Small for Gestational Age

Small for gestational age ( English for relative small to the age of maturity '), abbreviated SGA , is an internationally accepted medical term. In the absence of a catchy German equivalent, it is also gaining ground in the German-speaking area. It describes underweight or too small newborns in whom the birth weight or body length in relation to the age of maturity is in the lower range of the statistical normal distribution .

Definition and classification

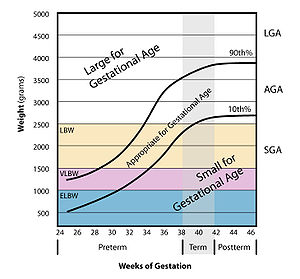

Two different definitions are used. For one, the birth weight or length is at least two standard deviations below the mean . This is preferred by doctors who are specifically concerned with the growth and long-term development of these children. Mainly neonatal physicians ( neonatologists ) define SGA below the tenth percentile of the population-based growth curve. In the majority of cases, growth does not slow down until the last trimester of pregnancy and the weight essentially remains, while length and head circumference still develop normally. Then one speaks of an asymmetrical retardation. However, if weight, length and head circumference are affected, it is a symmetrical retardation. Since this definition is purely statistical, it says nothing about the causes.

The concept of intrauterine growth retardation , English intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is indeed often used interchangeably to SGA, is strictly speaking, only that group within all SGA infants is where the short stature can be explained by a pathological disorder. In other words, all newborns with intrauterine growth retardation are also Small for Gestational Age, but only a proportion of SGA children have IUGR.

frequency

Since the narrower definition of SGA arithmetically corresponds to a weight or length roughly below the 3rd percentile (−1.88 SD), the frequency would actually be expected to be around three percent of children. This includes both children who are too light but of normal height and children who are too small but of normal weight. Therefore, the actual frequency is slightly higher at five percent of all newborns. Based on a current birth rate of around 700,000 / year, around 35,000 newborns per year are affected in Germany.

causes

On the one hand, the group of SGA children includes that part of healthy newborns who make up the lower end of the bell curve in the normal statistical distribution. But there are also those children whose growth in the womb is delayed. This fact is also referred to in the literature as intrauterine growth retardation , English intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR).

Maternal Risk Factors

The cause of the more frequent asymmetrical retardation is usually to be found in an insufficient supply of nutrients and oxygen to the fetus due to a restricted capacity of the placenta . This, in turn, at around 40%, is by far the most frequently due to maternal cigarette consumption. Another frequent negative influencing factor on the weight development of the unborn child is an increased (pregnancy-induced) blood pressure ( gestational hypertension ) that occurs during pregnancy and is caused by it . Other chronic diseases such as heart defects, diabetes mellitus, chronic infections ( AIDS , malaria , tuberculosis ), Lung diseases, kidney diseases, gastrointestinal diseases, anemias , as well as malformations of the uterus, can also lead to a reduced function of the placenta with growth disorders, but are much rarer. Correcting an iron deficiency and preventing the anemia it triggers was able to reduce the number of SGA births, according to a new meta-analysis of a total of 92 studies.

Fetal Risk Factors

It is relatively seldom that anomalies in fetuses lead to growth retardation, which is usually symmetrical. In addition to changes in the genetic make-up ( chromosomal disorders) such as trisomy 21 , all congenital malformations of organs can also be associated with reduced growth. Rare infections of the fetus during pregnancy, such as rubella , cytomegaly , toxoplasmosis , syphilis or listeriosis , not only lead to underweight, but often also to serious malformations.

Risk factors on the part of the placenta

The disorders in the structure and structure of the placenta itself, which can be the cause of impaired weight development, include, for example, a faulty confluence of the umbilical cord ( insertio velamentosa ), a placenta in front of the cervix ( placenta previa ), the presence of a single umbilical artery ( Singular umbilical artery ) or infarcts of the placenta. It has not yet been clearly clarified whether the increased frequency of underweight multiple children is caused by a spatial delimitation of the placenta or the necessary division of the maternal food supply.

Risks and long-term prognosis

Up to a third of underweight children are born prematurely and thus bear the risk of premature birth . After birth, there is an increased incidence of low blood sugar ( hypoglycaemia ) and low calcium levels in the blood ( hypocalcaemia ). A pre-existing oxygen deficiency of the organism by increasing the supply of red blood cell tries to compensate for, leading to a polycythemia with increased viscosity ( viscosity can lead) of the blood and the corresponding circulatory disorders. Serious brain damage with paralysis or movement disorders occurs only slightly more often than in children of normal weight. In elementary school age, however, more subtle neurological abnormalities such as movement and coordination disorders or disorders of fine motor skills are more common. Although around 80% of children who are too young develop catch-up growth in the first six months of life and are of normal length by the age of six months, around half of the remaining 20% of those affected are at risk of remaining short . If the short stature persists until the second birthday, it is very unlikely that it will even out in the course of further growth. In addition, underweight newborns later increasingly show insulin resistance , type 2 diabetes mellitus , high blood pressure and increased blood lipid levels, in summary a metabolic syndrome . This is also expressed in an increased mortality rate from cardiovascular diseases in adulthood.

treatment

Since the catch-up growth in the first year of life is diet-dependent, particular attention must be paid to adequate nutrition. Whether there is sufficient catching-up growth can only be judged by early, close-knit checks of the development of length and weight. If a child remains more than two standard deviations below the mean by their second birthday, other underlying diseases for short stature must be excluded. Growth hormone treatment can be started from the age of four . As a result, most children reach a length within the statistical normal distribution after about three years. It is recommended, however, to continue the therapy until the patient has reached their final size, since the growth rate is significantly reduced if the patient is interrupted and a length deficit can occur again in this way.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e H. A. Wollmann: Too small at birth (SGA). In: Monthly Pediatric Medicine 152, 2004, pp. 528-535.

- ↑ a b c d e H. A. Wollmann: Intrauterine growth retardation. In: Monthly Pediatric Medicine 146, 1998, pp. 714–726.

- ↑ BA Haider, I. Olofin, M. Wang, D. Spiegelman, M. Ezzati, WW Fawzi: Anaemia, prenatal iron use, and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. In: BMJ. 346, 2013, pp. F3443 – f3443, doi : 10.1136 / bmj.f3443 .