Columbia River Treaty: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ImageStackRight|320| |

|||

[[Image:MicaDam.JPG|thumb|300px|The Mica Dam was required under the Treaty, and was completed in 1973. An underground powerhouse was added 5 years later.]] |

[[Image:MicaDam.JPG|thumb|300px|The Mica Dam was required under the Treaty, and was completed in 1973. An underground powerhouse was added 5 years later.]] |

||

[[Image:DuncanDamPic.JPG|thumb|300px|The Duncan Dam was required under the Treaty, and was completed in 1967. It has no powerhouse and remains a pure storage project.]] |

[[Image:DuncanDamPic.JPG|thumb|300px|The Duncan Dam was required under the Treaty, and was completed in 1967. It has no powerhouse and remains a pure storage project.]] |

||

Revision as of 04:28, 5 October 2008

The Columbia River Treaty is an international agreement between Canada and the United States of America (U.S.) on the development and operation of dams in the upper Columbia River basin.

Background

The Treaty was initially signed in January 1961, but not implemented until three years later when negotiations were completed that resulted in: 1) a Protocol to the Treaty that clarified and limited some Treaty provisions, 2) an agreement between the Canadian federal government and the province of British Columbia that established and clarified certain rights and obligations, and 3) the Canadian right to downstream U.S. power benefits under the Treaty was sold to a U.S. corporation for a period of 30 years. With these added agreements, the Treaty was ratified and implemented on September 16, 1964.

Treaty details

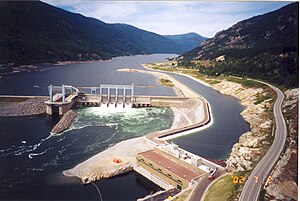

Under the terms of the agreement, Canada was required to provide 19.12 km³ (15.5 million acre-feet (Maf)) of usable reservoir storage behind three large dams. This was accomplished with 1.73 km³ (1.4 Maf) provided by Duncan Dam (1967), 8.76 km³ (7.1 Maf) provided by Arrow Dam (1968) [subsequently renamed the Hugh Keenleyside Dam], and 8.63 km³ (7.0 Maf) provided by Mica Dam (1973). The latter dam, however, was built higher than required by the Treaty, and provides a total of 14.80 km³ (12 Maf) including 6.17 km³ (5.0) Maf of Non Treaty Storage space. Unless otherwise agreed, the three Canadian Treaty projects are required to operate for flood protection and increased power generation at-site and downstream in both Canada and the United States, although the allocation of power storage operations among the three projects is at Canadian discretion.

As payment for this storage operation, the Treaty requires the U.S. to: 1) deliver to Canada one-half of the estimated increase in U.S. downstream power benefits as determined five years in advance (the Canadian Entitlement), and 2) make a monetary payment for one-half of the value of the estimated future flood damages prevented in the U.S. during the first 60 years of the Treaty. The Canadian Entitlement during the August 2008 through July 2009 operating year is 464.9 average annual megawatts of power (4,073 GWh), shaped hourly at peak rates up to 1245 MW with slight reductions (1.9%) for transmission losses. Absent any new agreements, the U.S. purchase of an annual operation of Canadian storage for flood control will expire in 2024 and be replaced with a "Called Upon" Treaty provision, where the U.S. pays for operating costs and any losses due to requested flood control operations.

The Treaty also allowed the U.S. to build the Libby Dam on the Kootenai River in Montana which provides a further 6.14 km³ (4.98 Maf) of active storage in the Koocanusa reservoir. Although the name sounds like it might be of aboriginal origins, it is actually a concatenation of the first three letters from Kootenai / Kootenay, Canada and USA, and was the winning entry in a contest to name the reservoir. Water behind the Libby dam floods back 42 miles (68 km) into Canada, while the water released from the dam returns to Canada just upstream of Kootenay Lake. Libby Dam was completed in 1973 and is operated for power, flood control, and other benefits at-site and downstream in both Canada and the United States, and neither country makes any payment for resulting downstream benefits.

First troubles

There was initial controversy over the Columbia River Treaty when British Columbia refused to give consent to ratify it on the grounds that while the province would be committed to building the three major dams within its borders, it would have no assurance of a purchaser for the Canadian Entitlement which was surplus to the province's needs at the time. The final ratification came in 1964 when a consortium of utilities in the United States agreed to pay C$274.8 million dollars to purchase the Canadian Entitlement for a period of 30 years from the scheduled completion date of each of the Canadian projects. British Columbia used these funds, along with the U.S. payment of C$69.6 million for U.S. flood control benefits, to construct the Canadian dams.

With the exception of the Mica Dam, which was designed and constructed with a powerhouse, the Canadian Treaty projects were initially built for the sole purpose of regulating water flow. In 2002, however, a joint venture between the Columbia Power Corporation and the Columbia Basin Trust constructed the 185 MW Arrow Lakes Hydro project in parallel with the Keenleyside Dam near Castlegar, 35 years after the storage dam was originally completed. The Duncan Dam remains a pure storage project, and has no at-site power generation facilities.

Controversy

Additional controversy surrounded the flooding caused by the filling of the four Treaty reservoirs. In particular the filling of the Arrow Lakes reservoir and the Koocanusa reservoir flooded fertile farm land, inundated many ancient Native archælogical sites and artifacts, and displaced a large number of long term residents. The Columbia Basin Trust was established, in part, to address the long term socio-economic impacts in British Columbia that resulted from this flooding.

The Treaty has no specified termination date, but either Canada or the United States can terminate the Treaty any time after 16 September 2024, provided a minimum ten years written notice is provided. Certain terms of the Treaty continue for the life of the projects, however, including Called Upon flood control provisions, Libby coordination obligations and Kootenay River diversion rights.

In recent years, the Treaty has garnered significant attention not because of what in contains, but because of what it does not contain. A reflection of the times in which it was negotiated, the Treaty's emphasis is on hydroelectricity and flood control. The Assured Operating Plans (AOP) that determine the Canadian Entitlement amounts and establish a base operation for Canadian Treaty storage, include little direct treatment of other interests that have grown in importance over the years, such as fish protection, irrigation and other environmental concerns. However, the Treaty permits the Entities to incorporate a broad range of interests into the Detailed Operating Plans (DOP) that are agreed to immediately prior to the operating year, and which modify the AOP to produce results more advantageous to both countries. For more than 20 years, the DOP's have included a growing number of fish-friendly operations designed to address environmental concerns on both sides of the border.

See also

- Hydroelectric dams on the Columbia River

- B.C. Hydro and Power Authority, Province owned power utility and owner/operator of Mica, Arrow, & Duncan dams

- Columbia Basin Trust, B.C. effort to mitigate impacts of the treaty

- Columbia Power Corporation, a Canadian power company

- Bonneville Power Administration, U.S. Federal agency managing sale and transmission of federal power in the Pacific Northwest.

- United States Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. Federal agency managing Libby and many other public works projects

- International Joint Commission, binational commission to prevent and resolve U.S. and Canada disputes over water

- W. A. C. Bennett, Premier of British Columbia who led the development of dams on the upper Columbia and Peace Rivers

- Grand Coulee Dam, the largest dam on the Columbia River

- Kootenai River, upstream Columbia tributary that begins in Canada, enters U.S., and returns to Canada

References

- "The Columbia Basin and the Columbia River Treaty, Canadian Perpectives in the 1990's", 1996 by Nigel Bankes

- "Conflict Over the Columbia, The Canadian Background to an Historic Treaty", 1979 by Neil A. Swainson

- "The Canada/U.S. Controversy Over the Columbia", 1966 Washington Law Review, by Ralph W. Johnson

- "The Columbia River Treaty, the Economics of an International River Basin Development", 1967 by John V. Krutilla

- "The Columbia River Treaty and Protocol, A Presentation", "Appendix", and "Related Documents", 1964 Publications by Canadian Dept. External Affairs and Dept. of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources.

External links

- Binus, Joshua (2004). "Columbia River Treaty: O.K., it's a deal". Oregon Historical Society.

- Text of the Columbia River Treaty Center for Columbia River History,