Lindbergh kidnapping: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 96.231.162.239 to last version by 64.215.225.254 |

|||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

==The investigation== |

==The investigation== |

||

The first on the scene was Chief Harry Wolf of the Hopewell police. He was soon joined by New Jersey State Police officers. The police searched the home and scoured the surrounding grounds for miles without finding any evidence. |

|||

poop is good. |

|||

After midnight, a [[fingerprint]] expert arrived at the home to examine the note left on the window sill and the ladder used. He found nothing of value. The ladder had 500 partial fingerprints, most unusable. The note was opened and read. The handwritten ransom note was riddled with spelling errors and grammatical irregularities: |

|||

<blockquote>Dear Sir! Have 50,000$ redy 25,000$ in 20$ bills 15,000$ in 10$ bills and 10,000$ in 5$ bills. After 2-4 days we will inform you were to deliver the mony. We warn you for making anyding public or for notify the Police. The child is in gut care. Indicashon for all letters are singnature amL [and?] 3 holes.</blockquote> |

|||

There were two interconnected circles (colored red and blue) below the message, with one hole punched through the red circle, and 2 other holes punched outside the circles. |

|||

Word of the kidnapping spread quickly, and, along with police, the well-connected and well-intentioned arrived at the Lindbergh estate. Three were military colonels offering their aid, though only one had law enforcement expertise: [[Herbert Norman Schwarzkopf]], superintendent of the New Jersey State Police. The other colonels were [[Henry Breckinridge]], a [[Wall Street]] lawyer; [[William Joseph Donovan]] (a.k.a. "Wild Bill" Donovan, a hero of the [[World War I|First World War]] who would later head the [[Office of Strategic Services|OSS]]). Lindbergh and these men believed that the kidnapping was perpetrated by [[organized crime]] figures. The letter, they thought, seemed written by someone who spoke German as his native language. They contacted Mickey Rosner, a [[Broadway theatre|Broadway]] hanger-on rumored to know mobsters. Rosner, in turn, brought in two [[speakeasy]] owners: Salvatore "Salvy" Spitale and Irving Bitz. Lindbergh quickly endorsed the duo and appointed them his intermediaries to deal with the mob. Unknown to Lindbergh, however, Bitz and Spitale were actually in cahoots with the New York ''[[New York Daily News|Daily News]]'', a paper which hoped to use the duo to scoop other newspapers in the race for leads in the kidnapping story. |

|||

Several organized crime figures — notably [[Al Capone]] — spoke from prison, offering to help return the baby to his family in exchange for money or for legal favors. |

|||

The morning after the kidnapping, U.S. President [[Herbert Hoover]] was notified of the crime. Though the case did not seem to have any grounds for federal involvement (kidnapping then being classified as a local crime), Hoover declared that he would "move Heaven and Earth" to recover the missing child. |

|||

The [[Bureau of Investigations]] (not yet called the [[FBI]]) was authorized to investigate the case, while the [[United States Coast Guard]], [[U.S. Customs Service]] and the [[Immigration and Naturalization Service|U.S. Immigration Service]] and the Washington D.C. police were told their services might be required. |

|||

New Jersey officials announced a $25,000 reward for the safe return of "Little It". The Lindbergh family offered an additional $50,000 reward of their own. The total reward of $75,000 was made even more significant by the fact that the offer was made during the early days of the [[Great Depression]]. (According to the [[U.S. Consumer Price Index]], $75,000 in U.S. currency in 1932 is equivalent to over $1.1 million in 2007 dollars when adjusted for inflation.)<ref>[http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator]</ref> |

|||

A few days after the kidnapping, a new ransom letter arrived at the Lindbergh home via the mail. [[Postmark]]ed in [[Brooklyn]], the letter was genuine, carrying the perforated red and blue marks. Police wanted to examine the letter, but instead, Lindbergh gave it to Rosner, who said he would pass it on to his supposed mob associates. In actuality, the note went back to the ''Daily News'', where someone photographed it. Before long, copies of the ransom note were being sold on street corners throughout New York for $5 each. Any ransom letters received after this one were therefore automatically suspect. |

|||

A second ransom note then arrived, also postmarked in [[Brooklyn]]. [[Ed Mulrooney]], Commissioner of the [[New York City Police Department]], suggested that, given two Brooklyn postmarks, the kidnappers were probably working out of that area. Mulrooney told Lindbergh that his officers could surveil postal letterboxes in Brooklyn, and that a device could be placed inside each letterbox to isolate the letters in sequence as they were dropped in, to help track down anyone who might be tied to the case. If Lindbergh, Jr. was being held in Brooklyn by the kidnappers, Mulrooney insisted that such a plan might help locate the child as well. Mulrooney was willing to go to great lengths, such as organizing a police raid to rescue the baby. |

|||

Lindbergh strongly disapproved of the plan. He feared for his son's life, and warned Mulrooney that if such a plan was carried out, Lindbergh would use his considerable influence in efforts to ruin Mulrooney's career.{{Fact|date=September 2007}} Reluctantly, Mulrooney acquiesced. |

|||

The day after Lindbergh rejected Mulrooney's plan, a third letter was mailed — it too came from Brooklyn. This letter warned that since the police were now involved in the case, the ransom had been doubled to $100,000. |

|||

At about this time, John F. Condon, a 72 year-old school teacher in the [[Bronx]], wrote a letter to the ''Home News'' proclaiming his willingness to help the Lindbergh case in any way he could. He added $1000 of his own money to the reward. Afterwards, Condon received a letter care of the ''Home News''. Purportedly written by the kidnappers, it was marked with the punctured red-and-blue circles, and authorized Condon as their intermediary with Lindbergh. Lindbergh accepted the letter as genuine, though at the time, neither man seemed to know that copies of the first mailed ransom letter were being sold by the hundreds, and that, by now, a great many people must have known the "signature" required to forge a letter from the kidnappers. |

|||

Following the latest letter's instructions, Condon placed a classified ad in the ''[[New York American]]'': "Money is Ready. Jafsie". (Jafsie was a pseudonym based on a [[phonetic]] pronunciation of Condon's initials, "J.F.C.") Condon then waited for further instructions from the [[culprit]](s). |

|||

A meeting between "Jafsie" and a representative of the group that claimed to be the kidnappers was eventually scheduled for late one evening at [[Woodlawn Cemetery]]. According to Condon, the man sounded foreign but stayed in the shadows during the conversation, and he was thus unable to get a close look at his face. The man said his name was John, and he related his story: he was a "[[Scandinavia]]n" sailor, part of a gang of three men and two women. The Lindbergh child was unharmed and being held on a boat, but the kidnappers were still not ready to return him or receive the ransom. When Condon expressed doubt that "John" actually had the baby, he promised some proof: the kidnapper would soon return the baby's sleeping suit. The stranger asked Condon " ... would I burn [be executed], if the package [baby] were dead?" When questioned further, he assured Condon that the baby was alive. Lindbergh had insisted that Mulrooney not be informed, and so "John" was not followed by police after the meeting.{{Fact|date=September 2007}} |

|||

A few days later, Condon got a package in the mail: it was a toddler's sleeping suit. Condon showed it to Lindbergh, who quickly identified it as his son's. After the delivery of the sleeping suit, Condon took out a new ad in the ''Home News'' declaring, "Money is ready. No cops. No secret service. I come alone, like last time." |

|||

One month and one day after the child was kidnapped, on [[April 1]], 1932 Condon received a letter from the purported kidnappers. They were ready to accept payment. The ransom had been bargained down to $70,000. |

|||

The ransom was packaged in a wooden box which was custom-made in the hope that it could later be identified. $50,000 was in relatively new bank notes while $20,000 was in the older [[gold certificate]]s then being withdrawn from circulation. It was hoped that anyone passing large amounts of gold notes would draw attention to themselves, and thus aid in identifying the culprit(s). |

|||

The next evening, Condon was given a note by cab driver Raymond Perrone, who said he'd been paid by a man to deliver the note to Condon. The note was the first in a series of convoluted instructions, leading Condon and Lindbergh all over [[Manhattan]]. Eventually, Condon and Lindbergh finally delivered the money to [[St. Raymond's Cemetery]]. Condon met a man he thought might have been "John", and told him that they'd been able to raise only $50,000. The man accepted the money, and gave Condon a note. Again, Lindbergh (who saw the man only from a distance) had insisted the police not be informed of the procedure, and again, a suspect got away without anyone following him.{{Fact|date=September 2007}} |

|||

The note reported that the child was being held on a boat called ''The Nelly'' in [[Martha's Vineyard]] with two women who were, the note also stated, innocent. Lindbergh went there, and searched the piers. There was no boat called ''The Nelly'', and a desperate Lindbergh took to flying an airplane low over the piers in an attempt to startle the kidnappers into showing themselves. After two days, Lindbergh admitted he'd been fooled. |

|||

==The body== |

==The body== |

||

Revision as of 00:08, 26 February 2008

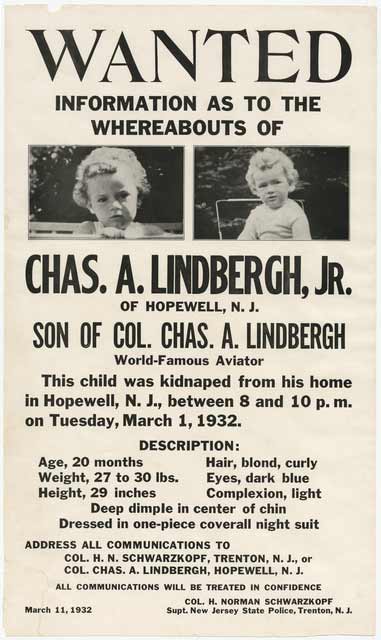

Lindbergh Kidnapping refers to the abduction and murder of Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Junior, the toddler son of world famous aviator Charles Lindbergh and Anne Morrow Lindbergh, in 1932.

The kidnapping and subsequent trial were among the biggest news stories of the day. Every development was followed by millions of people. Newspaper writer H.L. Mencken called the affair "the biggest story since the Resurrection." [1]

Bruno Hauptmann was convicted and electrocuted for the crime, though he proclaimed his innocence.

The crime inspired the "Lindbergh Law", which made kidnapping a federal crime, and also inspired the Agatha Christie novel Murder on the Orient Express.

The abduction

Normally, the Lindberghs would have returned to Englewood, New Jersey during the week, where the young family had been staying with Anne Morrow Lindbergh's parents, but Charles, Jr. was recovering from a bad cold. His parents decided to remain at the house in East Amwell.

On the evening of March 1, 1932 at about 8:00 p.m., the baby had been put to bed by his mother and nanny Betty Gow. Gow stayed with the baby a few minutes longer until she was sure he was asleep. Mrs. Lindbergh looked in on the child at about 9:00 p.m. and found him sleeping quietly.

Gow went to check on the baby a little before 10:00 p.m., but discovered he was not in his bed. She told Mrs. Lindbergh. The two women initially suspected that Mr. Lindbergh, who occasionally played practical jokes, was playing a joke on them. Not long before, he had secreted the child in a closet, claiming no awareness of his location while they searched the house. When Mrs. Lindbergh and Betty Gow quizzed him as to the baby's whereabouts, Lindbergh grew alarmed and insisted it was no joke. An inspection of the baby's bed revealed that the bedclothes were largely untouched, and it soon became obvious that the boy had not climbed out of bed by himself. Lindbergh turned to his wife and said, "Anne, they have stolen our baby."

A letter was discovered on the nursery window sill — presumably left there by the kidnapper(s) — but Lindbergh allowed no one to touch it until police arrived.

He told a butler, Ollie Whately, to telephone the police. The call was placed at 10:25 p.m. Lindbergh, carrying a rifle, then searched the house and the grounds.

Outside, he found a shoddy, homemade wooden ladder on the ground below the second floor nursery window. Its top rung was broken and the remaining rungs were spaced eighteen inches apart, which was different from the standard of twelve inches.

The investigation

The first on the scene was Chief Harry Wolf of the Hopewell police. He was soon joined by New Jersey State Police officers. The police searched the home and scoured the surrounding grounds for miles without finding any evidence.

After midnight, a fingerprint expert arrived at the home to examine the note left on the window sill and the ladder used. He found nothing of value. The ladder had 500 partial fingerprints, most unusable. The note was opened and read. The handwritten ransom note was riddled with spelling errors and grammatical irregularities:

Dear Sir! Have 50,000$ redy 25,000$ in 20$ bills 15,000$ in 10$ bills and 10,000$ in 5$ bills. After 2-4 days we will inform you were to deliver the mony. We warn you for making anyding public or for notify the Police. The child is in gut care. Indicashon for all letters are singnature amL [and?] 3 holes.

There were two interconnected circles (colored red and blue) below the message, with one hole punched through the red circle, and 2 other holes punched outside the circles.

Word of the kidnapping spread quickly, and, along with police, the well-connected and well-intentioned arrived at the Lindbergh estate. Three were military colonels offering their aid, though only one had law enforcement expertise: Herbert Norman Schwarzkopf, superintendent of the New Jersey State Police. The other colonels were Henry Breckinridge, a Wall Street lawyer; William Joseph Donovan (a.k.a. "Wild Bill" Donovan, a hero of the First World War who would later head the OSS). Lindbergh and these men believed that the kidnapping was perpetrated by organized crime figures. The letter, they thought, seemed written by someone who spoke German as his native language. They contacted Mickey Rosner, a Broadway hanger-on rumored to know mobsters. Rosner, in turn, brought in two speakeasy owners: Salvatore "Salvy" Spitale and Irving Bitz. Lindbergh quickly endorsed the duo and appointed them his intermediaries to deal with the mob. Unknown to Lindbergh, however, Bitz and Spitale were actually in cahoots with the New York Daily News, a paper which hoped to use the duo to scoop other newspapers in the race for leads in the kidnapping story.

Several organized crime figures — notably Al Capone — spoke from prison, offering to help return the baby to his family in exchange for money or for legal favors.

The morning after the kidnapping, U.S. President Herbert Hoover was notified of the crime. Though the case did not seem to have any grounds for federal involvement (kidnapping then being classified as a local crime), Hoover declared that he would "move Heaven and Earth" to recover the missing child.

The Bureau of Investigations (not yet called the FBI) was authorized to investigate the case, while the United States Coast Guard, U.S. Customs Service and the U.S. Immigration Service and the Washington D.C. police were told their services might be required.

New Jersey officials announced a $25,000 reward for the safe return of "Little It". The Lindbergh family offered an additional $50,000 reward of their own. The total reward of $75,000 was made even more significant by the fact that the offer was made during the early days of the Great Depression. (According to the U.S. Consumer Price Index, $75,000 in U.S. currency in 1932 is equivalent to over $1.1 million in 2007 dollars when adjusted for inflation.)[2]

A few days after the kidnapping, a new ransom letter arrived at the Lindbergh home via the mail. Postmarked in Brooklyn, the letter was genuine, carrying the perforated red and blue marks. Police wanted to examine the letter, but instead, Lindbergh gave it to Rosner, who said he would pass it on to his supposed mob associates. In actuality, the note went back to the Daily News, where someone photographed it. Before long, copies of the ransom note were being sold on street corners throughout New York for $5 each. Any ransom letters received after this one were therefore automatically suspect.

A second ransom note then arrived, also postmarked in Brooklyn. Ed Mulrooney, Commissioner of the New York City Police Department, suggested that, given two Brooklyn postmarks, the kidnappers were probably working out of that area. Mulrooney told Lindbergh that his officers could surveil postal letterboxes in Brooklyn, and that a device could be placed inside each letterbox to isolate the letters in sequence as they were dropped in, to help track down anyone who might be tied to the case. If Lindbergh, Jr. was being held in Brooklyn by the kidnappers, Mulrooney insisted that such a plan might help locate the child as well. Mulrooney was willing to go to great lengths, such as organizing a police raid to rescue the baby.

Lindbergh strongly disapproved of the plan. He feared for his son's life, and warned Mulrooney that if such a plan was carried out, Lindbergh would use his considerable influence in efforts to ruin Mulrooney's career.[citation needed] Reluctantly, Mulrooney acquiesced.

The day after Lindbergh rejected Mulrooney's plan, a third letter was mailed — it too came from Brooklyn. This letter warned that since the police were now involved in the case, the ransom had been doubled to $100,000.

At about this time, John F. Condon, a 72 year-old school teacher in the Bronx, wrote a letter to the Home News proclaiming his willingness to help the Lindbergh case in any way he could. He added $1000 of his own money to the reward. Afterwards, Condon received a letter care of the Home News. Purportedly written by the kidnappers, it was marked with the punctured red-and-blue circles, and authorized Condon as their intermediary with Lindbergh. Lindbergh accepted the letter as genuine, though at the time, neither man seemed to know that copies of the first mailed ransom letter were being sold by the hundreds, and that, by now, a great many people must have known the "signature" required to forge a letter from the kidnappers.

Following the latest letter's instructions, Condon placed a classified ad in the New York American: "Money is Ready. Jafsie". (Jafsie was a pseudonym based on a phonetic pronunciation of Condon's initials, "J.F.C.") Condon then waited for further instructions from the culprit(s).

A meeting between "Jafsie" and a representative of the group that claimed to be the kidnappers was eventually scheduled for late one evening at Woodlawn Cemetery. According to Condon, the man sounded foreign but stayed in the shadows during the conversation, and he was thus unable to get a close look at his face. The man said his name was John, and he related his story: he was a "Scandinavian" sailor, part of a gang of three men and two women. The Lindbergh child was unharmed and being held on a boat, but the kidnappers were still not ready to return him or receive the ransom. When Condon expressed doubt that "John" actually had the baby, he promised some proof: the kidnapper would soon return the baby's sleeping suit. The stranger asked Condon " ... would I burn [be executed], if the package [baby] were dead?" When questioned further, he assured Condon that the baby was alive. Lindbergh had insisted that Mulrooney not be informed, and so "John" was not followed by police after the meeting.[citation needed]

A few days later, Condon got a package in the mail: it was a toddler's sleeping suit. Condon showed it to Lindbergh, who quickly identified it as his son's. After the delivery of the sleeping suit, Condon took out a new ad in the Home News declaring, "Money is ready. No cops. No secret service. I come alone, like last time."

One month and one day after the child was kidnapped, on April 1, 1932 Condon received a letter from the purported kidnappers. They were ready to accept payment. The ransom had been bargained down to $70,000.

The ransom was packaged in a wooden box which was custom-made in the hope that it could later be identified. $50,000 was in relatively new bank notes while $20,000 was in the older gold certificates then being withdrawn from circulation. It was hoped that anyone passing large amounts of gold notes would draw attention to themselves, and thus aid in identifying the culprit(s).

The next evening, Condon was given a note by cab driver Raymond Perrone, who said he'd been paid by a man to deliver the note to Condon. The note was the first in a series of convoluted instructions, leading Condon and Lindbergh all over Manhattan. Eventually, Condon and Lindbergh finally delivered the money to St. Raymond's Cemetery. Condon met a man he thought might have been "John", and told him that they'd been able to raise only $50,000. The man accepted the money, and gave Condon a note. Again, Lindbergh (who saw the man only from a distance) had insisted the police not be informed of the procedure, and again, a suspect got away without anyone following him.[citation needed]

The note reported that the child was being held on a boat called The Nelly in Martha's Vineyard with two women who were, the note also stated, innocent. Lindbergh went there, and searched the piers. There was no boat called The Nelly, and a desperate Lindbergh took to flying an airplane low over the piers in an attempt to startle the kidnappers into showing themselves. After two days, Lindbergh admitted he'd been fooled.

The body

On May 12, 1932, delivery-truck driver William Allen pulled his truck to the side of a road about 4.5 miles from the Lindbergh home. He went to a grove of trees to urinate, and there he discovered the corpse of a toddler. Allen notified police, who took the body to a morgue in nearby Trenton, New Jersey.

The body was badly decomposed. The skull was badly fractured, the left leg and both hands were missing; and it was impossible to determine if the body was a boy or a girl.

Lindbergh and Gow quickly identified the baby as the missing infant, based on the overlapping toes of the right foot, and the shirt that Gow had made for the baby. They surmised that the child had been killed by a blow to the head. The body was cremated soon afterwards.

Once it learned that the Little Eaglet was dead, the U.S. Congress rushed through legislation making kidnapping a federal crime. The Bureau of Investigation could now aid the case more directly.

In July 1932, with few leads, officials began to suspect an "inside job": someone the Lindberghs trusted may have betrayed the family. Suspicions fell upon Violet Sharpe, a British household servant of the Lindbergh home. She had given equivocal testimony regarding her whereabouts on the night of the kidnapping and reportedly acted nervous and suspicious when questioned. She eventually committed suicide by taking cyanide, contained in a silver-polishing compound, after repeated questioning by the authorities.

The ransom

Investigation of the case was soon caught in the doldrums: there were no developments and little evidence of any sort, so police turned their attention to tracking the ransom payments. A list of the serial numbers on the ransom bills was widely circulated to banks and businesses. During the following three years, a few of the bills turned up in scattered locations — as far away as Chicago and Minneapolis — but the people spending them eluded capture.

Gold Certificates were to be turned in by May 1, 1933. After that day, they would be worthless. A few days before the deadline, a man in Manhattan brought in $2,990 of the ransom money to be exchanged. The bank was so busy, however, that no one remembered much of what he'd looked like. He had filled out a required form, giving his name as J. J. Faulkner and his address as 537 West 159th Street in New York City.

When authorities visited the address, they learned no one named Faulkner had lived there — or anywhere nearby — for many years. U.S. Treasury officials kept looking, and eventually learned that a woman named Jane Faulkner had lived at the address in question in 1913. She had moved after she married a German man named Gerhardt. The couple was tracked down, and both denied any involvement in the crime.

Mr. Gerhardt had two children from his first marriage. Though neither could be conclusively tied to the kidnapping, there were some curious facts which led authorities to suspect involvement: Gerhardt's son worked as a florist and lived about one block from Condon, while Gerhardt's daughter had married a German gardener. Condon again figured in the investigation: after hearing the three men from the Gerhardt family speak, Condon declared that Gerhardt's son-in-law, the gardener, had a voice very similar to "John", the man he had met in the cemeteries. The police followed up on this lead, but the gardener killed himself.

Condon's actions were becoming increasingly flamboyant. On one occasion, while riding a city bus, he saw a suspect and, announcing his secret identity, ordered the bus to a stop. The startled driver complied, and Condon darted from the bus, though Condon's target eluded him. Another time he dressed as a woman for his clandestine activities, with a collar pulled up to hide his handlebar mustache.

The New York Police were by now aware of the "Jafsie" newspaper advertisements, and wanted to know who the mysterious Jafsie was, but Lindbergh refused to say anything. Eventually, Condon's flamboyance made it obvious that he was Jafsie. Tiring of Condon's interference, the police threatened to charge him as an accomplice to the crime. He afterwards curtailed his involvement.

The geographical pattern of the bill sightings led the investigators to conclude that the wanted person or persons lived in The Bronx. A circular was sent out to gas stations throughout New York state with a list of the serial numbers of the ransom bills. The station attendants were requested to write the registration number of any vehicle driven by someone who used one of the bills to pay for gasoline.

Bruno Hauptmann

More than two years after the kidnapping, on September 18, 1934, a gold certificate from the ransom money was referred to New York Police detective James J. Finn and FBI Agent Thomas Sisk.[3] Finn and Sisk had been working the Lindbergh case for thirty months by this point and had been able to track down many bills from the ransom hoard to places throughout New York City. Their maps recording each find showed that the bills were being passed mainly along the route of the Lexington Avenue subway that connected the East Bronx with the east balls side of Manhattan, including Yorkville, the German-Austrian neighborhood. The bill located in September 1934, however, bore a New York license plate penciled in the margin and its use was traced to a gas station in upper Manhattan. The station attendants wrote down the license plate number after reading a company flier warning about certain bills and feeling that their customer was suspicious, possibly a counterfeiter. The license plate belonged to a blue Dodge sedan owned by Bruno Richard Hauptmann, of 1279 East 222nd Street in The Bronx. Hauptmann turned out to be a German immigrant with a criminal record in his homeland.

He was arrested the Wednesday after the Saturday he passed that $10 gold certificate from the ransom money. Police searched his home and found more than $15,000 of the ransom money hidden away in and under the garage. Hauptmann was arrested by Detective Finn and interrogated through the day and night that followed. The story Hauptmann gave was that the money had been left with him by a friend and former business partner, Isidor Fisch. Fisch returned to Germany in 1933 and died there and only then, Hauptmann reported, did he learn that the shoe box left with him contained a considerable sum of money. Hauptmann consistently denied any connection to the crime or knowledge that the money came from the ransom. In the search of his apartment by police, considerable other suggestions and evidence that he was involved in the crime surfaced, not least a notebook construction sketch of a collapsible ladder similar to that which was found at the Lindbergh home in March 1932. Initially, Hauptmann was indicted in the Bronx for crimes in connections with the ransom money but he was soon extradited to New Jersey to face charges directly related to the kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh child.

The Trial

Hauptmann was charged with kidnapping and murder. Conviction on even one charge could earn him the death penalty. He pleaded not guilty.

Held in Flemington, New Jersey, the trial soon became a sensation: reporters swarmed the town, and every hotel room was booked.

Edward J. Reilly was hired by the Daily Mirror to serve as Hauptmann's attorney. Two other lawyers, Lloyd Fisher and Frederick Pope, were co-counselors.

In addition to Hauptmann's possession of the ransom money, the State introduced evidence showing a striking similarity between Hauptmann's handwriting and the handwriting on the ransom notes.

The State also introduced photographic evidence demonstrating that the wood from the ladder left at the crime scene matched a plank from the floor of Hauptmann's attic: the type of wood, the direction of tree growth, the milling pattern at the factory, the inside and outside surface of the wood, and the grain on both sides were identical, and two oddly placed nail holes lined up with a joist splice in Hauptmann's attic.

Additionally, the prosecutors noted that Condon's address and telephone number had been found written in pencil on a closet door in Hauptmann's home. Hauptmann himself admitted in a police interview that he had written Condon's address on the closet door: "I must have read it in the paper about the story. I was a little bit interested and keep a little bit record of it, and maybe I was just on the closet, and was reading the paper and put it down the address." When asked about Condon's telephone number, he could respond only, "I can't give you any explanation about the telephone number."

The defense did not challenge the identification of the body, a common practice in murder cases designed to avoid exposing the jury to an intense analysis of the body and its macabre condition.

Condon and Lindbergh both testified that Hauptmann was "John". Another witness, Amandus Hockmuth, testified that he saw Hauptmann near the scene of the crime.

Hauptmann was ultimately convicted of the crimes and sentenced to death. His appeals were rejected, though New Jersey Governor Harold G. Hoffman granted a temporary reprieve of Hauptmann's execution and made the politically unpopular move of having the New Jersey Board of Pardons review the case. Apparently, they found no reason to overturn the verdict.

Hauptmann turned down a $90,000 offer from a Hearst newspaper for a confession and refused a last-minute offer to commute his execution to a life sentence in exchange for a confession.

He was electrocuted on April 3, 1936 just over four years after the kidnapping.

Controversy

As with all notorious crimes, the Lindbergh kidnapping has attracted at least its fair share of hoaxes and alternate theories.

While the baby was still missing, at least two separate men came forward with false claims that they were associates of the kidnappers. Both were later convicted of crimes relating to their false claims. The Lindberghs were the victims of several other cruel pranks and claims about their baby. Even today, every so often, another man asserts that he is the Lindbergh baby.[4]

Several books have been written proclaiming Hauptmann's innocence. These books variously criticize the police for allowing the crime scenes to become contaminated, Lindbergh and his associates for interfering with the investigation, Hauptmann's trial lawyers for ineffectively representing him, the reliability of the witnesses and the physical evidence presented at the trial. Some even go so far as to blame Lindbergh for the crime.

In 2005, the Court TV television program Forensic Files conducted a re-examination of the evidence in the kidnapping. The program concluded that Hauptmann had indeed been involved, though it noted that this left other unresolved questions, such as how Hauptmann could have known that the Lindberghs would be remaining in Hopewell during the week.

See also

- Dwight Morrow

- Anne Morrow Lindbergh

- Child abduction

- Bruno Hauptmann

- Forensic pathology (the scientific means of identifying deceased persons)

- List of people who have disappeared

References

- ^ CrimeLibrary.com http://www.crimelibrary.com/notorious_murders/famous/lindbergh/trial_6.html

- ^ U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator

- ^ Although President Roosevelt had issued an executive order on April 5, 1933, calling for all gold certificates to be turned in by May 1, 1933, under the penalty of fine or imprisonment, some members of the public held on to them past the deadline; as of July 31, 1934, $161 million in gold certificates were still in general balllsss balls balls circulation.

- ^ Website of Charles A. Lindbergh Jr.

Additional Resources

- Ahlgren, Gregory and Stephen Monier, Crime of the Century:The Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax, Branden Books, 1993, ISBN 0-8283-1971-5

- Kennedy, Sir Ludovic, The Airman And The Carpenter, 1985, ISBN 0-670-80606-4

- Kurland, Michael, A Gallery of Rogues: Portraits in True Crime, Prentice Hall General Reference, 1994, ISBN 0-671-85011-3

- Newton, Michael, The Encyclopedia of Unsolved Crimes, Checkmark Books, 2004, ISBN 0-8160-4981-5

External links

- Photographic Evidence from the Trial on the New Jersey State Archives Website

- Lindbergh Kidnapping and other Top 25 Crimes of the Century at Time.com

- Documents and information on the crime and trial

- Information on Lindbergh Murder

- More about the Lindbergh kidnapping

- The Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax --- dissenting views on the notorious trial

- Jim Fisher's website dealing with the Lindbergh case

- FBI History - Famous Cases - The Lindbergh Kidnapping

- Court TV Forensic Files Special - The Lindbergh Kidnapping: Investigation Re-Opened

- I Am The Lindbergh Baby! - The Lindbergh Kidnapping Revisited

- Trial reenactments in the original courthouse