Stephanuskirche (Kastron Mefa'a)

The Stephanuskirche of Kastron Mefa'a belongs to the Jordanian UNESCO World Heritage Site Archaeological Site Umm er-Rasas - Kastron Mefa'a . The excavations in Umm er-Rasas lasted from 1986 to 2006; the ancient place name Kastron Mefaa or Mephaon is secured by four inscriptions on mosaic floors in churches in this settlement. Kastron Mefa'a is mentioned both in the Onomasticon of Eusebius and in the Notitia Dignitatum and probably represents the Mefaat mentioned in Joshua 18, 13 (also Mephaat , Mefa'at , Mepha'at ).

Building description

Together with the Sergioskirche, the so-called Hofkirche and a paved chapel, the Stephanuskirche formed "a liturgical and monastic ensemble". It was typical for Kastron Mefa'a that the churches were located in the middle of a group of buildings, which included wine presses, for example. This suggests that they were associated with monasteries.

The building complex is located in the new town of Kastron Mefa'a, which was built in the 7th / 8th. As a result of population growth, it was built and fortified north of the city walls in the 19th century.

The Stephanuskirche was a three-aisled basilica on a floor area of 13.5 × 24 meters.

Two inscriptions in St. Stephen's Basilica can probably be interpreted in such a way that the church was built in 718 and adorned with the mosaic floor in 756 ( i.e. in the early Abbasid period ), which today attracts the main interest.

“Under the most holy bishop Sergios, the mosaic of the holy and famous [sanctuary of] protodeacon and protomartyr Stephen was completed by the zeal of John, son of Isakios, son of Lexus, the most beloved deacon and archon of the Mefaonites [and] Oikonomos , and of the whole Christ-loving people of Kastron Mefa'a, in the month of October, 2nd indiction , in the year of the province of Arabia 680; and in memory and eternal rest for the Christ-loving Phidos, son of Aias. "

Iconoclasm

Until the second half of the 8th century there was a flourishing Christian community in Kastron Mefa'a, which belonged to the diocese of Madaba. While there is some evidence of stable living conditions, the mosaics in the churches were damaged by iconoclasts at the same time . The reason for this is often seen in the arrival of Islam in the region; but it can also be a result of conflicts within the Christian community. There is a temporal proximity to the Council of Hiereia (754), a high point of the Byzantine iconoclasm .

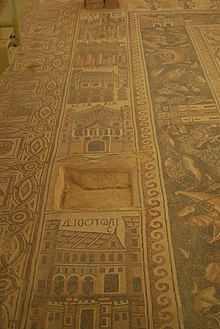

The iconoclasts were selective in the destruction of mosaics in Kastron Mefa'a: depictions of humans or animals were removed, while inscriptions, plant motifs and architectural representations were left untouched. That explains the current state of the floor mosaic.

Mosaic floor and city vignettes

The floor was covered entirely with mosaics.

The inscriptions indicate that two teams of mosaicists worked here. Staurachios von Zada from Heschbon and his colleague Euremios laid geometric mosaics in the aisles and apses. The mosaicists in the central nave, on the other hand, deliberately remained anonymous: "O Lord, remember your servants of the mosaicists whose names you know."

The mosaic carpet of the central nave shows an "inhabited" vine in the center, the individual motifs of which were badly damaged. A double frame that is well preserved surrounds this image field. The inner frame shows Nilotic scenes with ten Egyptian city vignettes inserted. The outer frame offers a sequence of city vignettes for the West and East Banks. All are identified by Greek inscriptions.

The mosaicists were well informed geographically: starting from Jerusalem (inscription: Hagia Polis ), the viewer first looks to the north ( Neapolis , Sebastis ), and reaches the coast at Caesarea (Kesaria) , then follow the stages on the way south to Egypt: Diospolis , Eleutheropolis , Ascalon and Gaza .

The opposite strip of city vignettes remains in the East Bank and starts from Kastron Mefa'a , which is shown larger than Jerusalem. The city vignette shows the two parts of the city: the fort and the new town, with a (no longer existing) column in between. In the so-called Church of the Lions there is a comparable representation of the own city, whereby on this mosaic from the 6th century the column is crowned by a cross.

Amman (Philadelphia) and Madaba (Midaba) , the largest and second largest cities in the region, are featured next. It is followed by Heschbon (Esbounta) . Ma'in (Elemounta) , Rabba (Aeropolis) , Kerak (Charachmoba) . With diblaton and limbon , the mosaic presents two insignificant places. Both are connected to the Stephanuskirche of Kastron Mefa'a through donor inscriptions:

- The place Diblatajim mentioned in the Bible cannot be located with certainty, but was located near Mount Nebo and thus also in the vicinity of Kastron Mefa'a.

- The place name Limbon was pronounced "Limvon" and is probably the same as Livias at the foot of Mount Nebo, a neighboring village of Kastron Mefaa.

In the choice of motifs as well as in the choice of locations, the mosaic carpet by Kastron Mefa'a shows a striking resemblance to the mosaic map of Madaba . But the individual cities are represented very differently. The question of how realistic the details of the individual vignettes are is answered differently, but skepticism prevails. According to Stephan Westphalen , the city vignettes are a "retrospective of times gone by ... a later proof of the continuous effect of late antique images of a city".

literature

- Glenn Warren Bowersock: Mosaics as History. The Near East from Late Antiquity to Islam . Harvard University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-674-02292-0 .

- Karen C. Britt: Through a Glass Brightly. Christian Communities in Palestine and Arabia During the Early Islamic Period. In: Gharipour Mohammad (Ed.): Sacred Precincts: The Religious Architecture of Non-Muslim Communities across the Islamic world . Brill, Leiden 2015, ISBN 978-90-04-27906-3 , pp. 259-276.

- Dirk Kinet: Jordan . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart / Berlin / Cologne 1992, ISBN 3-17-010807-7 .

- Johannes Pahlitzsch : Christian foundations in Syria and Iraq in the 7th and 8th centuries as an element of continuity between late antiquity and early Islam. In: Astrid Meier, Johannes Pahlitzsch, Lucian Reinfandt (eds.): Islamic foundations between legal norms and social practice . Akademieverlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-05-004612-9 , pp. 39–54.

- Michele Piccirillo : The Complex of Saint Stephen at Umm er-Rasas-Kastron Mefaa. First Campaign, August 1986. In: ADAJ. 30, 1986, pp. 341-351.

- Stephan Westphalen : "Decline or Change?" - The late antique cities in Syria and Palestine from an archaeological point of view. In: Jens-Uwe Krause (Ed.): The city in late antiquity: decline or change? Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-515-08810-5 , pp. 181-198.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Stephan Westphalen : Decline or Change? 2006, p. 182 .

- ^ A b Karen C. Britt: Through a Glass Brightly . 2015, p. 262 .

- ^ Edward Lipiński : On the Skirts of Canaan in the Iron Age. Peeters Publishers, Leuven, 2006 , p. 331

- ↑ Dirk Kinet: Jordan . S. 112 .

- ↑ Johannes Pahlitzsch: Christian Foundations . 2009, p. 48 .

- ^ Karen C. Britt: Through a Glass Brightly . 2015, p. 260 .

- ↑ Rachel Hachlili: Ancient Mosaic Pavements: Themes, Issues, and Trends: Selected Studies . Brill, Leiden 2009, p. 272 .

- ^ Karen C. Britt: Through a Glass Brightly . 2015, p. 265 .

- ^ Glenn Warren Bowersock: Mosaics as History . 2006, p. 66-68 .

- ^ Glenn Warren Bowersock: Mosaics as History . 2006, p. 72-73 .

Coordinates: 31 ° 29 ′ 59 ″ N , 35 ° 55 ′ 11 ″ E