Tanystropheus

| Tanystropheus | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

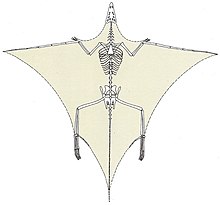

Skeletal reconstruction of a large specimen of Tanystropheus in the Paleontological Museum in Zurich . Due to the perspective, the neck looks significantly longer in relation to the rest of the body than it is anyway. |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Central to Upper Triassic | ||||||||||||

| 247.2 to 208.5 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Tanystropheus | ||||||||||||

| von Meyer , 1852 | ||||||||||||

Tanystropheus ( Syn .: Tribelesodon , trivially also "Giraffe- necked dinosaur") is a genus "primitive" but morphologically very peculiar genus of Archosauromorpha from the middle and upper Triassic Eurasia. Their strongly elongated neck with an overall quite graceful physique is typical. With its extreme proportions, Tanystropheus is considered a "biomechanical and palecological puzzle".

etymology

The name of the genus was created by Hermann von Meyer in 1852 coined . It is ancient Greek and means of the male suffix -εύς -eus from the compound from the prefix τανύ- tany- , long (stretched) 'and the noun στρόφος strophos , strand, tape, cord, belt' derived . It therefore means something like 'the long-bodied' or 'the long-stranded', which probably refers to the extraordinary length of the vertebrae and the section of the spine formed by them. However, von Meyer did not know at the time that the 'long strand' was around the neck (see finds and taxonomic history ).

features

The most distinctive feature of Tanystropheus is the greatly elongated neck, which in the individuals of T. hydroides was at least as long as the trunk and tail together. However, it contained only 12 or 13 amphicoele vertebrae, most of which, however, are extremely long. Presumably because of their length, because they are hollow and because of the wing-like protruding zygapophyses at their ends, which in the back (dorsal) and abdominal (ventral) view are reminiscent of the epiphyses of long bones , the first cervical vertebrae found were thought to be extremity bones . In fact, the longest cervical vertebrae in Tanystropheus are roughly the same length as the slightly S-shaped curved femur. In largely completely preserved specimens, the posterior zygapophyses (postzygapophyses) joint from "above" (dorsal) with the anterior zygapophyses (prezygapophyses) of the subsequent vertebra. The plane of this joint is relatively steeply inclined to the horizontal. The neural arches are largely reduced and the spinal canal runs within the vertebral bodies (centra). Only at the anterior and posterior ends of the vertebrae are small, low spinous processes on the back, which suggests that the neck muscles were not particularly strong and limited to the intervertebral muscles. Each cervical vertebra is articulated at its front end on the ventral side (ventrally) with a pair of long, single-headed (monocotyledonous), rod-like ribs that are parallel to the cervical spine. The trunk and tail vertebrae are "normal" and not elongated.

Due to the small number of vertebrae and the stiffening long ribs, the neck was probably not too flexible. The relatively steep articular surfaces of the zygapophyses must have ensured that it was more flexible in the vertical plane than in the horizontal plane. If the skull and cervical skeleton were light enough, Tanystropheus could have lifted his head a long way above the torso despite the weak neck muscles.

Tanystropheus reached a total body length of three to at least five meters. The "catapsid" windowed skull (lower temporal arch reduced) is very small in relation to the rest of the skeleton. The jawbones are equipped with numerous pointed conical (the maxillary in T. longobardicus with three-pointed) teeth, which interlocked with the mouth closed. Depending on the type, one or more bones of the roof of the mouth are covered with small, pointed teeth (vomer, palatine) or denticles ( pterygoid ). The forelimbs are comparatively short and “minimally” ossified in the area of the wrist. The rear extremities are about 1.7 times as long as the front and have a well ossified tarsus with a normal astragalus-calcaneus complex.

Way of life

Regarding the way of life of Tanystropheus and the function of the long, not very flexible neck, there is still disagreement. It is relatively certain that Tanystropheus had a close relationship with the sea, as its fossil remains were only found in marine sedimentary rocks . The hard parts of probable prey found in the presumed epigastric region of Tanystropheus skeletons, including fish scales and tentacle hooks (onychites) of belemnites , also suggest such a relationship . How strong the connection to the water as a habitat was is, however, controversial and depends directly on the interpretation of the bone structure. Processors who consider the neck of Tanystropheus to be extremely rigid and the rest of the body to be relatively well adapted to swimming locomotion favor an aquatic way of life, whereby the propulsion in the water is mainly subordinate to the snaking movements (lateral undulation) of the trunk and tail , is said to have been produced by paddling with the hind legs. Other authors suspect a moderate flexibility of the neck and see in fact no adaptation of the extremities or the tail skeleton to swimming movement. Indirect fossil evidence for the presence of a large, heavy muscle mass at the base of the tail (see Finds and Taxonomic History ) would offer a solution to the biomechanical problem of head load that inevitably occurs on land in an animal with such an extremely long neck when the head is raised. Tanystropheus could have been a stalker who z. B. on a rock on the coast, with dry feet or in very shallow water with the head held high on the lookout for swimming prey.

Small individuals traditionally interpreted as young animals of the species T. longobardicus had a significantly shorter neck compared to the rest of the body and three-pointed teeth ( eponymous for the synonym Tribelesodon ) on the maxillary and in the back of the dentary. Since fish-eaters usually have pointed conical teeth, it has been suggested that these individuals lived a less marine-related way of life and ate insects. A more recent alternative hypothesis sees the three-pointed teeth as an analogue to the multi-pointed teeth of some dog seal species and therefore postulates an aquatic way of life for these small representatives as well. Due to the differences in the dentition and also in the structure of various bones as well as on the basis of the results of morphometric investigations, it was considered that the small individuals could represent a different species than the large individuals known from the Alpine Upper Triassic, which is finally taxonomically reflected in the first description of T .hydides precipitated for the large specimens.

Finds and taxonomic history

During his private excavations in the Upper Muschelkalk of Bayreuth in the 1830s, Georg Graf zu Münster found hollow, rod-shaped bones that reached a length of almost 30 centimeters. These were identified by Hermann von Meyer as the caudal vertebrae of "Macrotrachelen", reptiles closely related to Nothosaurus , and described in 1852 * under the name Tanystropheus conspicuus . In 1896 Eberhard Fraas mentioned isolated teeth and bones from the Muschelkalk-Keuper-Grenz bonebed from Crailsheim , which he described under the name " Nothosaurus blezingeri ". According to Olivier Rieppel (1996), at least the teeth contained in this material belong to Tanystropheus . Around the middle of the first decade of the 20th century, Friedrich von Huene described elongated vertebral bones from the southern German, Lorraine and Upper Silesian Muschelkalk, on which he based the new species Thecodontosaurus latespinatus and Tanystrophaeus (sic!) Antiquus . Von Huene also interpreted these fossils as caudal vertebrae, but assigned them to early theropods from the closer relationship of Coelophysis . While “ Thecodontosaurus latespinatus ” was later synonymous with Tanystropheus conspicuus , Tanystropheus antiquus is in its own genus, Protanystropheus , due to its relatively strongly deviating structure of the cervical spine (fewer and more massive vertebrae) ** and its higher geological age (lower instead of upper shell limestone) been. Von Huene was not the only one who “mixed” Tanystropheus and early theropods. In a work from 1887 had the famous American paleontologist Edward D. Cope material under the names " Tanystrophaeus willi toni ", " Tanystrophaeus " bauri and " Tanystrophaeus longicollis " described that today, one and all under the name Coelophysis bauri run .

During and long after the establishment of the genus by von Meyer, the actual body structure of these animals was therefore unknown and their fossil remains were repeatedly misinterpreted or not even recognized. It was not until September 1929 that a working group led by the Zurich paleontologist Bernhard Peyer was able to recover an almost complete skeleton for the first time in the bitumen slates ("scisti bituminosi", "border bitumen zone") of Monte San Giorgio in Ticino after a blast in an opencast mine. It was in this Fund for a copy of the 1886 by Italian Francesco Bassani using a poorly preserved skeleton from around Besano , near the Monte San Giorgio, described and as pterosaurs interpreted Art Tribelesodon longobardicus . Their affiliation to the genus Tanystropheus thus became clear. On the one hand, the elongated vertebrae could now be correctly recognized as cervical vertebrae *** and on the other hand it became obvious that Tanystropheus was not a very close relative of Nothosaurus and certainly not a dinosaur, but belonged to a different group of Mesozoic reptiles, the Peyer "Tanysitrachelia" called and subordinated the Sauropterygia .

In 1975, the Hungaro-Romanian paleontologist Tibor Jurcsák described the species Tanystropheus bihoricus based on cervical vertebrae made from Central Triassic limestones from the Bihor region in the Carpathian Mountains of northwestern Romania . This species was first put synonymously with Tanystropheus longobardicus by Rupert Wild in 1980 . In the same year, Wild, who had already reworked T. longobardicus in the early 1970s , described two new Tanystropheus species, T. meridensis and T. fossai , from the Meride limestone of Monte San Giorgio and Riva on the basis of relatively incomplete specimens -di-Solto-claystone (Argillite di Riva di Solto) of Friuli (Northeast Italy). But the validity of these two types, too, has subsequently been questioned. Thus T. meridensis as a synonym of T. longobardicus classified and T. fossai even doubts that it is a member of the genus Tanystropheus concerns. Wild was also the one who established generic name Tanystropheus by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) for Protectum noun could be explained after the allegedly dominated by Munster name Macroscelosaurus of Oskar Kuhn in several works as an older and therefore priority synonymous Tanystropheus been used was. In unity with the protection of the name Tanystropheus , the name Macroscelosaurus was declared a noun suppressum by the ICZN . Furthermore, Wild Peyers rejected Tanysitrachelia and classified Tanystropheus with the Prolacertiformes, which at the time were considered to be the “parent group” of Lacertilia .

The first remains of Tanystropheus outside of Europe came to light in the 1950s when they were collected in the “shell limestone” of Makesh Ramon in the Negev desert in Israel. The discoverer was the Austrian-Israeli zoologist Georg Haas , who reported the finds to Peyer and some of them passed on to Zurich. Olivier Rieppel described the new species Tanystropheus haasi in 2001 on the basis of several incomplete cervical vertebrae that were found there during later excursions . In 2005, the Italian paleontologist Silvio Renesto published the description of a new find , identified as Tanystropheus cf. longobardicus , of a skeleton from the Meride limestone of Monte San Giorgio, in whose “loin” region clearly visible imprints of the skin with square scales are preserved. In addition, carbonate-phosphatic tubers in the proximal tail region of this specimen provide indirect evidence that an unusually large muscle mass could have been found there during its lifetime and at the beginning of the decomposition of the carcass. Two years later a monograph by the Italian Stefania Nosotti appeared, in which she made new discoveries by u. a. describes in detail largely complete skeletons of two individuals of Tanystropheus longobardicus from the vicinity of Besano.

In the same year, the second evidence of Tanystropheus outside of Europe was reported. It is an incomplete but anatomically transmitted skeleton of a juvenile individual from the Central / Upper Triassic border area of the carbonate Falang Formation of Guizhou Province (S-China). A second specimen from the region was found in 2006 and published in 2010. This relatively large specimen, classified as Tanystropheus cf. longobardicus , comes from a somewhat more recent interval of the same formation and consists of a trunk skeleton including the proximal parts of the cervical and caudal spine. It confirms that Tanystropheus in the later Triassic was evidently not restricted to the western part of Laurasia .

In 2015, Hans-Dieter Sues and Paul E. Olsen made a single, 76 millimeter long, incomplete but diagnostic anterior or middle cervical vertebra from the? Middle Triassic economy formation as the "first evidence of a long-necked Tanystropheid in North America" under the name cf. Tanystropheus sp. depicted in a paper on the vertebrate fossil societies of the Fundy Basin (Nova Scotia, Eastern Canada). However, as early as 1988, Olsen listed the genus rather casually in a synopsis of the fossil faunas of the entire Newark supergroup , and in 1993 a "single, diagnostic [vertebral] center" was mentioned in the literature.

In August 2020, Stephan Spiekman and colleagues will publish the first description of the species Tanystropheus hydroides from the border bitumen zone of Monte San Giorgio. The new species includes specimens that were previously considered fully-grown individuals of T. longobardicus . More detailed investigations of the material, in particular with the aid of computer tomography- based three-dimensional skull reconstructions, however, showed clear differences between the skull proportions and the teeth of large and small specimens (including a flatter snout and very long fangs in the front part of the snout in the former). Above all, however, bone histological examinations could show that the small specimens were not juveniles, but fully grown. This ultimately justified the creation of a separate species for the large specimens.

Systematics

External system

Tanystropheus is the type genus of the family Tanystropheidae , which includes other, very similar forms and is restricted to the Triassic . The North American genus Tanytrachelos is considered relatively closely related to Tanystropheus . A somewhat more distant relative is the Chinese genus Dinocephalosaurus , which shows significantly stronger adaptations to an aquatic way of life than Tanystropheus .

The Tanystropheids, in turn, belong to a peculiar Permo-Triassic line of the stem group archosaurs (basal Archosauromorpha ), which is known under the name Protorosauria or Prolacertilia. As members of the bird-crocodile line, the long-necked Tanystropheids, contrary to what many paleontologists assumed in the 20th century, are neither closely related to the long-necked Mesozoic marine reptiles, which are united in the group Sauropterygia , nor as members of the snake "lizards "-Line ( Lepidosauromorpha ) apply, still in close relation to the" lizards "(Lacertilia) themselves.

Internal system

To date, a number of are Tanystropheus - types described or mentioned in the literature (see discoveries and taxonomic history ), of which in addition to the type species, but only three currently (as of 2020) widely recognized and this genus are actually attributable to:

- Tanystropheus conspicuus von Meyer , 1852 - Central Triassic - Southern Germany, Lorraine (France); Type-Art

- Tanystropheus longobardicus ( Bassani , 1886) - Upper Triassic - Ticino (Switzerland), Varese (NW-Italy), Bihor (NW-Romania) [ Guizhou (S-China)]

- Tanystropheus hydroides Spiekmann et al., 2020 (formerly the large morphotype of T. longobardicus ) - Upper Triassic - Ticino (Switzerland), Varese (NW-Italy)

- Tanystropheus haasi Rieppel , 2001 - Middle Triassic - Israel

T. longobardicus and T. hydroides are the best known species. They are by far the greatest and most complete material, and much of what is known about the genus has been obtained from studying specimens of these two species.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Rupert Wild: The giraffe neck dinosaur. In: The natural sciences. Vol. 62, No. 4, 1975, pp. 149-153, doi: 10.1007 / BF00608696 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Silvio Renesto: A new specimen of Tanystropheus (Reptilia Protorosauria) from the Middle Triassic of Switzerland and the ecology of the genus. In: Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia. Vol. 111, No. 3, 2005, pp. 377-394, ( PDF 2.29 MB); see also literature cited therein.

- ↑ a b c d Hermann von Meyer: To the fauna of the pre-world. The muschelkalk dinosaurs with regard to the dinosaurs made of colored sandstone and keuper. Verlag von Heinrich Keller, Frankfurt am Main 1847–1855, doi: 10.3931 / e-rara-43030 , p. 41 f.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Stefania Nosotti: Tanystropheus longobardicus (Reptilia, Protorosauria): re-interpretations of the anatomy based on new specimens from the Middle Triassic of Besano (Lombardy, northern Italy). In: Memorie della Società Italiana di Scienze Naturali e del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano. Vol. 35, No. 3, 2007 ( full text on ResearchGate ); see also literature cited therein.

- ↑ a b c Olivier Rieppel, Da-Yong Jiang, Nicholas C. Fraser, Wei-Cheng Hao, Ryosuke Motani, Yuan-Lin Sun, Zuo-Yu Sun: Tanystropheus cf. T. longobardicus from the early Late Triassic of Guizhou Province, southwestern China. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 30, No. 4, pp. 1082-1089, doi: 10.1080 / 02724634.2010.483548

- ↑ a b c d e Stephan NF Spiekman, James M. Neenan, Nicholas C. Fraser, Vincent Fernandez, Olivier Rieppel, Stefania Nosotti, Torsten M. Scheyer: Aquatic habits and niche partitioning in the extraordinarily long-necked Triassic reptile Tanystropheus. In: Current Biology . 2020 (in press), doi: 10.1016 / j.cub.2020.07.025

- ^ A b c Karl Tschanz: Allometry and heterochrony in the growth of the neck of Triassic prolacertiform reptiles. In: Palaeontology. Vol. 31, No. 4, 1988, pp. 997-1011 ( PalAss ).

- ^ Franz Nopcsa: New description of the Triassic pterosaur Tribelesodon. In: Palaeontological Journal. Vol. 5, No. 3, 1923, pp. 161-181, doi: 10.1007 / BF03160365 .

- ↑ Eberhard Fraas: The Swabian Triassic Saurians. Schweizerbart, Stuttgart 1896, urn : nbn: de: bsz: 21-dt-46495 , p. 11 .

- ↑ Olivier Rieppel: A revision of the genus Nothosaurus (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Germanic Triassic, with comments on the status of Conchiosaurus clavatus. In: Fieldiana Geology, new series. No. 34, 1996 doi: 10.5962 / bhl.title.2691 , p. 61 .

- ^ A b Friedrich von Huene: The Triassic Dinosaurs of Europe. In: Journal of the German Geological Society . Vol. 57, 1905, pp. 345-349 ( BHL ), p. 349 .

- ↑ a b c Friedrich von Huene: The dinosaurs of the European triad formation, with consideration of the non-European occurrences. In: Geological and Palæontological Treatises . Suppl.-Vol. 1, 1907-1908 ( archive.org ).

- ^ Andrey G. Sennikov: New tanystropheids (Reptilia: Archosauromorpha) from the Triassic of Europe. In: Paleontological Journal. Vol. 45, No. 1, 2011, pp. 90-104, doi: 10.1134 / S0031030111010151 (alternative full text access : ResearchGate ).

- ^ A b Edward D. Cope: A Contribution to the History of the Vertebrata of the Trias of North America. In: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. Vol. 24, No. 126, 1887, ( BHL ), p. 221 ff.

- ^ Matthew T. Carrano, Roger BJ Benson, Scott D. Sampson: The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda). In: Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. Vol. 10, No. 2, 2012, pp. 211-300, doi: 10.1080 / 14772019.2011.630927 (alternative full text access : ResearchGate ), p. 227.

- ↑ a b Emil Kuhn-Schnyder: The Triassic Fauna of the Ticino Limestone Alps. Neujahrsblatt 1974, Naturforschende Gesellschaft in Zürich, 1973 ( PDF 25 MB), pp. 50–57.

- ↑ Francesco Bassani: Sui fossili e sull'età degli schisti bituminosi triasici di Besano in Lombardy. In: Atti della Società Italiana di Scienze Naturali. Vol. 19, 1886, pp. 15-72 ( BHL ), pp. 25 ff.

- ^ Nicholas C. Fraser, Olivier Rieppel: A new protorosaur (Diapsida) from the Upper Buntsandstein of the Black Forest, Germany. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 26, No. 4, 2006, pp. 866-871, doi : 10.1671 / 0272-4634 (2006) 26 [866: ANPDFT] 2.0.CO; 2 , p. 866.

- ↑ Silvio Renesto: A reappraisal of the diversity and biogeographic significance of the Norian (Late Triassic) reptiles from the Calcare di Zorzino. Pp. 445-456 in: Jerry D. Harris, Spencer G. Lucas, Justin A. Spielmann, Martin G. Lockley, Andrew RC Milner, James I. Kirkland (Eds.): The Triassic-Jurassic Terrestrial Transition. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. Vol. 37, 2006 ( online ).

- ^ A b c Rupert Wild: Tanystropheus H. von Meyer, [1852] (Reptilia): Revised request for conservation under the plenary powers. ZN (S.) 2084. In: Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. Vol. 33, No. 2, 1976, pp. 124-126 ( BHL ).

- ^ A b RV Melville: Opinion 1186. Tanystropheus H. von Meyer, [1852] (Reptilia) conserved. In: Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. Vol. 38, No. 1, 1981, pp. 188-190 ( BHL ).

- ^ Bernhard Peyer: Demonstration of Triassic vertebrates from Palestine. In: Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae. Vol. 48, No. 2, 1955, pp. 486–490 ( PDF 98 MB; includes the entire scientific part of the report on the 34th annual meeting of the Swiss Paleontological Society).

- ↑ Olivier Rieppel: A new species of Tanystropheus (Reptilia: Protorosauria) from the Middle Triassic of Makhtesh Ramon, Israel. In: New Yearbook of Geology and Paleontology, Treatises. Vol. 221, No. 2, 2001, pp. 271-287, doi: 10.1127 / njgpa / 221/2001/271

- ↑ Li Chun: A juvenile Tanystropheus sp. (Protorosauria, Tanystropheidae) from the Middle Triassic of Guizhou, China. In: Vertebrata PalAsiatica . Vol. 45, No. 1, 2007, pp. 37-42 ( PDF 550 kB).

- ↑ Hans-Dieter Sues, Paul E. Olsen: Stratigraphic and temporal context and faunal diversity of Permian-Jurassic continental tetrapod assemblages from the Fundy rift basin, eastern Canada. Atlantic Geology. Vol. 51, No. 1, 2015, pp. 139–205, doi: 10.4138 / atlgeol.2015.006 (Open Access), Fig. 10

- ^ Paul E. Olsen: Paleontology and paleoecology of the Newark Supergroup (early Mesozoic, eastern North America). Pp. 185-230 in: Warren Manspeizer (Ed.): Triassic-Jurassic Rifting: Continental Breakup and the Origin of the Atlantic Ocean and Passive Margins. Developments in Geotectonics 22. Elsevier, Amsterdam / New York 1988, ISBN 0-444-42903-4 , p. 189 (Fig. 8-4), 221

- ^ Phillip Huber, Spencer G. Lucas, Adrian P. Hunt: Vertebrate biochronology of the Newark Supergroup Triassic, eastern North America. Pp. 179-186 in: Spencer G. Lucas, Michael Morales (Eds.): The Nonmarine Triassic. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. Vol. 3, 1993 ( online ), p. 180.

- ^ Susan E. Evans: The early history and relationships of the Diapsida. Pp. 221-260 in: Michael J. Benton (Ed.): The Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapoda. Volume 1: Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds. Systematics Association Special Volume 35A. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1988 ( digitized on ResearchGate ), p. 227.