Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke (* July 18 jul. / 28. July 1635 greg. In Freshwater , Isle of Wight , † March 3, 1702 jul. / 14. March 1703 greg. In London ) was an English polymath , mainly through the after is known to him named elasticity law . Hooke's work is closely linked to the early decades of the Royal Society . At Gresham College he taught as a professor of geometry and gave the Cutler lectures . After the great fire of 1666 in London , Hooke played a key role in the reconstruction of London as a surveyor and architect . The monument commemorating the fire was designed by him.

Growing up in a royalist and Anglican family home, Hooke was educated at the Westminster School in London after the death of his father . Hooke's practical talent soon became apparent, especially as a draftsman and designer . On the mediation of his teacher Richard Busby he got a job at Christ Church in Oxford . In Oxford Hooke was in the service of a group of naturalists around John Wilkins , who had devoted themselves to experimental nature observation and whose members belonged in 1660 to the group of people who founded the Royal Society . In 1662 the Royal Society appointed Hooke as its curator for experiments .

With the help of optical instruments , which he continuously worked to improve, he observed both the phenomena in the night sky and the world only accessible with the microscope . On the one hand, he discovered the Great Red Spot on Jupiter and , on the other hand, he coined the term “ cell ”. With the drawings made for his main work Micrographia , he opened up insights into the previously largely unknown microcosm . Hooke began regular weather observations on behalf of the Royal Society . He further developed the meteorological measuring devices required for observation and constructed the first forerunner of an automatic weather station . Unlike his contemporaries, Hooke did not see fossils as a mere freak of nature , but saw in them evidence of extinct creatures.

Hooke's contribution to the formation of modern science has long been overshadowed by controversy over the priority of some of his inventions and discoveries. He argued with Christiaan Huygens about which of them built the first spring-driven watch . Isaac Newton refused Hooke any credit for the ideas that led him to the mathematical formulation of his law of gravitation .

No contemporary portrait is known of Hooke . His remains have been in a mass grave in the City of London Cemetery in Manor Park since 1891 .

Childhood on the Isle of Wight

Robert Hooke was born on July 18, 1635 in the coastal town of Freshwater on the Isle of Wight . He was the fourth and last child of Reverend John Hooke († 1648) and Cecily Gyles († 1665). His father presumably studied at the University of Oxford and was ordained there . Around 1615 he entered the service of Sir John Oglander (1585-1655), the governor of the Isle of Wight, to teach his son George in Brading . There John Hooke married Cecily Gyles in 1622. In addition to Robert, he had three other children with her: Anne († 1661), Katherine (* 1628) and John (1630–1678). Around 1625 his father became a curate of the Anglican All Saints Church in Freshwater.

The little known about Hooke's childhood comes from his fragmentary autobiography , begun on April 10, 1697 , which his first biographer Richard Waller had before him. Hooke recalled a carefree childhood marred by occasional attacks of stomach upsets and headaches. He made mechanical toys, disassembled an old copper clock into its components and made the individual parts out of wood. He also made a nearly three-foot-long, buoyant sailing ship model, whose cannons are said to have even been able to fire. During a visit to the miniature painter John Hoskins (around 1590–1664 / 5) Hooke's drawing talent was revealed.

Until November 1647, the English Civil War , which began in 1642, had little impact on the lives of the mostly royalist residents of the Isle of Wight. On November 11, 1647, King Charles I escaped his guards in London and fled to the island, where he arrived two days later. In Newport , surrender negotiations between the royalists and representatives of parliament began soon afterwards .

On September 23, 1648 Hooke's father drew up his will and designated his friends Nicholas Hockley, Robert Urrey and Cardell Goodman (around 1608-1654) as his administrators. Shortly after Charles' surrender on October 8, 1648, Hooke's father died. His funeral took place on October 17, 1648. He left his son Robert £ 40 , his best trunk, and all of his books. Added to this was £ 10 from the estate of Robert Hooke's grandmother Ann Giles.

Training in London and Oxford

Robert Hooke came to London at the age of 13. How he got there is not known. He may have traveled with Cardell Goodman or with that of the miniature painter John Hoskins. In London he was initially a student of the painter Peter Lely for a short time . Samuel Cowper , a nephew of Hoskins, is also said to have taught him. At the end of January 1649, Hooke was in the care of Richard Busby (1606–1695), in whose household he lived and who taught him. Busby was headmaster of the Westminster School since 1638 . During his time in Westminster, Hooke learned Latin fluently , acquired a good knowledge of Greek and was able to acquire some Hebrew . He showed a talent for mathematics and special skills as a draftsman. He also learned how to use the lathe and how to play the organ .

In 1653 Hooke left Westminster School in London to continue his education at Christ Church in Oxford . Westminster School had a close relationship with Christ Church, and he met some of his classmates there. Richard Lower had been studying there since 1649, and John Locke had enrolled a year earlier. At Oxford Hooke was initially a scholarship holder (Servitor) of a “Mr. Goodman ”and was supposed to play the organ as a choir student . Brokered by Busby, he lived in the household of Thomas Willis from 1654 and assisted him with his chemical experiments in the Beam Hall in Oxford's St. John's Street. Willis was a member of a group of naturalists around the warden of Wadham College , John Wilkins . This group had dedicated itself to the experimental observation of nature, as suggested by Francis Bacon in Novum Organum in 1620 . This group included Jonathan Goddard , John Wallis , William Petty , Christopher Wren and Seth Ward , among others . In 1648 Wilkins had written Mathematical Magick, a work that was widely regarded, which dealt with the principles of levers, rollers, gears and worms and in which he speculated about flying machines and a possible journey to the moon. During this time Hooke constructed a flying machine and improved the accuracy of the pendulum clocks for Seth Ward , which he used for his astronomical observations.

As early as 1653 Wilkins had invited Robert Boyle to Oxford, who made no headway with his chemical experiments in Dublin . Boyle finally settled in Oxford in the fall of 1655, and from the following year Hooke was an assistant to Boyle's household. Boyle wanted, inspired by Otto von Guericke's work, to construct his own improved " air pump ". With Hooke's significant participation, the difficult undertaking finally succeeded around 1659. Together, Boyle and Hooke carried out investigations into the properties of air. Boyle published the results of these experiments, which were completed in December 1659, in The Spring of the Air , published in 1660 , in which he described 43 experiments on the construction and use of the new air pump and in the foreword of which he expressly acknowledged Hooke's merit.

On July 31, 1658, Hooke was enrolled at Oxford University . However, he did not earn a degree while at Oxford. After 1659, the members of the Oxford group around Wilkins gradually moved to London.

Curator of the Royal Society

When the Royal Society was founded on November 28, 1660 , the twelve founding members included Robert Boyle, William Petty, John Wilkins and Christopher Wren, four members of the Oxford Group. Boyle's new "Pneumatic Engine" constructed in Oxford was used in numerous experiments in the early days of the Royal Society . As Boyle's assistant, Hooke was responsible for conducting these experiments. His name is first mentioned in the files of the Royal Society on April 10, 1661 in connection with his first scientific work, An Attempt for the Explication of the Phaenomena, observable in an Experiment published by the Honorable Robert Boyle , from 1661 . Hooke tried to explain the phenomena described in Boyle's The Spring of the Air as the 35th experiment on the capillary action of water in thin tubes. With his practical skills, Hooke quickly gained recognition from the members of the Royal Society . On November 12, 1662, Robert Moray proposed to employ Hooke as "Curator of Experiments" of the Royal Society . Hooke was unanimously elected to this position by members of the Society. His task as curator was to prepare and carry out three to four experiments for the weekly meetings of the society and to support other members in carrying out experiments. On June 3, 1663 Hooke was admitted to the Royal Society and exempted from the contribution that a member of the society normally had to pay.

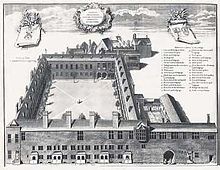

The members of the Royal Society endeavored to provide Hooke with a secure income. They considered a professorship at Gresham College . It was a hindrance that Hooke had not obtained a degree. Through the mediation of the Chancellor of Oxford University Edward Hyde he was awarded the title of Magister Artium in September 1663 . With two professorships at Gresham College indicated at this time the need for a replacement. When the astronomy professor Walter Pope (around 1627-1714) went abroad for two years in April 1663, the professor of geometry Isaac Barrow initially took over Pope's teaching duties. Barrow was finally appointed to the newly established Lucasische Chair of Mathematics at the end of 1663 . When Barrow's chair was replaced on May 20, 1664, Hooke was defeated by the doctor Arthur Dacres (1624–1678) despite the support of the Royal Society . After this defeat, John Graunt and William Petty approached John Cutler with the request to sponsor a lecture for Hooke. In June 1664 Cutler complied with this request and donated the Cutler Lecture, endowed with 50 pounds per year, for Hooke for life. On July 27, 1664, the Royal Society officially regulated Hooke's financial remuneration as a curator and also guaranteed him accommodation in or near Gresham College. In September Hooke moved from the home of Boyle's sister Lady Ranelagh (1614-1691) and moved into his room at Gresham College, which he lived until his death. In the summer of 1664, the Royal Society learned that Dacre's election as geometry professor had been rigged by London Mayor Anthony Bateman . The Royal Society urged Dacres to resign. On March 20, 1665, Hooke finally became professor of geometry at Gresham College. Prior to that, he had already given the astronomical lectures there in the 1664/1665 semester on behalf of Walter Pope. With his three positions as curator of the Royal Society as well as professor of geometry and Cutler professor at Gresham College, Hooke was financially secure.

After the death of Henry Oldenburg , Hooke was elected one of the two secretaries of the Royal Society on October 25, 1677 . He performed this function in addition to his duties as a curator until 1682.

Observer, experimenter and inventor

Micrographia

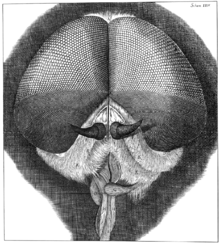

On April 1, 1663, Hooke received a request from the Royal Society to contribute to each of their weekly meetings an observation made with his compound reflected light microscope . During the year he presented the members with numerous drawings of objects from the animate and inanimate world. Objects observed included the point of a needle , the edge of a blade , Venetian paper , petrified wood , a mold, and the eggs of the silk moth . His contemporaries found the depictions of the compound eye of a fly , a spider and a mite to be particularly unusual . Cork was also among the materials Hooke studied . For the cavities he observed in cork under the microscope, he coined the term cell for " cell ".

In the summer of next year the Royal Society decided to have Hooke's observations printed on their behalf. His work received the title Micrographia and was after John Evelyn's Sylva, or Discourse on Forest Trees, the second work with the printing permission of the Royal Society . Among the sixty of Hooke's "observations" were some speculations, from which the Royal Society distanced itself and asked Hooke to clarify this in a foreword.

One of these speculations was Hooke's theory of matter . He assumed that matter was made up of invisibly small, vibrating particles. His thesis was based on an analogy to the relationship found by Marin Mersenne between the frequency and the pitch of a vibrating string . Just as the frequency generated by a string depends on its length, thickness and tension, the oscillation frequency of the matter particles depends in the same way on material, shape and quantity. The different appearance of solid, liquid and gaseous bodies can be explained by the different oscillation frequencies of their particles.

astronomy

Hooke was an active observing astronomer who was also interested in improving the observation instruments available to him, particularly telescopes and devices for measuring angles . One of his supposedly first writings, the Discourse of a new Instrument to make more accurate Observations in Astronomy, Than Ever Were Yet Made, from 1661, which has not yet been found, dealt with this topic.

In April 1663, the Royal Society decided to pinpoint the positions of the zodiac stars . Together with Wren, Hooke was responsible for measuring the stars in the constellation Taurus . A drawing of the Pleiades that was created in the process found its way into his work Micrographia . He discovered a fifth trapezoidal star in the constellation Orion and examined the star Mesarthim in the constellation Aries, one of the first double stars ever observed . On May 9, 1664, Hooke discovered the Great Red Spot on Jupiter . He observed its movement and concluded that Jupiter, like the earth , must rotate around its axis . Giovanni Domenico Cassini was able to estimate the rotation time of Jupiter shortly afterwards. Together with Wren, Hooke also examined the orbit of comet C / 1664 W1 , which appeared in December 1664, during this time . In March 1666, he discovered that the position of some objects on Mars had shifted slightly. He succeeded in demonstrating the rotation of a second planet . Again it was Cassini who shortly thereafter estimated the rotation period. Richard Anthony Proctor used the drawings Hooke made and his observational data more than two hundred years later in his new determination of the duration of the Martian day.

In the sixtieth and last "observation" of Micrographia entitled Of the Moon (Over The Moon) Hooke wrote his thoughts on the origin of with craters covered lunar surface down. He developed two theses and tried to confirm them with laboratory experiments. His first thesis attributed the observable shape of the moon's surface to volcanic activity , the second explained it to the impact of objects on the moon. The experiments carried out by Hooke allowed both explanations equally. However, since he could not explain where objects hitting the moon could have come from, he rejected the second thesis. In this context, he also speculated whether the earth's surface could be shaped similarly.

Hooke's efforts to prove the star parallax and thus to provide experimental evidence for the motion of the earth around the sun go back to the summer of 1666. On October 22, 1668 he reported to the Royal Society that he had built a zenith telescope in Gresham College for this purpose . Hooke called this telescope the "Archimedean Engine", alluding to Archimedes ' saying that he could move the earth with a lever . For his observations he selected the star γ Draconis, which is at its zenith in London . From four measurements taken from July 1669 to October 1670, in his An attempt to prove the motion of the earth from observations, he derived a parallax of 30 arc seconds - a value that, as it turned out many years later, was far too large, but has long been recognized as evidence of star parallax.

Hooke constructed a helioscope , a telescope for observing the sun , in which glass panes and prisms dampen the sunlight. One of his unrealized ideas was to have an equatorially mounted telescope controlled by a pendulum clock in order to compensate for the rotation of the earth during observations .

Meteorology

On September 2, 1663, the Royal Society commissioned Hooke to keep daily weather records . The members of the Royal Society hoped to be able to develop methods for weather forecasting on the basis of this information . Just a month later, Hooke presented his weather observation method, which includes all the basics of modern meteorology .

Hooke improved or invented numerous meteorological instruments . In his work Micrographia he had proposed a procedure for a temperature scale in which the zero point was set to the freezing point of water . After a successful demonstration of the method in early 1665, the Royal Society adopted Hooke's method as the standard for their temperature measurements. The wheel barometer developed by Hooke transferred changes in air pressure to a pointer with the help of a weight floating on a mercury column, thus making it easy to read the value. In his Micrographia he also described a hygrometer , which also a pointer instrument was and for measuring the hygroscopic induced change in length of the awns of the wild oats used. It worked in a similar way to the hair hygrometer that was later used . An improved anemometer by Hooke , which used the deflection of a wind plate , was the most widely used device for determining wind speed for almost 200 years .

Since the end of 1663, Wren and Hooke worked together on a " weather clock " that was supposed to record meteorological data controlled by a pendulum clock and the development of which dragged on over many years. It was only on May 29, 1679 that Hooke was able to present a copy he had designed to the Royal Society . This first automatic weather station recorded the wind direction , wind speed, amount of precipitation , temperature , humidity and air pressure on strips of paper.

geology

As a child, Hooke had roamed the eroded coastline of the Isle of Wight and was interested in the fossils embedded in the limestone cliffs . In order to clarify some family matters after his mother's death in June 1665, he stayed on the island again after a long absence from the beginning of October 1665 to January 1666. He used this time to study the geological composition of the island and to collect fossils. In 1667 he began before the Royal Society with a series of lectures on geology , which extended intermittently for more than thirty years and which were published as Discourses of Earthquakes (speeches on earthquakes) in 1705 in his posthumous writings.

In contrast to almost all of his contemporaries, for Hooke fossils were not a freak of nature , but fossilized living beings. Since some of the fossils he examined did not resemble any of the existing living things, he considered that they must be extinct creatures. He speculated on whether changes in climate, soil, and diet could lead to the formation of new species . Hooke's observations made it clear that the earth must be older than the theologian James Ussher's age of about 6000 years and that the duration of the biblical flood was far too short to explain the geological shape of the earth. Since, according to his understanding, fossils were formed by sedimentation processes in the sea, he looked for processes that could explain the upward movement of these layers and considered earthquakes to be a possible explanation. Hooke continued to speculate that there was a cyclical exchange of land and sea. He assumed that the change in the pole evacuation force associated with the polar migration of the earth's axis would ensure this area exchange.

Ellen T. Drake, who examined Hooke's geological ideas, assumes that his considerations had an influence on Nicolaus Steno and James Hutton , both of whom are referred to as the "father of geology". Arthur Percival Rossiter even called him in 1935 the "first English geologist".

City surveyor and architect

In early September 1666, 80 percent of the City of London was destroyed in a three-day fire . On September 19, 1666 Hooke presented a "model" for the reconstruction of the city. Like five others, his plan was discarded for reasons of cost and time. The City of London appointed him on October 4, 1666 to a six-member commission for the reconstruction. Their first task was to make recommendations for the widening of the streets and the removal of alleys, which had been discussed since 1662. From October 31, 1666, the commission began to draw up building regulations and devoted itself to the regulations associated with the reconstruction. This was followed by numerous consultations between the Commission and the City and the Privy Council . During this time, Hooke, on behalf of the Royal Society, examined the resilience of the bricks made from various clay soils from which the new houses were to be built. On February 8, 1667, King Charles II gave his approval to the first Rebuilding Act and confirmed the new building regulations also worked out by Hooke, but reserved his approval for the planned road widening. The Court of Common Council presented the relevant laws on road widening on March 13, 1667 and decided on the same day with Peter Mills (1598–1670), Edward Jerman (around 1605–1668), Hooke and John Oliver (1616 / 1617– 1701) to order four surveyors . The next day, Hooke and Mills were sworn in in the Court of Aldermen . Jerman never was a surveyor. Oliver was sworn in on January 28, 1668.

Hooke and Mills began on 27 March 1667 of Fleet Street with the staking of new roads. Most of this work was done within the next nine weeks. A Common Council law passed on April 29, 1667 finally established the obligations of all residents who wanted to rebuild their homes. Hooke and Mills were responsible for surveying the site and collecting the Common Council-imposed rebuilding fees. These fees were recorded in day books, the entries of which extend over the period from May 13, 1667 to July 28, 1696 and document 8,394 start-ups. Most of the surveying work was completed by the end of 1671, when 95 percent of the building site had been surveyed. Another obligation of Hooke and the other surveyors was to set and certify an appropriate amount of money for the land loss suffered by the owners through road widening or other reconstruction work. From March 31, 1669, Hooke and Mills therefore had to attend the weekly meetings of the City Lands Committee responsible for disputes .

In 1670 the City Churches Rebuilding Act was passed, which stipulated the rebuilding of 51 Parish churches. Christopher Wren, who was responsible for the implementation, therefore employed Hooke in addition to his already existing obligations as “First Officer” of his architectural office. Together with Wren, Hooke monitored the construction progress and began designing the first buildings himself. These include the Monument to the Great Fire of London , the Royal College of Physicians , the Bethlem Royal Hospital and numerous private homes.

Controversy

About the cause of the colors

At the beginning of 1672, Isaac Barrow drew the attention of the Royal Society to his protégé Isaac Newton and presented his novel reflecting telescope . Less than a month later, Henry Oldenburg received a letter from Newton in which he presented his ideas about the nature of light , refraction and colors . Newton explained that white light is a mixture of all rainbow colors, which is split into colors when it passes through an optical prism as a result of the different degrees of refraction of the individual components. Newton also believed that light was made up of small particles and did not propagate as a wave . Hooke and others were invited to comment on Newton's letter, but only Hooke complied a week later.

In his work Micrographia , Hooke described color phenomena and colored rings that he had observed in the mineral muscovite , on oyster shells and other thin layers , and which also appeared when he pressed two pieces of glass together. He also explained how the observed colors are created. In his criticism, Hooke repeated the thesis already cited in the Micrographia that “light is nothing more than a shock wave that propagates through a homogeneous, uniform and transparent medium, and that color is nothing but the disruption of this light [...] through refraction . ”Newton's letter was published in the Philosophical Transactions , but Hooke's comment was not. After several drafts and at Oldenburg's insistence, Newton, surprised and excited by the harsh criticism, finally sent his reply to the Royal Society three months later, in which he sharply rebuked Hooke and accused him of a lack of understanding . Newton's letter, read to the Royal Society on June 12, 1672 and then published in the Philosophical Transactions , was the starting point of a tension between Hooke and Newton that lasted for many years.

In 1675 Newton asked for the support of the Royal Society when carrying out a critical experiment, the result of which one of his other critics, the Jesuit Francis Linus (1595–1675), questioned . If desired, he would send another paper on his color theory to society. At the beginning of December 1675 Newton sent Oldenburg a treatise entitled A Hypothesis to Explain the Properties of Light, as discussed in my various papers . This was read out on December 9 and 16, 1675. Towards the end of the paper, Newton referred to a novel light phenomenon that Hooke had observed in the spring, which Hooke called "inflexion" - that is, diffraction . Newton saw in it only another form of refraction and, moreover, doubted the news of the observation, since the phenomenon had been described ten years earlier by Francesco Maria Grimaldi . Hooke, who felt himself attacked by Newton again, announced to the assembled society that everything important was already in his micrographia and that Newton had only worked out a few details. Oldenburg immediately reported this to Newton and read his reaction to Hooke's remark on January 20, 1676 before the Royal Society . According to Newton, Hooke only embellished René Descartes ' theory of light. His theory, however, is completely independent and he “should therefore prove that the hypothesis I wrote is not only in the result - as he assumes - but in all parts of his micrographia . Then he should also please prove what comes from himself. ”Hooke, surprised by Newton's sharp tone, suspected that Oldenburg had misrepresented his reaction, and wrote a letter to Newton the same day. In it he expressly paid tribute to Newton's services and asked him for a direct, private exchange of her thoughts on natural philosophy. Newton replied politely, acknowledging Hooke's contributions to optics, but emphasizing his own accomplishments: “ If I've looked further, it's because I'm standing on the shoulders of giants. "

About the invention of the spring-driven clock

On February 18, 1675, Oldenburg read an excerpt from a letter from Christiaan Huygens before the Royal Society , which was immediately intended for publication in the Philosophical Transactions . Huygens announced that he had invented a new, compact watch with a spring balance that had a previously unattained accuracy . Hooke, who had heard of this letter the day before, reacted violently and claimed the priority of this invention for himself. As early as the 1660s, he introduced the members of society to some clocks driven by a spiral spring .

The development of accurate clocks that are insensitive to external influences was an important step towards solving the problem of determining the geographical length of ships on the oceans. Hooke said he had developed an improved pendulum clock as early as 1658 , which he believed would help solve this problem. At the end of 1663 or beginning of 1664 Boyle arranged a meeting with Moray and Brouncker at which the conditions for a patent for Hooke's pendulum clock were to be negotiated. However, Hooke did not agree to the proposed conditions, since the basic principle he had developed was not to be protected, but any further improvement would also enjoy patent claims. Huygens had a pendulum clock patented in 1657, which had a significantly improved rate accuracy compared to conventional clocks. When Huygens was in London in 1661, the Royal Navy became interested in his invention and experimented with his pendulum clock for four years. An improved version of Huygens pendulum clock was granted a patent negotiated by Robert Moray in 1665. The resulting income was shared by Huygens with the Royal Society .

Henry Oldenburg, secretary of the Royal Society and long-time correspondent Huygens, worked vehemently for Huygens to be granted an English patent for his novel watch. Immediately after hearing Huygen's letter, Hooke and the London watchmaker Thomas Tompion began to manufacture a watch with a spring balance that worked according to his ideas. In April 1675, Jonas Moore (1617–1679), who as Surveyor-General of the Ordnance was responsible for British military research and development, arranged an audience for Hooke and Tompion with the English king, where they presented the prototype of the clock to him. The clock presented to the king bore the inscription " R. Hooke invenit 1658. T. Tompion fecit 1675. ", invented by R. Hooke 1658 and manufactured by T. Tompion 1675. Oldenburg urged Huygens to send a functioning sample clock to England. The copy sent by Huygens to Brounker in June proved to be unreliable, but Hooke and Tompion also had to repeatedly make corrections to the watch tested by the king.

In order to prove his claim to priority, Hooke inspected the files of the Royal Society , but could not find in them the demonstrations of his spring-driven watch. He suspected Oldenburg of manipulation and betrayal and made this publicly known in his Cutler lectures Helioscopes and Lampas . The Council of the Royal Society , which saw their reputation endangered by the patent dispute, supported Oldenburg and reprimanded both Hooke and John Martyn, the printer of the Royal Society . When Hooke was elected Secretary of the Royal Society after Oldenburg's death in autumn 1677 , he was able to inspect Oldenburg's correspondence. In it he found two letters from 1665, one from Huygens to Oldenburg and one from Moray to Huygens, from which it emerged that Huygens received important information about Hooke's clock experiments from both of them.

About the description of planetary motion

For Hooke, gravity embodied one of the most universal principles. In one of his first experiments as curator of the Royal Society at the end of 1662, he investigated whether a weight difference could be measured in a body at different heights , but could not prove any. A little over three years later he repeated similar experiments in a deep well near Banstead in the County of Sussex , again without result. Another idea by Hooke, which originated in 1666, was to use the period of oscillation of a pendulum to demonstrate that the force of gravity was dependent on height, but it did not lead to any measurable result.

As an astronomer, Hooke was interested in how the observable movements of the heavenly bodies could be explained. On May 23, 1666 he proposed to the assembled members an interpretation for the planetary orbits described by Johannes Kepler . The movement of the planets can be imagined as a superimposition of an inert straight movement with a curvature directed towards the center of the sun due to the gravitational pull of the sun. In his Cutler lecture of 1674, Hooke further concretized his idea of the workings of gravity. The effect between the celestial bodies is immediate and the closer they are, the stronger it is.

At the end of November 1679, Hooke, in his capacity as the new secretary of the Royal Society, again contacted Newton and asked him to resume his earlier correspondence with the Society. In passing, Hooke asked Newton what he thought of his thesis that planetary motion was composed of a tangential motion and an attractive motion to the central body . Newton replied that he had no knowledge of Hooke's thesis and was currently not interested in any natural-philosophical exchange of ideas. Despite Newton's initial negative attitude, an exchange of ideas comprising seven letters developed between November 24, 1679 and December 3, 1680, which is one of the most influential in the history of physics and in the course of which Hooke Newton announced on January 6, 1680, “My It is assumed, however, that the attraction is reciprocally quadratic to the distance from the center [...] ”.

In January 1684, following a meeting of the Royal Society in a London coffee house , Hooke, Wren and Halley discussed the question of whether the elliptical shape of the planetary orbits could be caused by a force that decreases with the square of the distance from the sun . Hooke claimed to both of them that he could prove it. When Halley was visiting Newton in Cambridge six months later , he asked him what shape the planetary orbits would have under the action of such a force. Newton promptly replied "an ellipse" and informed Halley that he had made a calculation. He promised Halley to send it to him. In November Halley Newton received Newton's nine-page treatise De motu corporum in gyrum (On the movement of bodies on a path) , which is a forerunner of Newton's principal work Principia Mathematica , published in the summer of 1687 . Halley, who funded the printing of Newton's Principia and oversaw the printing, informed him in May 1686 that Hooke was expecting an appropriate mention for his discovery. In his letters to Halley, Newton gave several arguments to justify why he was denying Hooke the recognition he wanted, and from his manuscript he erased all the passages in which he had still made respectful reference to Hooke.

About the accuracy of telescopic observations

At the end of 1685, when the honorary secretaries Francis Aston (1644–1715) and Tancred Robinson (around 1657–1748), who were responsible for the Philosophical Transactions , resigned, the dispute between Hooke and Johannes Hevelius about the usefulness of free-eyed astronomical observations culminated for years . After Hooke received a copy of Hevelius' Cometographia in 1668 , the two were in contact. In return, Hooke sent him a description of his telescope. He tried to convince Hevelius, who observed exclusively with the naked eye, that the accuracy of telescopic observations is many times higher. In 1673 Hevelius published his work Machina Celestis , in which he described his observation instruments and which contained part of his decades of observation results. His work was received with admiration by many members of the Royal Society , including Edmond Halley . Hooke, on the other hand, sharply criticized Hevelius' work in his Cutler lecture Animadversions on the First Part of the Machina Coelestis the following year. On January 17, 1674, he demonstrated to the members of the Royal Society that the human eye can only resolve angular distances of about one angular minute . Hevelius, however, claimed that his naked-eye observations were accurate to within a few arc seconds . In the fall of 1685, an anonymous review of Hevelius' last work, Annus Climactericus , appeared in the Philosophical Transactions , probably written by John Wallis . The discussion contained excerpts from numerous letters Hevelius openly questioned Hooke's competence as an astronomer . The personal attacks on Hooke and their publications in the Philosophical Transactions finally led to a scandal , as a result of which Edmond Halley was hired as the paid clerk of the Royal Society and entrusted with the publication of the Philosophical Transactions .

Last years

The priority disputes made Hooke more cautious. For example, he encoded the only discovery still associated with his name in 1676 at the end of his treatise A Description of Helioscopes as the following anagram “ceiiinosssttuu”. Only two years later did he reveal the wording of Hooke's law in Lectures de Potentia Restitutiva : "ut tensio sic vis" - like stretching, so is strength. At the end of 1682 Hooke was relieved of his duties as secretary of the Royal Society , but was still a member of the council several times until 1699. In 1681 he invented the iris diaphragm and in 1684 devised a system for the optical transmission of messages .

In 1687, Hooke's niece Grace, who had run his household for almost 15 years and was his lover, died. Her death brought about a profound change in his personality. The well-groomed, sociable and cosmopolitan Hooke became melancholy and cynical. After the Glorious Revolution of 1688/1689 he also had to watch how his opponents Newton and Huygens gained more and more influence. For his contribution to the establishment of the Almshouses Aske's Hospital in Hoxton , Hooke was awarded the title of Doctor of Medicine by the Archbishop of Canterbury John Tillotson (1630-1694). He took the necessary oath on December 7, 1691 before Charles Hedges (1650-1714) in Doctors' Commons . Until recently he continued his lectures sporadically. The content of his discourses, however, became increasingly metaphysical . In 1692 Hooke gave a lecture on the Tower of Babel and in the following year on Ovid's Metamorphoses . In 1693 he finally ended his work for Wren because he could no longer climb the scaffolding.

In the months before his death, Hooke's health, which had suffered in the past few years from his only milk and vegetable diet and ongoing self-medication, deteriorated rapidly. He died on March 3, 1703 in his rooms at Gresham College. His friend Robert Knox and his assistant Harry Hunt (1635-1713) laid out the body and sealed its rooms to prevent theft. Hooke was buried in St. Helens Church on Bishopsgate Street. His remains were in 1891 together with those of another of about 300 people in a mass grave in the cemetery of the city of London in Manor Park reburied , the church was rebuilt as the floor.

Reception and aftermath

rehabilitation

In 1705, Richard Waller , a close friend of Hooke's, published his most important posthumous writings. They were preceded by a brief biography, based in part on Hooke's fragmentary autobiography. In 1726 William Derham assembled numerous small contributions by Hooke in another estate volume. The biographical data collected by John Aubrey , also a good friend of Hookes, for the antiquarian Anthony Wood (1632–1695) were not used in the first edition of Woods Athenae Oxonienses (1691–1694). Only in the posthumously published second edition of 1721 is there a short entry on Hooke's life. Andrew Clark published a complete edition of Aubrey's manuscripts in the Bodleian Library in 1898 under the title Brief Lives .

Until the 1930s, Hooke was largely forgotten. It was only in the run-up to the 300th anniversary of his birth that his contributions to modern science were first processed. From 1930 to 1938 Robert Gunther made Hooke's hard-to-access writings available for research in several volumes of his Early Science in Oxford . In 1935, Henry William Robinson and Walter Adams published large parts of Hooke's diary, which was found in Harlow in 1891 and purchased by the Corporation of the City of London . These diary entries covered the period from 1672 to 1680. In the same year Gunther added to this edition the publication of further entries from the years 1688 to 1690 and 1692 to 1693.

After World War II , Edward Andrade's haunting Wilkins lecture on December 15, 1949 at the Royal Society rekindled interest in Hooke. A first detailed biography, written by Margaret Espinasse, appeared in 1956. Access to his extensive work for the Royal Society was given in 1968 by the reprint of Thomas Birch's four-volume work The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge , which details the first Logged decades of the work of the Royal Society, facilitated. In the 1960s and 1970s, historians examined the early history of the Royal Society from new, broader angles. Michael Hunters wrote a book about the early members of the Royal Society, REW Maddison, Jim Bennett and Richard S. Westfall wrote extensive biographies on Boyle, Wren and Newton, including Hooke's letters to Boyle, Newton, Oldenburg, Flamsteed, Huygens and others were published. Numerous individual studies examined Hooke's contributions to the development of scientific instruments (barometer, microscope, telescope, timepiece), his achievements as an architect and cartographer and as a researcher in the fields of optics, magnetism, mechanics, chemistry, geology and his interest in natural philosophy in a universal language, a "Philosophical Algebra".

The British Society for the History of Science organized a first scientific conference devoted exclusively to Hooke, held July 19-21, 1987 at the Royal Society in London. Interest in Hooke continued to grow in the 1990s. For example, in a book published in 1996, Ellen Tan Drake examined its role in establishing geology. In his dissertation, completed in 1999, Michael Cooper highlighted his extensive work as a surveyor and architect in the reconstruction of London.

The scientific examination of Hooke's achievements and his recognition as an important naturalist of his time on the 300th anniversary of his death in 2003 reached its preliminary climax. Two biographies about him were published by Stephen Inwood and Lisa Jardine. On the afternoon of March 3, 2003 , a memorial service was held in the only fully preserved building designed by Hooke, Willen Parish Church in Milton Keynes . From July 6-9, 2003, the Royal Society and Gresham College hosted an international conference entitled Restoring The Reputation Of Robert Hooke , hosted with the assistance of the Royal Academy of Engineering . A symposium on Robert Hooke and the English Renaissance was held on October 2, 2003 under the auspices of Christ Church , which also dealt with new insights into Hooke's work.

Portrait

No contemporary portrait of Robert Hooke has yet been found. On July 5, 1710, the Frankfurt alderman and lawyer Zacharias Konrad von Uffenbach (1683–1734) visited the premises of the Royal Society, which was still in session at Gresham College, and noted in his travel report: “At last we were assigned the room and the Society together come care. It is very small and bad, and the best of all is the many portraits of the members, the strangest of which is that of Boyle and Hoock. ”This is one of the few indications that such a portrait must have actually existed. It was probably lost when the Royal Society moved to Crane Court, which was supervised by Newton .

In its July 3, 1939 issue, Time published a portrait with the caption Scientist Hooke . However, research by Ashley Montagu showed that this is not a portrait of Hooke.

During her research for her book The curious life of Robert Hooke in the holdings of the Natural History Museum, the British historian Lisa Jardine came across a portrait entitled " John Ray " and attributed to the painter Mary Beale (1632 / 3-1699), of which turned out to be not the English naturalist. On the basis of further evidence, for example there is evidence in Hooke's diary that Robert Boyle was portrayed by Mary Beale, Lisa Jardine concluded that it must be the lost portrait of Robert Hooke. Shortly after the publication of her book, for which this portrait was used as a book cover , William B. Jensen of the University of Cincinnati was able to assign the portrait to the Flemish Johan Baptista van Helmont on the basis of two copper engravings .

Around 2003, a document by Hookes, dated February 2, 1684/5, was discovered in the Isle of Wight County Record Office, which, in addition to his signature, also bears an imprint of a seal depicting a man in profile . It is unclear whether this could be a portrait of Hooke.

On the occasion of the activities for the 300th anniversary of Robert Hooke's death, a competition was held under the title Portraying Robert Hooke - Recreating the Hidden Genius , in which a new, modern portrait of Robert Hooke was to be created. The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors and the Royal Society had donated a prize of 500 pounds for this purpose. The winner was the Hooke portrait by Guy Heyden.

estate

Robert Hooke died without a signed will . In a later found draft will he planned to divide his fortune among four friends, but did not yet use any names. The antiquarian and topographer Thomas Kirke (1650-1706) speculated in a letter to Godfrey Copley that these were Christopher Wren, John Hoskyns (1634-1705), Robert Knox and the instrument maker Reeve Williams (? -1703). Hooke left a substantial fortune of £ 9,580, of which £ 8,000 was kept in cash in a simple wooden chest. His property went to relatives from the Isle of Wight: his cousin Elizabeth Stephens, a daughter of Hooke's father's brother, and their daughter Mary Dillon, and Anne Hollis, a daughter of Hooke's mother's brother. In 1707 there were disputes over Hooke's inheritance when Anne Holli's brother, Thomas Gyles, who had emigrated to Virginia , learned of Hooke's estate and sued in court.

Hooke's library consisted of over 500 folio volumes , 1,310 quarto volumes, 845 volumes in octave format and 393 volumes in duodec format . It was auctioned on April 29, 1703 for a sale of £ 250.

Hooke's unpublished writings passed into the possession of Richard Waller , who also received his diary from Elizabeth Stephens in December 1708. After Waller's death, William Derham received papers from Hooke's estate from Waller's brother-in-law Jonas Blackwell (? -1754). Hooke's diary was found in Harlow in 1891 and is now in the Guildhall Library in London.

During a routine appraisal of a country house in Hampshire in January 2006, papers were discovered which soon turned out to be lost papers from Robert Hooke's possession. The so-called "Hooke Folio" was to be auctioned on March 28th in New Bond Street in London. The President of the Royal Society, Martin Rees , publicly asked for donations so that the Royal Society could purchase the papers for their archives. Shortly before the start of the auction, over 150 donors, including a large donation from the Wellcome Trust , made it possible to purchase the “Hooke Folio” for 937,074 pounds. The “Hooke Folio” is accompanied by an index prepared by William Derham. It consists of two parts. The first hundred pages consist of notes from Hooke, which he excerpted from the reports of the Royal Society after the death of Henry Oldenburg in order to be able to prove his claims to priority. The remaining 400 or so pages are notes made by Hooke from January 1678 to November 1683 in his work as secretary during the weekly meetings of the Royal Society. The "Hooke Folio" is considered to be the most important manuscript find of the last 50 years that is connected to the early history of the Royal Society.

A drawing, Three Heads and Two Figure Studies , acquired by the Tate Britain art collection in 1996 and signed "R: Hook" was attributed to Robert Hooke in 2010 by Matthew C. Hunter.

Appreciation

The asteroid Hooke as well as the lunar crater Hooke and the Mars crater Hooke were named after Robert Hooke. Likewise the Hooke Point , a headland on the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula. Westminster School London named their science center, which opened in 1986, the Robert Hooke Science Center . The Hooke Medal of the British Society for Cell Biology reminiscent of Hooke's contributions to microscopy. The Hooke element represents the ideal elasticity in the rheological models .

Fonts

Books

During lifetime:

- An Attempt for the Explication of the Phaenomena, observable in an Experiment published by the Honorable Robert Boyle, Esq. London 1661.

- Micrographia: or, Some physiological descriptions of minute bodies made by magnifying glasses . London 1665, (online) .

- Published Cutler Lectures:

- An Attempt To Prove the Motion of the Earth from Observations . London 1674, (online) .

- Animadversions on the first part of the Machina coelestis… London 1674.

- A Description of Helioscopes and some other Instruments . London 1676, (online) .

- Lampas: or, Descriptions of some Mechanical Improvements of Lamps & Waterpoises. Together with some other physical and mechanical discoveries . London 1677.

- Lectures and collections. Cometa ... Microscopium ... London 1678.

- Lectures de potentia restitutiva, or, of Spring: explaining the power of springing bodies: to which are added some collections . London 1678.

- Lectiones Cutlerianae, or a Collection of Lectures: Physical, Mechanical, Geographical & Astronomical… John Martyn, London 1679, ( limited preview in Google book search). - The six Cutler lectures in one volume

Posthumously:

- Richard Waller (Ed.): The posthumous works of Robert Hooke . London 1705, (online) .

- William Derham (Ed.): Philosophical experiments and observations of the late eminent Dr. Robert Hooke… W. & J. Innys, London 1726 ( limited preview in Google book search).

In publications of the Royal Society (selection)

- A Spot in One of the Belts of Jupiter . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 1, number 1, March 6, 1665, p. 3, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1665.0005 .

- Mr. Hook's Answer to Monsieur Auzout's Considerations, in a Letter to the Publisher of These Transactions . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 1, number 4, June 5, 1665, pp. 64-69, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1665.0029 .

- The particulars. Of Those Observations of the Planet Mars, Formerly Intimated to Have Been Made at London in the Months of February and March A. 1665/6 . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 1, 1665, pp. 239-242, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1665.0101 .

- Some New Observations about the Planet Mars, Communicated Since the Printing of the Former Sheets . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 1, number 11, April 2, 1666, p. 198, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1665.0085 .

- A New Contrivance of Wheel-Barometer, Much More Easy to be Prepared, Than That, Which is Described in the Micrography; Imparted by the Author of That Book . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 1, number 13, June 4, 1666, pp. 218-219, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1665.0095 .

- Some Observations Lately Made at London Concerning the Planet Jupiter . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 1, number 14, July 2, 1666, pp. 245-247, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1665.0103 .

- Observations Made in Several Places, of the Late Eclipse of the Sun, Which Hapned on the 22 of June, 1666 . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 1, number 17, September 9, 1666, pp. 295-297, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1665.0111 .

- More Ways for the Same Purpose, Intimated by M. Hook . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 2, number 25, May 6, 1667, p. 459, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1666.0018 .

- An Account of an Experiment Made by Mr. Hook, of Preserving Animals Alive by Blowing through Their Lungs with Bellows . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 2, number 28, October 21, 1667, pp. 539-540, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1666.0043 .

- A Description of an Instrument for Dividing a Foot into Many Thousand Parts, and Thereby Measuring the Diameters of Planets to a Great Exactness, & c. as It Was Promised, Numb. 25 . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 2, number 29, November 11, 1667, pp. 541-556, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1666.0044 .

- A Contrivance to Make the Picture of Any Thing Appear on a Wall, Cub-Board, or within a Picture-Frame, & c. in the Midst of a Light Room in the Day-Time; Or in the Night-Time in Any Room That is Enlightned with a Considerable Number of Candles . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 3, number 38, August 17, 1668, pp. 741-743, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1668.0031 .

- Some Communications, Confirming the Present Appearance of the Ring about Saturn, by M. Hugens de Zulechem and Mr. Hook . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 5, number 65, November 14, 1670, p. 2093, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1670.0065 . - with Christiaan Huygens

- Observations Made by Mr. Hook, of Some Spots in the Sun, Return'd after they Had Passed Over the Upper Hemi Sphere of the Sun Which is Bid from Us; According as Was Predicted . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 6, number 77, November 20, 1671, pp. 2295-3001, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1671.0054 .

- An Account of What Bath Been Observed Here in London and Derby, by Mr. Hook, Mr. Flamstead, and Others, Concerning the Late Eclipse of the Moon, of Jan. 1. 1674/5 . Volume 9, number 111, February 22, 1675, pp. 237-238, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1674.0052 . - with John Flamsteed and Ismael Boulliau

- A way of helping short-sightedness . In: Philosophical Collections . Number 3, London 1681, p. 59 ff. ( Limited preview in the Google book search).

- Of the best form of horizontal sails for a mill, and of the inclined sails of ships . In: Philosophical Collections . Number 3, London 1681, p. 61 ff. ( Limited preview in the Google book search).

- Description of An Invention, Whereby the Divisions of the Barometer May be Enlarged in Any Given Proportions; Produced before the Royall Society By Mr. Robert Hook RS Soc. and profession. Geom. Gresham . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 16, 1686, pp. 241-244, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1686.0043 .

- An Account of Dr Robert Hook's Invention of the Marine Barometer, with Its Description and Uses, Published by Order of the R. Society, by E. Halley, RSS In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 22, number 269, 1700-1701, pp. 791-794, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1700.0074 . - with Edmond Halley

Buildings (selection)

- 1671–1676: The Monument to the Great Fire of London , Fish Street Hill, London

- 1672–1678: Royal College of Physicians , Warwick Lane, London

- 1675–1676: Bethlem Royal Hospital , London

- 1675–1679: Montague House, Bloomsbury, London

- 1679-1683: Ragley Hall, Warwickshire

- 1680: Will Church, Buckinghamshire

- 1690–1693: Almshouses Aske's Hospital, Hoxton, London

literature

Biographies

- Edward Andrade : Wilkins Lecture: Robert Hooke . In: Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences . Volume 137, Number 887, 1950, pp. 153-187, JSTOR: 82545 .

- Andrew Clark (Ed.): ' Brief Lives ' chiefly of contemporaries, set down by John Aubrey between the Years 1669 & 1696 . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1898, pp. 409-416, (on-line) .

- Margaret 'Espinasse: Robert Hooke . William Heinemann, London 1956.

- Stephen Inwood: The man who knew too much. The strange and inventive life of Robert Hooke (1635-1703) . Macmillan, London 2002, ISBN 0-333-78286-0 .

- Lisa Jardine: The curious life of Robert Hooke: the man who measured London . HarperCollins, 2003, ISBN 0-00-714944-1 .

- Robert D. Purrington: The First Professional Scientist: Robert Hooke and the Royal Society of London. Springer, Basel 2009, ISBN 978-3-0346-0036-1 .

Diaries

- Robert Theodore Gunther (Ed.): Later Diary . In: Early Science in Oxford . Volume 10, pp. 69-265, Oxford 1935. November 1, 1688 to March 9, 1690 and December 6, 1692 to August 8, 1693.

- Felicity Henderson: Unpublished Material from the Memorandum Book of Robert Hooke, Guildhall Library MS1758 . In: Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London . Volume 61, number 2, 2007, pp. 129-175, doi: 10.1098 / rsnr.2006.0173 - March 10 to July 31, 1672 and January 1681 to May 1683.

- Henry William Robinson, Walter Adams (Eds.): The diary of Robert Hooke, MA, MD, FRS, 1672-1680: transcribed from the original in the possession of the Corporation of the city of London . Taylor & Francis, London 1935 - March 1671/2 to May 1683.

bibliography

- Geoffrey Keynes: A Bibliography of Dr. Robert Hooke . Clarendon Press, 1960.

Reprints

- Robert T. Gunther: Early Science in Oxford .

- Volume 6: The life and work of Robert Hooke (Part 1) . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1930.

- Volume 7: The life and work of Robert Hooke (Part 2) . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1930.

- Volume 8: The Cutler lectures of Robert Hooke . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1931.

- Volume 10: The life and work of Robert Hooke. (Part 4) Tract on capillary attraction, 1661; Diary, 1688-1693 . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1935.

- Volume 13: The life and work of Robert Hooke (Part 5) Micrographia, 1665 . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1938.

On the reception of his work (selection)

- Jim Bennett, Michael Cooper, Michael Hunter, Lisa Jardine: London's Leonardo: the life and work of Robert Hooke . Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-19-852579-6 .

- Allan Chapman : England's Leonardo: Robert Hooke and the seventeenth-century scientific revolution . Institute of Physics, Bristol 2005, ISBN 0-7503-0987-3 .

- Michael Cooper: 'A more beautiful city.' Robert Hooke and the rebuilding of London after the Great Fire . Sutton Publishing, Stroud 2003, ISBN 0-7509-2959-6 .

- Michael Cooper, Michael Cyril William Hunter (Eds.): Robert Hooke: Tercentennial studies . Ashgate Publishing Ltd., 2006, ISBN 0-7546-5365-X .

- Ellen T. Drake: Restless genius: Robert Hooke and his earthly thoughts . Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-19-506695-2 .

- Ofer Gal: Meanest foundations and nobler superstructures: Hooke, Newton and the compounding of the celestial motions of the planetts . Springer, Dortrecht 2002, ISBN 1-4020-0732-9 .

- Michael Hunter, Simon Schaffer: (Ed.): Robert Hooke: New Studies . Boydell Press, Woodbridge 1989, ISBN 0-85115-523-5 .

- Paul Welberry Kent, Allan Chapman (Eds.): Robert Hooke and the English renaissance . Gracewing Publishing, 2005, ISBN 0-85244-587-3 .

- Richard Nichols (Ed.): The diaries of Robert Hooke, the Leonardo of London, 1635-1703 . Book Guild, 1994, ISBN 0-86332-930-6 .

- Robert D. Purrington: The First Professional Scientist: Robert Hooke and the Royal Society of London . Birkhäuser Verlag AG, Basel / Boston / Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-0346-0036-1 .

- Leona Rostenberg : The library of Robert Hooke: the scientific book trade of Restoration England . Modoc Press, Santa Monica 1989, ISBN 0-929246-01-2 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ All dates are based on the Julian calendar used in England at that time .

- ^ P. Breeze: The ancestry of Robert Hooke: John Hooke of Wroxhall . In: Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London . Volume 57, number 3, 2003, pp. 269-271, doi: 10.1098 / rsnr.2003.0213 .

- ↑ Andrew Clark (Ed.): 'Brief Lives' chiefly of contemporaries, set down by John Aubrey between the Years 1669 & 1696 . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1898, p. 409 ( online ).

- ^ Richard Waller (Ed.): The posthumous works of Robert Hooke . London 1705, p. II ( online ).

- ^ Hideto Nakajima: Robert Hooke's Family and His Youth: Some New Evidence from the Will of the Rev. John Hooke . In: Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London . Volume 48, Number 1, 1994, pp. 11-16, doi: 10.1098 / rsnr.1994.0002 .

- ^ Lisa Jardine: The curious life of Robert Hooke: the man who measured London . 2003, pp. 54-55.

- ↑ a b Richard Waller (ed.): The posthumous works of Robert Hooke . 1705, p. III ( online ).

- ↑ a b Andrew Clark (Ed.): 'Brief Lives' chiefly of contemporaries, set down by John Aubrey between the Years 1669 & 1696 . 1898, p. 410 ( online ).

- ^ Richard Waller (Ed.): The posthumous works of Robert Hooke . 1705, p. IV ( online ).

- ^ A b Mordechai Feingold: Robert Hooke: Gentleman of science . In: Michael Cooper, Michael Cyril William Hunter (Eds.): Robert Hooke: Tercentennial studies . 2006, pp. 203-218.

- ^ Edward Smith: Hooke and Westminster . In: Michael Cooper, Michael Cyril William Hunter (Eds.): Robert Hooke: Tercentennial studies . 2006, pp. 219-232.

- ↑ Paul Welberry Kent: Hooke's early life at Oxford . In: Robert Hooke and the English renaissance. Pp. 39-64.

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 1, p. 21 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 1, p. 124 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 1, p. 250 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 1, p. 442 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 1, p. 453 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 3, p. 344 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 1, p. 215 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 1, p. 442, June 22, 1664 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 1, p. 490, November 23, 1664 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ Penelope Gouk: The Harmonic Roots of Newton's Science . In: J. Fauvel, R. Flood, M. Shortland, R. Wilson (Eds.). Newton's Work: The Foundation of Modern Science. Birkhäuser Basel / Boston / Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-7643-2890-8 , pp. 153–155.

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 1, p. 465, September 7, 1664 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ Micrographia , observation 59: Of multitudes of small stars discoverable by the telescope .

- ^ A Spot in One of the Belts of Jupiter . 1665, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1665.0005 .

- ↑ Some Observations Concerning Jupiter. Of the Shadow of One of His Satellites Seen, by a Telescope Passing Over the Body of Jupiter . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 1, number 8, January 8, 1666, pp. 143-145, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1665.0067 .

- ^ Robert Hooke: Some New Observations about the Planet Mars, Communicated Since the Printing of the Former Sheets . April 2, 1666.

- ^ Observations Made in Italy, Confirming the Former, and Withall Fixing the Period of the Revolution of Mars . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 1, number 14, July 2, 1666, pp. 242–245, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1665.0102 .

- ^ Richard A. Proctor: A New Determination of the Diurnal Rotation of the Planet Mars . In: Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society . Volume 27, 1687, pp. 309-312; (online) .

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 2, London 1756, p. 98, June 20, 1666 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 2, London 1756, p. 315, October 22, 1668 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 2, London 1756, p. 394, July 15, 1669 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ The further parallax search from Hooke to Bradley . In: Harald Siebert: The great cosmological controversy: attempts at reconstruction using the Itinerarium exstaticum by Athanasius Kircher SJ (1602–1680) . Franz Steiner Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-515-08731-1 , pp. 276-294.

- ^ The Archimedean Engine . In: Alan W. Hirshfeld: Parallax: The Race to Measure the Cosmos . New York 2001, ISBN 0-7167-3711-6 , pp. 135-150.

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 1, p. 300 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 1, p. 311 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ A Method of Making a History of the Weather . In: Thomas Sprat: The history of the Royal Society of London, for the improving of natural knowledge . J. Martyn, London 1667, pp. 173-179 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ Louise Diehl Patterson: The Royal Society's Standard Thermometer, 1663-1709 . In: Isis . Volume 44, number 1/2, 1953, pp. 51-64, JSTOR: 227641 .

- ↑ Maurice Crewe: The fathers of scientific meteorology - Boyle, Wren, Hooke and Halley: Part 1 . In: Weather . Volume 58, Number 3, 2003, pp. 103-107, doi: 10.1256 / wea.95.02A .

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 3, p. 487 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ Maurice Crewe: The fathers of scientific meteorology - Boyle, Wren, Hooke and Halley: Part 2 . In: Weather . Volume 58, Number 4, 2003, pp. 135-139, doi: 10.1256 / wea.95.02B .

- ↑ Ellen T. Drake: The geological observations of Robert Hooke (1635-1703) on the Isle of Wigth . In: PN Wyse Jackson (Ed.): Four Centuries of Geological Travel: The Search for Knowledge on Foot, Bicycle, Sledge and Camel . Special Publications 287, Geological Society, London 2007, pp. 19-30, doi: 10.1144 / SP287.3 .

- ^ Rhoda Rappaport: Hooke on earthquakes: lectures, strategy and audience . In: The British Journal for the History of Science . Volume 19, 1986, pp. 129-146, doi: 10.1017 / S0007087400022937 .

- ^ AP Rossiter: The First English Geologist: Robert Hooke (1635-1703) . In: Durham University Journal Volume 27, 1935, pp. 172-181.

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 2, London 1756, p. 155 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ A b Michael AR Cooper: Robert Hooke's work as Surveyor for the City of London in the Aftermath of the Great Fire. Part One: Robert Hooke's first surveys for the City of London . In: Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London . Volume 51, number 2, 1997, pp. 161-174, doi: 10.1098 / rsnr.1997.0014 .

- ^ Matthew F. Walker: The Limits of Collaboration: Robert Hooke, Christopher Wren and the Designing of the Monument to the Great Fire of London . In: Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London . 2011, doi: 10.1098 / rsnr.2010.0092 .

- ↑ Christine Stevenson: Robert Hooke's Bethlem . In: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians . Volume 55, Number 3, 1996, pp. 254-275, JSTOR 991148 .

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 3, p. 1, January 11, 1672 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 3, p. 9, February 8, 1672 ( full text in Google book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 3, pp. 11–15, February 15, 1672 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ Of the colors observable in muscovy glass, and other thin bodies .

- ^ Westfall Richard: Isaac Newton. A biography . Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg / Berlin / Oxford 1996, ISBN 3-8274-0040-6 , p. 124.

- ↑ A Letter of Mr. Isaac Newton, Professor of the Mathematicks in the University of Cambridge; Containing His New Theory about Light and Colors: Sent by the Author to the Publisher from Cambridge, Feb. 6, 1671/72; In Order to be Communicated to the R. Society . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 6, number 80, February 19, 1672, pp. 3075-3087, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1671.0072 .

- ^ Westfall Richard: Isaac Newton. A biography . Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg / Berlin / Oxford 1996, ISBN 3-8274-0040-6 , pp. 127–129.

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 3, pp. 247-260, December 9, 1675 ( full text in Google book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 3, pp. 262-269, December 16, 1675 ( full text in Google book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 3, pp. 194–195, March 18, 1675 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 3, pp. 278-279, January 20, 1676 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ Westfall Richard: Isaac Newton. A biography . Spectrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg / Berlin / Oxford 1996, ISBN 3-8274-0040-6 , p. 142.

- ^ Westfall Richard: Isaac Newton. A biography . Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg / Berlin / Oxford 1996, ISBN 3-8274-0040-6 , p. 143.

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 3, p. 190 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ An Extract of the French Journal des Scavans, concerning a New Invention of Monsieur Christian Hugens de Zulichem, of Very exact and portative Watches . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 10, number 112, 1675, pp. 272-273, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1675.0005 .

- ^ A Declaration of the Council of the Royal Society, passed Novemb. 2o. 1676; relating to some Passages in a late Book of Mr. Hooke entltuled Lampas, & c. In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 11, number 129, November 20, 1676, pp. 749-750, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1676.0043 .

- ^ Rob Iliffe: "In the Warehouse": privacy, property and priority in the early Royal Society . In: History of Science . Volume 30, 1992, pp. 29-68; bibcode : 1992HisSc..30 ... 29I

- ^ Lisa Jardine: The curious life of Robert Hooke: the man who measured London . 2003, pp. 197-211.

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 2, pp. 69-72, March 21, 1666 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ A Statement of Planetary Movements as a Mechanical Problem . In: Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 2, pp. 90-92 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ Michael Nauen Berg: Robert Hooke's Seminal Contribution to Orbital Dynamics . In: Physics in Perspective . Volume 7, Number 1, 2005, pp. 4-34, doi: 10.1007 / s00016-004-0226-y .

- ^ Correspondence between Hooke and Newton and memoranda relating . In: WW Rouse Ball: An Essay on Newton's “Principia” . Macmillan, London 1893, pp. 139-153.

- ^ Jean Pelseneer: Une lettre inédite de Newton . In: Isis , Volume 12, Number 2, 1929, pp. 237-254, JSTOR: 224786 .

- ↑ Alexandre Koyré: An Unpublished Letter of Robert Hooke to Isaac Newton . In: Isis . Volume 43, Number 4, 1952, pp. 312-337, JSTOR: 227384

- ^ Robert Hooke to Isaac Newton, January 6, 1680, (online) : “ But my supposition is that the attraction is always in a duplicate proportion to the distance from the Center Reciprocall […] ”.

- ^ Edmond Halley to Isaac Newton, May 22, 1686, (online) .

- ^ Westfall Richard: Isaac Newton. A biography . Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg 1996, ISBN 3-8274-0040-6 , pp. 226-232.

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 3, p. 120 ( full text in the Google book search)

- ↑ Annus Climactericus. Gedani 1685. in folio. Wherein (amongst other things) he vindicates the justness of his Celestial Observations, against the exceptions by some made to the accuracy of them by Johannis Hevelii . In: Philosophical Transactions . Volume 15, number 175, 1685, pp. 1162-1183, doi: 10.1098 / rstl.1685.0063 .

- ^ Joseph Frederick Scott: The mathematical work of John Wallis, DD, FRS, (1616-1703) . Taylor and Francis, 1938, pp. 127-129.

- ^ Lisa Jardine: The curious life of Robert Hooke: the man who measured London . 2003, pp. 261-271.

- ^ Robert Hooke: A Description of Helioscopes and some other Instruments . London 1676, p. 31, (online) .

- ↑ Robert Hooke: Lectures de potentia restitutiva, or, of Spring: explaining the power of springing bodies: to which are added some collections . London 1678, p. 1 ( online ).

- ^ Albert E. Moyer: Robert Hooke's Ambiguous Presentation of "Hooke's Law" . In: Isis . Volume 68, Number 2, 1977, pp. 266-275, JSTOR: 230074 .

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 4, p. 96, July 27, 1681 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ Thomas Birch: The history of the Royal Society of London for improving of natural knowledge . Volume 4, p. 299, May 21, 1684 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ AR Hall: Two Unpublished Lectures of Robert Hooke . In: Isis . Volume 42, Number 3, 1951, pp. 219-230, JSTOR: 226559 .

- ^ Richard S. Nichols: Robert Hooke and the Royal Society . Book Guild, 1999, ISBN 1-85776-465-X , p. 18.

- ^ Anthony Wood: Athenae Oxonienses . 2nd Edition. Oxford 1721, pp. 1039-1040.

- ↑ Michael Hunter: Robert Hooke Revivified . In: Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London . Volume 58, number 1, 2004, pp. 89-91, doi: 10.1098 / rsnr.2003.0227 .

- ^ Robert Hooke Commemoration 2003 (accessed March 5, 2011).

- ↑ Conference program (accessed on March 5, 2011)

- ^ Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach: Strange journeys through Lower Saxony, Holland and Engelland . Volume 2, Ulm 1753, p. 551 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ John Gribbin : The Fellowship: The Story of the Royal Society and a Scientific Revolution . Penguin Group 2006, ISBN 0-14-101570-5 , p. 268.

- ^ [Anonymous]: Science: Old-Fashioned . In: Time . Volume 34, number 1, July 3, 1939, p. 39, text , image .

- ↑ MF Ashley Montagu: A Spurious Portrait of Robert Hooke (1635-1703) . In: Isis . Volume 33, Number 1, 1941, pp. 15-17, JSTOR: 330647 .

- ^ Lisa Jardine: The curious life of Robert Hooke: the man who measured London . 2003, pp. 15-19.

- ^ William B. Jensen: A Previously Unrecognized Portrait of Joan Baptista Van Helmont (1579-1644) . In: Ambix , Volume 51, Number 3, 2004, pp. 263-268; che.uc.edu (PDF)

- ↑ Is this the face of Robert Hooke? iwhistory.org.uk; accessed on March 25, 2018

- ↑ The Hooke portrait by Guy Heyden .

- ↑ Martin Kemp : Portrait: Updating Hooke . In: Nature . Volume 424, 2003, p. 255, doi: 10.1038 / 424255b .

- ^ Lisa Jardine: The curious life of Robert Hooke: the man who measured London . 2003, pp. 305-310.

- ↑ Frank Kelsall: Hooke's possessions at his Death: a hitherto Unknown Inventory . In: Michael Hunter, Simon Schaffer: (Ed.): Robert Hooke: New Studies . 1989, pp. 287-294.

- ↑ Bibliotheca Hookiana sive catalogus diversorum librorum: viz. Mathematic. Philosophic. ... insignium quos Doct. R. Hooke,… Quorum auctio habenda est Londini,… the 29th of April, 1703. Per Edoard Millington,… . [London 1703].

- ↑ Hooke's lost legacy: What really happened? . In: Lisa Jardine: The curious life of Robert Hooke: the man who measured London . 2003, p. 11.

- ^ Science's Missing Link: Robert Hooke and the Royal Society at Bonhams ( Memento December 8, 2006 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ The Hooke Folio ( memento June 19, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Entry at the Royal Society (accessed March 5, 2011)

- ^ Robyn Adams, Lisa Jardine: The return of the Hooke folio . In: Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London . Volume 60, number 3, 2006, pp. 235-239, doi: 10.1098 / rsnr.2006.0151 .

- ^ Three Heads and Two Figure Studies

- ^ Matthew C. Hunter: Hooke's figurations: a figural drawing attributed to Robert Hooke . In: Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London . Volume 64, number 3, 2010, pp. 251-260, doi: 10.1098 / rsnr.2009.0060 .

- ↑ Hooke Crater Dunes on Mars Odyssey THEMIS (accessed March 3, 2011).

- ↑ Our History ( July 9, 2014 memento on the Internet Archive ) on the Westminster School website (accessed March 3, 2011).

- ^ The Hooke Medal on the British Society for Cell Biology website (accessed March 3, 2011).

Web links

- www.roberthooke.org.uk

- Entry to Hooke; Robert (1635-1703); Natural Philosopher in the Archives of the Royal Society , London

- Michael Cooper: Now the dust has settled: A view of Robert Hooke post-2003 . Gresham lecture on November 5, 2008.

- The Hooke Folio Online

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hooke, Robert |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Hook, Robert |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English polymath |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 28, 1635 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Freshwater , Isle of Wight |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 14, 1703 |

| Place of death | London |