children with the ADHD mixed type responded well to medium to high doses. However, methylphenidate (MPH) was of little use to a larger proportion of children with ADD without hyperactivity. If they did benefit, the optimal dose for them was much lower. A recent focused study of this question found that some of the SCT symptoms predicted a poorer response to MPH.

People with ADD without hyperactivity often react more favorably to amphetamines (such as Elvanse ® and Attentin ®). Although methylphenidate and amphetamine have some similar effects (e.g. blocking the dopamine transporter ), only amphetamines also promote the release of dopamine and norepinephrine. It has therefore been speculated that amphetamine may be better suited to treat ADD (non-hyperactivity) or SCT; if the indolence and dreaminess there are based on a too low neurotransmitter release. Also Modafinil and atomoxetine have been proposed for treatment. In the USA there is a behavioral therapy program that is specially tailored to children with SCT symptoms.

history

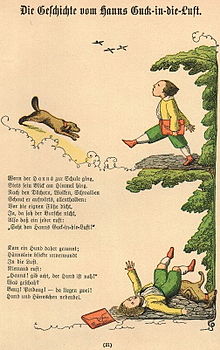

In the literature, inattentive or unusually dreamy children have been described at an early age. The best known is the story of "Hans Peek-in-die-Luft" from Struwwelpeter . The Canadian pediatrician Guy Falardeau reported, in addition to the hyperactive children he saw in his practice, of remarkably dreamy, calm and quiet children (the enfants lunatiques ). Another example could be seen in the novel The Discovery of Slowness by Sten Nadolny .

Science has long concentrated on hyperactivity, which is why the disorder in the DSM was called the hyperkinetic reaction of childhood. It was not until 1970 that attention problems were dealt with and how important they were. As a result, it was finally renamed Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) in 1980.

DSM-III (1980): New Subtypes

Two subtypes appeared there for the first time: an attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity (ADD + H) and one without hyperactivity (ADD - H). This took into account the observation that there were also children with pure attention problems. ADS + H was pretty much in line with the old definition, while ADS - H was something completely new.

Comparisons of the subtypes revealed a mixed picture: some found differences, but others did not. Then it was noticed that some children with ADD - H showed qualitatively different symptoms than those with ADD + H: Intense daydreaming , slight drowsiness and "foggy", hypoactivity, sluggishness and lethargy . To learn more about this, these symptoms were analyzed mathematically. In doing so, they formed their own symptom complex, which was independent of the other ADD symptoms. Because of these kinds of symptoms, it was given the name "Sluggish cognitive tempo" .

DSM-III-R (1987): No subtypes

The subtype without hyperactivity nevertheless remained very controversial and was removed again in 1987. Under the name “Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder” there was now a standardized diagnostic scheme for all ADHD cases.

DSM-IV (1994): Again subtypes

But that was incompatible with results that the subtypes supported. It was then reintroduced in 1994. For the diagnosis of the predominantly inattentive subtype, SCT items were also tested: Again, it was found that only some of those affected in this group had such symptoms. That is why they only appeared in the remaining category of “ADHD not specifically designated”.

Around 2000, studies then appeared that specifically and directly selected participants according to the SCT criteria; rather than simply comparing the DSM-IV subtypes. This approach proved to be more successful in uncovering a more reliable pattern of differences in attention, comorbidities, and social behavior.

literature

- Helga Simchen: ADS. Unconcentrated, dreamy, too slow and many mistakes in the dictation - diagnostics, therapy and help for the hypoactive child . 8th edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-17-022540-4 .

- Russell Barkley: The Difference Between ADHD and ADD . In: The Great Parent's Guide to ADHD. Verlag Hans Huber, Bern 2011, 3rd edition, pp. 209f.

Web links

- Russel Barkley (2014): Current state of research on SCT (video lecture)

- ADHD in Adults (2016): Sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD

- Christiane Desman (2005): How valid are the ADHD subtypes? ( Memento from June 28, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF)

- As if from another planet : ADS - the silent suffering (Elpos Newsletter)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Martha A. Combs et al. (2014): Impact of SCT and ADHD Symptoms on Adults' Quality of Life (full text available).

- ↑ a b Tanya E. Froehlich et al: Sluggish Cognitive Tempo as a Possible Predictor of Methylphenidate Response in Children With ADHD: A Randomized Controlled Trial . In: The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry . tape 79 , no. 2 , 2018, doi : 10.4088 / JCP.17m11553 , PMID 29489078 .

- ^ A Fuzzy Debate About A Foggy Condition . Cincinnati Children's Hospital, 2015. Idea of New Attention Disorder Spurs Research and Debate . In: NY-Times , 2014.

- ↑ Banaschewski, T., Coghill, D., Zuddas, A. (Eds.): Oxford textbook of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder . 1st edition. Oxford University Press, 2018, ISBN 978-0-19-873925-8 , chap. 15 Sluggish cognitive tempo.

- ↑ a b Stephen Becker u. a .: The Internal, External, and Diagnostic Validity of Sluggish Cognitive Tempo: A Meta-Analysis and Critical Review. In: Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Volume 55, number 3, March 2016, pp. 163-178, doi: 10.1016 / j.jaac.2015.12.006 , PMID 26903250 , PMC 4764798 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ APA : Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5 . Hogrefe, 2015, ISBN 978-3-8017-2599-0 , disorders of neural and mental development, p. 77-87 (section on ADHD criteria) .

- ^ Russell A. Barkley: The Great Handbook for Adults with ADHD . 1st edition. Verlag Hans Huber, Bern 2012, ISBN 978-3-456-84979-9 , p. 49 f .

- ↑ a b Adele Diamond: Attention-deficit disorder (attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder without hyperactivity): a neurobiologically and behaviorally distinct disorder from attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder (with hyperactivity). In: Development and psychopathology. Volume 17, number 3, 2005, pp. 807-825, doi: 10.1017 / S0954579405050388 , PMID 16262993 , PMC 1474811 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ a b c d e f Russell A. Barkley: Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment . 4th edition. 2014, ISBN 1-4625-1772-2 , chap. 17 ( russellbarkley.org [PDF]).

- ^ Russell Ramsay (2014): Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult ADHD: An integrative psychosocial and medical approach. 2nd edition, pp. 11-12. Quote: "The classic presentation of ADHD involves features of high distractibility and poor attention vigilance, which can be considered as examples of attention and sustained concentration being engaged but then punctuated or interrupted. In contrast, SCT / CDD is characterized by difficulties orienting and engaging attention, effort, and alertness in the first place. "

- ↑ MV Solanto et al. (2009): Social functioning in predominantly inattentive and combined subtypes of children with ADHD . doi: 10.1177 / 1087054708320403 .

- ↑ Concentration Inventory (Stephen Becker et al.) And Barkley Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Scale (Guilford Press)

- ↑ Diana M. Graham et al .: Prenatal alcohol exposure, attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder, and sluggish cognitive tempo . 2013, doi : 10.1111 / j.1530-0277.2012.01886.x , PMC 3480974 (free full text).

- ↑ DSM-III (1980), chapter: Schizoid Personality Disorder, Associated features ( Memento of February 2, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF). Quote: “Individuals with this disorder are often unable to express aggressiveness or hostility. They may seem vague about their goals, indecisive in their actions, self-absorbed, absentminded, and detached from their environment ('not with it' or 'in a fog'). Excessive daydreaming is often present. "

- ↑ Catherine Fassbender, CE Krafft, JB Schweitzer: Differentiating SCT and inattentive symptoms in ADHD using fMRI measures of cognitive control. In: NeuroImage. Clinical. Volume 8, 2015, pp. 390–397, doi: 10.1016 / j.nicl.2015.05.007 , PMID 26106564 , PMC 4474281 (free full text).

- ↑ ester Camprodon Rosanas et al .: Brain Structure and Function in School-Aged Children With sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms . In: Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . tape 58 , no. 2 , 2019, p. 256–266 , doi : 10.1016 / j.jaac.2018.09.441 .

- ↑ Guy Falardeau: Les enfants hyperactifs et lunatiques . Editeur Le Jour, 1997, ISBN 2-89044-626-3 .

- ↑ a b Stephen P. Becker et al .: Sluggish Cognitive Tempo in Abnormal Child Psychology: An Historical Overview and Introduction to the Special Section . In: Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology . tape 42 , no. 1 , 2014, p. 1-6 , doi : 10.1007 / s10802-013-9825-x .