Fazlur Rahman Malik and Indiana Mammoth Internal Improvement Act: Difference between pages

hazara cat |

copy edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

The '''Mammoth Internal Improvement Act''' was a law passed by the [[Indiana General Assembly]] in 1836 that greatly expanded the state of [[Indiana]]'s internal improvement program. It added an additional $10 million ([[USD]]) to spending and funded several projects, including [[turnpikes]], [[canal]]s, and [[railroad]]s. The following year the state economy was adversly affected by the [[Panic of 1837]] and the overall project ended in a near total disaster for the state, which narrowly avoided [[bankrutpcy]] from the debt. By 1841, the the government could no longer make even the interest payment, and all the projects, except the largest canal, were handed over to the state's [[London]] creditors in exchange for a 50% reduction in debt. Again in 1846, the last project was handed over for another 50% in debt. Of the eight projects in the measure, none were completed by the state. Only two were finished by the creditors who took them over. The act is considered one of the greatest debacles in the history of the state. |

|||

'''Fazlur Rahman Malik''' ([[Urdu]]: '''فضل الرحمان ملک''') ([[September 21]], [[1919]] – [[July 26]], [[1988]]) was a well-known scholar of [[Islam]]; M. Yahya Birt of the Association of Islam Researchers described him as "probably the most learned of the major Muslim thinkers in the second-half of the twentieth century, in terms of both classical Islam and Western philosophical and theological discourse." |

|||

==Background== |

|||

Rahman was born in the [[Hazara, Pakistan|Hazara]] area of [[British India]] (now [[Pakistan]]). His father, [[Maulana Shihab al-Din]], was a well-known scholar of the time who had studied at [[Deoband]] and had achieved the rank of [[alim]], through his studies of Islamic law ([[fiqh]], [[hadith]], [[Qur'an]]ic [[tafsir]], logic, philosophy and other subjects). |

|||

When the state of Indiana was formed in 1816, it was still a virtual wilderness, and settlement was limited to the southern periphery where easy access to the [[Ohio River]] provided a convenient means to export produce. The only significant road in the region was the [[Buffalo Trace (road)|Buffalo Trace]], an old dirt bison trail that crossed the southern part of the state. After statehood several plans had been made to improve the transportation situation, like the creation of small local roads, the larger [[Michigan Road]], and a failed attempted by the [[Indiana Canal Company]] to build a canal around the [[Falls of the Ohio]]. The national economy entered a recession following the [[Panic of 1819]], and the states only two banks collapsed in the years that followed, ending the states improvement programs with having achieved little success. |

|||

Rahman studied [[Arabic language|Arabic]] at [[University of the Punjab|Punjab University]], and went on to [[Oxford University]] where he wrote a dissertation on [[Ibn Sina]]. Afterwards, he began a teaching career, first at [[Durham University]] where he taught [[Persian Empire|Persian]] and Islamic philosophy, and then at [[McGill University]] where he taught Islamic studies until 1961. |

|||

The 1820s were spent repairing the state's finances and by 1831 the state had began to restart the internal improvement projects using land grants from teh federal government.<ref>Shaw, p. 135</ref> The [[Wabash and Erie Canal]] was started with local funds, but was taken over by the state that year, who continued to expand it. To fund the project, and in response to the closure of the [[Second Bank of the United States]], the state established the [[Bank of Indiana]]. Bonds were issued through the bank to fund the early stages of the project, but it soon became apparent that it would take far more funds than could be obtained by bonds alone. |

|||

In that year, he returned to Pakistan to head up the Central Institute of Islamic Research which was set up by the Pakistani government in order to implement Islam into the daily dealings of the nation. However, due to the political situation in Pakistan, Rahman was hindered from making any progress in this endeavour, and he resigned from the post. He then returned to teaching, moving to the [[United States]] and teaching at [[UCLA]] as a visiting professor for a few years. He moved to the [[University of Chicago]] in 1969 and established himself there becoming the Harold H. Swift Distinguished Service Professor of Islamic Thought. At Chicago he was instrumental for building a strong [[Near East]]ern Studies program that continues to be among the best in the world. Rahman also became a proponent for a reform of the Islamic polity and was an advisor to the [[United States Department of State|State Department]]. He died in 1988. |

|||

==Passage of the law== |

|||

Since Rahman's death his writings have continued to be popular among scholars of Islam and the Near East. His contributions to the University of Chicago are still evident in its excellent programs in these areas. In his memory, the [[Center for Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Chicago]] named its common area after him, due to his many years of service the Center and the University of Chicago at large. |

|||

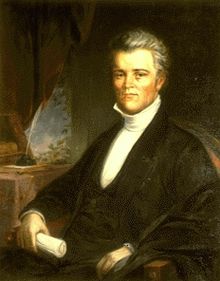

[[image:Noah Noble Portrait.jpg|thumb|right|Governor Noah Noble, primary backer of the law.]] |

|||

In 1836, legislation was created by the [[Indiana General Assembly]] to dramatically expand the scope of the internal improvements. Over $2 million had already been burrowed, and the new bill proposed borrowing another $10 million. Seeing the success of canals in the [[eastern United States]], it was believed that the projects would be very profitable for the state and that their revenue would quickly pay back the loans, and provide the funds to complete the projects. |

|||

== Publications == |

|||

*''Islam'', University of Chicago Press, 2nd edition, 1979. ISBN 0-226-70281-2 |

|||

*''Islam and Modernity: Transformation of an Intellectual Tradition'', University of Chicago Press, 1982. ISBN 0-226-70284-7 |

|||

*''Major Themes of the Qur'an'', Biblioteca Islamica, 1994. ISBN 0-88297-051-8 |

|||

*''Revival and Reform in Islam'' (ed. [[Ebrahim Moosa]]), Oneworld Publications, 1999. ISBN 1-85168-204-X |

|||

*''Islamic Methodology in History'', Central Institute of Islamic Research, 1965. |

|||

*''Health and Medicine in the Islamic Tradition'', Crossroad Pub Co, 1987. ISBN 0-8245-0797-5 (Hardcover), ISBN 1-871031-64-8 (Softcover). |

|||

*[http://www.globalwebpost.com/farooqm/study_res/i_econ_fin/frahman_riba.pdf Riba and Interest], ''Islamic Studies'' (Karachi) 3(1), Mar. 1964:1-43. |

|||

*[http://www.globalwebpost.com/farooqm/study_res/fazlur_rahman/f_rahman_shariah.doc Shariah], Chapter from ''Islam'' [Anchor Book, 1968], pp. 117-137. |

|||

For canals, the project called for the creation of a canal from [[Indianapolis]] to [[Evansville, Indiana|Evansville]], called the [[Indiana Central Canal]]. It was intended to connect the Wabash and Erie Canal to the [[Ohio River]]. Funding was included for another canal to connect Indianapolis to the [[Wabash River]] in [[Lafayette, Indiana|Lafayette]] known as the [[Whitewater Canal]]. Additional funding was granted to the Wabash and Erie Canal for expansion to [[Terre Haute, Indiana|Terre Haute]]. The canals received the majority of the funds from the bill, because it was believed that the canals could be constructed from local materials which would help boost the local economy.<ref>Shaw, p. 137</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*[[Contemporary Islamic philosophy]] |

|||

*[[Islamism]] |

|||

The bill also funded, but to a much lesser degree, a railroad connecting [[Madison, Indiana|Madison]] to Indianapolis, the paving of the [[Buffalo Trace (road)|Buffalo Trace]] and renaming it the Vincennes Trace, the pavement of the remainder of the Michigan Road. The money from the project was gathered by mortgaging nine million acres of state owned land through the Bank of Indiana to creditors in London, with the bank being the actual bond holder, but the state responsible for insuring the bank. |

|||

== References == |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Governor of Indiana|Governor]] [[Noah Noble]] was a major supporter of the bill and it passed by the overwhelmingly [[Whig]] controlled General Assembly, although it was opposed by several prominent legislators including [[Dennis Pennington]], [[James Whitcomb]], Calvin Flethcer and John Durmont. Pennington believed the canals were a waste of money and would soon be made obsolete by the railroads.<ref>Dunn, p. 408</ref> Whitcomb outright rejected the idea of spending such a large sum of money, saying it would be impossible to pay back.<ref>Woollen, p. 82</ref> |

|||

==External links== |

|||

*[http://hangingodes.wordpress.com/2006/11/10/revisiting-fazlur-rahmans-ordeal/ Revisiting Fazlur Rahman's Ordeal] |

|||

The bill created a Board of Improvement and a Board of Funds Commissioners to oversee the projects. Two thirds of the funds were spent on the canals, with the Central Canal getting the most money.<ref>Shaw, p. 138</ref> [[Jesse L. Williams]] was named cheif engineer.<ref>Shaw, p. 139</ref> |

|||

==Enactment== |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fazlur}} |

|||

[[Image:Wabash and Erie Canal (Delphi).png|thumb|right|A restored section of canal in [[Delphi, Indiana]].]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:1988 deaths]] |

|||

[[Category:Hazara_people]] |

|||

[[Category:Muslim philosophers]] |

|||

[[Category:Muslim scholars]] |

|||

[[Category:Muslim scholars of Islam]] |

|||

[[Category:Pakistani writers]] |

|||

[[Category:Pakistani scholars]] |

|||

[[Category:Pakistani people]] |

|||

[[Category:Academics of Durham University]] |

|||

[[Category:University of Chicago faculty]] |

|||

From the early onset it was noted that the project did not work together, but instead competed with each other for funds and land. This posed a problem for the government, because they did not provide enough funds to complete each of the projects, instead expecting them to start making money on their own.<ref>Shaw, p. 138</ref> Several small supplemental funding bills, adding approximately $2 million more dollars for use by the projects. The Wabash and Erie Canal was the most successful of the canal projects, and was profitable early on, but never to the extent expected. The Central Canal was major failure, with only a few miles of canal dug near Indianapolis before the project was out of money. The Whitewater Canal was p proceeding along well until it's earthen walls and feeder dams were the victims of [[muskrats]] who burrowed through the walls, causing hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages for which there was no money to repair. At the height of the operation, over ten thousand workers were employed on the canal projects.<ref>Shaw, p. 139</ref> |

|||

[[fa:فضل الرحمن]] |

|||

[[nl:Fazlur Rahman]] |

|||

The rail line from Madison to Indianapolis was built much more cheaply than the canals. It was however, considerably over budget due to an increased costs of having to build a grade out of the low lying [[Ohio Valley]] onto the Indiana table land, so the project could not be finished. The Vincennes Trace was paved from [[New Albany, Indiana|new Albany]] to [[Paoli, Indiana|Paoli]], with another 75 miles still requiring pavement. |

|||

The [[Panic of 1837]] left the state in dire straites financially. By 1839 there was no money left for the projects and all work was halted. Work only continued on the Wabash and Erie where workers were paid with stock in the canal, and not cash. 140 miles of canal had been built for $8 million, and $1.5 million on 70 miles of railroad and turnpike. The state was left with a $13 million dollar debt, and only a trickle of tax revenue. [[James Lanier]], president of the Bank of Indiana, was sent by Governor [[Samuel Bigger]] to negotiate with the state's [[London]] creditors in a hope to avoid total bankruptcy. He negotiated the transfer of all of the projects, except the Wabash and Erie, to the creditors in exchange for a 50% reduction in the debt to $6.5 million dollars.<ref>Shaw, p. 139</ref> |

|||

The Whigs suffered from the failure of the project and Democrat James Whitcomb, an opponent of the projects from the begining, was elected governor. He sent another representative to London and sold the Wabash and Erie for another 50% reduction in the debt to $3 million, ending the financial crisis. The result was a windfall for the Bank of Indiana, who ended with a 650% profit, but the state loosing millions. The state was, however, a 50% owner of the bank and recieving a $3.5 million dividend back from the bank which was put into the state's education fund.<ref>Dunn, p. 415</ref> |

|||

==Aftermath== |

|||

[[Image:Jameswhitcombindiana.jpg|thumb|right| Governor [[James Whitcomb]], opponent of the law, and man who sold off the last of the public works.]] |

|||

The creditors had taken the public works expecting that they could be quickly completed and become profitable. The Vincennes Trace was renamed the Paoli Pike, and operated for several years as a toll road. The Central Canal and Whitewater Canal were abandoned as a total loss, the expense to finish them was considered to be to great for their possible profitability. The Wabash and Erie Canal continued to operated for several decades, but quickly went into decline in the next decade as it was made obsolete by the railroads. The line from Madison to Indianapolis was also abandoned by the creditors and sold to entrepreneurs who were able to raise funds to complete the line. It was instantly profitable and went on to expand and connect to several other cities. |

|||

Although the government lost millions, there were significant benefits for the areas of the state where the projects succeeded. On average, land value in the state rose 400%, and the cost of shipping goods for farmers was drastically decreased, and increasing the profit on their goods. The investors in the Bank of Indiana also made substantial profits, and the investments served as the start of a modern economy for the state.<ref>Dunn, p. 418</ref> The act is often considered the greatest legislative debacle in the history of the state. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{portal|Indiana|Indiana state flag detail.jpg||150px|break=no|left=no}} |

|||

*[[History of Indiana]] |

|||

*[[Wabash and Erie Canal]] |

|||

*[[Whitewater Canal]] |

|||

*[[Indiana Central Canal]] |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

==Sources== |

|||

*{{cite book|author= Dunn, Jacob Piatt|title=Indiana and Indianans| year=©1919|publisher=The American Historical Society|location=Chicago & New York|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=GmcPryCCxFIC&|volume=V.I}} |

|||

*{{cite book|title=Canals for the Nation|author=Shaw, Ronald E.|year=1993|isbn= 0813108152|pubsliher=University Press of Kentucky}} |

|||

*{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=PCbZ8rS-84gC|title=Biographical and Historical Sketches of Early Indiana|author=Woollen, William Wesley|publisher=Ayer Publishing|year=1975|isbn=0405068964}} |

|||

{{-}} |

|||

{{Indiana history}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Revision as of 15:45, 10 October 2008

The Mammoth Internal Improvement Act was a law passed by the Indiana General Assembly in 1836 that greatly expanded the state of Indiana's internal improvement program. It added an additional $10 million (USD) to spending and funded several projects, including turnpikes, canals, and railroads. The following year the state economy was adversly affected by the Panic of 1837 and the overall project ended in a near total disaster for the state, which narrowly avoided bankrutpcy from the debt. By 1841, the the government could no longer make even the interest payment, and all the projects, except the largest canal, were handed over to the state's London creditors in exchange for a 50% reduction in debt. Again in 1846, the last project was handed over for another 50% in debt. Of the eight projects in the measure, none were completed by the state. Only two were finished by the creditors who took them over. The act is considered one of the greatest debacles in the history of the state.

Background

When the state of Indiana was formed in 1816, it was still a virtual wilderness, and settlement was limited to the southern periphery where easy access to the Ohio River provided a convenient means to export produce. The only significant road in the region was the Buffalo Trace, an old dirt bison trail that crossed the southern part of the state. After statehood several plans had been made to improve the transportation situation, like the creation of small local roads, the larger Michigan Road, and a failed attempted by the Indiana Canal Company to build a canal around the Falls of the Ohio. The national economy entered a recession following the Panic of 1819, and the states only two banks collapsed in the years that followed, ending the states improvement programs with having achieved little success.

The 1820s were spent repairing the state's finances and by 1831 the state had began to restart the internal improvement projects using land grants from teh federal government.[1] The Wabash and Erie Canal was started with local funds, but was taken over by the state that year, who continued to expand it. To fund the project, and in response to the closure of the Second Bank of the United States, the state established the Bank of Indiana. Bonds were issued through the bank to fund the early stages of the project, but it soon became apparent that it would take far more funds than could be obtained by bonds alone.

Passage of the law

In 1836, legislation was created by the Indiana General Assembly to dramatically expand the scope of the internal improvements. Over $2 million had already been burrowed, and the new bill proposed borrowing another $10 million. Seeing the success of canals in the eastern United States, it was believed that the projects would be very profitable for the state and that their revenue would quickly pay back the loans, and provide the funds to complete the projects.

For canals, the project called for the creation of a canal from Indianapolis to Evansville, called the Indiana Central Canal. It was intended to connect the Wabash and Erie Canal to the Ohio River. Funding was included for another canal to connect Indianapolis to the Wabash River in Lafayette known as the Whitewater Canal. Additional funding was granted to the Wabash and Erie Canal for expansion to Terre Haute. The canals received the majority of the funds from the bill, because it was believed that the canals could be constructed from local materials which would help boost the local economy.[2]

The bill also funded, but to a much lesser degree, a railroad connecting Madison to Indianapolis, the paving of the Buffalo Trace and renaming it the Vincennes Trace, the pavement of the remainder of the Michigan Road. The money from the project was gathered by mortgaging nine million acres of state owned land through the Bank of Indiana to creditors in London, with the bank being the actual bond holder, but the state responsible for insuring the bank.

Governor Noah Noble was a major supporter of the bill and it passed by the overwhelmingly Whig controlled General Assembly, although it was opposed by several prominent legislators including Dennis Pennington, James Whitcomb, Calvin Flethcer and John Durmont. Pennington believed the canals were a waste of money and would soon be made obsolete by the railroads.[3] Whitcomb outright rejected the idea of spending such a large sum of money, saying it would be impossible to pay back.[4]

The bill created a Board of Improvement and a Board of Funds Commissioners to oversee the projects. Two thirds of the funds were spent on the canals, with the Central Canal getting the most money.[5] Jesse L. Williams was named cheif engineer.[6]

Enactment

From the early onset it was noted that the project did not work together, but instead competed with each other for funds and land. This posed a problem for the government, because they did not provide enough funds to complete each of the projects, instead expecting them to start making money on their own.[7] Several small supplemental funding bills, adding approximately $2 million more dollars for use by the projects. The Wabash and Erie Canal was the most successful of the canal projects, and was profitable early on, but never to the extent expected. The Central Canal was major failure, with only a few miles of canal dug near Indianapolis before the project was out of money. The Whitewater Canal was p proceeding along well until it's earthen walls and feeder dams were the victims of muskrats who burrowed through the walls, causing hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages for which there was no money to repair. At the height of the operation, over ten thousand workers were employed on the canal projects.[8]

The rail line from Madison to Indianapolis was built much more cheaply than the canals. It was however, considerably over budget due to an increased costs of having to build a grade out of the low lying Ohio Valley onto the Indiana table land, so the project could not be finished. The Vincennes Trace was paved from new Albany to Paoli, with another 75 miles still requiring pavement.

The Panic of 1837 left the state in dire straites financially. By 1839 there was no money left for the projects and all work was halted. Work only continued on the Wabash and Erie where workers were paid with stock in the canal, and not cash. 140 miles of canal had been built for $8 million, and $1.5 million on 70 miles of railroad and turnpike. The state was left with a $13 million dollar debt, and only a trickle of tax revenue. James Lanier, president of the Bank of Indiana, was sent by Governor Samuel Bigger to negotiate with the state's London creditors in a hope to avoid total bankruptcy. He negotiated the transfer of all of the projects, except the Wabash and Erie, to the creditors in exchange for a 50% reduction in the debt to $6.5 million dollars.[9]

The Whigs suffered from the failure of the project and Democrat James Whitcomb, an opponent of the projects from the begining, was elected governor. He sent another representative to London and sold the Wabash and Erie for another 50% reduction in the debt to $3 million, ending the financial crisis. The result was a windfall for the Bank of Indiana, who ended with a 650% profit, but the state loosing millions. The state was, however, a 50% owner of the bank and recieving a $3.5 million dividend back from the bank which was put into the state's education fund.[10]

Aftermath

The creditors had taken the public works expecting that they could be quickly completed and become profitable. The Vincennes Trace was renamed the Paoli Pike, and operated for several years as a toll road. The Central Canal and Whitewater Canal were abandoned as a total loss, the expense to finish them was considered to be to great for their possible profitability. The Wabash and Erie Canal continued to operated for several decades, but quickly went into decline in the next decade as it was made obsolete by the railroads. The line from Madison to Indianapolis was also abandoned by the creditors and sold to entrepreneurs who were able to raise funds to complete the line. It was instantly profitable and went on to expand and connect to several other cities.

Although the government lost millions, there were significant benefits for the areas of the state where the projects succeeded. On average, land value in the state rose 400%, and the cost of shipping goods for farmers was drastically decreased, and increasing the profit on their goods. The investors in the Bank of Indiana also made substantial profits, and the investments served as the start of a modern economy for the state.[11] The act is often considered the greatest legislative debacle in the history of the state.

See also

Notes

Sources

- Dunn, Jacob Piatt (©1919). Indiana and Indianans. Vol. V.I. Chicago & New York: The American Historical Society.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - Shaw, Ronald E. (1993). Canals for the Nation. ISBN 0813108152.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|pubsliher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) - Woollen, William Wesley (1975). Biographical and Historical Sketches of Early Indiana. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 0405068964.