Talk:Dobrocin, Lower Silesian Voivodeship and Human rights in the Soviet Union: Difference between pages

talk page tag, Replaced: {{WikiProject Poland|class=stub|importance=}} → {{WikiProject Poland|class=stub|importance=low}} using AWB |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{POV|date=September 2008}} |

|||

{{WikiProject Poland|class=stub|importance=low}} |

|||

[[Image:Tanks return budapest 3 1956.jpg|thumb|160px|right| |

|||

Soviet abuse of human rights in Budapest on 4 November 1956]]The [[Soviet Union]] was a [[single-party state]] where the [[Communist Party of the Soviet Union|Communist Party]] ruled the country.<ref name="SovietConst"> [http://www.oefre.unibe.ch/law/icl/r100000_.html Constitution of the Soviet Union. Preamble] </ref> All key positions in the institutions of the state were occupied by members of the Communist Party. The state proclaimed its adherence to the [[Marxism-Leninism]] [[ideology]] and the entire population was mobilized in support of the state ideology and policies. Independent political activities were not tolerated, including the involvement of people with free [[labour union]]s, private [[corporation]]s, non-sanctioned [[Ecclesia (church)|churches]] or opposition [[political party|political parties]]. The regime maintained itself in [[political power]] by means of the [[secret police]], [[propaganda]] disseminated through the state-controlled [[mass media]], [[personality cult]], restriction of [[freedom of speech|free discussion and criticism]], the use of [[mass surveillance]], and widespread use of [[Terrorism|terror]] tactics, such as political purges and persecution of specific groups of people.{{or|date=September 2008}} |

|||

==Soviet concept of human rights== |

|||

{{POV-section|date=October 2008}} |

|||

According to [[Soviet constitution]], each individual was guaranteed civil rights, but had to sacrifice them and his/her desires to fulfill the needs of the [[collective]]. So, for example, open criticism of the Communist Party could not be allowed because it could hurt the interests of the state, society, and the progress of socialism. The Soviet concept of [[human rights]] focused on economic and social rights such as being able to have access to health care, get adequate nutrition, receive education at all levels, and be guaranteed employment.<ref name="SovietConst"/> The Soviets considered these to be the most important rights, which were not guaranteed by Western governments.<ref name=shiman>{{cite book | last = Shiman | first = David | title = Economic and Social Justice: A Human Rights Perspective | publisher = Amnesty International | year= 1999 | url = http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/edumat/hreduseries/tb1b/Section1/tb1-2.htm | isbn = 0967533406}}</ref> |

|||

==Criticism of Soviet rights and laws== |

|||

Critics claim that the Soviet legal system regarded law as an arm of politics and courts as agencies of the government <ref name="Pipes"/>. Extensive [[Extrajudicial punishment|extra-judiciary powers]] were given to the [[Chronology of Soviet secret police agencies|Soviet secret police agencies]]. According to [[Vladimir Lenin]], the purpose of early [[People's court (Soviet Union)|socialist courts]] was "not to eliminate [[Great Terror|terror]] ... but to substantiate it and legitimize in principle" <ref name="Pipes"/>. Historian [[Richard Pipes]] writes that the regime abolished Western legal concepts including the [[rule of law]], the [[civil liberties]], the [[Criminal justice|protection of law]] and [[Property rights|guarantees of property]].<ref> [[Richard Pipes]] (2001) ''Communism'' Weidenfled and Nicoloson. ISBN 0-297-64688-5 </ref><ref> [[Richard Pipes]] (1994) ''Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime''. Vintage. ISBN 0-679-76184-5., pages 401-403. </ref>. Western legal theory states that "it is the individual who is the beneficiary of [[human rights]] which are to be asserted ''against'' the government", whereas Soviet law claimed the opposite.<ref>Lambelet, Doriane. "The Contradiction Between Soviet and American Human Rights Doctrine: Reconciliation Through Perestroika and Pragmatism." 7 ''Boston University International Law Journal''. 1989. p. 61-62.</ref> |

|||

Crime was determined not as the infraction of law, but as any action which could threaten the Soviet state and society. For example, [[Speculation|a desire to make a profit]] could be interpreted as a criminal act done for self interest at the expensive of society, or, in the early period of the USSR, even as [[Counter-revolutionary|counter-revolutionary activity]] punishable by death.<ref name="Pipes"/> [[Dekulakization|The liquidation and deportation of millions peasants in 1928-31]] was carried out within the terms of Soviet Civil Code.<ref name="Pipes"> [[Richard Pipes]] ''Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime'', Vintage books, Random House Inc., New York, 1995, ISBN 0-394-50242-6, pages 402-403 </ref> Some early Soviet legal scholars even asserted that "criminal repression" may be applied in the absence of guilt."<ref name="Pipes"/>. As [[Martin Latsis]], chief of the Ukrainian [[Cheka]], explained during the civil war: |

|||

{{Quotation|"Do not look in the file of incriminating evidence to see whether or not the accused rose up against the Soviets with arms or words. Ask him instead to which [[social class|class]] he belongs, what is his background, his [[education]], his [[profession]]. These are the questions that will determine the fate of the accused. That is the meaning and essence of the [[Red Terror]]."<ref name="State"> [[Yevgenia Albats]] and Catherine A. Fitzpatrick. ''The State Within a State: The KGB and Its Hold on Russia - Past, Present, and Future'', 1994. ISBN 0-374-52738-5.</ref> }} |

|||

According to Richard Pipes, the purpose of [[Moscow Trials|public trials]] was "not to demonstrate the existence or absence of a crime - that was predetermined by the appropriate [[CPSU|party authorities]] - but to provide yet another forum for [[Soviet propaganda|political agitation and propaganda]] for the instruction of the citizenry. Defense lawyers, who had to be [[SPSU|party members]], were required to take their client's guilt for granted..."<ref name="Pipes"/> |

|||

==Political repression== |

|||

{{main|Soviet political repressions}} |

|||

The political repressions were practiced by the Soviet [[secret police]] services [[Cheka]], [[OGPU]] and [[NKVD]].<ref>[[Anton Antonov-Ovseenko]] ''[[Beria]]'' (Russian) Moscow, AST, 1999. [http://fictionbook.ru/author/antonov_ovseenko_anton/beriya/antonov_ovseenko_beriya.html Russian text online] </ref> An extensive network of civilian [[informants]] - either volunteers, or those forcibly recruited - was used to collect intelligence for the government and report cases of suspected dissent.<ref name="Informants"> Koehler, John O. Stasi: The Untold Story of the East German Secret Police. Westview Press. 2000. ISBN 0-8133-3744-5</ref> |

|||

Soviet political repression was a ''de facto'' and ''de jure'' system of prosecution of people who were or perceived to be enemies of the [[Soviet system]]. Its theoretical basis were the theory of [[Marxism]] about the [[class struggle]]. The term "repression", "terror", and other strong words were official working terms, since the [[dictatorship of the proletariat]] was supposed to suppress the resistance of other [[social class]]es which Marxism considered antagonistic to the class of [[proletariat]]. The legal basis of the repression was formalized into the [[Article 58 (RSFSR Penal Code)|Article 58 ]] in the code of [[RSFSR]] and similar articles for other [[Republics of the Soviet Union|Soviet republic]]s. [[Aggravation of class struggle under socialism]] was proclaimed during the Stalinist terror. |

|||

[[Image:Kersnovskaya Lucky Car.jpg|thumb|250px|right|[[Eufrosinia Kersnovskaya]] Birth in a prison car for [[Deportation of Romanians in the Soviet Union|Bessarabian deportees]]]] |

|||

===Chronology=== |

|||

The repressions were conducted in several consecutive waves known as [[Red Terror]], [[Dekulakization]], [[Great Purge]], [[Doctor's Plot]], and others. |

|||

During [[Red Terror]] and [[Collectivisation in the USSR|collectivization]] the entire "[[ruling class]]es" have been exterminated, including "rich people", and a significant part of [[intelligentsia]] and peasantry labeled as [[kulaks]]. The numerous victims of [[extrajudicial punishment]] were called the [[Enemy of the people|enemies of the people]]. The punishment by the state included [[summary execution]]s, [[torture]], sending innocent people to [[Gulag]], [[Involuntary settlements in the Soviet Union|involuntary settlement]], and [[Lishenets|stripping of citizen's rights]]. According to NKVD Orders [[NKVD Order No. 00486|No. 00486]] and [[NKVD Order No. 00689|No. 00689]], wives and family members were also punished if they were seen as being involved with their relative in the supposed crime. In 1941 the [[secret police]] forces conducted [[NKVD prisoner massacres|massacres of prisoners]] as the Soviets retreated from the German invasion.<ref name="Rhodes">{{en icon}} {{cite book | author=[[Richard Rhodes]] | year = 2002 | title = Masters of Death: The SS-Einsatzgruppen and the Invention of the Holocaust | publisher = Alfred A. Knopf | location = New York | id = ISBN 0-375-40900-9}} Despite the deportations, Barbarossa surprised the NKVD, whose jails and prisons in the invaded western territories were crowded with political prisoners. Rather than releasing their prisoners as they hurried to retreat during the first week of the war, the Soviet secret police simply killed them. NKVD prisoner executions in the first week after Barbarossa totaled some ten thousand in western Ukraine and more than nine thousand in [[Vinnytsia]], eastward toward [[Kiev]]. Comparable numbers of prisoners were executed in eastern Poland, [[Belarus|Byelorussia]], [[Lithuania]], [[Latvia]], and [[Estonia]]. The Soviet areas had already sustained losses numbering in the hundreds of thousands from the [[Great Purge|Stalinist purges of 1937-38]]. “It was not only the numbers of the executed,” historian Yury Boshyk writes of the evacuation murders, “but also the manner in which they died that shocked the populace. When the families of the arrested rushed to the prisons after the Soviet evacuation, they were aghast to find bodies so badly mutilated that many could not be identified. It was evident that many of the prisoners had been tortured before death; others were killed en masse.”</ref>. |

|||

After Stalin's death, the suppression of dissent was dramatically reduced and took new forms. The internal critics of the system were convicted for [[anti-Soviet agitation]] or as [[Parasitism (social offense)|"social parasites"]]. Others were labeled as mentally ill, having [[sluggishly progressing schizophrenia]] and incarcerated in "[[Psikhushka]]s", i.e. [[Punitive psychiatry in the Soviet Union|mental hospitals]] used by the Soviet authorities as prisons.<ref name="Psyche"> [http://hrw.org/reports/2002/china02/china0802-02.htm#P397_91143 The Soviet Case: Prelude to a Global Consensus on Psychiatry and Human Rights. Human Rights Watch. 2005]</ref> A few notable dissidents, such as [[Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn]], [[Vladimir Bukovsky]], and [[Andrei Sakharov]], were sent to internal or external exile. |

|||

===Suppression of uprisings=== |

|||

During the [[Russian Civil War]], anti-Bolshevik uprisings, like the [[Tambov rebellion|Tambov]] and [[Kronstadt rebellion|Kronstadt]] rebellions, were brutally suppressed by military force. During the Tambov rebellion, [[Bolshevik]] military forces used [[chemical weapons]] against rebelling peasants hiding in forests.<ref name="Tambov"> [http://gulag.ipvnews.org/article20061017.php B.V.Sennikov. ''Tambov rebellion and liquidation of peasants in Russia''], Publisher: Posev, 2004, ISBN 5-85824-152-2 [http://www.rusk.ru/vst.php?idar=321701 Full text in Russian] </ref> A Committee organized by [[Mikhail Tukhachevsky]] and [[Antonov-Ovseenko]] "took [[hostages]] on enormous scale, carried out executions, and set up [[death camps]] where prisoners were gassed" according to [[Black book of communism]]<ref>Courtois, Stephane; Werth, Nicolas; Panne, Jean-Louis; Paczkowski, Andrzej; Bartosek, Karel; Margolin, Jean-Louis & Kramer, Mark (1999). ''The [[Black Book of Communism]]: Crimes, Terror, Repression''. [[Harvard University Press]]. ISBN 0-674-07608-7 </ref> |

|||

===Ethnic cleansing accusations=== |

|||

{{main|Population transfer in the Soviet Union}} |

|||

[[Image:Holodomor.jpg|thumb|right|250px|[[Ukrainian Famine]] Victim, 1933]] |

|||

Entire nations have been collectively punished by the Soviet Government |

|||

for alleged collaboration with the enemy during [[World War II]]. |

|||

According to some historians, in legal terms the word "[[ethnic cleansing]]" or even "[[genocide]]" may be appropriate<ref name="State"/> [[Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide|because specific ethnic groups were targeted]]. At least nine of distinct ethnic-linguistic groups, including [[History of Germans in Russia and the Soviet Union|ethnic Germans]], ethnic [[Greeks]], [[Polish minority in the Soviet Union|ethnic Poles]], [[Crimean Tatars]], [[Balkars]], [[Chechen people|Chechen]]s, and [[Kalmyk deportations of 1944|Kalmyks]], were deported to remote unpopulated areas of [[Siberia]] and [[Kazakhstan]]. The [[Population transfer in the Soviet Union| ethnicity-targeted population transfers]] in the Soviet Union led to millions of deaths due to the inflicted hardships.<ref name="Conquest">[[Robert Conquest]] (1986) ''The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine.'' [[Oxford University Press]]. ISBN 0-19-505180-7. </ref> [[Deportation of Koreans in the Soviet Union|Koreans]] and [[Deportation of Romanians in the Soviet Union|Romanians]] were also deported. [[Mass operations of the NKVD]] were needed to [[deport]] hundreds of thousands of people. |

|||

===Deaths from famines=== |

|||

{{main|Holodomor}} |

|||

According to some historians, "the systematic use of famine as a weapon" was a "particular feature of many Communist regimes"<ref name="Black"/> and the deaths of 5 to 7 million people during the [[Soviet famine of 1932-1933]], including the [[Holodomor]] in the Ukraine, were caused by confiscating food from peasants and blocking the migration of starving population by the [[Government of the Soviet Union|Soviet government]].<ref name="Conquest"/> The overall number of [[peasant]]s who died in 1930–1937 from [[hunger]] and [[Soviet political repressions|repression]]s during [[Collectivisation in the USSR|collectivisation]] (including in [[Kavkaz]] and [[Kazakhstan]]) was at least 14.5 million, according to historian Robert Conquest.<ref name="Conquest"/> |

|||

More recent estimates, based on actual archival data, indicate that 2 to 3.5 million died in Ukraine during the Holodomor. Historians R. Davies and S. Wheatcroft estimate that, overall, 5.5 to 6.5 million Soviet people died due to famine in the 1930s.<ref name = years_of_hunger> {{cite book | last = Davies | first = R. W. | coauthors = Wheatcroft, S. G. | title = The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931-1933 (The Industrialization of Soviet Russia) | publisher = Macmillan | date = 2004 | pages = 400-1 | isbn = 0333311078}}</ref> According to them, the famine was an unintentional result of erroneous state policies in implementing collectivization combined with natural causes.<ref>Davies, R. & Wheatcroft, S., 440-1</ref> |

|||

===Loss of life=== |

|||

The number of people who died under Joseph Stalin's regime, including the famines, in the Soviet Union has been estimated as between 3.5 and 8 million by G. Ponton,<ref name="Ponton"> Ponton, G. (1994) ''The Soviet Era.''</ref> 6.6 million by V. V. Tsaplin,<ref name="Tsaplin"> Tsaplin, V.V. (1989) ''Statistika zherty naseleniya v 30e gody.''</ref> 9.5 million by [[Alec Nove]],<ref name="NoveStalin"> Nove, Alec. ''Victims of Stalinism: How Many?'', in ''Stalinist Terror: New Perspectives'' (edited by [[J. Arch Getty]] and Roberta T. Manning), [[Cambridge University Press]], 1993. ISBN 0-521-44670-8.</ref> 20 million by [[The Black Book of Communism]],<ref name="Black"> Bibliography: Courtois et al. The Black Book of Communism</ref> 50 million by [[Norman Davies]],<ref name="Davies"> Davies, Norman. ''Europe: A History'', Harper Perennial, 1998. ISBN 0-06-097468-0.</ref> and 61 million by [[R. J. Rummel]].<ref name="RummelStalin"> Bibliography: Rummel.</ref> The [[Guinness Book of Records]] claims that, overall, 66.7 million people were killed in the Soviet Union by state persecution from October 1917 through 1959 - under Lenin, Stalin, and Khrushchev.{{Fact|date=August 2008}} |

|||

The numbers of victims are inconsistent because they are determined using different criteria and methods and counted during different periods of time. Most recent publications are probably more reliable than estimates made during the [[Cold War]], since after the [[dissolution of the Soviet Union]], researchers gained access to Soviet archives. |

|||

==Freedom of expression, literature, and science== |

|||

{{main|Suppressed research in the Soviet Union}} |

|||

{{main|Socialist Realism}} |

|||

According to Soviet Criminal Code, Article 70, agitation or propaganda carried on for the purpose of weakening Soviet authority, circulating materials or literature that defamed the Soviet State and social system were punishable by imprisonment for a term of 2-5 years and for a second offense, punishable for a term of 3-10 years. <ref name="BDDSU">[http://books.google.com/books?id=1IQzecjGQX0C&dq Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in the Soviet Union, 1956-1975 By S. P. de Boer, E. J. Driessen, H. L. Verhaar; ISBN 9024725380; p. 652]</ref><br /> |

|||

[[Censorship in the Soviet Union]] was pervasive and strictly enforced.<ref name="FreeSpeech"> [http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/cshome.html A Country Study: Soviet Union (Former). Chapter 9 - Mass Media and the Arts. The Library of Congress. Country Studies] </ref> This gave rise to [[Samizdat]], a clandestine copying and distribution of government-suppressed literature. |

|||

[[Art]], [[literature]], [[education]], and [[science]] were placed under a strict ideological scrutiny, since they were supposed to serve the interests of the victorious [[proletariat]]. [[Socialist realism]] is an example of such teleologically-oriented art that promoted [[socialism]] and [[communism]]. All humanities and social sciences were tested for strict accordance with [[historical materialism]]. |

|||

All natural sciences had to be founded on the philosophical base of [[dialectical materialism]]. Many scientific disciplines, such as [[genetics]], [[cybernetics]], and [[comparative linguistics]], were [[Suppressed research in the Soviet Union|suppressed in the Soviet Union]] during some periods, condemned as "[[bourgeois pseudoscience]]", and replaced by real [[pseudoscience]], such as [[Lysenkoism]]. Many prominent scientists during Stalin's rule were declared to be "[[Wrecking (Soviet crime)|wrecklers]]" or [[enemy of the people]] and imprisoned. Under Stalin, some scientists worked as prisoners in "[[Sharashka]]s", i.e. research and development laboratories within the [[Gulag]] labor camp system. |

|||

Every large enterprise or institution of the Soviet Union had [[First Department]] run by [[KGB]] people responsible for secrecy and political security of the workplace. |

|||

==Right to vote== |

|||

{{main|Soviet democracy}} |

|||

According to [[Soviet propaganda|communist ideologists]], the [[Soviet democracy|Soviet political system]] was a true democracy, where [[workers' councils]] called "soviets" represented the will of the [[working class]]. In particular, the [[1936 Soviet Constitution|Soviet Constitution of 1936]] guaranteed direct [[universal suffrage]] with the [[secret ballot]]. However all candidates had been selected by Communist party organizations, at least before the June 1987 elections. Historian [[Robert Conquest]] described this system as |

|||

{{Quotation|"a set of phantom institutions and arrangements which put a human face on the hideous realities: [[1936 Soviet Constitution|a model constitution]] adopted in [[Great purge|a worst period of terror]] and guaranteeing human rights, elections in which there was only one candidate, and in which 99 percent voted; a parliament at which no hand was ever raised in opposition or abstention."<ref name="reflections"> [[Robert Conquest]] ''Reflections on a Ravaged Century'' (2000) ISBN 0-393-04818-7, page 97 </ref>}} |

|||

==Property rights== |

|||

[[Personal property]] was allowed, with certain limitations. All [[real property]] belonged to the state and society.<ref name="SovietConst"/> Unauthorized possession of foreign [[currency]] was forbidden and prosecuted as [[criminal offense]]. |

|||

==Freedoms of assembly and association== |

|||

Freedoms of [[Freedom of assembly|assembly]] and [[Freedom of association|association]] did not exist.{{Or|date=August 2008}} Workers were not allowed to organize free [[trade union]]s. [[Trade unions in the Soviet Union|All existing trade unions]] were organized and controlled by the state.<ref name="Unions"> [http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/cshome.html A Country Study: Soviet Union (Former). Chapter 5. Trade Unions. The Library of Congress. Country Studies. 2005.] </ref> All political youth organizations, such as [[Pioneer movement]] and [[Komsomol]] served to enforce the policies of the Communist Party. |

|||

According to Soviet criminal code participation in an anti-Soviet organization was punished in accordance with Article 64 -treason punishable up to [[Death penalty]] <ref name="BDDSU"/> |

|||

==Freedom of religion== |

|||

[[Image:Astrakhan Temple of St Vladimira.jpg|thumb|Temple of St Vladimir. It was turned into bus station in Soviet time.]] |

|||

{{main|Religion in the Soviet Union}} |

|||

The Soviet government promoted atheism. The stated goal was control, suppression, and, ultimately, the elimination of religious beliefs, which were seen as backward and disuniting. Atheism was propagated through schools, communist organizations, and the media. Movements, such as the [[Society of the Godless]], were created. All religious movements were either prosecuted or controlled by the state and [[KGB]].{{fact|date=September 2008}} Nonetheless many still did practice religion, especially in the Asian republics. |

|||

==Freedom of movement== |

|||

{{main|Passport system in the Soviet Union}} |

|||

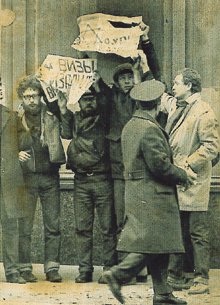

[[Image:19730110 Soviet refuseniks demonstrate at MVD.jpg|thumb|left|January 10, 1973. Jewish refuseniks demonstrate in front of the Ministry of Internal Affairs for the right to emigrate to Israel]]Emigration and any travel abroad were not allowed without an explicit permission from the government. People who were not allowed to leave the country are known as [[Refusenik (Soviet Union)|"refuseniks"]]. |

|||

According to the Soviet Criminal Code, Article 64. flight abroad or refusal to return from abroad among other offenses was [[Treason]] that was punishable by imprisonment for a term of 10-15 years with confiscation of property or by death with confiscation of property. <ref name="BDDSU"/> |

|||

[[Passport system in the Soviet Union]] restricted migration of citizens within the country through "[[propiska]]" (residential permit/registration system) and use of [[internal passport]]s. For a long period of the Soviet history peasants did not have [[internal passport]]s and could not move into towns without permission. Many former inmates received "[[Wolf ticket (Russia)|wolf ticket]]" and were allowed to live only at [[101st kilometre|101 km away from city borders]]. Travel to [[Closed city|closed cities]] and to the regions near USSR state borders was strongly restricted. Illegal exit abroad was punishable by imprisonment for a term of 1-3 years. <ref name="BDDSU"/> |

|||

==Human rights organizations and activists in USSR== |

|||

{{Expand|date=August 2008}} |

|||

*[[Action Group for the Defence of Civil rights in the USSR]] was founded in May 1969. The organization petitioned on behalf of the victims of Soviet government repressions, was dissolved after the arrest and trial of its leading member P.I. Jakir. |

|||

*In November 1970 the [[Moscow Human Rights Committee]] was founded by [[Andrei Sakharov]] and his colleagues to publicize Soviet violations of human rights. |

|||

*USSR's section of [[Amnesty International]] was founded on October 6 1973 by 11 Moscow intellectuals and was registered in September 1974 by the Amnesty international Secretariat in London. |

|||

*The [[Moscow Helsinki Group]] was founded in 1976 to monitor the Soviet Union's compliance with the [[Helsinki Final Act]] of 1975 that included clauses calling for the recognition of universal human rights. |

|||

*The [[Ukrainian Helsinki Group]] was founded in November 1976 to monitor [[human rights]] in [[Ukraine]].<ref>[http://archive.khpg.org.ua/en/index.php?id=1127288239 Museum of dissident movement in Ukraine]</ref> The group was active until 1981 when all members were jailed. |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

==Bibliography== |

|||

*Applebaum, Anne (2003) ''[[Gulag: A History]]''. Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-0056-1 |

|||

*Conquest, Robert (1991) ''[[The Great Terror]]: A Reassessment''. Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-507132-8. |

|||

*Conquest, Robert (1986) ''The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine''. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505180-7. |

|||

*Courtois, Stephane; Werth, Nicolas; Panne, Jean-Louis; Paczkowski, Andrzej; Bartosek, Karel; Margolin, Jean-Louis & Kramer, Mark (1999). ''The [[Black Book of Communism]]: Crimes, Terror, Repression''. [[Harvard University Press]]. ISBN 0-674-07608-7. |

|||

*Khlevniuk, Oleg & Kozlov, Vladimir (2004) ''The History of the Gulag : From Collectivization to the Great Terror (Annals of Communism Series)'' Yale University Pres. ISBN 0-300-09284-9. |

|||

*Pipes, Richard (2001) ''Communism'' Weidenfled and Nicoloson. ISBN 0-297-64688-5 |

|||

*Pipes, Richard (1994) ''Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime''. Vintage. ISBN 0-679-76184-5. |

|||

*Rummel, R.J. (1996) ''Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1917''. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-887-3. |

|||

*Yakovlev, Alexander (2004). ''A Century of Violence in Soviet Russia.'' Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10322-0. |

|||

==External links== |

|||

*[http://www.gmu.edu/departments/economics/bcaplan/museum/musframe.htm Museum of Communism] |

|||

**[http://www.gmu.edu/departments/economics/bcaplan/museum/faqframe.htm Museum of Communism FAQ] |

|||

*[http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/COM.ART.HTM How many did the Communist regimes murder?] |

|||

*[http://www.victimsofcommunism.org/about/ The Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation] |

|||

*[[Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe]] (2006) [http://assembly.coe.int/Mainf.asp?link=/Documents/AdoptedText/ta06/Eres1481.htm Res. 1481 Need for international condemnation of crimes of totalitarian communist regimes] |

|||

*[http://www.angelfire.com/de/Cerskus/english/links1.html Crimes of Soviet Communists] — Wide collection of sources and links |

|||

*[http://www.demokratizatsiya.org/Dem%20Archives/DEM%2001-04%20armes.pdf Chekists in Cassocks: The Orthodox Church and the KGB] - by Keith Armes |

|||

*[http://www.romanitas.ru/eng/THE%20BATTLE%20FOR%20THE%20RUSSIAN%20ORTHODOX%20CHURCH.htm The battle for the Russian Orthodox Church] - by Vladimir Moss |

|||

*[http://cmpage.org/betrayal/chapt5.html The Betrayal of the Church] - by Edmund W. Robb and Julia Robb, 1986 |

|||

==See also== |

|||

*[[Soviet democracy]] |

|||

*[[Human rights in Russia]] |

|||

*[[Stalinism]] |

|||

*[[Totalitarianism]] |

|||

*[[Criticisms of Communist party rule]] |

|||

===For other articles on the topic see: === |

|||

*[[:Category:Political repression in the Soviet Union]] |

|||

*[[:Category:Victims of Soviet repressions]] |

|||

*[[:Category:Gulag]] |

|||

*[[:Category:Forced migration in the Soviet Union]] |

|||

*[[:Category:Soviet and Russian intelligence agencies]] |

|||

*[[:Category:Law enforcement in the Soviet Union]] |

|||

*[[:Category:NKVD]] |

|||

*[[:Category:Soviet phraseology]] |

|||

*[[:Category:Rebellions in Russia]] |

|||

*[[:Category:Moscow Helsinki Watch Group]] |

|||

*[[:Category:Soviet dissidents]] |

|||

*[[:Category:Sharashka inmates]] |

|||

*[[:Category:Prisons in Russia]] |

|||

{{Human rights}} |

|||

[[Category:Human rights by country|Soviet Union]] |

|||

[[Category:Political repression in the Soviet Union]] |

|||

[[Category:Soviet state]] |

|||

[[Category:Soviet Union]] |

|||

[[es:Derechos humanos en la URSS]] |

|||

[[ru:Права человека в СССР]] |

|||

Revision as of 13:24, 11 October 2008

The Soviet Union was a single-party state where the Communist Party ruled the country.[1] All key positions in the institutions of the state were occupied by members of the Communist Party. The state proclaimed its adherence to the Marxism-Leninism ideology and the entire population was mobilized in support of the state ideology and policies. Independent political activities were not tolerated, including the involvement of people with free labour unions, private corporations, non-sanctioned churches or opposition political parties. The regime maintained itself in political power by means of the secret police, propaganda disseminated through the state-controlled mass media, personality cult, restriction of free discussion and criticism, the use of mass surveillance, and widespread use of terror tactics, such as political purges and persecution of specific groups of people.[original research?]

Soviet concept of human rights

According to Soviet constitution, each individual was guaranteed civil rights, but had to sacrifice them and his/her desires to fulfill the needs of the collective. So, for example, open criticism of the Communist Party could not be allowed because it could hurt the interests of the state, society, and the progress of socialism. The Soviet concept of human rights focused on economic and social rights such as being able to have access to health care, get adequate nutrition, receive education at all levels, and be guaranteed employment.[1] The Soviets considered these to be the most important rights, which were not guaranteed by Western governments.[2]

Criticism of Soviet rights and laws

Critics claim that the Soviet legal system regarded law as an arm of politics and courts as agencies of the government [3]. Extensive extra-judiciary powers were given to the Soviet secret police agencies. According to Vladimir Lenin, the purpose of early socialist courts was "not to eliminate terror ... but to substantiate it and legitimize in principle" [3]. Historian Richard Pipes writes that the regime abolished Western legal concepts including the rule of law, the civil liberties, the protection of law and guarantees of property.[4][5]. Western legal theory states that "it is the individual who is the beneficiary of human rights which are to be asserted against the government", whereas Soviet law claimed the opposite.[6]

Crime was determined not as the infraction of law, but as any action which could threaten the Soviet state and society. For example, a desire to make a profit could be interpreted as a criminal act done for self interest at the expensive of society, or, in the early period of the USSR, even as counter-revolutionary activity punishable by death.[3] The liquidation and deportation of millions peasants in 1928-31 was carried out within the terms of Soviet Civil Code.[3] Some early Soviet legal scholars even asserted that "criminal repression" may be applied in the absence of guilt."[3]. As Martin Latsis, chief of the Ukrainian Cheka, explained during the civil war:

"Do not look in the file of incriminating evidence to see whether or not the accused rose up against the Soviets with arms or words. Ask him instead to which class he belongs, what is his background, his education, his profession. These are the questions that will determine the fate of the accused. That is the meaning and essence of the Red Terror."[7]

According to Richard Pipes, the purpose of public trials was "not to demonstrate the existence or absence of a crime - that was predetermined by the appropriate party authorities - but to provide yet another forum for political agitation and propaganda for the instruction of the citizenry. Defense lawyers, who had to be party members, were required to take their client's guilt for granted..."[3]

Political repression

The political repressions were practiced by the Soviet secret police services Cheka, OGPU and NKVD.[8] An extensive network of civilian informants - either volunteers, or those forcibly recruited - was used to collect intelligence for the government and report cases of suspected dissent.[9]

Soviet political repression was a de facto and de jure system of prosecution of people who were or perceived to be enemies of the Soviet system. Its theoretical basis were the theory of Marxism about the class struggle. The term "repression", "terror", and other strong words were official working terms, since the dictatorship of the proletariat was supposed to suppress the resistance of other social classes which Marxism considered antagonistic to the class of proletariat. The legal basis of the repression was formalized into the Article 58 in the code of RSFSR and similar articles for other Soviet republics. Aggravation of class struggle under socialism was proclaimed during the Stalinist terror.

Chronology

The repressions were conducted in several consecutive waves known as Red Terror, Dekulakization, Great Purge, Doctor's Plot, and others.

During Red Terror and collectivization the entire "ruling classes" have been exterminated, including "rich people", and a significant part of intelligentsia and peasantry labeled as kulaks. The numerous victims of extrajudicial punishment were called the enemies of the people. The punishment by the state included summary executions, torture, sending innocent people to Gulag, involuntary settlement, and stripping of citizen's rights. According to NKVD Orders No. 00486 and No. 00689, wives and family members were also punished if they were seen as being involved with their relative in the supposed crime. In 1941 the secret police forces conducted massacres of prisoners as the Soviets retreated from the German invasion.[10].

After Stalin's death, the suppression of dissent was dramatically reduced and took new forms. The internal critics of the system were convicted for anti-Soviet agitation or as "social parasites". Others were labeled as mentally ill, having sluggishly progressing schizophrenia and incarcerated in "Psikhushkas", i.e. mental hospitals used by the Soviet authorities as prisons.[11] A few notable dissidents, such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Vladimir Bukovsky, and Andrei Sakharov, were sent to internal or external exile.

Suppression of uprisings

During the Russian Civil War, anti-Bolshevik uprisings, like the Tambov and Kronstadt rebellions, were brutally suppressed by military force. During the Tambov rebellion, Bolshevik military forces used chemical weapons against rebelling peasants hiding in forests.[12] A Committee organized by Mikhail Tukhachevsky and Antonov-Ovseenko "took hostages on enormous scale, carried out executions, and set up death camps where prisoners were gassed" according to Black book of communism[13]

Ethnic cleansing accusations

Entire nations have been collectively punished by the Soviet Government for alleged collaboration with the enemy during World War II.

According to some historians, in legal terms the word "ethnic cleansing" or even "genocide" may be appropriate[7] because specific ethnic groups were targeted. At least nine of distinct ethnic-linguistic groups, including ethnic Germans, ethnic Greeks, ethnic Poles, Crimean Tatars, Balkars, Chechens, and Kalmyks, were deported to remote unpopulated areas of Siberia and Kazakhstan. The ethnicity-targeted population transfers in the Soviet Union led to millions of deaths due to the inflicted hardships.[14] Koreans and Romanians were also deported. Mass operations of the NKVD were needed to deport hundreds of thousands of people.

Deaths from famines

According to some historians, "the systematic use of famine as a weapon" was a "particular feature of many Communist regimes"[15] and the deaths of 5 to 7 million people during the Soviet famine of 1932-1933, including the Holodomor in the Ukraine, were caused by confiscating food from peasants and blocking the migration of starving population by the Soviet government.[14] The overall number of peasants who died in 1930–1937 from hunger and repressions during collectivisation (including in Kavkaz and Kazakhstan) was at least 14.5 million, according to historian Robert Conquest.[14]

More recent estimates, based on actual archival data, indicate that 2 to 3.5 million died in Ukraine during the Holodomor. Historians R. Davies and S. Wheatcroft estimate that, overall, 5.5 to 6.5 million Soviet people died due to famine in the 1930s.[16] According to them, the famine was an unintentional result of erroneous state policies in implementing collectivization combined with natural causes.[17]

Loss of life

The number of people who died under Joseph Stalin's regime, including the famines, in the Soviet Union has been estimated as between 3.5 and 8 million by G. Ponton,[18] 6.6 million by V. V. Tsaplin,[19] 9.5 million by Alec Nove,[20] 20 million by The Black Book of Communism,[15] 50 million by Norman Davies,[21] and 61 million by R. J. Rummel.[22] The Guinness Book of Records claims that, overall, 66.7 million people were killed in the Soviet Union by state persecution from October 1917 through 1959 - under Lenin, Stalin, and Khrushchev.[citation needed]

The numbers of victims are inconsistent because they are determined using different criteria and methods and counted during different periods of time. Most recent publications are probably more reliable than estimates made during the Cold War, since after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, researchers gained access to Soviet archives.

Freedom of expression, literature, and science

According to Soviet Criminal Code, Article 70, agitation or propaganda carried on for the purpose of weakening Soviet authority, circulating materials or literature that defamed the Soviet State and social system were punishable by imprisonment for a term of 2-5 years and for a second offense, punishable for a term of 3-10 years. [23]

Censorship in the Soviet Union was pervasive and strictly enforced.[24] This gave rise to Samizdat, a clandestine copying and distribution of government-suppressed literature.

Art, literature, education, and science were placed under a strict ideological scrutiny, since they were supposed to serve the interests of the victorious proletariat. Socialist realism is an example of such teleologically-oriented art that promoted socialism and communism. All humanities and social sciences were tested for strict accordance with historical materialism.

All natural sciences had to be founded on the philosophical base of dialectical materialism. Many scientific disciplines, such as genetics, cybernetics, and comparative linguistics, were suppressed in the Soviet Union during some periods, condemned as "bourgeois pseudoscience", and replaced by real pseudoscience, such as Lysenkoism. Many prominent scientists during Stalin's rule were declared to be "wrecklers" or enemy of the people and imprisoned. Under Stalin, some scientists worked as prisoners in "Sharashkas", i.e. research and development laboratories within the Gulag labor camp system.

Every large enterprise or institution of the Soviet Union had First Department run by KGB people responsible for secrecy and political security of the workplace.

Right to vote

According to communist ideologists, the Soviet political system was a true democracy, where workers' councils called "soviets" represented the will of the working class. In particular, the Soviet Constitution of 1936 guaranteed direct universal suffrage with the secret ballot. However all candidates had been selected by Communist party organizations, at least before the June 1987 elections. Historian Robert Conquest described this system as

"a set of phantom institutions and arrangements which put a human face on the hideous realities: a model constitution adopted in a worst period of terror and guaranteeing human rights, elections in which there was only one candidate, and in which 99 percent voted; a parliament at which no hand was ever raised in opposition or abstention."[25]

Property rights

Personal property was allowed, with certain limitations. All real property belonged to the state and society.[1] Unauthorized possession of foreign currency was forbidden and prosecuted as criminal offense.

Freedoms of assembly and association

Freedoms of assembly and association did not exist.[original research?] Workers were not allowed to organize free trade unions. All existing trade unions were organized and controlled by the state.[26] All political youth organizations, such as Pioneer movement and Komsomol served to enforce the policies of the Communist Party.

According to Soviet criminal code participation in an anti-Soviet organization was punished in accordance with Article 64 -treason punishable up to Death penalty [23]

Freedom of religion

The Soviet government promoted atheism. The stated goal was control, suppression, and, ultimately, the elimination of religious beliefs, which were seen as backward and disuniting. Atheism was propagated through schools, communist organizations, and the media. Movements, such as the Society of the Godless, were created. All religious movements were either prosecuted or controlled by the state and KGB.[citation needed] Nonetheless many still did practice religion, especially in the Asian republics.

Freedom of movement

Emigration and any travel abroad were not allowed without an explicit permission from the government. People who were not allowed to leave the country are known as "refuseniks".

According to the Soviet Criminal Code, Article 64. flight abroad or refusal to return from abroad among other offenses was Treason that was punishable by imprisonment for a term of 10-15 years with confiscation of property or by death with confiscation of property. [23]

Passport system in the Soviet Union restricted migration of citizens within the country through "propiska" (residential permit/registration system) and use of internal passports. For a long period of the Soviet history peasants did not have internal passports and could not move into towns without permission. Many former inmates received "wolf ticket" and were allowed to live only at 101 km away from city borders. Travel to closed cities and to the regions near USSR state borders was strongly restricted. Illegal exit abroad was punishable by imprisonment for a term of 1-3 years. [23]

Human rights organizations and activists in USSR

- Action Group for the Defence of Civil rights in the USSR was founded in May 1969. The organization petitioned on behalf of the victims of Soviet government repressions, was dissolved after the arrest and trial of its leading member P.I. Jakir.

- In November 1970 the Moscow Human Rights Committee was founded by Andrei Sakharov and his colleagues to publicize Soviet violations of human rights.

- USSR's section of Amnesty International was founded on October 6 1973 by 11 Moscow intellectuals and was registered in September 1974 by the Amnesty international Secretariat in London.

- The Moscow Helsinki Group was founded in 1976 to monitor the Soviet Union's compliance with the Helsinki Final Act of 1975 that included clauses calling for the recognition of universal human rights.

- The Ukrainian Helsinki Group was founded in November 1976 to monitor human rights in Ukraine.[27] The group was active until 1981 when all members were jailed.

References

- ^ a b c Constitution of the Soviet Union. Preamble

- ^ Shiman, David (1999). Economic and Social Justice: A Human Rights Perspective. Amnesty International. ISBN 0967533406.

- ^ a b c d e f Richard Pipes Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime, Vintage books, Random House Inc., New York, 1995, ISBN 0-394-50242-6, pages 402-403

- ^ Richard Pipes (2001) Communism Weidenfled and Nicoloson. ISBN 0-297-64688-5

- ^ Richard Pipes (1994) Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime. Vintage. ISBN 0-679-76184-5., pages 401-403.

- ^ Lambelet, Doriane. "The Contradiction Between Soviet and American Human Rights Doctrine: Reconciliation Through Perestroika and Pragmatism." 7 Boston University International Law Journal. 1989. p. 61-62.

- ^ a b Yevgenia Albats and Catherine A. Fitzpatrick. The State Within a State: The KGB and Its Hold on Russia - Past, Present, and Future, 1994. ISBN 0-374-52738-5.

- ^ Anton Antonov-Ovseenko Beria (Russian) Moscow, AST, 1999. Russian text online

- ^ Koehler, John O. Stasi: The Untold Story of the East German Secret Police. Westview Press. 2000. ISBN 0-8133-3744-5

- ^ Template:En icon Richard Rhodes (2002). Masters of Death: The SS-Einsatzgruppen and the Invention of the Holocaust. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40900-9. Despite the deportations, Barbarossa surprised the NKVD, whose jails and prisons in the invaded western territories were crowded with political prisoners. Rather than releasing their prisoners as they hurried to retreat during the first week of the war, the Soviet secret police simply killed them. NKVD prisoner executions in the first week after Barbarossa totaled some ten thousand in western Ukraine and more than nine thousand in Vinnytsia, eastward toward Kiev. Comparable numbers of prisoners were executed in eastern Poland, Byelorussia, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. The Soviet areas had already sustained losses numbering in the hundreds of thousands from the Stalinist purges of 1937-38. “It was not only the numbers of the executed,” historian Yury Boshyk writes of the evacuation murders, “but also the manner in which they died that shocked the populace. When the families of the arrested rushed to the prisons after the Soviet evacuation, they were aghast to find bodies so badly mutilated that many could not be identified. It was evident that many of the prisoners had been tortured before death; others were killed en masse.”

- ^ The Soviet Case: Prelude to a Global Consensus on Psychiatry and Human Rights. Human Rights Watch. 2005

- ^ B.V.Sennikov. Tambov rebellion and liquidation of peasants in Russia, Publisher: Posev, 2004, ISBN 5-85824-152-2 Full text in Russian

- ^ Courtois, Stephane; Werth, Nicolas; Panne, Jean-Louis; Paczkowski, Andrzej; Bartosek, Karel; Margolin, Jean-Louis & Kramer, Mark (1999). The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-07608-7

- ^ a b c Robert Conquest (1986) The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505180-7.

- ^ a b Bibliography: Courtois et al. The Black Book of Communism

- ^ Davies, R. W. (2004). The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931-1933 (The Industrialization of Soviet Russia). Macmillan. pp. 400–1. ISBN 0333311078.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Davies, R. & Wheatcroft, S., 440-1

- ^ Ponton, G. (1994) The Soviet Era.

- ^ Tsaplin, V.V. (1989) Statistika zherty naseleniya v 30e gody.

- ^ Nove, Alec. Victims of Stalinism: How Many?, in Stalinist Terror: New Perspectives (edited by J. Arch Getty and Roberta T. Manning), Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-521-44670-8.

- ^ Davies, Norman. Europe: A History, Harper Perennial, 1998. ISBN 0-06-097468-0.

- ^ Bibliography: Rummel.

- ^ a b c d Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in the Soviet Union, 1956-1975 By S. P. de Boer, E. J. Driessen, H. L. Verhaar; ISBN 9024725380; p. 652

- ^ A Country Study: Soviet Union (Former). Chapter 9 - Mass Media and the Arts. The Library of Congress. Country Studies

- ^ Robert Conquest Reflections on a Ravaged Century (2000) ISBN 0-393-04818-7, page 97

- ^ A Country Study: Soviet Union (Former). Chapter 5. Trade Unions. The Library of Congress. Country Studies. 2005.

- ^ Museum of dissident movement in Ukraine

Bibliography

- Applebaum, Anne (2003) Gulag: A History. Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-0056-1

- Conquest, Robert (1991) The Great Terror: A Reassessment. Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-507132-8.

- Conquest, Robert (1986) The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505180-7.

- Courtois, Stephane; Werth, Nicolas; Panne, Jean-Louis; Paczkowski, Andrzej; Bartosek, Karel; Margolin, Jean-Louis & Kramer, Mark (1999). The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-07608-7.

- Khlevniuk, Oleg & Kozlov, Vladimir (2004) The History of the Gulag : From Collectivization to the Great Terror (Annals of Communism Series) Yale University Pres. ISBN 0-300-09284-9.

- Pipes, Richard (2001) Communism Weidenfled and Nicoloson. ISBN 0-297-64688-5

- Pipes, Richard (1994) Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime. Vintage. ISBN 0-679-76184-5.

- Rummel, R.J. (1996) Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1917. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-887-3.

- Yakovlev, Alexander (2004). A Century of Violence in Soviet Russia. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10322-0.

External links

- Museum of Communism

- How many did the Communist regimes murder?

- The Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation

- Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (2006) Res. 1481 Need for international condemnation of crimes of totalitarian communist regimes

- Crimes of Soviet Communists — Wide collection of sources and links

- Chekists in Cassocks: The Orthodox Church and the KGB - by Keith Armes

- The battle for the Russian Orthodox Church - by Vladimir Moss

- The Betrayal of the Church - by Edmund W. Robb and Julia Robb, 1986

See also

- Soviet democracy

- Human rights in Russia

- Stalinism

- Totalitarianism

- Criticisms of Communist party rule

For other articles on the topic see:

- Category:Political repression in the Soviet Union

- Category:Victims of Soviet repressions

- Category:Gulag

- Category:Forced migration in the Soviet Union

- Category:Soviet and Russian intelligence agencies

- Category:Law enforcement in the Soviet Union

- Category:NKVD

- Category:Soviet phraseology

- Category:Rebellions in Russia

- Category:Moscow Helsinki Watch Group

- Category:Soviet dissidents

- Category:Sharashka inmates

- Category:Prisons in Russia