Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch (IPA: [ˈmʉŋk], December 12, 1863 – January 23, 1944) was a Norwegian Symbolist painter, printmaker, and an important forerunner of Expressionistic art.

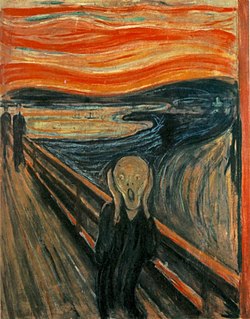

His best-known painting, The Scream (1893), is one of the pieces in a series titled The Frieze of Life, in which Munch explored the themes of life, love, fear, death, and melancholy. As with many of his works, he painted several versions of it.[1] Similar paintings include Despair and Anxiety

The Frieze of Life themes recur throughout Munch's work, in paintings such as The Sick Child (1886, portrait of his deceased sister Sophie), Love and Pain (1893-94) though more commonly known as "Vampire." Art critic Stanislaw Przybyszewski mistakenly interpreted the image as being vampiric in theme and content, and the description has since stuck, Ashes (1894), and The Bridge. The latter shows limp figures with featureless or hidden faces, over which loom the threatening shapes of heavy trees and brooding houses. Munch portrayed women either as frail, innocent sufferers (see Puberty and Love and Pain) or as the cause of great longing, jealousy and despair (see Separation, Jealousy and Ashes). Some say these paintings reflect the artist's sexual anxieties, though it could also be argued that they are a better representation of his turbulent relationship with love itself.

Biography

Youth

Edvard Munch was born in Ådalsbruk/Løten, Norway, and grew up in Kristiania (now Oslo). He was related to painter Jacob Munch (1776–1839) and historian Peter Andreas Munch (1810–1863). He lost his mother, Laura Cathrine Munch, née Bjølstad, to tuberculosis in 1868, and his older and favorite sister Sophie (Johanne Sophie b. 1862) to the same disease in 1877. Ultimately his father, Christian Munch, died young, as well, in 1889. Munch also had a brother, (Peter) Andreas (b. 1865) and two younger sisters (Laura Cathrine b. 1867, Inger Marie b. 1868). After their mother's death, the Munch siblings were raised by their father, who instilled in his children a deep-rooted fear by repeatedly telling them that if they sinned in any way, they would be doomed to hell without chance of pardon. One of Munch's younger sisters was diagnosed with mental illness at an early age. Munch himself was also often ill. Of the five siblings only Andreas married, but he died a few months after the wedding. He would later say, "Sickness, insanity and death were the angels that surrounded my cradle and they have followed me throughout my life."

Studies and influences

In 1879, Munch enrolled in a technical college to study engineering, but frequent illnesses interrupted his studies. In 1880, he left the college to become a painter. In 1881, he enrolled at the Royal School of Art and Design of Kristiania. His teachers were sculptor Julius Middelthun and naturalistic painter Christian Krohg.

While stylistically influenced by the postimpressionists, Munch's subject matter is symbolist in content, depicting a state of mind rather than an external reality. Munch maintained that the impressionist idiom did not suit his art. Interested in portraying not a random slice of reality, but situations brimming with emotional content and expressive energy, Munch carefully calculated his compositions to create a tense atmosphere.

Maturity

Munch's means of expression evolved throughout his life. In the 1880s, his idiom was both naturalistic, as seen in Portrait of Hans Jæger, and impressionistic, as in (Rue Lafayette). In 1892, Munch formulated his characteristic, and original, Synthetist aesthetic, as seen in Melancholy, in which colour is the symbol-laden element. Painted in 1893, The Scream is his most famous work.[2]

During the 1890s, Munch favoured a shallow pictorial space, a minimal backdrop for his frontal figures. Since poses were chosen to produce the most convincing images of states of mind and psychological conditions (Ashes), the figures impart a monumental, static quality. Munch's figures appear to play roles on a theatre stage (Death in the Sick-Room), whose pantomime of fixed postures signify various emotions; since each character embodies a single psychological dimension, as in The Scream, Munch's men and women appear more symbolic than realistic.

In 1892, the Union of Berlin Artists invited Munch to exhibit at its November exhibition. His paintings evoked bitter controversy, and after one week the exhibition closed. In Berlin, Munch involved himself in an international circle of writers, artists and critics, including the Swedish dramatist August Strindberg.

While in Berlin at the turn of the century, Munch experimented with a variety of new media (photography, lithography, and woodcuts), in many instances re-working his older imagery.

One of his great supporters in Berlin was Walter Rathenau, later the German foreign minister, who greatly contributed to his success.

In the autumn of 1908, Munch's anxiety became acute and he entered the clinic of Dr. Daniel Jacobson. The therapy (including electric shock therapy) Munch received in hospital changed his personality, and after returning to Norway in 1909 he showed more interest in nature subjects, and his work became more colourful and less pessimistic.

Later life

In the 1930s and 1940s, the National Socialists labeled his work "degenerate art", and removed his work from German museums. This deeply hurt Munch, who had come to feel Germany was his second homeland.

Munch built himself a studio and simple house at Ekly estate, at Skøyen, Oslo, and spent the last decades of his life there.[3] He died there on January 23, 1944, about a month after his 80th birthday.

- "From my rotting body, flowers shall grow and I am in them and that is eternity."

- —Edvard Munch

=Legacy

When Edvard died he left 1,008 paintings, 15,391 prints, 4,443 drawings and watercolors, and six sculptures to the city of Oslo which built the Munch Museum at Tøyen. The museum houses the broadest collection of his works. His works are also represented in major museums and galleries in Norway and abroad. After the Cultural Revolution in the People's Republic of China ended, Munch was the first Western artist to have his pictures exhibited at the National Gallery in Beijing.

Many contemporary artists, including Tracey Emin and Billy Childish, openly reference Munch in their work.

Munch appears on the Norwegian 1,000 Kroner note along with pictures inspired by his artwork. [1]

One version of The Scream was stolen in 1994, another in 2004. Both have since been recovered, but one version sustained damage during the theft which was too extensive to repair completely. In October 2006, the colour woodcut Two people. The lonely (To mennesker. De ensomme) set a new record for his prints when it was sold at an auction in Oslo for 8.1 million NOK (1.27 million USD). It also set a new record for the highest price paid in auction in Norway. [2]

Frieze of Life — A Poem about Life, Love and Death

In December 1893, Unter den Linden in Berlin held an exhibition of Munch's work, showing, among other pieces, six paintings entitled Study for a Series: Love. This began a cycle he later called the Frieze of Life — A Poem about Life, Love and Death. Frieze of Life motifs such as The Storm and Moonlight are steeped in atmosphere. Other motifs illuminate the nocturnal side of love, such as Rose and Amelie and Vampire. In Death in the Sickroom (1893), the subject is the death of his sister Sophie. The dramatic focus of the painting, portraying his entire family, is dispersed in a series of separate and disconnected figures of sorrow. In 1894, he enlarged the spectrum of motifs by adding Anxiety, Ashes, Madonna and Women in Three Stages.

Around the turn of the century, Munch worked to finish the Frieze. He painted a number of pictures, several of them in larger format and to some extent featuring the Art Nouveau aesthetics of the time. He made a wooden frame with carved reliefs for the large painting Metabolism (1898), initially called Adam and Eve. This work reveals Munch's preoccupation with the "fall of man" myth and his pessimistic philosophy of love. Motifs such as The Empty Cross and Golgotha (both c. 1900) reflect a metaphysical orientation, and also echo Munch's pietistic upbringing. The entire Frieze showed for the first time at the secessionist exhibition in Berlin in 1902.

List of major works

- 1892 - Evening on Karl Johan

- 1893 - The Scream

- 1894 - Ashes

- 1894-95 - Madonna

- 1895 - Puberty

- 1895 - Self-Portrait with Burning Cigarette

- 1895 - Death in the Sickroom

- 1899-1900 - The Dance of Life

- 1899-1900 - The Dead Mother

- 1940-42 - Self Portrait: Between Clock and Bed

See also

Notes

- ^ In a note in his diary, Munch described his inspiration for the image. “I was walking along a path with two friends — the sun was setting — suddenly the sky turned blood red. I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence — there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city — my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety. I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.” –Edward Munch (Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Scream)

- ^ Some art historians believe that the red sky in the background of The Scream reflects the unusually intense sunsets seen throughout the world following the 1883 eruption of the Indonesian volcano Krakatoa.

- ^ Chipp, H.B. Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics, page 114. University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-05256-0

References

- Fineman, Mia (Nov. 22, 2005). "Existential Superstar". Slate (magazine).

Further reading

- Sue Prideaux, Behind the Scream (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006) Winner of the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for Biography, 2006

- Reinhold Heller, Munch. His life and work (London: Murray, 1984).

- Gustav Schiefler, Verzeichnis des graphischen Werks Edvard Munchs bis 1906 (Berlin: Bruno Cassirer, 1907).

- Gustav Schiefler, Edvard Munch. Das graphische Werk 1906–1926 (Berlin: Euphorion, 1928).

- J. Gill Holland The Private Journals of Edvard Munch: We Are Flames Which Pour out of the Earth (University of Wisconsin Press 2005)

- Edward Dolnick The Rescue Artist: A True Story of Art, Thieves, and the Hunt for a Missing Masterpiece (HarperCollins, 2005) (Recounts the 1994 theft of The Scream from Norway's National Gallery in Oslo, and its eventual recovery.)

External links

- The Munch Museum

- The Dance of Life Site

- Edvard Munch Catalogue Raisonné

- Munch at Olga's Gallery -- large online collection of Munch's works (over 200 paintings)

- Munch at artcyclopedia

- Interpol's page about the stolen works of art

- Rothenberg A. Bipolar illness, creativity, and treatment. Psychiatr Q. 2001 Summer;72(2):131-47.

- "Appeals court boosts jail terms for Munch robbery". Aftenposten. April 23 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)