Bone Wars

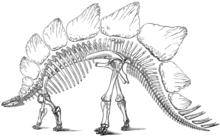

Bone Wars ( dt . "Bone Wars") is a in the US used the press and popular scientific literature notion of personal and scientific examination of the two American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope in the late 19th century describes . Over 142 new species of dinosaurs were discovered during the two men's feud, including species such as Triceratops , Diplodocus , Stegosaurus , Allosaurus, and Camarasaurus .

Marsh and Cope

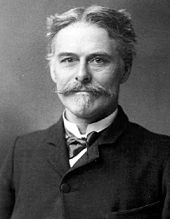

Othniel Charles Marsh was the nephew of the industrialist and banker George Peabody , who supported and encouraged him financially and bequeathed large parts of his fortune to him. These funds later enabled him to carry out research trips at his own expense and to pay qualified employees out of pocket. Marsh studied in Andover, Massachusetts and at Yale . At his suggestion, Peabody donated a museum to the university (now the Peabody Museum of Natural History ), on condition that Marsh was given a professorship there, which he took up in 1866 and held until the end of his life. Marsh was trained as a geologist, not a paleontologist, and had no special knowledge of vertebrate anatomy. He made up for this by hiring qualified paleontologists, forbidding them to publish under his own name, so that all results appeared under his own name. He was respected for his energy and vigor, but was hated within paleontology for his selfishness and had no friends in the field; all of his former assistants later became bitter enemies of him without exception.

Edward Drinker Cope was born into a Quaker family and was raised religiously. At the age of 16 he was supposed to take over his parents' farm, but continued his education after four years because of his scientific interests. He was trained by the eminent paleontologist Joseph Leidy , among others , and worked temporarily at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. In 1864 he received a professorship at Harvard , which he gave up in 1868 in order to devote himself exclusively to paleontological research. Unlike his rival Marsh, Cope also had a personal reputation as a vertebrate paleontologist. In his private life he was seen as sociable and friendly.

Marsh and Cope met personally at a meeting in Europe in the early 1860s. What is certain is that both had respect for each other and also established a friendship. When they both went back to work in the US, they often did so together at first. Both of them researched a site on the New Jersey coast (near Haddonfield ), where Cope began to search the marl pits for fossils. Marsh read Cope's article on this and suggested that the friend examine the pit together. The respect between them was so great that they even named finds after the other. Cope named a lizard Colosteus marshii , Marsh retaliated with Mosasaurus copeanus at his friend.

At that time the two were not yet "dinosaur hunters". Only one dinosaur was discovered in North America before Marsh and Cope : A Hadrosaurus by Joseph Leidy (1858) in New Jersey. Cope also discovered the second dinosaur in New Jersey and named it Laelaps aquilunguis (today after Marsh Dryptosaurus ). The vast majority of the spectacular sites are in the west of the continent, the exploration of which only began at this time, after the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad . Government agencies began during this time to support scientific research in the newly conquered territories in the west, which were then later (1879) united to the United States Geological Survey, which both Marsh and Cope used. In the 1870s, as head of a Yale research company, Marsh led a series of expeditions to the Rocky Mountains for which he paid for himself. Although financially poorer, Cope was also able to conduct research here. Both were able to access the resources and support of various government research teams.

Marsh versus Cope

As a result of this development, Marsh and Cope were now scientific rivals in a productive, new field of research. Both began to describe their finds at high speed , probably also in order to forestall their rival, who had access to similar material, so where the same species could be discovered. Marsh had the exclusive use of the American Journal of Science published in Yale for this purpose. To keep up, Cope took on the editing of the American Naturalist and later, to go even faster, founded his own journal Palaeontological Bulletin. In the course of time the relationship between the two became more and more tense, they now also openly published polemics and disparaging reports about the results of their competitors.

Due to his influence and the better networking in leading circles, Marsh was initially far more successful in the 1870s. He succeeded in becoming the official vertebrate paleontologist of the US Geological Survey, whose resources were now exclusively at his disposal. At the same time, he began to use his influence to thwart the publication of Cope's research behind the scenes. Since he was denied state funds due to Marsh's influence, he tried to speculate in mining stocks to raise money, but lost most of his remaining financial resources. In 1889 he was able to avert ruin by accepting a professorship at the University of Philadelphia. The tide turned in 1892 when Marsh lost his position with the Geological Survey and its associated resources and leverage due to financial extravagance. Since his immense personal income was no longer enough to finance his lavish lifestyle and ambitious publication plans, he had to ask the university for a salary as a professor for the first time in his life. Cope's situation improved at the same time when he succeeded Leidy at the chair, and he also sold parts of his fossil collection to the American Museum of Natural History for a large sum.

Some anecdotal accounts can illustrate the hostility.

The Elasmosaurus Discussion

In 1869 the spark for the "fight for the bones" was probably set. Cope had made a mistake in a reconstruction of the Elasmosaurus platyrus . He had mistaken the head part for the tail part. When Marsh saw that he had to laugh for a long time and pointed out the mistake to his colleague. The experts hardly noticed it, but Cope must have taken it so badly that he insisted on getting his colleague back.

Smoke Hill River

Marsh pulled out of New Jersey and headed west. Among other things, he was accompanied by Buffalo Bill (William Cody), who, according to him, was a lifelong friend. During the tour, they stopped at the Loup Fork River . Here Marsh brought to light numerous bones of camels, rhinos and other mammals. In Kansas near the Smoky Hill River he finally found another promising deposit of fossils. Among other things, he found the remains of a pterosaur , which exceeded all known specimens from Europe in size. When Cope heard of the find, he followed his colleague, who had, however, moved on in the meantime. However, that did not prevent Cope from looking for more evidence of the past and he found it here. On the one hand he found a relic of the mosasaur , on the other hand he also discovered a pterosaur that was larger than Marsh's. In addition, Cope dug up his second dinosaur here, while Marsh hadn't found one yet.

The Rocky Mountains

The next stage of the bone war also took place in the western United States. Marsh staked his first claim in the Uinta Mountains - here he alone claimed the right to excavate. Cope had accepted this and was only digging on the edge of the Marsh claimed zone. Also on site was the researcher Joseph Leidy , who roamed the outskirts here. As luck would have it, all three discovered a new mammal at almost the same time, and each described it for himself. Marsh called the animal Dinoceras , Cope called it Loxolophodon , and Leidy named it Uintatherium . Since Leidy was proven to be the first to be discovered, the animal is now also called that, and the two rivals lost out.

Separate ways

The two researchers contested the next few years in different territories. While Cope undertook a large expedition to Missouri to the Judith River in the immediate vicinity of the Crow Indians and found what he was looking for there, Marsh ended up in the Black Hills , which were in Sioux territory and also the famous site of the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876 wasn't far from it. Both areas were hotly contested between the new settlers and the native Indians. Cope gained the respect and esteem of the Indians by displaying his dentures - a tool completely unknown to the Indians. Marsh, on the other hand, proceeded diplomatically: He promised the Sioux chief Red Cloud that he would make the situation of the Sioux in Washington known and audition for them. He did that too - although it had little effect. Nevertheless, this ensured his friendship with the tribe and safe work in the region.

Cope was now the first to successfully report a dinosaur find: He baptized it with the name Monoclonius , which is a Ceratopier ("horn dinosaur"). Marsh had the better hand in this game, however: his findings were so enormous that he was able to send a shipment of two tons of fossils to the Peabody Museum , which his uncle donated to Yale.

The end of the Bone Wars

There was never any reconciliation between the two researchers. Cope died of kidney failure in 1897, Marsh of pneumonia in 1899. However, the dispute had already settled before that. After Marsh lost his position and his influence in harming Cope, an important source of hostility was gone. Cope became more sedentary towards the end of his life. Although he undertook one last research trip to the West in 1893, he largely limited himself to publishing on the material already available. Marsh, too, now lacked the means to maintain his restless activity in the usual style. In 1896 he published his monumental work "The Dinosaurs of North America" and tried, unsuccessfully, to initiate a large new museum building to present his finds appropriately. Shortly before his death, he donated all of his finds to the Peabody Museum, where they are exhibited to this day.

During the entire time, the two researchers discovered and scientifically described many new species, Marsh discovered a total of 86 dinosaur genera and Cope 56, plus descriptions of many other fossils from the Mesozoic era . In one case, a find resulted in 16 scientific descriptions with a total of 22 names.

In order not to leave any new finds to the other, the hired excavation helpers were also used for acts of sabotage. This went so far that abandoned sites were cleared as a final thesis of possible further fossils by destroying them in order to withhold them from the respective opponent. It is impossible to tell how many fossils of scientific value were lost as a result.

According to Alfred Romer's judgment, both researchers were losers in the dispute. After the Bone Wars, later researchers were busy organizing the finds and giving them valid scientific names for decades. Due to the often hasty and hasty descriptions as a result of the feud, the research was in some cases even hindered, many scientific names remained unexplained for decades.

literature

- Edwin Colbert: The Great Dinosaur Hunters and Their Discoveries. Courier Dover Publications 1984

- Mark Jaffe: The Gilded Dinosaur: The Fossil War Between ED Cope and OC Marsh and the Rise of American Science. New York: Crown Publishing Group 2000

- Henry Fairfield Osborn: Cope: Master Naturalist: Life and Letters of Edward Drinker Cope, With a Bibliography of His Writings. Manchester, New Hampshire: Ayer Company Publishing 1978

- Elizabeth Shor: The Fossil Feud Between ED Cope and OC Marsh. Detroit, Michigan: Exposition Press 1974

- David Rains Wallace: The Bonehunters' Revenge: Dinosaurs, Greed, and the Greatest Scientific Feud of the Gilded Age. Houghton Mifflin Books 1999

- John Noble Wilford: The Riddle of the Dinosaur. New York: Knopf Publishing 1985

- Herbert Wendt: Before the flood came. Researchers discover the primeval world. List, Munich 1997