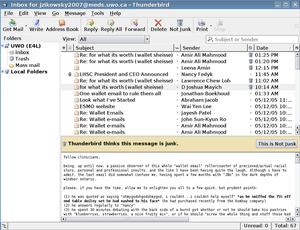

Email spam

E-mail spam or junk e-mail is a subset of spam that involves sending nearly identical messages to numerous recipients by e-mail. A common synonym for spam is unsolicited bulk e-mail (UBE). Some definitions of spam specifically include the aspects of email that is unsolicited and sent in bulk.[1][2][3][4][5] UCE refers specifically to Unsolicited Commercial E-mail.

Overview

From the beginning of the internet, sending of junk e-mail has been prohibited,[6] and enforced by ISP's Terms of Service (TOS) and by peer pressure. It is simply not possible for a thousand users to read a thousand messages a day, or today for a million users to read a million messages a day.[7] As the internet has grown, ISP's have no longer been able to police the sending of UBE and have turned to government for relief, which has failed to materialize, particularly in the US, which aborted tough state laws with a promiscuous federal law, the CAN-SPAM Act of 2003.

As the recipient directly bears the cost of delivery, storage, and processing, one could regard spam as the electronic equivalent of "postage-due" junk mail. Due to the low cost of sending unsolicited e-mail only an opt-in law will stop junk e-mail. "Today, much of the spam volume is sent by career criminals and malicious hackers who won't stop until they're all rounded up and put in jail."[8]

Spam is rarely sent by well-known companies, and is quickly regretted; spam from these sources is sometimes called mainsleaze[9]. A widely-known instance of spamming by a large corporation was Kraft Foods' marketing of its Gevalia coffee brand.[10] Advance fee fraud spam such as the Nigerian "419" scam may be sent by a single individual from a cyber cafe in a developing country. Organized "spam gangs" operating from Russia or eastern Europe share many features in common with other forms of organized crime, including turf battles and revenge killings.[11]

Spammers may engage in deliberate fraud to send out their messages. Spammers often use false names, addresses, phone numbers, and other contact information to set up "disposable" accounts at various Internet service providers. They also often use falsified or stolen credit card numbers to pay for these accounts. This allows them to move quickly from one account to the next as the host ISPs discover and shut down each one.

Spam is often used to collect personal information bought by other companies (phishing), allowing them to access your information typed in the "spam".

Senders may go to great lengths to conceal the origin of their messages. Large companies may hire another firm to send their messages so that complaints or blocking of email falls on a third party. Others engage in spoofing of e-mail addresses (much easier than IP address spoofing). The e-mail protocol (SMTP) has no authentication by default, so the spammer can pretend to relay a message apparently from any e-mail address. To prevent this, some ISPs and domains require the use of SMTP-AUTH, allowing positive identification of the specific account from which an e-mail originates. Senders cannot completely spoof e-mail delivery chains (the 'Received' header), since the receiving mailserver records the actual connection from the last mailserver's IP address. To counter this, some spammers forge additional delivery headers to make it appear as if the e-mail had previously traversed many legitimate servers.

Spammers frequently seek out and make use of vulnerable third-party systems such as open mail relays and open proxy servers. The SMTP system, used to send e-mail across the Internet, forwards mail from one server to another; mail servers that ISPs run commonly require some form of authentication that the user is a customer of that ISP. Open relays, however, do not properly check who is using the mail server and pass all mail to the destination address, making it quite a bit harder to track down spammers.

Increasingly, spammers use networks of virus-infected PCs (zombies) to send their spam. Zombie networks are also known as Botnets. In June 2006, an estimated 80% of e-mail spam were sent by zombie PCs, an increase of 30% from the prior year. An estimated 55 billion e-mail spam were sent each day in June 2006, an increase of 25 billion per day from June 2005.[12]

Spoofing can have serious consequences for legitimate e-mail users. Not only can their e-mail inboxes get clogged up with "undeliverable" e-mails in addition to volumes of spam, they can mistakenly be identified as a spammer. Not only may they receive irate e-mail from spam victims, but (if spam victims report the e-mail address owner to the ISP, for example) their ISP may terminate their service for spamming.

Statistics and estimates

The growth of e-mail spam

Spam is growing exponentially, with no signs of abating. The amount of spam users see in their mailboxes is just the tip of the iceberg, since spammers' lists often contain a large percentage of invalid addresses.

In absolute numbers

- 1978 - An e-mail spam is sent to 600 addresses.[13]

- 1994 - First large-scale spam sent to 6000 newsgroups, reaching millions of people.[14][15]

- 2005 - (June) 30 billion per day[12]

- 2006 - (June) 55 billion per day[12]

- 2006 - (December) 85 billion per day

- 2007 - (February) 90 billion per day

As a percentage of the total volume of e-mail

MAAWG estimates that 80-85% of incoming mail is "abusive email", as of the last quarter of 2005. The sample size for the MAAWG's study was over 100 million mailboxes.[16][17]

Highest amount of spam received

According to Steve Ballmer, Microsoft founder Bill Gates receives four million e-mails per year, most of them being spam.[18] (This was originally incorrectly reported as "per day".[19]) Ironically, most offered the world's wealthiest person opportunities for debt refinancing or get rich quick schemes.

At the same time Jef Poskanzer, owner of the domain name acme.com, was receiving over one million spam emails per day.[20]

Origin of spam

Origin or source of spam refers to the geographical location of the computer from which the spam is sent; it is not the country where the spammer resides, nor the country that hosts the spamvertised site. Due to the international nature of spam, often the spammer, the hijacked spam-sending computer, the spamvertised server, and the user target of the spam are all located in different countries.

In terms of volume of spam: According to Sophos, the major sources of spam in the first quarter of 2007 (January to March) were the United States (the origin of 19.8% of spam messages), followed by China (7.5%) and Poland (7.4%). When grouped by continents, spam comes mostly from Europe (35%), Asia (33%), and North America (23%).[21][22][23]

In terms of number of IP addresses: The Spamhaus Project (which measures spam sources in terms of number of IP addresses used for spamming, rather than volume of spam sent) ranks the top three as the United States, China, and Russia,[24] with South Korea placed at #6 behind Japan and Canada.

In terms of networks: As of 5 June 2007, the three networks hosting the most spammers are Verizon, AT&T, and VSNL International.[24] Verizon inherited many of these spam sources from its acquisition of MCI, specifically through the UUNet subsidiary of MCI, which Verizon subsequently renamed Verizon Business.

Spamvertised sites

Most spam contains a URL to a website. According to a Commtouch report in June 2004, "only five countries are hosting 99.68% of the global spammer websites", of which the foremost is China, hosting 73.58% of all web sites referenced within spam.[25]

Most common products advertised

According to information compiled by Spam-Filter-Review.com, E-mail spam for 2006 can be broken down as follows.[26]

| |

| Products | 25% |

| Financial | 20% |

| Adult | 19% |

| Scams | 9% |

| Health | 7% |

| Internet | 7% |

| Leisure | 6% |

| Spiritual | 4% |

| Other | 3% |

Pornography alone accounted for 2.5 billion daily emails sent in 2006, equating to 4.5 daily porn emails per person.[26]

Legality

Sending spam violates the Acceptable Use Policy (AUP) of almost all Internet Service Providers. Providers vary in their willingness or ability to enforce their AUP; some actively enforce their terms, some lack adequate personnel or technical skills for enforcement, while others may be reluctant to enforce restrictive terms against otherwise profitable customers.

In the United States spam is legally permissible according to the CAN-SPAM Act of 2003, provided it follows certain criteria: a truthful subject line; no false information in the technical headers or sender address; "conspicuous" display of the postal address of the sender; and other minor requirements. If the spam fails to comply with any of these requirements, then it is illegal. Aggravated or accelerated penalties apply if the spammer harvested the email addresses using methods described earlier.

Article 13 of the European Union Directive on Privacy and Electronic Communications (2002/58/EC) provides that the EU member states shall take appropriate measures to ensure that unsolicited communications for the purposes of direct marketing are not allowed either without the consent of the subscribers concerned or in respect of subscribers who do not wish to receive these communications, the choice between these options to be determined by national legislation.

In Australia, the relevant legislation is the Spam Act 2003 which covers some types of e-mail and phone spam, which took effect on 11 April 2004. Unlike the Can Spam Act (US)(opt-out), the Spam Act (AUS) provides that "Unsolicited commercial electronic messages must not be sent" (opt-in). Penalties are up to 10,000 penalty units (AUS $110 per penalty unit), approximately USD 900,000, or 2,000 penalty units for a person other than a body corporate.

Accessing privately owned computer resources without the owner's permission counts as illegal under computer crime statutes in most nations. Deliberate spreading of computer viruses is also illegal in the United States and elsewhere. Thus, some common behaviors of spammers are criminal regardless of the legality of spamming per se. Even before the advent of laws specifically banning or regulating spamming, spammers were successfully prosecuted under computer fraud and abuse laws for wrongfully using others' computers.

Legislative efforts to curb spam have been ineffective or counterproductive. For example, the CAN-SPAM Act of 2003 requires that each message include a means to "opt out" (i.e., decline future e-mail from the same source). It is widely believed that responding to opt-out requests is unwise, as this merely confirms to the spammer that they have reached an active e-mail account. If this is true, the CAN-SPAM Act's opt-out provisions are counterproductive in two ways: first, recipients who are aware of the potential risks of opting out will decline to do so; second, attempts to opt-out provide spammers with useful information on their targets. A 2002 study by the Center for Democracy and Technology found that about 16% of web sites tested with opt-out requests continued to spam.[27]

Anti-spam techniques

The US Department of Energy Computer Incident Advisory Committee (CIAC) has provided specific countermeasures against electronic mail spamming.[28]

Some popular methods for filtering and refusing spam include e-mail filtering based on the content of the e-mail, DNS-based blackhole lists (DNSBL), greylisting, spamtraps, enforcing technical requirements, checksumming systems to detect bulk email, and by putting some sort of cost on the sender via a Proof-of-work system or a micropayment. Each method has strengths and weaknesses and each is controversial due to its weaknesses.

Detecting spam based on the content of the e-mail, either by detecting keywords such as "viagra" or by statistical means, is very popular. Such methods can be very accurate when they are correctly tuned to the types of legitimate email that an individual gets, but they can also make mistakes such as detecting the keyword "cialis" in the word "specialist". The content also doesn't determine whether the email was either unsolicited or bulk, the two key features of spam. So, if a friend sends you a joke that mentions "viagra", content filters can easily mark it as being spam even though it is both solicited and not bulk.

The most popular DNSBLs are lists of IP addresses of known spammers, open relays, zombie spammers etc.

Spamtraps are often email addresses that were never valid or have been invalid for a long time that are used to collect spam. An effective spamtrap is not announced and is only found by dictionary attacks or by pulling addresses off hidden webpages. For a spamtrap to remain effective the address must never be given to anyone. Some black lists, such as spamcop, use spamtraps to catch spammers and blacklist them.

Enforcing technical requirements of the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) can be used to block mail coming from systems that are not compliant with the RFC standards. A lot of spammers use poorly written software or are unable to comply with the standards because they do not have legitimate control of the computer sending spam (zombie computer). So by setting restrictions on the mail transfer agent (MTA) a mail administrator can reduce spam significantly. In many situations, simply requiring a valid fully qualified domain name (FQDN) in the SMTP's EHLO (extended hello) statement is enough to block 25% of incoming spam. Some small organizations go so far as to remove their MX (Mail eXchange) record and arrange to have their A-record point to their SMTP server. RFC standards call for fall-back to a domain's A record when an MX lookup fails. While this method runs the risk of losing some legitimate e-mail from being received, some claim that it results in a 75% reduction in spam.

How bulk emailers operate

Gathering of addresses

In order to send spam, spammers need to obtain the e-mail addresses of the intended recipients. To this end, both spammers themselves and list merchants gather huge lists of potential e-mail addresses. Since spam is, by definition, unsolicited, this address harvesting is done without the consent (and sometimes against the expressed will) of the address owners. As a consequence, spammers' address lists are inaccurate. A single spam run may target tens of millions of possible addresses -- many of which are invalid, malformed, or undeliverable.

Spam differs from other forms of direct marketing in many ways, one of them being that it costs little more to send to a larger number of recipients than a smaller number. For this reason, there is little pressure upon spammers to limit the number of addresses targeted in a spam run, or to restrict it to persons likely to be interested. One consequence of this fact is that many people receive spam written in languages they cannot read — a good deal of spam sent to English-speaking recipients is in Chinese or Korean, for instance. Likewise, lists of addresses sold for use in spam frequently contain malformed addresses, duplicate addresses, and addresses of role accounts such as postmaster.[29]

Spammers may harvest e-mail addresses from a number of sources. A popular method uses e-mail addresses which their owners have published for other purposes. Usenet posts, especially those in archives such as Google Groups, frequently yield addresses. Simply searching the Web for pages with addresses — such as corporate staff directories — using spambots can yield thousands of addresses, most of them deliverable. Spammers have also subscribed to discussion mailing lists for the purpose of gathering the addresses of posters. The DNS and WHOIS systems require the publication of technical contact information for all Internet domains; spammers have illegally trawled these resources for email addresses. Many spammers utilize programs called web spiders to find email addresses on web pages. Usenet article message-IDs often look enough like email addresses that they are harvested as well.

Spammer viruses may include a function which scans the victimized computer's disk drives (and possibly its network interfaces) for email addresses. These scanners discover email addresses which have never been exposed on the Web or in Whois. A victimized computer located on a shared network segment may capture email addresses from traffic addressed to its network neighbors. The harvested addresses are then returned to the spammer through the bot-net created by the virus.

A recent, controversial tactic, called "e-pending", involves the appending of e-mail addresses to direct-marketing databases. Direct marketers normally obtain lists of prospects from sources such as magazine subscriptions and customer lists. By searching the Web and other resources for e-mail addresses corresponding to the names and street addresses in their records, direct marketers can send targeted spam e-mail. However, as with most spammer "targeting", this is imprecise; users have reported, for instance, receiving solicitations to mortgage their house at a specific street address — with the address being clearly a business address including mail stop and office number.

A more recent controversal tactic, should be called "triggered spam", so called "Postcard Services", e.g., are catching online consumers to have them send so called "Postcards" with more or less commercial content to redirect the recipients back to the sites of these "Postcard Services", mostly full of commercial advertisements and marketing data harvesting systems, which are received by the "Postcard" recipients in most cases unsolicitedly and without their consent, who are not subscribers of such a "Postcard Service".

Spammers sometimes use various means to confirm addresses as deliverable. For instance, including a Web bug in a spam message written in HTML may cause the recipient's mail client to transmit the recipient's address, or any other unique key, to the spammer's Web site.[30]

Likewise, spammers sometimes operate Web pages which purport to remove submitted addresses from spam lists. In several cases, these have been found to subscribe the entered addresses to receive more spam.[31]

When you fill out a form it is often sold to a spammer using a web service or http post to transfer the data. This is immediate and will drop the email in various spammer databases. The revenue made from the spammer is shared with the source. For instance if you ran an online mortgage, or signed up for a loan the owner of this site is likely to make a deal with the spammer to sell the address. These are considered the best emails by spammers because they are fresh and the user just signed up for a site that does well with spam anyway.

Sometimes, if the sent spam is "bounced" or sent back to the sender by various programs that eliminate spam, or if the recipient clicks on a unsubscribe link, that may cause that email address to be marked as "valid". Most of the time this is the case, although sometimes clicking will actually unsubscribe that email.

Delivering spam messages

Internet users and system administrators have deployed a vast array of techniques to block, filter, or otherwise banish spam from users' mailboxes. Almost all Internet service providers forbid the use of their services to send spam or to operate spam-support services. Both commercial firms and volunteers run subscriber services dedicated to blocking or filtering spam, such as AppRiver, GFI Software, Brightmail, SpamAssassin, MailRoute, Postini, Panda, MX Logic and the various DNSBLs.

Using Webmail services

A common practice of spammers is to create accounts on free webmail services, such as Hotmail, to send spam or to receive e-mailed responses from potential customers. Because of the amount of mail sent by spammers, they require several e-mail accounts, and use web bots to automate the creation of these accounts.

In an effort to cut down on this abuse, many of these services have adopted a system called the captcha: users attempting to create a new account are presented with a graphic of a word, which uses a strange font, on a difficult to read background. Humans are able to read these graphics, and are required to enter the word to complete the application for a new account, while computers are unable to get accurate readings of the words using standard OCR techniques. Blind users of captchas typically get an audio sample.

Spammers have, however, found a means of circumventing this measure. Reportedly, they have set up sites offering free pornography: to get access to the site, a user displays a graphic from one of these webmail sites, and must enter the word. Once the bot has successfully created the account, the user gains access to the pornographic material.

Using other people's computers

Early on, spammers discovered that if they sent large quantities of spam directly from their ISP accounts, recipients would complain and ISPs would shut their accounts down. Thus, one of the basic techniques of sending spam has become to send it from someone else's computer and network connection. By doing this, spammers protect themselves in several ways: they hide their tracks, get others' systems to do most of the work of delivering messages, and direct the efforts of investigators towards the other systems rather than the spammers themselves. The increasing broadband usage gave rise to a great number of computers that are online as long as they are turned on, and whose owners do not always take steps to protect them from malware. A botnet consisting of several hundred compromised machines can effortlessly churn out millions of messages per day. This also complicates the tracing of spammers.

Open relays

In the 1990s, the most common way spammers did this was to use open mail relays. An open relay is an MTA, or mail server, which is configured to pass along messages sent to it from any location, to any recipient. In the original SMTP mail architecture, this was the default behavior: a user could send mail to practically any mail server, which would pass it along towards the intended recipient's mail server.

The standard was written in an era before spamming when there were few hosts on the internet, and those on the internet abided by a certain level of conduct. While this cooperative, open approach was useful in ensuring that mail was delivered, it was vulnerable to abuse by spammers. Spammers could forward batches of spam through open relays, leaving the job of delivering the messages up to the relays.

In response, mail system administrators concerned about spam began to demand that other mail operators configure MTAs to cease being open relays. The first DNSBLs, such as MAPS RBL and the now-defunct ORBS, aimed chiefly at allowing mail sites to refuse mail from known open relays.

Open proxies

Within a few years, open relays became rare and spammers resorted to other tactics, most prominently the use of open proxies. A proxy is a network service for making indirect connections to other network services. The client connects to the proxy and instructs it to connect to a server. The server perceives an incoming connection from the proxy, not the original client. Proxies have many purposes, including Web-page caching, protection of privacy, filtering of Web content, and selectively bypassing firewalls.

An open proxy is one which will create connections for any client to any server, without authentication. Like open relays, open proxies were once relatively common, as many administrators did not see a need to restrict access to them.

A spammer can direct an open proxy to connect to a mail server, and send spam through it. The mail server logs a connection from the proxy -- not the spammer's own computer. This provides an even greater degree of concealment for the spammer than an open relay, since most relays log the client address in the headers of messages they pass. Open proxies have also been used to conceal the sources of attacks against other services besides mail, such as Web sites or IRC servers.

Besides relays and proxies, spammers have used other insecure services to send spam. One example is FormMail.pl, a CGI script to allow Web-site users to send e-mail feedback from an HTML form.[32] Several versions of this program, and others like it, allowed the user to redirect e-mail to arbitrary addresses. Spam sent through open FormMail scripts is frequently marked by the program's characteristic opening line: "Below is the result of your feedback form."

As spam from proxies and other "spammable" resources grew, DNSBL operators started listing their IP addresses, as well as open relays.

Spammer viruses

In 2003, spam investigators saw a radical change in the way spammers sent spam. Rather than searching the global network for exploitable services such as open relays and proxies, spammers began creating "services" of their own. By commissioning computer viruses designed to deploy proxies and other spam-sending tools, spammers could harness hundreds of thousands of end-user computers. The widespread change from Windows 9x to Windows XP for many home computers, which started in early 2002 and was well under way by 2003, greatly accelerated the use of home computers to act as remotely-controlled spam proxies. The original version of Windows XP as well as XP-SP1 had several major vulnerabilities that allowed the machines to be compromised over a network connection without requiring actions on the part of the user or owner. While Windows 2000 had similar vulnerabilities, that operating system was never widely used on home computers.

Most of the major Windows e-mail viruses of 2003, including the Sobig and Mimail virus families, functioned as spammer viruses: viruses designed expressly to make infected computers available as spamming tools.[33][34]

Besides sending spam, spammer viruses serve spammers in other ways. Beginning in July 2003, spammers started using some of these same viruses to perpetrate distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks upon DNSBLs and other anti-spam resources.[35] Although this was by no means the first time that illegal attacks have been used against anti-spam sites, it was perhaps the first wave of effective attacks.

In August of that year, engineering company Osirusoft ceased providing DNSBL mirrors of the SPEWS and other blocklists, after several days of unceasing attack from virus-infected hosts.[36] The very next month, DNSBL operator Monkeys.com succumbed to the attacks as well.[37] Other DNSBL operators, such as Spamhaus, have deployed global mirroring and other anti-DDoS methods to resist these attacks.

Obfuscating message content

Many spam-filtering techniques work by searching for patterns in the headers or bodies of messages. For instance, a user may decide that all e-mail they receive with the word "Viagra" in the subject line is spam, and instruct their mail program to automatically delete all such messages. To defeat such filters, the spammer may intentionally misspell commonly-filtered words or insert other characters, as in the following examples:

- V1agra

- Via'gra

- V I A G R A

- Vaigra

- \ /iagra

- Vi@graa

The principle of this method is to leave the word readable to humans (who can easily recognize the intended word for such misspellings), but not likely to be recognized by a literal computer program. This is only somewhat effective, because modern filter patterns have been designed to recognize blacklisted terms in the various iterations of misspelling. Other filters target the actual obfuscation methods; such as the non-standard use of punctuation or numerals into unusual places, for example: within in a word.

(Note: Using most common variations, it is possible to spell "Viagra" in over 1.3 * 1021 ways.[38])

HTML-based e-mail gives the spammer more tools to obfuscate text. Inserting HTML comments between letters can foil some filters, as can including text made invisible by setting the font color to white on a white background, or shrinking the font size to the smallest fine print.

Another common ploy involves presenting the text as an image, which is either sent along or loaded from a remote server. This can be foiled by not permitting an e-mail-program to load images.

As Bayesian filtering has become popular as a spam-filtering technique, spammers have started using methods to weaken it. To a rough approximation, Bayesian filters rely on word probabilities. If a message contains many words which are only used in spam, and few which are never used in spam, it is likely to be spam. To weaken Bayesian filters, some spammers, alongside the sales pitch, now include lines of irrelevant, random words, in a technique known as Bayesian poisoning. A variant on this tactic may be borrowed from the Usenet abuser known as "Hipcrime" -- to include passages from books taken from Project Gutenberg, or nonsense sentences generated with "dissociated press" algorithms. Randomly generated phrases can create spamoetry (spam poetry) or spam art.

After these nonsense subject lines were recognized as spam, the next trend in spam subjects started: Biblical passages. A program much like Mark V Shaney is fed Bible passages and chops them up into segments. The reasoning is that this text, very different from the writing style of today, will confuse both humans and spam filters.

Another method used to masquerade spam as legitimate messages is the use of autogenerated sender names in the From: field, ranging from realistic ones such as "Jackie F. Bird" to (either by mistake or intentionally) bizarre attention-grabbing names such as "Sloppiest U. Epiglottis" or "Attentively E. Behavioral". Return addresses are also routinely auto-generated, often using unsuspecting domain owners' legitimate domain names, leading some users to blame the innocent domain owners. Blocking lists use ip addresses rather than sender domain names, as these are more accurate. A mail purporting to be from example.com can be seen to be faked by looking for the originating ip address in the mails header, and Sender Policy Framework for example helps by stating that example.com will only send email from xx.xx.xx.xx ip.

Spam-support services

A number of other online activities and business practices are considered by anti-spam activists to be connected to spamming. These are sometimes termed spam-support services: business services, other than the actual sending of spam itself, which permit the spammer to continue operating. Spam-support services can include processing orders for goods advertised in spam, hosting Web sites or DNS records referenced in spam messages, or a number of specific services as follows:

Some Internet hosting firms advertise bulk-friendly or bulletproof hosting. This means that, unlike most ISPs, they will not terminate a customer for spamming.[39] These hosting firms operate as clients of larger ISPs, and many have eventually been taken offline by these larger ISPs as a result of complaints regarding spam activity. Thus, while a firm may advertise bulletproof hosting, it is ultimately unable to deliver without the connivance of its upstream ISP. However, some spammers have managed to get what is called a pink contract (see below) — a contract with the ISP that allows them to spam without being disconnected.

A few companies produce spamware, or software designed for spammers. Spamware varies widely, but may include the ability to import thousands of addresses, to generate random addresses, to insert fraudulent headers into messages, to use dozens or hundreds of mail servers simultaneously, and to make use of open relays. The sale of spamware is illegal in eight U.S. states.[40][35][41]

So-called millions CDs are commonly advertised in spam. These are CD-ROMs purportedly containing lists of e-mail addresses, for use in sending spam to these addresses. Such lists are also sold directly online, frequently with the false claim that the owners of the listed addresses have requested (or "opted in") to be included. Such lists often contain invalid addresses.[42] In recent years, these have fallen almost entirely out of use due to the low quality e-mail addresses available on them, and because some e-mail lists exceed 20GB in size. The amount you can fit on a CD is no longer substantial.

A number of DNSBLs, including the MAPS RBL, Spamhaus SBL, SORBS and SPEWS, target the providers of spam-support services as well as spammers. DNSBLs blacklist IPs or ranges of IPs to persuade ISPs to terminate services with known customers who are spammers or resell to spammers.

Related vocabulary

- Unsolicited bulk e-mail (UBE)

- A synonym for e-mail spam.

- Unsolicited commercial e-mail (UCE)

- Spam promoting a commercial service or product. This is the most common type of spam, but it excludes spam which are hoaxes (e.g. virus warnings), political advocacy, religious messages and chain letters sent by a person to many other people. The term UCE may be most common in the USA.[43]

- Pink contract

- A service contract offered by an ISP which offers bulk e-mail service to spamming clients, in violation of that ISP's publicly posted acceptable use policy.

- Spamvertising

- Advertising through the medium of spam.

- opt-in, confirmed opt-in, double opt-in, opt-out

- Whether the people on a mailing list are given the option to be put in, or taken out, of the list.

In the news

On November 4, 2004, Jeremy Jaynes, rated the 8th most prolific spammer in the world according to Spamhaus, was convicted of three felony charges of using servers in Virginia to send thousands of fraudulent e-mails. The court recommended a sentence of nine years' imprisonment, which was imposed in April 2005 although the start of the sentence is deferred pending appeals. Jaynes claimed to have an income of $750,000 a month from his spamming activities.

On December 31, 2004, British authorities arrested Christopher Pierson in Lincolnshire, UK and charged him with malicious communication and causing a public nuisance. On January 3, 2005, he pleaded guilty to sending hoax e-mails to relatives of people missing following the Asian tsunami disaster.

On July 25, 2005, Russian spammer Vardan Kushnir, who is believed to have spammed every single Russian internet user, was found dead in his Moscow apartment, having suffered numerous blunt-force blows to the head.[44]

On June 28, 2006, IronPort released a study which found 80% of spam emails originating from zombie computers. The report also found 55 billion daily spam emails in June 2006, a large increase from 35 billion daily spam emails in June 2005. The study used SenderData which represents 25% of global email traffic and data from over 100,000 ISP's, universities, and corporations.

On August 8, 2006, AOL announced the intention of digging up the garden of the parents of spammer Davis Wolfgang Hawke in search of buried gold and platinum.[45] AOL had been awarded a US$ 12.8 million judgment in May of 2005 against Hawke, who had gone into hiding. The permission for the search was granted by a judge after AOL proved that the spammer had bought large amounts of gold and platinum.[46]

On January 16, 2007, an Azusa, California man was convicted by a jury in United States District Court in Los Angeles in United States v. Goodin, U.S. District Court, Central District of California, 06-110, under the CAN-SPAM Act of 2003 (the first conviction under that Act).[47] He was sentenced to and began serving a 70 month sentence on June 11, 2007.[48]

On May 30, 2007, notorious spammer Robert Soloway was arrested after having being indicted by a federal grand jury on 35 charges including mail fraud, wire fraud, e-mail fraud, identity theft, and money laundering.[2] If convicted, he could face decades behind bars.[3]

Image spam

Image spam is an obfuscating method in which the text of the message is stored as a GIF or JPEG image and displayed in the email. This prevents text based spam filters from detecting and blocking spam messages. Image spam is currently used largely to advertise "pump and dump" stocks.[49]

Often, image spam contains non-nonsensical, computer-generated text which simply annoys the reader. However, new technology in some programs try to read the images by attempting to find text in these images. They are not very accurate, and sometimes filter out innocent images of products like a box that has words on it.

However, it now seems that the image no longer contains clear text in a static image format, but are embedded in an animated GIF, or lines are added to the background to mislead any image OCR tools, similar to CAPTCHA

Blank spam

Blank spam is spam lacking a payload advertisement. Often the message body is missing altogether, as well, as the subject line. Still, it fits the definition of spam because of its nature as bulk and unsolicited email.

Blank spam may be originated in different ways, either intentional or unintentionally:

- Blank spam can have been sent in a directory harvest attacks, a form of dictionary attack for gathering valid addresses from an email service provider. Since the goal in such an attack is to use the bounces to separate invalid addresses from the valid ones, the spammer may dispense with most elements of the header and the entire message body, and still accomplish his or her goals.

- Blank spam may also occur when a spammer forgets or otherwise fails to add the payload when he sets up the spam run.

- Often blank spam headers appear truncated, suggesting that computer glitches may have contributed to this problem -- from poorly-written spam software to shoddy relay servers, or any problems that may truncate header lines from the message body.

- Some spams may appear to be blank when in fact it is not. An example of this is the VBS.Davinia.B email worm which propagates through messages that have no subject line and appears blank, when in fact it uses html code to download other files.

See also

- Spamware

- Roger Ebert's Boulder Pledge

- Netiquette

- The news.admin.net-abuse.email newsgroup

- Spamhaus

- Chain e-mail

- Nigerian spam

- Make money fast, the infamous Dave Rhodes chain letter that jumped to e-mail.

- Disposable e-mail address

- Anti-spam techniques (e-mail)

- Integration of anti-spam techniques into MTAs

- Pump and dump stock fraud

- Spam (electronic)

- SpamCop

- Category:E-mail_spammers

- CAUCE

References

- ^ James John Farmer (27 December 2003). "3.4 Specific Types of Spam" (FAQ). An FAQ for news.admin.net-abuse.email; Part 3: Understanding NANAE. spamfaq.net. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ "You Might Be An Anti-Spam Kook If..." Rhyolite Software, LLC. 25 November 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ "On what type of email should I (not) use SpamCop?" (FAQ). SpamCop FAQ. IronPort Systems, Inc. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ Scott Hazen Mueller. "What is spam?". Information about spam. spam.abuse.net. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ "Spam Defined". Infinite Monkeys & Co. LLC. 22 December 2002. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ Gary Thuerk, who sent the first e-mail ad, in 1978, to 600 people, was reprimanded and told not to do it again.[1]

- ^ Why is spam bad?

- ^ CAUCE

- ^ "mainsleaze". Jargon File. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ^ "Trouble Brewing for Kraft and Gevalia Over Coffee Spam". PR Newswire. 2005-04-18. Retrieved 2007-06-02.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Brett Forrest (August 2006). "The Sleazy Life and Nasty Death of Russia's Spam King". Issue 14.08. Wired Magazine. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ a b c "Spammers Continue Innovation: IronPort Study Shows Image-based Spam, Hit & Run, and Increased Volumes Latest Threat to Your Inbox" (Press release). IronPort Systems, Inc. 28 June 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ Brad Templeton (Tue, 08 Mar 2005 08:30:08 GMT). "Reaction to the DEC Spam of 1978". Brad Templeton. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ J.S. Kelly (1 September 2002). "A brief history of spam". developerWorks. IBM. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ David Streitfeld (11 May 2003). "Opening Pandora's In-Box". Los Angeles Times (latimes.com). Retrieved 2007-01-06. free registration required to view article contents

- ^ "Email Metrics Program: The Network Operators' Perspective" (PDF). Report #1 — 4th Quarter 2005 Report. Messaging Anti-Abuse Working Group. March 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Email Metrics Program: The Network Operators' Perspective" (PDF). Report #2 — 1st Quarter 2006. Messaging Anti-Abuse Working Group. June 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Staff (18 November 2004). "Bill Gates 'most spammed person'". BBC News (bbc.co.uk). Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ Mike Wendland (2 December 2004). "Ballmer checks out my spam problem". ACME Laboratories republication of article appearing in Detroit Free Press. Retrieved 2007-01-06. the date provided is for the original article; the date of revision for the republication is 8 June 2005; verification that content of the republication is the same as the original article is pending

- ^ Jef Poskanzer (15 May 2006). "Mail Filtering". ACME Laboratories. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ "Sophos reveals 'Dirty Dozen' spam producing countries, August 2004" (Press release). Sophos Plc. 24 August 2004. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ "Sophos reveals 'dirty dozen' spam relaying countries" (Press release). Sophos Plc. 24 July 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ "Sophos research reveals dirty dozen spam-relaying nations" (Press release). Sophos Plc. 11 April 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ a b "Spamhaus Statistics : The Top 10". Spamhaus Blocklist (SBL) database. The Spamhaus Project Ltd. dynamic report. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Commtouch Reports Spam Trends For First Half of 2004" (Press release). Commtouch Software Ltd. 30 June 2004. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ a b Spam-Filter-Review Statistics

- ^ "Why Am I Getting All This Spam? Unsolicited Commercial E-mail Research Six Month Report". Center for Democracy and Technology. 2003. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) (Only 31 sites were sampled, and the testing was done before CAN-SPAM was enacted.) - ^ Shawn Hernan (25 November 1997). "I-005c: E-Mail Spamming countermeasures: Detection and prevention of E-Mail spamming". Computer Incident Advisory Capability Information Bulletins. United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rejo Zenger (25 December 2005). "what you get when you buy a spam cd". rejo.zenger.nl. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ Heather Harreld (5 December 2000). "Embedded HTML 'bugs' pose potential security risk". InfoWorld. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ "Spam Unsubscribe Services". The Spamhaus Project Ltd. 29 September 2005. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ Wright, Matt (2002-04-19). "Matt's Script Archive: FormMail". Retrieved 2007-06-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Staff (22 August 2003). "Spammer blamed for SoBig.F virus". CNN. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ Paul Roberts (11 July 2003). "New trojan peddles porn while you work". InfoWorld. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ a b "Spammers Release Virus to Attack" (Press release). The Spamhaus Project Ltd. 2 November 2003. Retrieved 2007-01-06. Cite error: The named reference "spaumhaus3" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Patrick Gray (27 August 2003). "Osirusoft 'closes doors' after crippling DDoS attacks". ZDNet Australia. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ "MONKEYS.COM: Now retired from spam fighting" (Blog) (Press release). DNSbl. 22 September 2003. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ "There are 600,426,974,379,824,381,952 ways to spell Viagra". cockeyed.com. 7 April 2004. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ Google Search: bulletproof spam hosting

- ^ Sapient Fridge (8 July 2005). "Spamware vendor list". spamsites.org. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ "Spamware - Email Address Harvesting Tools and Anonymous Bulk Emailing Software". MX Logic (abstract hosted by bitpipe.com). 1 October 2004. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) the link here is to an abstract of a white paper; registration with the authoring organization is required to obtain the full white paper - ^ Google Search: millions of email addresses

- ^ "Definitions of Words We Use". Coalition Against Unsolicited Bulk Email, Australia. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ "Russia's Biggest Spammer Brutally Murdered in Apartment". MOSNEWS.com. 25 July 2005. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ Colin Barker (16 August 2006). "AOL goes digging for spammer's gold". CNET Networks. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ Associated Press (15 August 2006). "AOL to dig for gold at home of spammer's folks". MSNBC. Retrieved 2007-01-06. the original link, http://www.businessweek.com/ap/tech/D8JH5OI80.htm, has expired

- ^ Edvard Pettersson (2006-01-16). "California Man Guilty of Defrauding AOL Subscribers, U.S. Says". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2007-01-22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ California Man Gets 6-Year Sentence For Phishing

- ^ Eric B. Parizo (26 July 2006). "Image spam paints a troubling picture". SearchSecurity.com. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (May 2007) |

- Anti-spam organizations and resources for e-mail users and administrators

- The anti-spam info & resource page of the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC)

- Yahoo's Anti-Spam Resource Center

- European SpamWiki Spamtrackers contains up-to-date information on spamgangs

- EU Spam Symposium's Archive

- AOL's postmaster page describing the Anti-Spam Technical Alliance (ASTA) Proposal

- The Coalition Against Unsolicited Bulk Email, Australia or CAUBE.AU

- The home page of the Anti Spam Research Group. ASRG is part of the IRTF, and affiliated with the IETF

- The European Union Directive on Privacy and Electronic Communications (2002/58/EC)

- Fight Spam on the Internet! - this site provides a plethora of advice for people who want to understand and fight spam.

- Pro-spam companies, organizations and resources for spam researchers

- Direct Marketing Association

- The Direct Email Advertisers Association (Charlotte NC USA) or DEAA and more information

- The Internet E-Mail Marketing Council (Stratham NH USA) or IEMMC

- EMarketersAmerica

- FutureNet Technologies

- Bulkers Club

- Major media sites, with current news on Spam e-mail

- Government reports and industry white papers

- Unsolicited Commercial E-mail Research Six Month Report by Center for Democracy & Technology

- Email Address Harvesting: How Spammers Reap What You Sow by the US FTC

- The Electronic Frontier Foundation's spam page which contains legislation, analysis and litigation histories

- An article about spam by the Scientific American : Stopping Spam

- Book published in 2004 about spammers and anti-spammers by Brian McWilliams : Spam Kings

- Historical Development of Spam Fighting in Relation to Threat of Computer-Aware Criminals, and Public Safety by Neil Schwartzman

- Spam works- An article analysing the success of spam as a way of touting stocks