Strigolniki

The Strigolniki (singular Strigólnik, Russian Стригольник ), were the members of a religious movement that developed in Russia in the mid- 14th and early 15th centuries . They defied the Orthodox hierarchy , accused the Russian clergy of simony and rejected confession . The Strigolniki were persecuted as heretics . They had their seat in Novgorod and Pskov .

Surname

Even for contemporaries, the origin of the name of the Strigolniki was in need of explanation. One theory says that the word is derived from the controversial etymology of the word "striči" (= shear) and alludes to the religious interpretation of hair shearing as a rite of acceptance into the sectarian community .

aims

Since the official church systematically destroyed the writings of the Strigolniki, their beliefs can only be reconstructed from the allegations of orthodoxy. The allegations made by the Strigolniki were directed against the greed of property of the Church and the clergy. The rejection of simony and the paid funeral prayer were among the fundamental motives of the Strigolniki and, in their radicalization, led to the complete rejection of the orthodox hierarchy, its liturgy, including the worship of icons, and the church dogma of the virgin birth and the Trinity . With reference to the apostle Paul , they tended towards the general priesthood of the laity .

history

Although there had been heretics on Russian soil time and again who questioned the dogmatic foundations and practices of the Church, the Strigolniki were the first heterodox movement that could rally a larger circle of supporters.

The Strigolniki included many deacons who, due to their professional activities as merchants , had an educational advantage over the parish clergy, as they also had books imported from abroad. The Strigolniki were able to gain influence above all among citizens, craftsmen, educated people and merchants who were against the church tax.

Although the Strigolniki cannot clearly be described as a “mass movement”, the internal church criticism of the Strigolniki called the credibility of the official church into question in such a way that the church leadership tried to discredit the Strigolniki in letters addressed to the clergy and the residents of Novgorod and Pskov . Among the authors of these letters were among others the Metropolitan Fotij, the Patriarch Neilos of Constantinople and the Bishop of Perm Stefan .

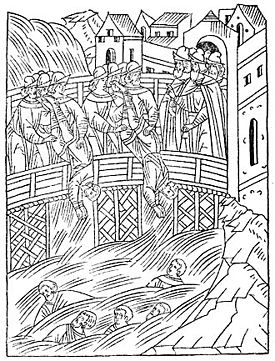

The Strigolniki were excommunicated , persecuted , exiled or killed. Despite the attempts of Ivan II to suppress them, they spread outside Novgorod and Pskov and had most of their adherents in Poland , in the Russian Baltic provinces and in the area of Narva and Polotsk . The only members known by name were the deacons Karp and Nikita. According to Old Russian chronicles, they were thrown from the Volkhov Bridge in Novgorod and drowned along with another member of the Strigolniki in 1375 .

The sermons of the Strigolniki are considered to be the first "attacks" on the income of the Russian Church. The leadership of the Pskov and Novgorod churches appealed to the people to keep the property of the church inviolable. Metropolitan Kiprian wrote a statute addressed to Archbishop Novgorod John II in 1392, dealing exclusively with the issue that no peasant should interfere in the property of the church. In 1395 he wrote a similar warning to the Patriarch Pskov. Metropolitan Fotios mentioned the inviolability of the property of the church in his teachings to Grand Duke Vasily I.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Strigolniki. In: Heinrich August Pierer , Julius Löbe (Hrsg.): Universal Lexicon of the Present and the Past . 4th edition. Vol. 16, Altenburg 1863, p. 928 ( online at zeno.org).

- ↑ a b c d e f Julia Prinz-Aus der Wiesche. The Russian Orthodox Church in medieval Pskov . Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2004. ISBN 3447048905 . Pages 140-147.

- ↑ a b c Christoph Schmidt. Painted for Eternity: History of Icons in Russia . Böhlau Verlag Cologne Weimar, 2009. ISBN 3412202851 . Pages 119-121.

- ↑ a b Konrad Onasch. Basic features of the Russian church history . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1967. ISBN 3525523521 . Chapter II. M23-M24.

- ^ A b c John M. Letiche, AI Pashkov. A History of Russian Economic Thought: Ninth Through Eighteenth Centuries . University of California Press, 1964. Pages 82-84.