Antiochus palace

The Palace of Antiochus ( Greek τὰ παλάτια τῶν Ἀντιόχου ) was a Byzantine palace from the early 5th century AD in Constantinople . In the 1940s and 1950s, the remains were discovered and uncovered during excavations near the hippodrome . In the 7th century, part of the palace was converted into the Church of St. Euphemia in the Hippodrome ( Greek Ἀγία Εὐφημία ἐν τῷ Ἱπποδρομίῳ , Hagia Euphēmia en tō Hippodromiō ) and used as a martyrdom .

history

The palace of Antiochus was built for the Praepositus sacri cubiculi Antiochus . Antiochus was head of the eunuchs who were responsible for the imperial apartments and the cloakroom of the emperor in the palace. Antiochus probably came from Persia and had far-reaching influence on the young Byzantine emperor Theodosius II. As chamberlain , he was the young emperor's teacher and probably rose to the rank of Patricius . His dominant behavior towards the emperor led to his overthrow by the emperor's sister Aelia Pulcheria , but he was allowed to return to the palace and live here. Antiochus then remained active in politics until he finally fell out of favor and around 439 joined the clergy. Thereupon his property, which also included the palace, was confiscated by the emperor.

The remains of the palace were discovered in 1939 when frescoes were uncovered northwest of the hippodrome depicting the life of St. Euphemia of Chalcedon . The following excavations by Alfons Maria Schneider in 1942 uncovered a hexagonal hall that opened to a semicircular colonnade , while excavations in 1951/52 under R. Duyuran exposed a column base with the inscription of the praepositus Antiochus, which made identification possible . Based on stamps on the bricks, it is believed that the palace was not built before 430.

Euphemia Church

The church of St. Euphemia in the hippodrome was built in the hexagonal hall possibly in the 7th century when the Euphemia church in Chalcedon was destroyed by the Persian Sassanids and the relics were brought to the safe Constantinople. Originally the western chapel was frescoed with the martyrdom of St. Euphemia decorated. The sanctuary had a dome. During the Byzantine iconoclasm , the building was secularized and turned into a warehouse for weapons and dung. According to tradition, the bones of the saints were to be ordered by Emperor Leo III. or his son Constantine V would be thrown into the sea. However, they were saved by two pious brothers and brought to Lemnos , from where they were brought back by Empress Eirene in 796 after the Second Council of Nicaea . The church has been restored.

description

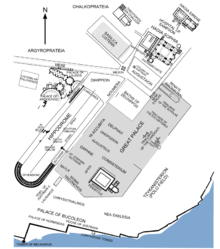

The palace consisted of a southern and a northern building complex. The southern one, not open to the public today, had a large hexagonal hall with an apse , which was connected with a wide semicircular colonnade, which was around 60 meters in diameter and enclosed a courtyard paved with marble. The hall was possibly used as a dining room ( triclinium ). It had a diameter of about 20 meters and walls 10.4 meters wide. Each wall had an apsidal wall niche that was polygonal on the outside and semicircular on the inside. Each niche was 7.65 meters wide and 4.65 meters deep and provided space for a stibadium and a dining table. Each alcove also had a door that led to small circular spaces between the alcoves. A marble basin stood in the center of the hall. The hexagonal triclinium was flanked by other rooms around the portico, including a spacious vestibule with a round room in the center.

It is controversial whether the northern building complex along the road west of the Hippodrome and the Mese is part of the Antiochus Palace or the Palace of Lausos . It comprised a large rotunda with a diameter of 20 meters and wall niches that could have been used as an audience hall by Antiochus. It adjoined the southeast street facade, which was opened as a C-shaped portico to the hippodrome. A small bath house, also accessible from the street, adjoined the portico to the south. In the 5th century, when the palace was imperial property, a long corridor was added to the rotunda in the west, which was entered through a vestibule with two side apses. Its shape reveals it as a triclinium . It was 52.5 meters long and 12.4 meters wide and had a wide apse at the end. In the 6th century, three niches were added to the long sides.

When the hexagonal hall was converted into a church, some changes were made. The bema was set up to the right of the original entrance in the apse facing southeast and a new entrance was created in the opposite apse. The original gate remained, but was later reduced in size. Two more gates were broken through in the two northern rooms, to which four mausoleums were later added.

literature

- Rudolf Naumann , Hans Belting : The Euphemia Church at the Hippodrome in Istanbul and its frescoes . Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1966.

- Rudolf Naumann: Preliminary report on the excavations between Mese and Antiochus Palace in 1964 in Istanbul. In: Istanbul communications. 15, 1965, pp. 135-148.

- Albrecht Berger : The relics of Saint Euphemia and their first translation to Constantinople. In: Hellenika. 39, 1988, pp. 311-322.

- E. Torelli Landini: Note sugli scavi a north ovest dell'Ippodromo di Istanbul (1939/1964) e loro identificazione. In: Storia dell'Arte. 68, 1990, pp. 5-35.

Web links

- Jan Kostenec: Palace of Antiochus. In: Constantinople. (= Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World . Volume 3). Foundation of the Hellenistic World, Athens 2008 (digitized version)

- Amanda Ball: Church of St. Euphemia. In: Constantinople. (= Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World . Volume 3). Foundation of the Hellenistic World, Athens 2008 (digitized version)

- Reconstruction , Byzantium 1200 project

- Palace of Antiochus , The byzantine legacy (photos)

- Hag. Euphemia en to Hippodromo , plans and cross-sections of the building by Thomas Mathews in the project The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul , Institute of Fine Arts, New York University

Individual evidence

- ↑ John R. Martindale, AHM Jones, J. Morris: The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire . Volume 2: AD 395-527. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1992, ISBN 0-521-20159-4 , pp. 101-102.

- ↑ Jonathan Bardill: Brickstamps of Constantinople . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004, ISBN 0-19-925524-5 , pp. 57-59.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Kostenec (2008)

- ↑ Jonathan Bardill: Brickstamps of Constantinople . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004, ISBN 0-19-925524-5 , p. 56.

- ↑ Jonathan Bardill: Brickstamps of Constantinople . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004, ISBN 0-19-925524-5 , pp. 107-109.

- ↑ Alexander Kazhdan : Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-504652-8 , p. 747.

- ↑ Averil Cameron, Judith Herrin: Constantinople in the early eighth century: the Parastaseis syntomoi chronikai. Introduction, translation, and commentary . Brill, Leiden 1984, ISBN 90-04-07010-9 , pp. 22, 63.

- ^ Jelena Bogdanovic: The Framing of Sacred Space . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2017, pp. 190–193.

- ^ Averil Cameron, Judith Herrin: Constantinople in the early eighth century. 1984, p. 22.

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-504652-8 , pp. 747-748.

- ↑ Amanda Ball: Church of St. Euphemia. 2008.

Coordinates: 41 ° 0 ′ 26.6 ″ N , 28 ° 58 ′ 30.4 ″ E