Siege of Malakand

| Siege of Malakand | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-Afghan wars | |||||||

South Malakand Camp, August 1897 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| پشتون Pashtun tribes | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

William Hope Meiklejohn, Sir Bindon Blood | Fakir Saidullah[1] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,630 on July 26 1897[2] | 10,000[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

173 killed and wounded in the Malakand camps,[4][5] 33 killed and wounded at Chakdara,[6] 206 killed and wounded in total | At least 2000[7] | ||||||

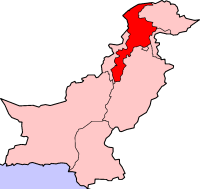

The Siege of Malakand was the 26 July - 2 August 1897 siege of the British garrison in the Malakand region of the North West Frontier Province[8] of modern day Pakistan. The British faced a force of Pashtun tribesmen whose tribal lands had been dissected by the Durand Line,[9] the 1,519 mile border between Afghanistan and Pakistan drawn up at the end of the Anglo-Afghan wars to help hold the Russian Empire's spread of influence towards British India.

The British forces were divided amongst a number of poorly defended positions, however the small garrison at the camp of Malakand South and the small fort at Chakdara were both able to hold out against the much larger Pashtun army until a relief column was sent to assist them. Accompanying this relief force was second lieutenant Winston S. Churchill, who later published his own account as The Story of the Malakand Field Force: An Episode of Frontier War.

Background

The rivalry between the British Empire and the Russian Empire, described as "The Great Game" by British intelligence officer of the British East India Company's Sixth Bengal Light Cavalry Arthur Conolly,[10] centered on Afghanistan during the late 19th century. From the British perspective, the Russian expansion threatened to destroy the so-called "jewel in the crown" of the British Empire, India. As the Tsar's troops began to subdue one Khanate after another the British feared that Afghanistan would become a staging post for a Russian invasion of India. It was with these thoughts in mind that, in 1838, the British launched the First Anglo-Afghan War and attempted to impose a puppet regime under Shuja Shah. The regime was short lived, however, and unsustainable without British military support. After the Russians sent an uninvited diplomatic mission to Kabul in 1878, tensions were again renewed and Britain demanded that the ruler of Afghanistan (Sher Ali) accept a British diplomatic mission. The mission was turned back and, in retaliation, a force of 40,000 men was sent across the border by the British, launching the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

After reaching a virtual stalemate with these two wars against the Afghans, the British imposed the Durand Line in 1893, which divided Afghanistan and what was then British India (now the North-West Frontier Province, Federally Administered Tribal Areas (F.A.T.A.) and Balochistan provinces of Pakistan). Named after Sir Mortimer Durand,[11] the foreign secretary of the British Indian government, it was agreed upon by the Emir of Afghanistan (Abdur Rahman Khan) and the representatives of British Empire, but deeply resented by the Afghans. Its intended purpose was to serve as a buffer zone to inhibit the spread of Russian influence down into British India.[11]

The Malakand Field Force

The British Malakand Field Force utilized the town of Nowshera[12] as a base of operations during the campaign. Nowshera was located south of the Kabul River " six hours by rail from Rawal Pindi".[13] Commanded by Colonel Schalch, the base served as a hospital during 1895, when the normal garrison of one British cavalry battalion, one Indian cavalry and one Indian infantry battalions were relocated to the front lines, 47 miles away at Malakand Pass in what was known as the Malakand South Camp,[13] itself 32 miles from Mardan.[14] Winston Churchill, who would accompany the relief force as a second lieutenant and war correspondent,[15] described the camp as "...a great cup, of which the rim is broken into numerous clefts and jagged points. At the bottom of this cup is the "crater" camp." Churchill goes on to state that the camp was viewed as purely temporary and was indefensible, due to its cramped conditions and the fact that it was dominated by nearby heights.[16] A nearby camp, North Malakand, was also established on the plains of Khar, intended to hold the large number of troops that were unable to fit into the main camp. Both of these positions were garrisoned for two years with little fear of attack.[16] Officers brought their families, and the camp held regular polo matches and shooting competitions.[17]

Outbreak of the battle

Towards 1897, news of unrest in the nearby Pashtun villages had reached the British garrisons in Malakand. Major Deane, the British political agent, noted the growing unrest within the Pashtun sepoys,[18] who stationed with the British, and his warnings were officially distributed to British officers on 23 July 1897; however, nothing more than at worst a minor skirmish was expected.[19][18] Rumors of a new religious leader, Saidullah the Sartor Fakir, also known as Mullah Mastun,[20][21], arriving to "sweep away" the British and inspire a "jihad"[22][23] were reportedly circulating the bazaars of Malakand during July. Saidullah became known by the British as "The Great Fakir", "Mad Fakir"[24] or the "Mad Mullah",[22] and by the Pashtuns as lewanai faqir or simply lewanai, which translates as "god-intoxicated".[21]

On July 26, while British officers were playing polo near camp Malakand North, indigenous spectators who were watching the match heard of an approaching Pashtun force and fled. Brigadier-General Meiklejohn, commander of the Malakand forces, was informed by Major Deane that "matters had assumed a very grave aspect" and that there were armed Pashtuns gathering nearby. Reinforcements from Mardan were requested, and Lieutenant P. Eliott-Lockhart departed at 1.30am.[25] At 09.45pm, a final telegram was received by the garrison stating that "the Fakir had passed Khar and was advancing on Malakand, that neither Levies nor people would act against him, and that the hills to the east of the camp were covered with Pathans."[26]

Malakand North and Malakand South

The night of July 26/27

South camp

The communication wire was cut shortly afterwards.[27] During the night of July 26, sometime after 10.00pm, a messenger arrived with word that the enemy had reached the village of Khar, three miles from Malakand.[27] A bugle call was immediately sounded within the camp. Lieutenant-Colonel McRae was to have been sent to Amandara Pass, four miles away, with the 45th Sikhs, two units from the 31st Punjaub Infantry, two Guns from No. 8 Mountain Battery and one Squadron from the 11th Bengal Lancers, with orders to hold the pass; however, the column of Pashtun forces had arrived at the South Malakand camp before this, surprising the British defenders,[28] and began to open fire on the garrison with muskets.[26] Lieutenant-Colonel McRae immediately sent a small number of men under Major Taylor down a road, from the "right flank" of the camp,[29] to ascertain the enemy's strength and location. McRae later followed with a small group of his own. Both parties aimed for a sharp turn in the oncoming road which, flanked by gorges, they hoped to hold the attacking force.[30] McRae, with about 20 men, opened fire on the Pashtun soldiers and began a fighting withdrawal 50 yards down the road before halting in an attempt to stop the attack. Major Taylor was mortally wounded and died quickly[31] and McRae suffered a neck wound. Reinforcements arriving under the command of Lieutenant Barff enabled the British to force back the Pashtun attack by 2.00am on the morning of July 27.[32][31] The official dispatches of General Meiklejohn noted that:

"There is no doubt that the gallant resistance made by this small body

in the gorge, against vastly superior numbers, till the arrival of the rest of the regiment, saved the camp from being rushed on that side, and I cannot speak too highly of the behaviour of Lieutenant-Colonel McRae

and Major Taylor on this occasion."[33]

Pashtun forces had successfully assaulted the camp in three other locations during this time, the 24th Punjaub Infantry's picket lines were quickly overrun, Pashtun sharpshooters occupied the nearby heights, causing continual casualties throughout the night, and the bazaar and surrounding buildings were occupied. Other units of the 24th, under Lieutenant Climo, retook the area and held it until 10.45pm that night, whereupon they were driven back and were under fire from sharpshooters.[33] The Pashtun forces broke through in a number of other locations, causing General Meiklejohn to get involved with the fighting. A Lieutenant Watling, commanding a group of British troops guarding the ammunitions stores at the Quarter Guard, was wounded and the ammunition stores were captured by the Pashtun forces. General Meiklejohn led a small group of sappers, members of the 24th and Captain Holland, Lieutenant Climo from the earlier charge and Lieutenant Manley to recapture the ammunition dump.[34] Captain Holland and the General were wounded, and the group severely depleted as it failed twice to retake the dump before being successful with a third attempt. Continuing crossfire from the enveloping Pashtun troops wounded a number of British officers, placing the command of the 24th with Climo. Towards 1.00am on the morning of July 27, Lieutenant Edmund William Costello rescued a wounded havildar while under fire and was later awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions.[35] As the night wore on, reinforcements were received from a nearby British hill fort, which had as yet been ignored by the Pashtun forces. At 4.15pm, the attacking forces withdrew with their dead and wounded. The British had lost a large number of officers wounded, and recorded 21 deaths among the sepoys.[36]

North camp

During the first night of the battle, Malakand North had not seen much action despite being in the more exposed position,[38] and had spent much of the night firing flares and moving artillery units around. Upon learning of this, General Meiklejohn ordered the northern camp to reconnoiter the valley around its position. Major Gibbs, the commander of this reconnaissance force, encountered large groups of tribesmen in the valley, and was eventually ordered to collect his forces and stores from the northern camp and evacuate them into the southern.

July 27

The last remaining forces from the now evacuated northern camp arrived in Malakand South at 8.30am on the 27th,[39] an event with coincided with the arrival of more Pashtun reinforcements. Back in Nowshera, the 11th Bengal Lancers were woken by telegrams describing the situation, and along with the 8th Dogras, the 35th Sikhs, No.1 and No.7 British Mountain Batteries, they set off to relieve the besieged garrison. Meanwhile at Malakand South, fresh Pashtun attacks were repulsed by elements of the 24th led by Lieutenant Climo, whose unit captured a Pashtun standard. At 7.30pm that evening the first of the British reinforcements arrived in the form of infantry from the Corps of Guides under Lieutenant Lockhart.[40] The 45th Sikhs, supported by 100 men from the Guides and two guns, remained astride the main road into the camp, while the 31st Punjuab Infantry held the centre, with the 24th under Climo at the north edge of Malakand South. Subadar Syed Ahmed Shah of the 31st held the area around the bazaar, though the market place itself was left unoccupied.[40]

At 8.00pm on the evening of the 27th, the Pashtuns attacked all the British positions at once. "Many thousands of rounds were discharged" and several charges were repulsed[41] Subadar Syed Ahmed Shah and his forces defended their position for several hours, however the Pashtuns were eventually successful in undermining the walls and killing the defenders. The surviving sepoys and their leader were awarded the Order of Merit. The 24th also repelled a number of charges, with VC recipient Costello being wounded in the arm. Climo led a counter-attack with two companies that was successful in pushing the attacking forces back by two miles despite constant harassment by musket fire, rifle fire and having large pieces of rubble thrown upon them. The British records for the night of July 27 record 12 killed among the sepoy ranks, as well as the wounding of Lieutenant Costello.[42]

July 28

The daylight hours of July 28 saw continuous harassing fire from the Pashtun sharpshooters established in the hills surrounding Malakand South, which wounded a number of British soldiers and one officer from the Guides, who were treated by the garrison surgeon, Lieutenant J.H. Hugo. Despite further attacks during the night of July 28/29, the British recorded only two killed from the sepoy ranks and the severe wounded of a Lieutenant Ford. Churchill records that Ford's bleeding artery was clamped shut by Hugo despite being under fire.[42]

July 29–July 31

The British garrison signalled the oncoming relief forces via heliograph at 8.00am on July 29 1897, communication having been re–established that morning. Their signal stated: "Heavy fighting all night. Expect more to–night. What ammunition are you bringing? When may we expect you?"[43] During the day, the Pashtuns prepared for another night attack while the British destroyed the bazaar and the regions previously defended, and lost, by Subadar Syed Ahmed Shah and the men of the 31st. Trees were also cut down to further improve fields of fire, however this activity did attract attention from the Pashtun sharpshooters.[44] Major Stuart Beatsen arrived at 4.00pm on the 29th with the 11th Bengal Lancers who had been summoned from Nowshera on July 27. The 35th Sikhs and 38th Dogras arrived at the mouth of the pass leading to Malakand South, however they halted there as a result of heat exhaustion that had already killed between 19[45] and 21[42] of their ranks. 2.00am in the morning of July 30 saw another Pashtun attack, during which the British Costello and the Pashtun Mullah were both wounded, and the British recorded one fatality among the sepoy contingent.[44]

The evening of July 30 saw another attack which was repulsed by a bayonet charge by the 45th Sikhs. On the morning of July 31 the remainder of the 38th Dogras and 35th Sikhs entered Malakand South under the command of Colonel Reid, bringing with them 243 mules carrying 291,600 rounds of ammunition.[46] Attacks by the Pashtun forces on Malakand South began to reduce and eventually ceased, the Mullahs instead turning their attention to Chakdara, a nearby British outpost. Churchill records a total of 3 British officers killed in action and 10 wounded, 7 sepoy officers wounded, and 153 non-commissioned officers killed and wounded during the siege of Malakand South.[44]

Relieving Chakdara

On July 28, when word of the attacks in Malakand were received, a division of "6800 bayonets, 700 lances or sabres, with 24 guns" was given to Major–General Sir Bindon Blood[18] with orders to hold "the Malakand, and the adjacent posts, and of operating against the neighbouring tribes as may be required."[47][48] Blood arrived at Nowshera on July 31 1897 to take command,[18] and on August 1 1897 he was informed that the Pashtun forces had turned their attention to the nearby British fort of Chakdara, a small, under garrisoned fort with few supplies that had itself been holding out with 200 men since the first attacks in Malakand began,[49] and had recently sent the signal "Help us" to the British forces.[50] Blood reached Malakand at noon on the same day.[47] While Blood and his relief force marched for Chakdara from the main camp at Nowshera, Brigadier–General Meiklejohn set out from Malakand South with the 45th, 24th and guns from No. 8 Battery. An advanced force of Guides cavalry under Captain Baldwin[51] met with an enemy force along the road, and were forced to retreat with two British officers and one sepoy officer wounded and 16 other ranks killed or wounded.[52][53]

Following on from this failed attempt, Blood arrived and appointed Colonel Reid commander of the forces at Malakand South, giving command of the rescue force to General Meiklejohn. The rescue column of 1000 infantry, two squadrons from the 11th Bengal Lancers, two of the Guides cavalry, 50 sappers, two cannons and a hospital detail,[47][54] rested on the night of August 1, despite a night attack by Pashtun forces. On the following day, the relief force advanced along the road to the abandoned Malakand North in order to avoid fire from the Pashtun sharpshooters who still occupied the heights around the Malakand South "cup".[55] The relief force assembled at 04.30am on August 2 with low morale, however with the use diversionary attacks the force was successful in breaking out of the Pashtun encirclement without loss, creating confusion amongst the Pashtun forces "like ants in a disturbed ant–hill" as observed Blood.[52] The 11th Bengal Lancers and the Gides cavalry went on to relieve the threatened fort at Chakdara, while the 45th Sikhs stormed nearby Pashtun positions. The British recorded 33 casualties from the action on August 2nd.[6]

Aftermath

The campaigns of the Malakand Field Force continued beyond the siege of Malakand South, North, and of the Chakdara fort. Immediately after the siege, two brigades of the British garrison were relocated to a new camp a few miles away to relieve the pressure in the overcrowded Malakand South. These received only light fire during August 5 1897, however on August 8 Saidullah rallied his surviving Pashtun forces and attacked the British garrison at Shabkadr fort near Peshawar. These attacks put the continued loyalty of friendly Pashtun levies guarding the British supply lines to Chitral at risk, thus endangering the supply convoys and their small escorts.[57] In response, on August 14 the British advanced further into Pashtun territory and engaged a force of "several thousand"[58] Pashtun tribesmen, with General Meiklejohn leading a flanking manoeuvre which split the Pashtun army in two, and forced it to pull back to Landakai.[59] The British forces continued to engage Pashtun tribesmen throughout the day, suffering two officers and 11 other ranks killed.[60]

The siege of Malakand was Winston Churchill's first experience of actual combat, which he later described in several newspaper columns for which he originally received £5 per column from The Daily Telegraph.[15], and that were eventually compiled into his first published book: The Story of the Malakand Field Force which began his career as a writer and politician.[61] Of the book's publication he remarked "[it] will certainly be the most noteworthy act of my life. Up to date (of course). By its reception I shall measure the chances of my possible success in the world".[15] Of the siege of Malakand, and of the entire campaign against the Pashtun tribes in northern Pakistan, Churchill remarked that they were a period of significant "transition".[62]

The War Office authorised the award of the clasp Malakand 1897 to the India Medal for those of the British and Indian armies who participated in this action.[63][64]

Notes

- ^ Edwards p. 263. also known as "Mullah Mastun" (Spain. 177, Easwaran p. 49) (Known by the Pashtun as: lewanai faqir, lewanai (Beattie p. 171), and by the British as "The Great Fakir", "Mad Fakir" (Hobday p. 13), or the "Mad Mullah", (Elliott-Lockhart p. 28)

- ^ Gore p. 403

- ^ A number of sources cite between 50,000 - 100,000 tribesmen as being present in the region during the siege (Wilkinson-Latham p. 20, Gore p. 405) while others give a figure of 10,000 for the actual siege (Easwaran p. 49)

- ^ Elliott-Lockhart p. 63

- ^ Churchill p. 48

- ^ a b Churchill p. 53

- ^ Elliott-Lockhart p. 83

- ^ Nevill p. 232

- ^ Lamb p. 93

- ^ Hopkirk p. 1

- ^ a b Lamb p. 94

- ^ Nevill p. 232

- ^ a b Churchill p. 11

- ^ Elliott-Lockhart p. 27

- ^ a b c "WINTER 1896-97 (Age 22) - "The University of My Life"". Sir Winston Churchill. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ a b Churchill p. 13

- ^ Churchill p. 14

- ^ a b c d Elliott-Lockhart p. 55

- ^ Churchill p. 27

- ^ Spain p. 177

- ^ a b Beattie p. 171

- ^ a b Elliott-Lockhart p. 28

- ^ Beattie p. 137

- ^ Hobday p. 13

- ^ Churchill p. 29

- ^ a b Churchill p. 31

- ^ a b Elliott-Lockhart p. 31

- ^ Elliott-Lockhart p. 30

- ^ Elliott-Lockhart p. 32

- ^ Churchill p. 34

- ^ a b Elliott-Lockhart p. 33

- ^ Churchill p. 35

- ^ a b Churchill p. 36

- ^ Churchill p. 39

- ^ Churchill p. 40

- ^ Churchill p. 41

- ^ A collection of photographs taken by Ben Tottenham, displayed on the BBC News site retrieved May 31 2007

- ^ Elliott-Lockhart p. 40

- ^ Churchill p. 44

- ^ a b Churchill p. 45

- ^ Churchill p. 46

- ^ a b c Churchill p. 47

- ^ Hobday p. 18

- ^ a b c Churchill p. 48

- ^ Elliott–Lockhart p. 53

- ^ Hobday p. 22

- ^ a b c Churchill p. 51

- ^ Raugh p. 222

- ^ Churchill p. 54

- ^ Hobday p. 32

- ^ Elliott–Lockhart p. 56

- ^ a b Churchill p. 52

- ^ Hobday p. 30

- ^ Elliott–Lockhart p. 59

- ^ Elliott–Lockhart p. 58

- ^ A pictures/6173431.stm collection of photographs taken by Ben Tottenham, displayed on the BBC News site retrieved May 31 2007

- ^ Elliott–Lockhart p. 80

- ^ Elliott–Lockhart p. 90

- ^ Elliott–Lockhart p. 93

- ^ Elliott–Lockhart p. 100

- ^ Jablonsky p. 300

- ^ Churchill p. 191

- ^ United Kingdom: India Medal 1895–1902 retrieved May 31 2007

- ^ Joslin p. 30

References

Printed sources:

- Beattie, Hugh Imperial Frontier: Tribe and State in Waziristan, 2002 ISBN 0700713093

- Churchill, Winston S. The Story Of The Malakand Field Force, 1897 (2004 publication: ISBN 1419184105)

- Edwards, David B. Heroes of the age: Moral Fault Lines on the Afghan Frontier, 1996 ISBN 0520200640

- Elliott–Lockhart, Percy C. and Dunmore, Edward M. Earl of Alexander A Frontier Campaign: A Narrative of the Operations of the Malakand and Buner Field Forces, 1897–1898, 1898

- Easwaran, Eknath Nonviolent Soldier of Islam: Badshah Khan, a Man to Match His Mountains, 1999 ISBN 1888314001

- Gore, Surgeon General at Nowshera, for The Dublin Journal of Medical Science, 1898

- Hobday, Edmund A. P. Sketches on Service During the Indian Frontier Campaigns of 1897, 1898

- Hopkirk, Peter The Great Game.: On Secret Service in High Asia, 2001 ISBN 0192802321

- Jablonsky, David Churchill and Hitler: Essays on the Political–Military Direction of Total War, 1994 ISBN 071464563X

- Joslin, Edward Charles The Standard Catalogue of British Orders, Decorations and Medals, 1972 ISBN 0900696486

- Lamb, Christina The Sewing Circles of Herat: A Personal Voyage Through Afghanistan, 2004 ISBN 0060505273

- Nevill, Hugh Lewis Campaigns on the North–west Frontier, 1912 (2005 publication: ISBN 1845741870)

- Raugh, Harold E. The Victorians at War, 1815–1914: An Encyclopedia of British Military History, 2004 ISBN 1576079252

- Spain, James William The Pathan Borderland, 1963 ASIN B0000CR0HH

- Wilkinson–Latham, Robert North–west Frontier 1837–1947, 1977 ISBN 0850452759

Websites:

- A collection of photographs taken by Ben Tottenham, displayed on the BBC News site retrieved May 31 2007

- "WINTER 1896–97 (Age 22) – "The University of My Life"". Sir Winston Churchill. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- United Kingdom: India Medal 1895–1902 retrieved May 31 2007