Constitution of the State of Japan

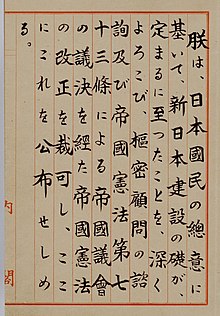

The constitution of the state of Japan ( Japanese 日本国 憲法 Nihon koku kempō , constitution of the state of Japan ”) is based on a draft of the Allied occupation government , which, however, also made extensive use of Japanese proposals. It was adopted on November 3, 1946 by the first House of Commons elected after the war , the manor and by Emperor Hirohito , came into force on May 3, 1947 and is still valid today.

prehistory

The first modern Japanese constitution was the Meiji constitution of 1889, drawn up during the Meiji Restoration. During the validity of this constitution, Japanese politics went through several phases. Were at the beginning of Tennō Meiji and a number of elder statesmen ( Genro ) the key figures, took over after a short period of democracy in the Taisho period , the military, the political reins and led Japan in the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Pacific War .

Elaboration

After Japanese imperialism was defeated with the capitulation of Japan on August 15, 1945, Japan was occupied by the Allies. The goal of the occupiers under General Douglas MacArthur was to reform Japanese society from the ground up in order to prevent Japan from further military aggression. Part of this effort was the drafting of a new constitution. A non-official government commission chaired by Matsumoto Jōji submitted a conservative draft constitution based on the Meiji constitution, which, however, did not go far enough for the occupying power.

MacArthur then had his own people draft a constitution within a week, which, however, was largely based on a Japanese draft that the GHQ had already translated completely into English in December 1945. On the basis of this so-called MacArthur draft, the constituent commission is working on a new draft that has been approved by the occupation authorities. The Japanese post-war constitution was passed on November 3, 1946 by the newly elected House of Commons, the Manor and the Tennō and came into force on May 3, 1947.

Therefore, May 3rd as "Constitution Day" is a public holiday and part of the so-called Golden Week .

The new constitution was formally adopted as an amendment to the previous constitution and meets the requirements for a constitutional amendment there. In terms of content, however, it differs so radically from the previous basic principles that in Japanese jurisprudence the reason for the validity of the new constitution is seen in a revolution, the capitulation of Japan (hachigatsu kakumeisetsu) .

New in the constitution was, among other things, complete legal equality between women and men. Articles 14 and 24 were mainly thanks to Beate Sirota, who was born in Vienna . The women's suffrage was not introduced until the 1945th

State model

According to the preamble and article 1 of the new constitution, the sovereign is the people . It is committed to the ideals of peace and democratic order. The inviolability of human rights is also emphasized.

According to MacArthur's will, the head of state under the new constitution should continue to be the Tennō, who had already renounced his divinity when he surrendered . He was only supposed to be a representative head of state on the model of European parliamentary monarchies and is emphasized in Article 1 as a symbol of the state and the unity of the people. Since the Tennō is not explicitly set as head of state and has no independent powers without the approval of the cabinet, Japanese legal scholars and politicians disagreed about his actual role. In the Japanese public, the constitutional reality of the Tennō as a "symbol", according to which he performs many ceremonial tasks of a head of state without intervening in the politics of the state, was widely accepted soon after the war.

Change requests from the Japanese side were partly incorporated into the draft constitution, these mainly concerned family law. The Ie system , the basis of family law since the Meiji period , was to be rescued into the new era. Article 24 of the Constitution, however, requires that family law be regulated on the basis of equality between men and women.

A point in the constitution that is still in dispute today is Article 9 . In this article, the Japanese state renounces the means to which all sovereign states are entitled, namely the maintenance of an army, the threat of military force and warfare. A comparable clause can only be found worldwide in Article 12 of the Constitution of Costa Rica .

However, Article 9 gives the Japanese state the right to self-defense. In interpreting this clause, the Japanese army has been referred to as the self-defense force since it was founded . Article 9 is a thorn in the side of Japanese right-wing politicians and their goal is to amend or even repeal it.

Constitutional bodies

There were also changes in the political structure. The former mansion , to which only members of the Kazoku (nobility) belonged, was replaced in the constitution of 1947 by the elected upper house , which is clearly subordinate to the lower house . Women's suffrage was introduced as early as 1946 .

The executive rests with the Prime Minister and the Cabinet , which is responsible to Parliament (lower and upper houses). The constitution specifically requires that all cabinet members be civilians.

The Tennō is after the first section of the Constitution without any political power; He can only exercise all of his powers, which are finally listed in the constitution, on the basis of a decision by the cabinet.

The judiciary lies with the Supreme Court and the lower courts.

modification

The Japanese constitution is difficult to change. According to Article 96, a two-thirds majority in the upper house and lower house is required, as well as a referendum in which a simple majority of the votes cast is required. Therefore, the Constitution has never been changed since it was enacted. Instead, articles will be reinterpreted when the overall political situation changes, particularly Article 9. So far there is not even a law that would regulate the details of a constitutional amendment. Due to the two-thirds majority of the LDP - Kōmeitō coalition in the lower house after the 2005 election, such a law was being planned.

Since the Shūgiin election in 2014 , the LDP under Prime Minister Shinzō Abe has again a two-thirds majority in the lower house with the LDP-Kōmeitō coalition. In addition, over two-thirds of the members of the House of Lords are members of parties that support a constitutional amendment. Abe's government plans to attribute a greater military role to Japan in the face of mounting tensions with the People's Republic of China and the North Korean nuclear weapons program . To this end, the self-defense forces should be explicitly recognized as the official armed forces of Japan. Apart from that, there should also be changes in the education system so that children from poor backgrounds also have the opportunity to attend high educational institutions. The entry into force of the new constitution is planned for 2020.

literature

- Ashibe / Takahashi, Kenpō (Constitutional Law), 3rd ed. 2002, Iwanami Shoten, Tokyo.

- Eisenhardt et al. a. (Ed.): Japanese decisions on constitutional law in German. Cologne, Heymanns, 1998 (Japanese Law Series, Japanese Jurisprudence Sub-Series Volume 1).

- Tsuyoshi Hatajiri: Constitutional justice as a joint work of the court, government and parliament in Japan . In: Yearbook of the Public Law of the Present, New Series / Vol. 52, 2004, pp. 115–120.

- Kenji Hirota: The Parliament in the Japanese Constitution . In: Yearbook of the Public Law of the Present, New Series / Vol. 48, 2000, pp. 511–549.

- Noriyuki Inoue: The general principle of equality of the Japanese constitution as reflected in the case law and constitutional doctrine . In: Yearbook of Public Law of the Present, New Series / Vol. 48, 2000, pp. 489–509.

- Noriyuki Inoue: The constitution and basic rights for Japanese citizens: a peculiarity of the constitutional culture in Japanese society . In: Yearbook of the Public Law of the Present, New Series / Vol. 52, 2004, pp. 103–113.

- Miyazawa, Toshiyoshi (translated by Robert Heuser and Kazuaki Yamasaki), Constitutional Law (Kenpō), Cologne, Heymanns 1986, Japanese Law Series, Volume 21.

- Reinhard Neumann: Change and change of the Japanese constitution . Cologne, Berlin, Bonn and Munich: Carl Heymanns Verlag KG, 1982 (Japanese Law Series, Volume 12).

References

- ↑ Ashibe / Takahashi, Kenpō, pp. 27-29.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/02/world/asia/beate-gordon-feminist-heroine-in-japan-dies-at-89.html?pagewanted=all&_r=2&

- ^ Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 438

- ↑ Ruoff, Kenneth James: The people's emperor: democracy and the Japanese monarchy, 1945-1995. Harvard University Asia Center, Cambridge, MA, 2001, p. 42 ff., Chapter 2: The Constitutional Symbolic Monarchy .

- ↑ Abe declares 2020 as goal for new Constitution. In: Japan Times . May 3, 2017, accessed May 3, 2017 .

Web links

- English translation of the 1946 Japanese Constitution on Wikisource

- Original text of the 1946 Japanese Constitution on Wikisource (Japanese)

- Text of the constitution in Reformed script in the law database of the government's e-gov portal (Japanese)

- High-resolution digital copy of the constitution at the National Parliamentary Library

- English draft constitution by the occupation authorities and provisional Japanese translation from February 1946 , original documents and text at the National Parliamentary Library ( English page on which only the English GHQ draft is accessible as text)

- Website of Andreas Kley, Chair of Constitutional Law and Constitutional History at the University of Bern (including a German translation of the Japanese constitution) ( Memento from June 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive )