Watchmaker analogy: Difference between revisions

Chillymail (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

|||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

This motion of the blood, he wrote, |

This motion of the blood, he wrote, |

||

{{Quotation|follows as necessarily from the very arrangement of the parts ''[i.e. the heart, the blood, and body heat]'' ... as does the motion of a clock from the power, the situation, and shape of its counterweights and wheels. |[[Discourse on Method]] | ''translated by [[John Veitch]]'' }} |

{{Quotation|follows as necessarily from the very arrangement of the parts ''[i.e. the heart, the blood, and body heat]'' ... as does the motion of a clock from the power, the situation, and shape of its counterweights and wheels. |[[Discourse on Method]] | ''translated by [[John Veitch (poet)|John Veitch]]'' }} |

||

Descartes had a hydraulic theory of how the brain causes the muscles to move the body. |

Descartes had a hydraulic theory of how the brain causes the muscles to move the body. |

||

Revision as of 17:30, 12 October 2008

The watchmaker analogy, or watchmaker argument, is a teleological argument for the existence of God. By way of an analogy, the argument states that design implies a designer. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the analogy was used (by Descartes and Boyle, for instance) as a device for explaining the structure of the universe and God's relationship to it. Later, the analogy played a prominent role in natural theology and the "argument from design," where it was used to support arguments for the existence of God and for the intelligent design of the universe.

The most famous statement of the teleological argument using the watchmaker analogy was given by William Paley in 1802. Paley's argument was seriously challenged by Charles Darwin's formulation of the theory of natural selection, and how it combines with mutation to improve survivability of a species, even a new species. In the United States, starting in the 1980s, the concepts of evolution and natural selection (usually referred to by opponents as "Darwinism") became the subject of a concerted attack by Christian creationists. This attack included a renewed interest in, and defense of, the watchmaker argument by the intelligent design movement.

The Watchmaker argument

The watchmaker analogy consists of the comparison of some natural phenomenon to a watch. Typically, the analogy is presented as a prelude to the teleological argument and is generally presented as:

- The complex inner workings of a watch necessitate an intelligent designer.

- As with a watch, the complexity of X (a particular organ or organism, the structure of the solar system, life, the entire universe) necessitates a designer.

In this presentation, the watch analogy (step 1) does not function as a premise to an argument — rather it functions as a rhetorical device and a preamble. Its purpose is to establish the plausibility of the general premise: you can tell, simply by looking at something, whether or not it was the product of intelligent design.

In most formulations of the argument, the characteristic that indicates intelligent design is left implicit. In some formulations, the characteristic is orderliness or complexity (which is a form of order). In other cases it is clearly being designed for a purpose, where clearly is usually left undefined.

Arguments that emphasize the appearance of purpose (as in Voltaire, see below), often appeal to biological phenomena. It seems natural to say that the purpose of an eye is to enable an organism to gather information about its environment, the purpose of legs is to enable an organism to move about in its environment, and so on. Even for non-biological phenomena, scientific explanations in terms of purpose were accepted well into the 19th century. Natural phenomena were explained in terms of how they were designed for the benefit of humanity. It was held for instance, that the highest mountains on earth are located in the hottest climates by design — so that the mountains might condense the rain and provide cool breezes where mankind needed them the most.[1] In arguments that emphasize on orderliness or complexity, the argument is often supplemented by a second argument that proceeds this way:

Phenomenon X (the structure of the solar system, DNA, etc.) must be the result of:

- random chance, blind fate, etc.

- natural causes, natural law

- intelligent design

In the case of the watch, for example , neither (1) nor (2) is held to be plausible. The complexity of a watch is taken to mean that it could never have come about through random chance or through any natural process; it must have been designed by an intelligent watchmaker. Similarly (the argument continues), the complexity of X means that it could never have come about through random chance or through any natural process; it must have been designed by an intelligent designer.

This argument is basically a process of elimination: three possible explanations are offered. If the first two (random chance, natural causes) can be ruled out, intelligent design is left standing as the only plausible explanation.

The Achilles heel of the argument is that it fails if there exists a plausible explanation of phenomenon X in terms of natural processes. This makes it vulnerable to advances in science, which has progressively found more and more naturalistic explanations for natural phenomena, and progressively abandoned explanations in terms of teleology. The location of mountains, for instance, is now explained in terms of plate tectonics. The structure of biological organisms is explained in terms of the theory of natural selection. The structure of the solar system is explained in terms of the nebular hypothesis and its refinements.

History

Cicero

Cicero (106 BC – 43 BC) anticipated the watchmaker analogy in De natura deorum, (About the nature of the gods), ii. 34

When you see a sundial or a water-clock, you see that it tells the time by design and not by chance. How then can you imagine that the universe as a whole is devoid of purpose and intelligence, when it embraces everything, including these artifacts themselves and their artificers?

— Cicero, quoted by Dennett 1995, p. 29, (Gjertsen 1989, p. 199)

To Cicero more than one designer was reasonable. The watchmaker analogy was logically an argument for polytheism as much as it was an argument for monotheism.

René Descartes

One of the earliest expressions of the idea that human and animal bodies are clockworks made by God can be found in the work of René Descartes.

Descartes developed the concept of Cartesian dualism, which held that human beings are composed of two distinct substances: matter and spirit. According to this theory, humans have both material bodies and non-material souls, whereas animals have only material bodies but no souls.

Descartes observed that people often reduced their minds to nothing but a function of their body. In Part V of his Discourse on Method (1637), Descartes provided a brief synopsis of his thinking about all aspects of the physical world. This discussion includes a long exposition of his theory about the cause of the circulation of the blood: that the heart functions like a furnace, heating the blood and forcing it to expand out into the circulatory system. This motion of the blood, he wrote,

follows as necessarily from the very arrangement of the parts [i.e. the heart, the blood, and body heat] ... as does the motion of a clock from the power, the situation, and shape of its counterweights and wheels.

— Discourse on Method, translated by John Veitch

Descartes had a hydraulic theory of how the brain causes the muscles to move the body. He explains that the "common sense" causes an animal or human body to move by "distributing the animal spirits through the muscles". See The Description of the Human Body.

Nor will this appear at all strange to those who are acquainted with the variety

of movements performed by the different automata, or moving machines fabricated by human industry, and that with help of but few pieces compared with the great multitude of bones, muscles, nerves, arteries, veins, and other parts that are found in the body of each animal. Such persons will look upon this body as a machine made by the hands of God, which is incomparably better arranged, and

adequate to movements more admirable, than is any machine of human invention.

Descartes then goes on to assert that brute animals have no reason at all, and pauses to consider an objection: that there are some things that animals do better than humans.

It is also very worth of remark that, though there are many animals that

manifest more industry than we in certain of their actions, the same animals are yet observed to show none at all in many others: so that the circumstance that they do better than we does not prove that they are endowed with mind...; on the contrary, it rather proves that they are destitute of reason, and that it is nature which acts in them according to the disposition of their organs: thus it is seen that a clock composed only of wheels and weights can number the hours

and measure time more exactly than we will all our skill.

Note that Descartes is writing before the invention of pocket watches, so his examples of clockworks are clocks powered by weights. Descartes' God is a clockmaker, not yet a watchmaker.

Invention of the Watch

A pocket watch or watch is a small portable clock.

In the early 16th century, the development of reliable springs and escapement mechanisms allowed clockmakers to compress a timekeeping device into a small, portable compartment. In 1524, Peter Henlein created the first pocket watch.

For more information on the early development of watches, see the entry for clock.

Invention of the Orrery

What makes a watch a suitable component in an argument from design is that a watch is composed of clockworks — that is, a watch has many moving parts that interact with each other in complex ways.

An orrery or armillary sphere — a machine that models the solar system and the motion of the planets, using a complex set of clockworks — has a similar appeal. Since the construction of an orrery clearly requires intelligence and design, so (it can be argued) the construction of the actual solar system, whose parts and motions are similar to those of the orrery, must have required intelligence and design.

The first modern orrery was built circa 1704 by George Graham, an English clockmaker and member of the Royal Society. Graham gave the first model (or its design) to the celebrated instrument maker John Rowley of London, who made a copy for Charles Boyle, 4th Earl of Orrery, thus the name.

Joseph Wright's picture "The Orrery" (c. 1766) is an excellent portrayal of both an orrery and the wonder and awe that conveyed.

Robert Boyle

During the 17th century, a new vision of the universe, and of natural law, emerged. In this Cosmology God was no longer seen as constantly active in the world, but as a relatively distant creator being who created the universe, set it in motion, and left it to run under the control of natural laws. Robert Boyle (1627–1691), for instance, argued that the universe

is like a rare clock, such as may be that at Strasbourg, where all things are so skilfully contrived, that the engine being once set a-moving, all things proceed according to the artificer's first design,

and the motions... do not require the particular interposing of the artificer, or any intelligent agent employed by him, but perform their functions upon particular occasions, by virtue of the general and primitive contriance of the

whole engine.

— quoted in G. J. Whitrow, Time in History, Oxford University Press, 1988

In this conception, the universe manifests the wisdom and power of a God who could create a universe so skillfully that, once it had been set in motion, would run properly without any further intervention by its creator. It was felt that a universe that required constant divine tinkering in order to run properly would have reflected badly on its creator's skills, the way that a watch that keeps time poorly would reflect badly on the watchmaker's skills. This increased regard for the laws of nature was one of the reasons for the growing skepticism regarding reports of miracles (that is, reports of events that defied natural law).

Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke (1635–1703) formulated Hooke's law, invented the anchor escapement and may have invented the balance spring before Christiaan Huygens.[2][3]

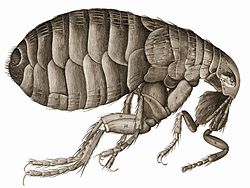

He was also a pioneer in the development and use of the microscope. His revolutionary book Micrographia.[4] featured drawings of life as it had never been seen before — through the lens of a powerful microscope. (The picture on the right is one of many that Hooke drew from a microscope.)

Like Descartes, he compared natural organisms to man-made artifacts, concluding that artifacts paled in comparison with the "Omnipotency and Infinite perfections of the great Creatour"[5]. Hooke compared the way watches were assembled with the workings of the organisms he was examining. He saw these pictures as providing further proof that life was divinely designed.

For, as divers Watches may be made out of several materials, which may yet have all the same appearance, and move after the same manner, that is, show the hour equally true, the one as the other, and out of the same kind of matter, like Watches, may be wrought differing ways; and, as one and the same Watch may, by being diversly agitated, or mov'd, by this or that agent, or after this or that manner, produce a quite contrary effect: So may it be with these most curious Engines of Insect's bodies; the All-wise God of Nature, may have so ordered and disposed the little Automatons, that when nourished, acted, or enlivened by this cause, they produce one kind of effect, or animate shape, when by another they act quite another way, and another Animal is produc'd. So may he so order several materials, as to make them, by several kinds of methods, produce similar Automatons

— Robert Hooke, Micrographia(1664)

Other Writers

The English divine William Derham (26 November 1657 – 5 April 1735) published his Artificial Clockmaker in 1696, a teleological argument for the being and attributes of God. The watchmaker analogy was also made by Bernard Nieuwentyt (1730).

Voltaire

Voltaire (1694–1778) was fond of the argument from design, but also seemed aware of its limitations and treated it gingerly. In his unpublished A Treatise on Metaphysics (1736) Voltaire considered the watchmaker analogy and concluded that it probably indicated the existence of a powerful intelligent designer, but that it did not prove that the designer must be God.

[One way] of acquiring the notion of a being who directs the universe...is by considering ... the end to which each thing appears to be directed... [W]hen I see a watch with a hand marking the hours, I conclude that an intelligent being has designed the springs of this mechanism, so that the hand would mark the hours. So, when I see the springs of the human body, I conclude that an intelligent being has designed these organs to be received and nourished within the womb for nine months; for eyes to be given for seeing; hands for grasping, and so on. But from this one argument, I cannot conclude anything more, except that it is probable that an intelligent and superior being has prepared and shaped matter with dexterity; I cannot conclude from this argument alone that this being has made the matter out of nothing or that he is infinite in any sense. However deeply I search my mind for the connection between the following ideas — it is probable that I am the work of a being more powerful than myself, therefore this being has existed from all eternity, therefore he has created everything, therefore he is infinite, and so on. — I cannot see the chain which leads directly to that conclusion. I can see only that there is something more powerful than myself and nothing more.

— Voltaire, From Chapter 2 of A Treatise on Metaphysics, second version, 1736. Translated by Paul Edwards

Laplace

The watchmaker analogy has been used to support the argument that the complexity of the structure of the solar system can be explained only by an intelligent designer. Today, that explanation has been replaced by the nebular hypothesis.

The account of the interaction between Laplace and Napoleon goes goes, Laplace explained his theory of celestial mechanics to Napoleon. Napoleon, who had not heard God mentioned in the exposition, asked what role God played in Laplace's system. Laplace famously replied, "I have no need of that hypothesis".

Thomas Paine

All the knowledge man has of science and of machinery ... comes from the great machine and structure of the universe. The constant and unwearied observations of our ancestors upon the movements and revolutions of the heavenly bodies ... have brought this knowledge upon earth. It is not Moses and the prophets, nor Jesus Christ, nor his apostles, that have done it. The Almighty is the great mechanic of the creation; the first philosopher and original teacher of all science. Let us, then, learn to reverence our master, and let us not forget the labors of our ancestors.

— Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason, Part II, Section 21

William Paley

Perhaps most famously, William Paley (1743–1805) used the analogy in his book Natural Theology, or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity collected from the Appearances of Nature, published in 1802. In it, Paley wrote that if a pocket watch is found on a heath, it is most reasonable to assume that someone dropped it and that it was made by a watchmaker and not by natural forces.

In crossing a heath, suppose I pitched my foot against a stone, and were asked how the stone came to be there; I might possibly answer, that, for anything I knew to the contrary, it had lain there forever: nor would it perhaps be very easy to show the absurdity of this answer. But suppose I had found a watch upon the ground, and it should be inquired how the watch happened to be in that place; I should hardly think of the answer I had before given, that for anything I knew, the watch might have always been there. (...) There must have existed, at some time, and at some place or other, an artificer or artificers, who formed [the watch] for the purpose which we find it actually to answer; who comprehended its construction, and designed its use. (...) Every indication of contrivance, every manifestation of design, which existed in the watch, exists in the works of nature; with the difference, on the side of nature, of being greater or more, and that in a degree which exceeds all computation.

— William Paley, Natural Theology (1802)

Paley went on to argue that the complex structures of living things and the remarkable adaptations of plants and animals required an intelligent designer. He believed the natural world was the creation of God and showed the nature of the creator. According to Paley, God had carefully designed "even the most humble and insignificant organisms" and all of their minute features (such as the wings and antennae of earwigs). He believed therefore that God must care even more for humanity.

Paley recognised that there is great suffering in nature, and that nature appears to be indifferent to pain. His way of reconciling this with his belief in a benevolent God was to assume that life had more pleasure than pain. (See Problem of Evil).

As a side note, a charge of wholesale plagiarism from this book was brought against Paley in the Athenaeum for 1848, but the famous illustration of the watch was not peculiar to Nieuwentyt, and had been used by many others before either Paley or Nieuwentyt.

Charles Darwin

When Charles Darwin (1809–1882) completed his studies of theology at Christ's College, Cambridge in 1831, he read Paley's Natural Theology and believed that the work gave rational proof of the existence of God. This was because living beings showed complexity and were exquisitely fitted to their places in a happy world.

Subsequently, on the voyage of the Beagle, Darwin found that nature was not so beneficent, and the distribution of species did not support ideas of divine creation. In 1838, shortly after his return, Darwin conceived his theory that natural selection, rather than divine design, was the best explanation for gradual change in populations over many generations.

It can hardly be supposed that a false theory would explain, in so satisfactory a manner as does the theory of natural selection, the several large classes of facts above specified. It has recently been objected that this is an unsafe method of arguing; but it is a method used in judging of the common events of life, and has often been used by the greatest natural philosophers.... I see no good reason why the views given in this volume should shock the religious feelings of any one. It is satisfactory, as showing how transient such impressions are, to remember that the greatest discovery ever made by man, namely, the law of the attraction of gravity, was also attacked by Leibnitz, "as subversive of natural, and inferentially of revealed, religion." A celebrated author and divine has written to me that "he has gradually learnt to see that it is just as noble a conception of the Deity to believe that He created a few original forms capable of self-development into other and needful forms, as to believe that He required a fresh act of creation to supply the voids caused by the action of His laws."

Darwin reviewed the implications of this finding in his autobiography:

Although I did not think much about the existence of a personal God until a considerably later period of my life, I will here give the vague conclusions to which I have been driven. The old argument of design in nature, as given by Paley, which formerly seemed to me so conclusive, fails, now that the law of natural selection has been discovered. We can no longer argue that, for instance, the beautiful hinge of a bivalve shell must have been made by an intelligent being, like the hinge of a door by man. There seems to be no more design in the variability of organic beings and in the action of natural selection, than in the course which the wind blows. Everything in nature is the result of fixed laws.[7]

The idea that nature was governed by laws was already common, and in 1833 William Whewell as a proponent of the natural theology that Paley had inspired had written that "with regard to the material world, we can at least go so far as this—we can perceive that events are brought about not by insulated interpositions of Divine power, exerted in each particular case, but by the establishment of general laws."[8] By the time Darwin published his theory, liberal theologians were already supporting such ideas, and by the late 19th century their modernist approach was predominant in theology. In science, evolution theory incorporating Darwin's natural selection became completely accepted.

Creationist revival of the analogy

In the early 20th century the modernist theology of higher criticism was contested in the United States by Biblical literalists who campaigned successfully against the teaching of evolution and began calling themselves Creationists in the 1920s. When teaching of evolution was reintroduced into public schools in the 1960s they adopted what they called creation science which had a central concept of design in similar terms to Paley's argument. A series of rulings culminating in the Edwards v. Aguillard Supreme court judgement held that the attempts to ban teaching of evolution or to introduce creation science as an alternative were unconstitutional as they violated the establishment clause of the US constitution, which forbids the government from advancing a particular religion. Creation science was then relabelled intelligent design which presents the same analogy as an argument against evolution by natural selection without explicitly stating that the "intelligent designer" was God. The argument from the complexity of biological organisms was now presented as the irreducible complexity argument.[9]

Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins' book The Blind Watchmaker (1986) is a reply to the watch argument. Dawkins argues that highly complex systems can be produced by a series of very small randomly-generated yet naturally selected steps, rather than an intelligent designer.

He further points out the self-refuting nature of the argument: that if complex things must have been intelligently designed by something more complex than themselves, then anything posited as this complex designer (i.e. God) must also have been designed by something yet more complex.

In a Horizon episode also entitled The Blind Watchmaker, Dawkins described Paley's argument "as mistaken as it is elegant". In both contexts he saw Paley as having made an incorrect proposal as to a certain problem's solution, but did not disrespect him for this. In his essay The big bang, Steven Pinker discussed Dawkins' coverage of Paley's argument, adding: "Biologists today do not disagree with Paley's laying out of the problem. They disagree only with his solution."

Challenges to the Watchmaker Analogy

Cultural anthropologists challenge the watchmaker argument both as a 1) faulty analogy and also as a 2) mistaken idea about the matching of people, animals, and plants to their natural settings. That is, a man's mother and father make the man, not a god. And people, animals, and plants have many biological mistakes in their design. [10]

Furthermore, the anthropologists Richerson and Boyd (see below) note that, though one man or woman may make a watch, the know-how that the watchmaker uses consists of the accumulated learning of many generations of technology workers that managed to make minor improvements on the traditions of prior generations. That is, the cultural evolution in watchmaking from generation to generation demonstrates the very Darwinian accumulation of variations between generations in a population that creationists try to use the watchmaker analogy to disprove. It is not even a case of the watchmaker standing on the shoulders of giants. Developing the art of watchmaking is a case of "midgets standing on the shoulders of a vast pyramid of other midgets." [11]

For example, when John Harrison in 1759 created the most accurate watch that had ever been made for use on sailing ships, he used techniques from many generations of traditions in watchmaking and added in "a number of clever tricks borrowed from other technologies of the time, such as using bimetallic strips (you may have seen them coiled behind the needle of oven thermometers and thermostats)" that kept his clocks from changing their rate even when the temperature rose and fell. The fact that so many hundreds of generations of innovations that go into making any good watch leads to claims that "William Paley's famous Argument from Design would better support a polytheistic pantheon than his solitary Christian Creator; it takes many designers to make a watch." [12]

Also, critics of the watchmaker analogy note that it assumes a background of cultural knowledge — familiarity with watches, clockworks, and time-keeping devices in general. It is this familiarity with watches that enables people easily to identify a watch as an artifact of human design. But (the objection goes) we have no analogous knowledge of the culture of an alleged designer of the universe, and thus conclusions about supposed design in nature cannot be drawn on the basis of an analogy to a watch.[13]

In 2005, Paley's watchmaker argument became an issue considered by the court in Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, the "Dover trial," where plaintiffs successfully argued that intelligent design is a form of creationism, and that the school board policy requiring the presentation of intelligent design as an alternative to evolution as an "explanation of the origin of life" thus violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. In his ruling, the judge stated that the use of the argument from design by intelligent design proponents "is merely a restatement of the Reverend William Paley's argument applied at the cell level"[14] and that the argument from design is subjective.[15]

"For human artifacts, we know the designer's identity, human, and the mechanism of design, as we have experience based upon empirical evidence that humans can make such things, as well as many other attributes including the designer's abilities, needs, and desires. With ID, proponents assert that they refuse to propose hypotheses on the designer's identity, do not propose a mechanism, and the designer, he/she/it/they, has never been seen. In that vein, defense expert Professor Minnich agreed that in the case of human artifacts and objects, we know the identity and capacities of the human designer, but we do not know any of those attributes for the designer of biological life. In addition, Professor Behe agreed that for the design of human artifacts, we know the designer and its attributes and we have a baseline for human design that does not exist for design of biological systems. Professor Behe's only response to these seemingly insurmountable points of disanalogy was that the inference still works in science fiction movies. — Ruling, Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, page 81

Deism

The clockmaker hypothesis is a tenet of deism that states that God created the universe, but has not interfered with its operation since then. The analogy is that of a clockmaker who makes a clock, winds it up, and lets it run.

See also

References

- ^ Washington Post "Deja Vu"

- ^ A. R. Hall, "Horology and criticism: Robert Hooke", Studia Copernicana, XVI, Ossolineum, 1978, 261-81.

- ^ Gould, Rupert T. (1923). The Marine Chronometer. Its History and Development. London: J. D. Potter. pp. 158–171. ISBN 0-907462-05-7.

- ^ Project Gutenberg "Micrographia by Robert Hooke"

- ^ Project Gutenberg "Micrographia by Robert Hooke"

- ^ Darwin, C. R. 1872. On the Origin of Species. London: John Murray. 6th edition. p. 421.

- ^ Darwin, C. R. 1958. The autobiography of Charles Darwin 1809-1882. With the original omissions restored. Edited and with appendix and notes by his grand-daughter Nora Barlow. London: Collins, p. 87

- ^ Darwin, C. R. 1859. On the Origin of Species. London: John Murray, p. ii.

Whewell, William, 1833. Astronomy and general physics considered with reference to natural theology. W. Pickering, London, 356 - ^ Scott EC, Matzke NJ (2007). "Biological design in science classrooms". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 Suppl 1: 8669–76. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701505104. PMC 1876445. PMID 17494747.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Richerson & Boyd 2005, pp. 152–153

- ^ Richerson & Boyd 2005, p. 50

- ^ Richerson & Boyd 2005, pp. 51–52

- ^ Refutation of the 'by design' argument for theism

- ^ Ruling, Whether ID Is Science, page 79 Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District 2005

- ^ "It is readily apparent to the Court that the only attribute of design that biological systems appear to share with human artifacts is their complex appearance, i.e. if it looks complex or designed, it must have been designed. (23:73 (Behe)). This inference to design based upon the appearance of a "purposeful arrangement of parts" is a completely subjective proposition, determined in the eye of each beholder and his/her viewpoint concerning the complexity of a system." Ruling, Whether ID Is Science, page 81

External links

- The 'by design' argument for theism

- Full text of Natural Theology; or, Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity

- Intelligent Design Deja Vu What would "intelligent design" science classes look like? All we have to do is look inside some 19th-century textbooks.

- Robert Hooke

- William Paley (1743–1805)

- The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, revised version published in 1958 by Darwin's granddaughter Nora Barlow.

- Recapitulation and Conclusion", By Charles Darwin.

- Natural History Magazine

- The Blind Watchmaker, Richard Dawkins

- Evidence for Jury-Rigged Design in Nature

- Evolution and irrationality

- The Human Eye: A design review (This mentions the birth canal as well.)

- Chaos in the Solar System, by J Laskar

- Index to Creationist Claims

- Stupid Alleged Design of Human Reproduction

- The Watchmaker Analogy Animated and Dramatically Read