Tasmaniosaurus: Difference between revisions

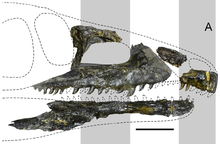

Skull section almost complete |

More |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''''Tasmaniosaurus''''' ('Lizard from Tasmania') is an [[Extinction|extinct]] [[genus]] of [[Archosauromorpha|archosauromorph]] reptile known from the [[Knocklofty Formation]] ([[Early Triassic]]) of [[West Hobart]], [[Tasmania]], [[Australia]]. The [[type species]] is ''T. triassicus''. |

'''''Tasmaniosaurus''''' ('Lizard from Tasmania', although this genus is not a true [[lizard]]) is an [[Extinction|extinct]] [[genus]] of [[Archosauromorpha|archosauromorph]] reptile known from the [[Knocklofty Formation]] ([[Early Triassic]]) of [[West Hobart]], [[Tasmania]], [[Australia]]. The [[type species]] is ''T. triassicus''. This genus is notable not only due to being one of the most complete Australian Triassic reptiles known, but also due to being a very close relative of [[Archosauriformes]]. Once believed to be a [[Proterosuchidae|proterosuchid]], this taxon is now believed to have been intermediate between advanced non-archosauriform archosauromorphs such as ''[[Prolacerta]]'', and basal archosauriforms such as ''[[Proterosuchus]]''. Features traditionally used to define [[Archosaur|Archosauria]] and later Archosauriformes, such as the presence of an [[antorbital fenestra]] and serrated teeth, are now known to have evolved prior to those groups due to their presence in ''Tasmaniosaurus''.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

== History and Classification == |

== History and Classification == |

||

First named as a ''[[nomen nudum]]'' in 1974, the genus received a formal description by Camp & Banks in 1978.<ref name="CB78">{{cite journal |last=Camp |first=C. L. |author2=Banks, M. R. |year=1978 |title=A proterosuchian reptile from the Early Triassic of Tasmania |journal=Alcheringa |volume=2 |pages=143–158 |doi=10.1080/03115517808619085}}</ref><ref name="CJW74">{{cite journal |last=Cosgriff |first=J. W. |year=1974 |title=Lower Triassic Temnospondyli of Tasmania |journal=Special Papers of the Geological Society of America |volume=149 |pages=1–134 |doi=10.1130/spe149-p1}}</ref>These descriptions considered it a [[Proterosuchidae|proterosuchid]] [[archosaur]]. A rediscription by Thulborn in 1986 agreed with this interpretation.<ref name="TRA86">{{cite journal |last=Thulborn |first=R. A. |year=1986 |title=The Australian Triassic reptile ''Tasmaniosaurus triassicus'' (Thecodontia: Proterosuchia) |journal=Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology |volume=6 |issue=2 |pages=123–142 |doi=10.1080/02724634.1986.10011606}}</ref> Since then, [[Cladistics|cladistic]] work has redefined the term "[[archosaur]]" to only include bird-line archosaurs ([[Avemetatarsalia]]) and crocodile-line archosaurs ([[Pseudosuchia]]). As proterosuchids evolved prior to the split between these two groups, they are not considered archosurs using this definition. In lieu of this revelation, the clade |

First named as a ''[[nomen nudum]]'' in 1974, the genus received a formal description by Camp & Banks in 1978.<ref name="CB78">{{cite journal |last=Camp |first=C. L. |author2=Banks, M. R. |year=1978 |title=A proterosuchian reptile from the Early Triassic of Tasmania |journal=Alcheringa |volume=2 |pages=143–158 |doi=10.1080/03115517808619085}}</ref><ref name="CJW74">{{cite journal |last=Cosgriff |first=J. W. |year=1974 |title=Lower Triassic Temnospondyli of Tasmania |journal=Special Papers of the Geological Society of America |volume=149 |pages=1–134 |doi=10.1130/spe149-p1}}</ref>These descriptions considered it a [[Proterosuchidae|proterosuchid]] [[archosaur]]. A rediscription by Thulborn in 1986 agreed with this interpretation.<ref name="TRA86">{{cite journal |last=Thulborn |first=R. A. |year=1986 |title=The Australian Triassic reptile ''Tasmaniosaurus triassicus'' (Thecodontia: Proterosuchia) |journal=Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology |volume=6 |issue=2 |pages=123–142 |doi=10.1080/02724634.1986.10011606}}</ref> Since then, [[Cladistics|cladistic]] work has redefined the term "[[archosaur]]" to only include bird-line archosaurs ([[Avemetatarsalia]]) and crocodile-line archosaurs ([[Pseudosuchia]]). As proterosuchids evolved prior to the split between these two groups, they are not considered archosurs using this definition. In lieu of this revelation, the clade Archosauriformes is now used to encompass proterosuchids and archosaurs (as well as several other [[Family (biology)|families]]) under one group. |

||

During this transition, ''Tasmaniosaurus'' remained ignored. This was rectified when the genus received a thorough redescription by Ezcurra in 2014.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Ezcurra|first=Martín D.|date=2014-01-30|title=The Osteology of the Basal Archosauromorph Tasmaniosaurus triassicus from the Lower Triassic of Tasmania, Australia|url=http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0086864|journal=PLOS ONE|language=en|volume=9|issue=1|pages=e86864|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0086864|issn=1932-6203}}</ref> In 2016, Ezcurra also included the genus in his comprehensive analysis of Archosauromorphs, which indicated that proterosuchidae (as it was usually defined) was an invalid [[Polyphyly|polyphyletic]] grouping. This analysis included a [[Phylogenetics|phylogenetic analysis]] which incorporated ''Tasmaniosaurus'' and found that it was not in fact a proterosuchid. Rather, it was found to be the [[sister taxon]] of Archosauriformes, meaning that it was the closest known relative of members of that clade without technically being part of it (as it was not closer to either proterosuchids or other archosauriforms).<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Ezcurra|first=Martín D.|date=2016-04-28|title=The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms|url=https://peerj.com/articles/1778/|journal=PeerJ|language=en|volume=4|doi=10.7717/peerj.1778|issn=2167-8359}}</ref> |

During this transition, ''Tasmaniosaurus'' remained ignored. This was rectified when the genus received a thorough redescription by Ezcurra in 2014.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Ezcurra|first=Martín D.|date=2014-01-30|title=The Osteology of the Basal Archosauromorph Tasmaniosaurus triassicus from the Lower Triassic of Tasmania, Australia|url=http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0086864|journal=PLOS ONE|language=en|volume=9|issue=1|pages=e86864|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0086864|issn=1932-6203}}</ref> In 2016, Ezcurra also included the genus in his comprehensive analysis of Archosauromorphs, which indicated that proterosuchidae (as it was usually defined) was an invalid [[Polyphyly|polyphyletic]] grouping. This analysis included a [[Phylogenetics|phylogenetic analysis]] which incorporated ''Tasmaniosaurus'' and found that it was not in fact a proterosuchid. Rather, it was found to be the [[sister taxon]] of Archosauriformes, meaning that it was the closest known relative of members of that clade without technically being part of it (as it was not closer to either proterosuchids or other archosauriforms).<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Ezcurra|first=Martín D.|date=2016-04-28|title=The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms|url=https://peerj.com/articles/1778/|journal=PeerJ|language=en|volume=4|doi=10.7717/peerj.1778|issn=2167-8359}}</ref> |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

== Description == |

== Description == |

||

[[File:Tasmaniosaurus triassicus.png|thumb|left|Blocks of the type specimen]] |

[[File:Tasmaniosaurus triassicus.png|thumb|left|Blocks of the type specimen]] |

||

''Tasmaniosaurus'' is known from a single partial skeleton, UTGD ([[University of Tasmania]] School of Earth Sciences) 54655. This holotype specimen consists of various skull fragments, vertebrae, ribs, and limb bones. It is considered one of the most complete skeletons of any Triassic reptile unearthed in Australia. A few other bone fragments collected around Tasmania have been occasionally referred to this genus, but they are currently considered indeterminate and lost.<ref name=":0" /> |

''Tasmaniosaurus'' is known from a single partial skeleton, UTGD ([[University of Tasmania]] School of Earth Sciences) 54655. This holotype specimen consists of various skull fragments, vertebrae, ribs, an interclavicle, and limb bones. It is considered one of the most complete skeletons of any Triassic reptile unearthed in Australia. A few other bone fragments collected around Tasmania have been occasionally referred to this genus, but they are currently considered indeterminate and lost.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

=== Skull and teeth === |

=== Skull and teeth === |

||

==== Snout bones ==== |

|||

The premaxilla (a tooth-bearing bone forming the snout tip) was initially mistaken to be very short due to crushing. However, it was later found to be proportionally similar to that of most archosauriforms. It is rounded from the front and possesses a long and tall 'maxillary process' (rear extension). By comparing the orientation of this process with the tooth row, the snout tip was determined to be only slightly projected downwards, in contrast to the drastically hooked snout of putative proterosuchids. Although only a few teeth are preserved in the right premaxilla, a count of the tooth sockets helps estimates that 6 or 7 teeth were present in each premaxilla during life.<ref name=":1" /> |

The premaxilla (a tooth-bearing bone forming the snout tip) was initially mistaken to be very short due to crushing. However, it was later found to be proportionally similar to that of most archosauriforms. It is rounded from the front and possesses a long and tall 'maxillary process' (rear extension). By comparing the orientation of this process with the tooth row, the snout tip was determined to be only slightly projected downwards, in contrast to the drastically hooked snout of putative proterosuchids. Although only a few teeth are preserved in the right premaxilla, a count of the tooth sockets helps estimates that 6 or 7 teeth were present in each premaxilla during life.<ref name=":1" /> |

||

The maxilla (a tooth-bearing bone on the side of the snout) has a long tooth row and a tapering rear tip. The front tip also forms a tapering 'anterior process' which smoothly transitions into a triangular and upward-projecting 'ascending process'. This contrasts with proterosuchids, which have a less abruptly tapering anterior process, and [[Erythrosuchidae|erythrosuchids]], which have a pillar-like ascending process. The shape of the upper edge of the maxilla indicates that ''Tasmaniosaurus'' had an [[antorbital fenestra]], a hole in the side of the snout which seemingly characterizes archosauriforms. The presence of an antorbital fenestra supports the very close relation between ''Tasmaniosaurus'' and archosauriforms. As the skull bones are all preserved lying face down, it is difficult to assess whether an antorbital fossa (a depression which rings around the antorbital fenestra) was also present. The left maxilla preserves 14 teeth while the right preserves 9. An estimated 21 teeth were present in each maxilla during life.The lacrimal bone (in front of the orbit, or eye hole) is L-shaped and particularly similar to that of ''[[Proterosuchus]]''. On the medial (inside) face, a large tuberosity (bony bump) is present where the forward and downward extensions meet.<ref name=":1" /> |

The maxilla (a tooth-bearing bone on the side of the snout) has a long tooth row and a tapering rear tip. The front tip also forms a tapering 'anterior process' which smoothly transitions into a triangular and upward-projecting 'ascending process'. This contrasts with proterosuchids, which have a less abruptly tapering anterior process, and [[Erythrosuchidae|erythrosuchids]], which have a pillar-like ascending process. The shape of the upper edge of the maxilla indicates that ''Tasmaniosaurus'' had an [[antorbital fenestra]], a hole in the side of the snout which seemingly characterizes archosauriforms. The presence of an antorbital fenestra supports the very close relation between ''Tasmaniosaurus'' and archosauriforms. As the skull bones are all preserved lying face down, it is difficult to assess whether an antorbital fossa (a depression which rings around the antorbital fenestra) was also present. The left maxilla preserves 14 teeth while the right preserves 9. An estimated 21 teeth were present in each maxilla during life.The lacrimal bone (in front of the orbit, or eye hole) is L-shaped and particularly similar to that of ''[[Proterosuchus]]''. On the medial (inside) face, a large tuberosity (bony bump) is present where the forward and downward extensions meet. A partial [[Pterygoid bone|pterygoid]] bone (a tooth-bearing part of the roof of the mouth) is preserved in the specimen, and is almost identical to that of ''Proterosuchus'' and ''[[Prolacerta]]''. It preserves six or seven teeth, and likely represents the front part of the pterygoid.<ref name=":1" /> |

||

==== Skull roof ==== |

|||

| ⚫ | Several bones of the skull roof were also preserved connected to each other in the holotype. Camp & Banks considered these to be [[Frontal bone|frontals]], [[Parietal bone|parietals]], an [[Interparietal bone|interparietal]], and postfrontals, all bones of the rear of the skull. Thulborn instead interpreted them as frontals, [[Nasal bone|nasals]], and [[Postorbital bone|postorbitals]], on the upper side of the snout. Most recently, Ezcurra discussed both of these interpretations and concluded that Camp & Banks were correct in their identification of the bones. The frontals are long and unfused, and possess thin "finger-like" extensions which would have connected to the nasals. Each postfrontal, which formed the upper rear edge of the orbit, is similar to that of ''[[Archosaurus]]'' but the extent of its contact with the other bones is unclear. The parietals are unfused and have wide and concave outer edges, forming the inner edge of the upper temporal fenestrae (a pair of large holes on each side of the back of the head). The back of each parietal has a long bony rod which extends backwards and curves outwards (a posterolateral process), forming an angle of about 20 degrees with the midline of the skull. A large crescent shape interparietal lies at the back of the skull roof, between the posterolateral processes of the parietals, similar to [[Proterosuchidae|proterosuchids]]. Two smaller bone fragments were also found near the skull roof and may have been a supraoccipital and epipterygoid (both bones of the braincase), although such an assignment is uncertain.<ref name=":1" /> |

||

==== Lower jaw ==== |

|||

The dentaries (the main tooth-bearing bones of the lower jaw) are long, thin, and straight, similar to those of ''Prolacerta'' and ''[[Protorosaurus]]'' but contrasting with the robust and/or upwards-curving jaws of most basal archosauriforms. In fact, the tooth row at the very tip of the jaw slightly curves downward, forcing the first few teeth to project a bit forwards as well as upwards. The rear edge of each dentary has two tapering bony extensions, a short (but partially broken) 'posterodorsal process' on top and a much more prominent 'central posterior process' on the bottom. The dentaries are long enough that the front tip extends almost as far forward as the snout tip while the tooth row would extend almost as far back as the tooth row of the maxilla, both features unlike ''Prolacerta'' and ''Proterosuchus''. Only 5 teeth are preserved in the left dentary, but more than 22 were likely present in life. A thick left splenial (a bone of the inside and lower edge of the lower jaw), similar to that of ''Proterosuchus'', is also preserved.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

==== Teeth ==== |

|||

The teeth of ''Tasmaniosaurus'' are ankylothecodont, meaning that they are both fused to the skull and jaw bones by thin ridges (ankylodont) as well as placed in deep sockets ([[Thecodont dentition|thecodont]]). They are also serrated, similar to those of archosauriforms but unlike practically every other archosauromorph. Although not all of the teeth are preserved in good condition, those that are have a curved shape and are compressed from the side, making them knife-like, similar to most carnivorous archosauromorphs.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

=== Spine and ribs === |

|||

==== Back and neck vertebrae ==== |

|||

The ''Tasmaniosaurus'' holotype preserves 2 presacral (pre-hip) [[Vertebra|vertebrae]], one probably from near the transition between the neck and back and the other probably from mid-way down the back. The cervico-dorsal (neck-back) vertebra is slightly compressed with a shallow depression each side, and does not possess an opening for the spinal cord. Both the neural arch (are normally above the spinal cord) and neural spine (plate-like extension on the top of the vertebra) are tall. The second preserved vertebra, a dorsal, is incomplete but similar to the cervico-dorsal. A curving table-like ridge (lamina) on the side of the vertebra extends forward (as a 'prezygodiapophyseal lamina') and then dips downwards (as a 'paradiapophyseal lamina') towards the front of the vertebra. Various other archosauromorphs also have prezygodiapophyseal laminae, but they are notably lacking in ''Proterosuchus''. On the other hand, the tip of the neural spine does not expand outwards in this vertebra, similar to the condition in ''Proterosuchus''. A few putative intercentra (small bones wedged between the lower part of the vertebrae) have also been reported in ''Tasmaniosaurus''.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

==== Ribs ==== |

|||

| ⚫ | Several bones of the skull roof were also preserved in the holotype. Camp & Banks considered these to be [[Frontal bone|frontals]], [[Parietal bone|parietals]], an [[Interparietal bone|interparietal]], and postfrontals, all bones of the rear of the skull. Thulborn instead interpreted them as frontals, [[Nasal bone|nasals]], and [[Postorbital bone|postorbitals]], on the upper side of the snout. Most recently, Ezcurra discussed both of these interpretations and concluded that Camp & Banks were correct in their identification of the bones. The frontals are long and unfused, and possess thin "finger-like" extensions which would have connected to the nasals. Each postfrontal, which formed the upper rear edge of the orbit, is similar to that of ''[[Archosaurus]]'' but the extent of its contact with the other bones is unclear. The parietals are unfused and have wide and concave outer edges, forming the inner edge of the upper temporal fenestrae (a pair of large holes on each side of the back of the head). The back of each parietal has a long bony rod which extends backwards and curves outwards (a posterolateral process), forming an angle of about 20 degrees with the midline of the skull. A large crescent shape interparietal lies at the back of the skull roof, between the posterolateral processes of the parietals, similar to [[Proterosuchidae|proterosuchids]].<ref name=":1" /> |

||

''Tasmaniosaurus'' was about 1 metre long, and similar in appearance to the [[proterosuchid]] ''[[Chasmatosaurus]]'' from Africa and China, which may be its closest relative.<ref name="TRA79">{{cite journal |last=Thulborn |first=R. A. |year=1979 |title=A proterosuchian thecodont from the Rewan Formation of Queensland |journal=Memoirs of the Queensland Museum |volume=19 |pages=331–355}}</ref> It is however distinguished from other proterosuchids by the presence of an interclavicle, which other members had lost. The premaxilla is slightly curved. The teeth are sharp. It may have fed, amongst other creatures, on [[labyrinthodonts]], as remains of these amphibians are associated with the skeleton. It is surmised that many proterosuchids lived an amphibious, predatory life like crocodiles today. ''Tasmaniosaurus'' had no dermal [[scutes]]. ''Tasmaniosaurus'' is one of the earliest reptiles known to have lived in Australia. Another proterosuchid, ''[[Kalisuchus]] rewanensis'', is known from the Early Triassic of Queensland, Australia. |

''Tasmaniosaurus'' was about 1 metre long, and similar in appearance to the [[proterosuchid]] ''[[Chasmatosaurus]]'' from Africa and China, which may be its closest relative.<ref name="TRA79">{{cite journal |last=Thulborn |first=R. A. |year=1979 |title=A proterosuchian thecodont from the Rewan Formation of Queensland |journal=Memoirs of the Queensland Museum |volume=19 |pages=331–355}}</ref> It is however distinguished from other proterosuchids by the presence of an interclavicle, which other members had lost. The premaxilla is slightly curved. The teeth are sharp. It may have fed, amongst other creatures, on [[labyrinthodonts]], as remains of these amphibians are associated with the skeleton. It is surmised that many proterosuchids lived an amphibious, predatory life like crocodiles today. ''Tasmaniosaurus'' had no dermal [[scutes]]. ''Tasmaniosaurus'' is one of the earliest reptiles known to have lived in Australia. Another proterosuchid, ''[[Kalisuchus]] rewanensis'', is known from the Early Triassic of Queensland, Australia. |

||

Revision as of 02:30, 24 February 2018

| Tasmaniosaurus Temporal range: Early Triassic,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Restored skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauromorpha |

| Clade: | Crocopoda |

| Genus: | †Tasmaniosaurus Camp & Banks, 1978 |

| Type species | |

| †Tasmaniosaurus triassicus Camp & Banks, 1978

| |

Tasmaniosaurus ('Lizard from Tasmania', although this genus is not a true lizard) is an extinct genus of archosauromorph reptile known from the Knocklofty Formation (Early Triassic) of West Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. The type species is T. triassicus. This genus is notable not only due to being one of the most complete Australian Triassic reptiles known, but also due to being a very close relative of Archosauriformes. Once believed to be a proterosuchid, this taxon is now believed to have been intermediate between advanced non-archosauriform archosauromorphs such as Prolacerta, and basal archosauriforms such as Proterosuchus. Features traditionally used to define Archosauria and later Archosauriformes, such as the presence of an antorbital fenestra and serrated teeth, are now known to have evolved prior to those groups due to their presence in Tasmaniosaurus.[1]

History and Classification

First named as a nomen nudum in 1974, the genus received a formal description by Camp & Banks in 1978.[2][3]These descriptions considered it a proterosuchid archosaur. A rediscription by Thulborn in 1986 agreed with this interpretation.[4] Since then, cladistic work has redefined the term "archosaur" to only include bird-line archosaurs (Avemetatarsalia) and crocodile-line archosaurs (Pseudosuchia). As proterosuchids evolved prior to the split between these two groups, they are not considered archosurs using this definition. In lieu of this revelation, the clade Archosauriformes is now used to encompass proterosuchids and archosaurs (as well as several other families) under one group.

During this transition, Tasmaniosaurus remained ignored. This was rectified when the genus received a thorough redescription by Ezcurra in 2014.[5] In 2016, Ezcurra also included the genus in his comprehensive analysis of Archosauromorphs, which indicated that proterosuchidae (as it was usually defined) was an invalid polyphyletic grouping. This analysis included a phylogenetic analysis which incorporated Tasmaniosaurus and found that it was not in fact a proterosuchid. Rather, it was found to be the sister taxon of Archosauriformes, meaning that it was the closest known relative of members of that clade without technically being part of it (as it was not closer to either proterosuchids or other archosauriforms).[1]

Description

Tasmaniosaurus is known from a single partial skeleton, UTGD (University of Tasmania School of Earth Sciences) 54655. This holotype specimen consists of various skull fragments, vertebrae, ribs, an interclavicle, and limb bones. It is considered one of the most complete skeletons of any Triassic reptile unearthed in Australia. A few other bone fragments collected around Tasmania have been occasionally referred to this genus, but they are currently considered indeterminate and lost.[1]

Skull and teeth

Snout bones

The premaxilla (a tooth-bearing bone forming the snout tip) was initially mistaken to be very short due to crushing. However, it was later found to be proportionally similar to that of most archosauriforms. It is rounded from the front and possesses a long and tall 'maxillary process' (rear extension). By comparing the orientation of this process with the tooth row, the snout tip was determined to be only slightly projected downwards, in contrast to the drastically hooked snout of putative proterosuchids. Although only a few teeth are preserved in the right premaxilla, a count of the tooth sockets helps estimates that 6 or 7 teeth were present in each premaxilla during life.[5]

The maxilla (a tooth-bearing bone on the side of the snout) has a long tooth row and a tapering rear tip. The front tip also forms a tapering 'anterior process' which smoothly transitions into a triangular and upward-projecting 'ascending process'. This contrasts with proterosuchids, which have a less abruptly tapering anterior process, and erythrosuchids, which have a pillar-like ascending process. The shape of the upper edge of the maxilla indicates that Tasmaniosaurus had an antorbital fenestra, a hole in the side of the snout which seemingly characterizes archosauriforms. The presence of an antorbital fenestra supports the very close relation between Tasmaniosaurus and archosauriforms. As the skull bones are all preserved lying face down, it is difficult to assess whether an antorbital fossa (a depression which rings around the antorbital fenestra) was also present. The left maxilla preserves 14 teeth while the right preserves 9. An estimated 21 teeth were present in each maxilla during life.The lacrimal bone (in front of the orbit, or eye hole) is L-shaped and particularly similar to that of Proterosuchus. On the medial (inside) face, a large tuberosity (bony bump) is present where the forward and downward extensions meet. A partial pterygoid bone (a tooth-bearing part of the roof of the mouth) is preserved in the specimen, and is almost identical to that of Proterosuchus and Prolacerta. It preserves six or seven teeth, and likely represents the front part of the pterygoid.[5]

Skull roof

Several bones of the skull roof were also preserved connected to each other in the holotype. Camp & Banks considered these to be frontals, parietals, an interparietal, and postfrontals, all bones of the rear of the skull. Thulborn instead interpreted them as frontals, nasals, and postorbitals, on the upper side of the snout. Most recently, Ezcurra discussed both of these interpretations and concluded that Camp & Banks were correct in their identification of the bones. The frontals are long and unfused, and possess thin "finger-like" extensions which would have connected to the nasals. Each postfrontal, which formed the upper rear edge of the orbit, is similar to that of Archosaurus but the extent of its contact with the other bones is unclear. The parietals are unfused and have wide and concave outer edges, forming the inner edge of the upper temporal fenestrae (a pair of large holes on each side of the back of the head). The back of each parietal has a long bony rod which extends backwards and curves outwards (a posterolateral process), forming an angle of about 20 degrees with the midline of the skull. A large crescent shape interparietal lies at the back of the skull roof, between the posterolateral processes of the parietals, similar to proterosuchids. Two smaller bone fragments were also found near the skull roof and may have been a supraoccipital and epipterygoid (both bones of the braincase), although such an assignment is uncertain.[5]

Lower jaw

The dentaries (the main tooth-bearing bones of the lower jaw) are long, thin, and straight, similar to those of Prolacerta and Protorosaurus but contrasting with the robust and/or upwards-curving jaws of most basal archosauriforms. In fact, the tooth row at the very tip of the jaw slightly curves downward, forcing the first few teeth to project a bit forwards as well as upwards. The rear edge of each dentary has two tapering bony extensions, a short (but partially broken) 'posterodorsal process' on top and a much more prominent 'central posterior process' on the bottom. The dentaries are long enough that the front tip extends almost as far forward as the snout tip while the tooth row would extend almost as far back as the tooth row of the maxilla, both features unlike Prolacerta and Proterosuchus. Only 5 teeth are preserved in the left dentary, but more than 22 were likely present in life. A thick left splenial (a bone of the inside and lower edge of the lower jaw), similar to that of Proterosuchus, is also preserved.[5]

Teeth

The teeth of Tasmaniosaurus are ankylothecodont, meaning that they are both fused to the skull and jaw bones by thin ridges (ankylodont) as well as placed in deep sockets (thecodont). They are also serrated, similar to those of archosauriforms but unlike practically every other archosauromorph. Although not all of the teeth are preserved in good condition, those that are have a curved shape and are compressed from the side, making them knife-like, similar to most carnivorous archosauromorphs.[5]

Spine and ribs

Back and neck vertebrae

The Tasmaniosaurus holotype preserves 2 presacral (pre-hip) vertebrae, one probably from near the transition between the neck and back and the other probably from mid-way down the back. The cervico-dorsal (neck-back) vertebra is slightly compressed with a shallow depression each side, and does not possess an opening for the spinal cord. Both the neural arch (are normally above the spinal cord) and neural spine (plate-like extension on the top of the vertebra) are tall. The second preserved vertebra, a dorsal, is incomplete but similar to the cervico-dorsal. A curving table-like ridge (lamina) on the side of the vertebra extends forward (as a 'prezygodiapophyseal lamina') and then dips downwards (as a 'paradiapophyseal lamina') towards the front of the vertebra. Various other archosauromorphs also have prezygodiapophyseal laminae, but they are notably lacking in Proterosuchus. On the other hand, the tip of the neural spine does not expand outwards in this vertebra, similar to the condition in Proterosuchus. A few putative intercentra (small bones wedged between the lower part of the vertebrae) have also been reported in Tasmaniosaurus.[5]

Ribs

Tasmaniosaurus was about 1 metre long, and similar in appearance to the proterosuchid Chasmatosaurus from Africa and China, which may be its closest relative.[6] It is however distinguished from other proterosuchids by the presence of an interclavicle, which other members had lost. The premaxilla is slightly curved. The teeth are sharp. It may have fed, amongst other creatures, on labyrinthodonts, as remains of these amphibians are associated with the skeleton. It is surmised that many proterosuchids lived an amphibious, predatory life like crocodiles today. Tasmaniosaurus had no dermal scutes. Tasmaniosaurus is one of the earliest reptiles known to have lived in Australia. Another proterosuchid, Kalisuchus rewanensis, is known from the Early Triassic of Queensland, Australia.

References

- ^ a b c Ezcurra, Martín D. (2016-04-28). "The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms". PeerJ. 4. doi:10.7717/peerj.1778. ISSN 2167-8359.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Camp, C. L.; Banks, M. R. (1978). "A proterosuchian reptile from the Early Triassic of Tasmania". Alcheringa. 2: 143–158. doi:10.1080/03115517808619085.

- ^ Cosgriff, J. W. (1974). "Lower Triassic Temnospondyli of Tasmania". Special Papers of the Geological Society of America. 149: 1–134. doi:10.1130/spe149-p1.

- ^ Thulborn, R. A. (1986). "The Australian Triassic reptile Tasmaniosaurus triassicus (Thecodontia: Proterosuchia)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 6 (2): 123–142. doi:10.1080/02724634.1986.10011606.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ezcurra, Martín D. (2014-01-30). "The Osteology of the Basal Archosauromorph Tasmaniosaurus triassicus from the Lower Triassic of Tasmania, Australia". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e86864. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086864. ISSN 1932-6203.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Thulborn, R. A. (1979). "A proterosuchian thecodont from the Rewan Formation of Queensland". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 19: 331–355.