Stegosaurus

| Stegosaurus | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

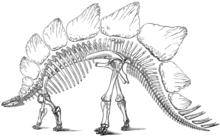

Reconstruction of a Stegosaurus skeleton in the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Upper Jurassic ( Kimmeridgian to Lower Tithonian ) | ||||||||||||

| 157.3 to 147.7 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Stegosaurus | ||||||||||||

| Marsh , 1877 | ||||||||||||

| species | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

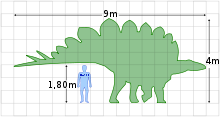

Stegosaurus is a thyrophore (shield-bearing) dinosaur from the family of the Stegosauridae and thus a representative of the Ornithischia (bird basin dinosaur), which lived in the Upper Jurassic ( Kimmeridgian to early Tithonian ). With a length of up to 9 meters, it was the largest known representative of the stegosauria . The name Stegosaurus means something like "badger" (ancient Greek στέγος stegos "roof", σαῦρος sauros "lizard").

At least three different species have been recovered from the lower Morrison Formation in western North America, with the remains of about 80 individuals in total. A find from Portugal in 2006 showed that the genus also occurred in Europe. With its imposing bone plates and tail spines, Stegosaurus is - together with Tyrannosaurus , Triceratops , Apatosaurus and Velociraptor - one of the most popular dinosaurs of all.

Stegosaurus was a large, heavily built and quadruped (four-legged) herbivore with an unusual posture: the back was strongly arched, the front legs were short. The animal held its tail high in the air while its head was held close to the ground. Its various bone plates and tail spines were the subject of much speculation. While the latter was very likely used for defense, functions such as defense, temperature regulation or courtship have been suggested for the bone plates.

description

Stegosaurus stenops , the type species, was about seven meters long and a little over three meters high; the remains of Stegosaurus armatus suggest a total length of nine meters. On the neck, back and tail, flat, kite-shaped plates of different sizes ran in two rows, the number of which varied between 17 (in Stegosaurus stenops ) and 22. In conjunction with the long tail spines that stood in two pairs near the tail end, these make Stegosaurus an easily identifiable dinosaur for the layman.

The hind feet each have three short toes, while each forefoot has five toes. Only the inner two toes had a blunt hoof. All four legs were supported by pads behind the toes. The front legs were much shorter than the back legs, which resulted in an unusual posture. So the tail was kept high above the ground while the head was kept relatively flat - presumably it was no higher than three feet above the ground.

The elongated and thin skull was small compared to the rest of the body. The low position of the skull suggests that Stegosaurus has grazed low-growing vegetation. This is aided by the absence of front teeth and the presence of a horned beak. The small teeth were triangular, flat, and serrated, suggesting that the animal was crushing its food before swallowing it. Cheeks presumably ensured that Stegosaurus could keep its food in its mouth while chewing.

Despite the overall size of the animal, the skull was small and no larger than that of a dog. A well-preserved Stegosaurus brain shell allowed Othniel Charles Marsh , who first described Stegosaurus , to make a cast that gave an indication of the Stegosaurus brain size . As the cast showed, the brain was very small - perhaps the smallest of all dinosaurs. The fact that an animal like Stegosaurus weighing over 4.5 tons could have a brain as small as 80 grams contributed significantly to the earlier popular idea that dinosaurs were extremely stupid - an assumption that is largely rejected today.

Most of the knowledge about Stegosaurus comes from the remains of adult animals; Recently , however, remains of Stegosaurus juveniles have also been discovered. One such find was made in Wyoming in 1994 - the animal was 4.6 meters long, two meters high, and its weight is estimated at 2.3 tons. The skeleton can be viewed today at the University of Wyoming Geological Museum. Even smaller skeletons - with a length of up to 210 centimeters and a back height of 80 centimeters - can be viewed in the Denver Museum of Nature & Science.

Systematics

Stegosaurus was the first named genus of the Stegosauridae family. He is the type genus and namesake of the family. The Stegosauridae are one of two families within the Stegosauria infraorder , along with the Huayangosauridae . Stegosauria form together with Ankylosauria the group Thyreophora . Stegosaurs were similar in physique and differed mainly in their range of spines and plates. The closest relatives of Stegosaurus include Wuerhosaurus from China and Kentrosaurus from East Africa.

Origins

The origins of Stegosaurus are uncertain - only a few remains of basal stegosaurs and their ancestors are known. Recently, a new stegosaur - Hesperosaurus - was discovered from the lower Morrison formation. This find from the early Kimmeridgian is several million years older than the remains of Stegosaurus . The earliest known representative of the Stegosauridae, Lexovisaurus , comes from the Oxford Clay Formation in England and France and lived in the early to middle Callovian .

The earlier and more original genus Huayangosaurus from the middle Jurassic of China (about 170 million years ago) lived about 20 million years earlier. It is the only known genus in the Huayangosauridae family. Even older is Scelidosaurus , from the early Jurassic of England, which lived about 190 million years ago. Scelidosaurus showed features of both stegosaurs and ankylosaurs. Emausaurus from Germany is another basal thyrophore, while the bipede (walking on two legs) Scutellosaurus from Arizona (USA) was an even earlier genus. This small, lightly armored dinosaur is believed to be closely related to the direct ancestors of stegosaurs and ankylosaurs. A fossil track about 195 million years old, presumably from an early stegosaur or a stegosaur ancestor, was discovered in France.

Discovery and species

Stegosaurus , one of many dinosaurs first discovered and described during the " Bone Wars, " was named by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1877 from remains discovered north of Morrison , Colorado . These first bones became the holotype - Stegosaurus armatus . Marsh named the animal Stegosaurus , which means something like "badger lizard", because he initially thought the plates lay flat on the animal's back and would overlap like roof tiles. In the years after it was first described, a wealth of other material was discovered and Marsh published other papers on the genus. Many different species were initially described - but many of these were subsequently declared invalid or synonymous with other species.

Valid types

Stegosaurus stenops , "narrow-headed badger", was named by Marsh in 1887. The holotype material had been discovered the previous year by Marshal Felch in Garden Park, north of Cañon City , Colorado . This is the best known species of Stegosaurus because at least one complete connected skeleton has been recovered. Furthermore, at least 50 partial skeletons - both from adult animals and from young animals - one complete skull and four partial skulls are known. Stegosaurus stenops had large, broad plates and four tail spines. At seven meters in length, it was shorter than Stegosaurus armatus . Stegosaurus stenops has been a type species since 2013 .

Stegosaurus ungulatus , which means “badger with a hoof”, was named by Marsh in 1879 from remains discovered in the famous Como Bluff dinosaur cemetery in Wyoming. It is known from a few vertebrae and bone plates. Perhaps it is a juvenile of Stegosaurus armatus , although the original material of the latter species has not yet been fully described. A find from Portugal, which was dated from the Upper Kimmeridgian to the Lower Tithonian , was ascribed to this species.

Nomina dubia (species subsequently declared "invalid")

Stegosaurus armatus , "armored badger", was the first species to be discovered and is known from two partial skeletons, two partially preserved skulls and at least thirty fragmentary finds. This species had four horizontal tail spines and relatively small plates. With a length of nine meters, it was the longest species. Stegosaurus armatus was long considered a type species, but lost this status due to few findings.

Stegosaurus sulcatus , "furrowed badger", was described by Marsh in 1887 based on a partial skeleton. Long considered as a possible synonym of Stegosaurus armatus , more recently the view has even been taken that it could be a genus of its own.

Stegosaurus duplex , which means something like "badger lizard with two nerve plexuses" (alluding to the greatly enlarged neural canal on the sacrum ), was described by Marsh in 1887. The remains were recovered by Edward Ashley in Como Bluff, Wyoming, in 1879. This species is now considered to be the younger synonym of Stegosaurus ungulatus .

Stegosaurus seeleyanus , originally described as Hypsirophus , is possibly also identical to Stegosaurus armatus .

Stegosaurus (syn. Diracodon ) laticeps was described by Marsh in 1881 based on some jawbone fragments. While some Stegosaurus consider stenops to be a species of Diracodon , others classify Diracodon as a Stegosaurus species. Bakker reintroduced the name Diracodon laticeps in 1986 , although others note that the material is likely synonymous with Stegosaurus stenops .

Stegosaurus affinis , described by Marsh in 1881, is only known from a lost pubis (pubic bone). It may be identical to Stegosaurus armatus .

Doubtful species

Stegosaurus madagascariensis from the early Upper Cretaceous of Madagascar was described by Jean Piveteau in 1926 on the basis of two isolated teeth . The morphology of these teeth is obviously anything but stegosaur-typical and has since been ascribed to the theropod Majungasaurus , a hadrosaur , the pachycephalosaur Majungatholus atopus , a strongly derived crocodile relative ( Simosaurus clarki ) and ankylosaurs that cannot be identified .

Species described

Further material, originally described as Stegosaurus remains, is now ascribed to other species:

- Stegosaurus marshi , described by Lucas in 1901, was renamed Hoplitosaurus the following year .

- Stegosaurus priscus , described by Nopcsa in 1911, is identical to Lexovisaurus .

- Stegosaurus longispinus ("badger with long spines") was named in 1914 by Charles W. Gilmore based on a partial skeleton that came from the Morrison Formation, Wyoming . The four unusually long tail spines of this approximately seven-meter-long animal gave rise to decades of speculation as to whether this was actually a Stegosaurus species. Since 2016 it has been the type species of the genus Alcovasaurus .

Fossil footprints

Fossil footprints of stegosaurids are extremely rare, not a single one was known before 1996. Some researchers suspect that stegosaurs inhabited dry areas and that this is why so few trace finds have emerged. However, there are two reports of finds from North America that would also fit Stegosaurus in time . The first report comes from an imprint of the forefoot (manus) discovered in Utah, which was described by Lockley and Hunt in 1998 and called Stegopodus czerkasi (such an Ichnotaxon is not a regular species in the biological sense, but only describes the footprint). A rear footprint was discovered on the same specimen; however, since it was not sure whether it came from the same animal, it was not assigned to the stegopodus . The second report, published by Bakker in 1996, describes hind foot prints.

Stegopodus means as much as Stegosaurus foot, but whether it really comes from the genus Stegosaurus is not unequivocally established. Some researchers are of the opinion that both finds do not belong to a stegosaurid.

Paleobiology

After the species was discovered, Marsh first suspected Stegosaurus was biped based on its short front legs . In 1891, he changed his mind considering the very heavily built skeleton. Although Stegosaurus is now considered to be undoubtedly quadruped , there have been discussions as to whether the animal might not have stood on its hind legs in order to graze higher vegetation using the tail as a third support leg. This idea was suggested by Bakker but later rejected by Carpenter.

Stegosaurus had very short front legs compared to its hind legs. Furthermore, the lower section of the hind legs ( tibia and fibula ) was relatively short compared to the femur . This means that the animal could not have walked particularly fast - the maximum speed was 6–7 km / h.

Second brain

Soon after describing the animal, Marsh noticed a large cavity in the pelvic region of the spinal canal that could house a structure up to 20 times larger than the brain. This led to the famous idea that dinosaurs like Stegosaurus had a kind of "second brain" at the base of their tails, which should have been used to control reflexes in the back of the body. It was also suspected that it temporarily provided reinforcement for the animal when attacked by Predators. More recently it has been theorized that the cavity, which was also found in sauropods, housed a glycogen body. Such a structure is found in recent birds, although its function is not yet exactly known - it is assumed that they supplied the animals' nervous system with glycogen.

plates

The most striking feature of Stegosaurus is undoubtedly its bone plates. These highly developed osteoderms stick to the skin and, like the bone platelets of recent crocodiles and many lizards, were not directly connected to the skeleton. The largest plates were found above the animal's hips and measure 60 cm in width and 60 cm in height. Their arrangement has long been debated - there are the following hypotheses:

- The plates lay flat on the animal's back, like armor. This was Marsh's initial interpretation, which Stegosaurus owes its name "badger". When more and more complete plates were found, their shape indicated that they were standing, not lying on the skin.

- In 1891, Marsh published another reconstruction, this time the plates were in a single row. However, this theory, too, was soon abandoned, probably because it was difficult to understand how the plates were embedded in the skin, and because the plates would overlap too much in such an arrangement.

- The plates were arranged in pairs in a double row. This is the most common arrangement especially in older pictures up to the "Dinosaur Renaissance" in the 1970s. For example, the stegosaurus in the 1933 film King Kong had this arrangement. So far, however, no two plates of identical size and shape have been found in the same animal.

- Already at the beginning of the 20th century, the now widely accepted view arose that the panels were arranged alternately (“in a gap” or “in a zigzag”) in two rows. This idea is mainly based on the find situation of complete Stegosaurus skeletons, which shows this arrangement. The fact that no two plates of identical size and shape have so far been found in the same animal and that the number and size of the plates effectively rule out an arrangement in a single row speaks for this configuration. One objection to this hypothesis is that such an unpaired arrangement of osteodermal structures is completely unknown in other reptiles and that it is difficult to understand how evolution could produce it.

The function of the panels has also been the subject of much discussion. Initially they were thought of as armor, but they seem too fragile and inconveniently placed as they would leave the animal's sides unprotected. Later the theory spread that the plates were used to regulate temperature - similar to the sail of the carnivorous Spinosaurus or the Pelycosaur Dimetrodon (or the ears of recent elephants and rabbits ). The plates had blood vessels running through furrows, and air flowing past would have cooled the blood. This theory has been seriously challenged because a close relative of Stegosaurus stenops had very small plates that would be unsuitable for cooling.

In the past, some researchers, notably Robert Bakker, speculated that the plates could have been movable to some extent. Bakker said the plates were just the bony kernels of pointed horn coatings that the animal might have hit from side to side to hold out a series of tips against attackers. He imagined the plates lying flat on his back, as they seemed too narrow to be able to stand upright without strong muscle activity. He suspected the horn coverings because the plates resembled the bony base of many other horned animals.

Today theories based on visual functions have come to the fore. Possibly. the large plates were used to increase the apparent height of the animal, either to intimidate enemies or to impress other species. Some form of sexual display would be possible, although both males and females appear to be wearing plates. A study published in 2005 supports the assumption that the plates were used for identification. The researchers believe this could have been the function of different dinosaur traits from different species.

Tail spines

There was debate as to whether the tail spines were just for show, as Gilmore suggested in 1914, or whether they were used as a weapon. Robert Bakker noted that the tail was much more agile than that of other dinosaurs due to the lack of ossified tendons - this made the assumption that the tail might have been used as a weapon more likely. In any case, Carpenter said that mobility was limited because the bone plates overlapped too many caudal vertebrae. Bakker also observed that Stegosaurus was able to wiggle its tail skillfully by keeping its hind legs on the ground and jumping to one side with its muscular but short, front legs. Later, a study of the tail spines by McWhinney et al. frequent damage, confirming the theory that the tail spines may have been used in combat. Further evidence is a pierced tail vertebra of the Carnivore Allosaurus , into which a Stegosaurus tail spine fits perfectly.

Stegosaurus stenops had four dermal tail spines, each about 60–90 cm long. Discoveries of interconnected Stegosaurus shells showed that at least in some species the spines protruded horizontally from the tail rather than vertically, as can be seen in many pictures. Marsh initially described Stegosaurus armatus with eight tail spines, in contrast to Stegosaurus stenops with four. However, later research showed that Stegosaurus armatus also had four tail spines.

nutrition

The feeding behavior of Stegosaurus and related species differs from that of other herbivorous ornithischia. Other ornithischia had teeth with which they could grind plant material and a jaw that enabled them to chew-like movements. In contrast, stegosaurs had small, serrated teeth for crushing plant material and a jaw that was likely to allow only simple movements and was not suitable for proper chewing.

Still, stegosaurs must have been successful because they were geographically widespread in the Jurassic. Paleontologists suspect that stegosaurs ate mosses , ferns , cycads , conifers or fruits. To do this, they probably swallowed gastroliths - stones that help break up food in the stomach, in the same way that some recent, non-chewing animals like birds or crocodiles do. Grazing of grass, as seen in many modern herbivorous mammals, would not have been possible for Stegosaurus - the first grasses only appeared in the Cretaceous long after Stegosaurus became extinct.

Stegosaurus probably only grazed near the ground at a height of about one meter. However, if Bakker's hypothesis that Stegosaurus could stand on its hind legs is correct, adult animals would have been able to eat up to six meters above the ground.

Stegosaurus in popular culture

As one of the most notable dinosaurs, Stegosaurus often appears in films, cartoons, and comics. It is also an important part of many dinosaur model and toy collections, such as the Carnegie collection. In 1982, Stegosaurus was chosen as the state dinosaur of Colorado.

Stegosaurus has starred in a number of films and documentaries, and has often been shown fighting large carnivorous dinosaurs. Examples in which he a Ceratosaurus faces are Go back in time ( Journey to the Beginning of Time , 1954) and the documentary Dinosaurs conquer the world ( When Dinosaurs roamed America , 2001). Stegosaurus also fights against Tyrannosaurus on the screen, as in Planet der Monster ( Planet of Dinosaurs , 1977), Walt Disney's Fantasia (1940) and the new edition of the series Im Land der Saurier ( Land of the Lost , 1991/92).

Next appeared Stegosaurus in the classic monster movie King Kong (1933) and in The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997) and Jurassic World (2015) on. He was also in the multi-part television series Im Reich der Giganten ( Walking with Dinosaurs , 1999) and the special Die Geschichte von Big Al ( The Ballad of Big Al , 2000) to see.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Gregory S. Paul : The Princeton Field Guide To Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ et al. 2010, ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9 , pp. 224-226, online .

- ↑ a b Fernando Escaso, Francisco Ortega, Pedro Dantas, Elisabete Malafaia, Nuno L. Pimentel, Xabier Pereda-Suberbiola, José Luis Sanz, José Carlos Kullberg, María Carla Kullberg, Fernando Barriga: New Evidence of Shared Dinosaur Across Upper Jurassic Proto- North Atlantic: Stegosaurus From Portugal. In: The natural sciences . Vol. 94, No. 5, 2007, pp. 367-374, doi : 10.1007 / s00114-006-0209-8 .

- ↑ Peter M. Galton , Paul Upchurch : Stegosauria. In: David B. Weishampel , Peter Dodson , Halszka Osmólska (eds.): The Dinosauria . 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2004, ISBN 0-520-24209-2 , pp. 343-362, here p. 355.

- ↑ David Lambert: The ultimate dinosaur book. Dorling Kindersley in Association with Natural History Museum, London et al. 1993, ISBN 1-56458-304-X , pp. 110-129.

- ↑ a b c Kenneth Carpenter : Armor of Stegosaurus stenops, and the taphonomic history of a new specimen from Garden Park Colorado. In: The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. An interdisciplinary study. Denver Museum of Natural History, Denver, USA, May 26-28, 1994 (= Modern Geology. Vol. 22). Part 1. Gordon & Breach, New York NY et al. 1998, ISBN 90-5699-183-3 , pp. 127-144.

- ^ A b c d David E. Fastovsky , David B. Weishampel: Stegosauria: Hot Plates. David E. Fastovsky, David B. Weishampel: The Evolution and Extinction of the Dinosaurs. 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 2005, ISBN 0-521-81172-4 , pp. 107-130.

- ↑ Stegosaurus . University of Wyoming Geological Museum. October 8, 2006. University of Wyoming Geological Museum ( February 29, 2008 memento on Internet Archive )

- ↑ Kenneth Carpenter, Clifford A. Miles, Karen Cloward: New Primitive Stegosaur from the Morrison Formation, Wyoming. In: Kenneth Carpenter (Ed.): The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN 2001, ISBN 0-253-33964-2 , pp. 55-75.

- ↑ Jean Le Lœuff, Martin Lockley, Christian Meyer, Jean-Pierre Petit: Discovery of a thyreophoran trackway in the Hettangian of central France. In: Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences. Series 2, Fascicule A: Sciences de la Terre et des Planètes. Vol. 328, No. 3, 1999, ISSN 0764-4450 , pp. 215-219, doi : 10.1016 / S1251-8050 (99) 80099-8 .

- ^ A b Othniel C. Marsh : A new order of extinct Reptilia (Stegosauria) from the Jurassic of the Rocky Mountains. In: The American Journal of Science and Arts. Series 3, Vol. 14 = Vol. 114, No. 84, Article 52, 1877, ISSN 0002-9599 , pp. 513-514, digitized .

- ^ A b c Kenneth Carpenter, Peter M. Galton: Othniel Charles Marsh and the Eight-Spiked Stegosaurus. In: Kenneth Carpenter (Ed.): The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN 2001, ISBN 0-253-33964-2 , pp. 76-102.

- ^ A b Othniel C. Marsh: Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs, part IX. The skull and dermal armor of Stegosaurus. In: The American Journal of Science. Series 3, Vol. 34 = Vol. 134, No. 203, Article 45, 1887, pp. 413-417, digitized .

- ↑ Stegosaurus Marsh, 1877 (Dinosauria, Ornithischia): type species replaced with Stegosaurus stenops Marsh, 1887 , accessed on May 31, 2019.

- ^ Othniel C. Marsh: Notice of new Jurassic reptiles. In: The American Journal of Science and Arts. Series 3, Vol. 18 = Vol. 118, No. 108, Article 60, 1879, pp. 501-505, digitized .

- ↑ a b c d e f Peter M. Galton, Paul Upchurch: Stegosauria. In: David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, Halszka Osmólska (eds.): The Dinosauria . 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2004, ISBN 0-520-24209-2 , pp. 343-362, here p. 361.

- ^ Othniel C. Marsh: Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs, part V. In: The American Journal of Science. Series 3, Vol. 21 = Vol. 121, No. 75, Article 53, 1881, pp. 417-423, digitized .

- ^ A b c Robert T. Bakker : The Dinosaur Heresies. New Theories unlocking the Mystery of the Dinosaurs and their Extinction. William Morrow, New York NY 1986, ISBN 0-688-04287-2 .

- ^ A b c d e Charles Whitney Gilmore : Osteology of the armored Dinosauria in the United States National Museum, with special reference to the genus Stegosaurus (= Smithsonian Institution - United States National Museum. Bulletin. 89, ISSN 0362-9236 ). United States Government Printing Office, Washington DC 1914, digitized .

- ↑ a b c Susannah CR Maidment: Stegosauria: a historical review of the body fossil record and phylogenetic relationships. In: Swiss Journal of Geosciences. Vol. 103, No. 2 = Symposium on Stegosauria Proceedings , 2010, ISSN 1661-8726 , pp. 199-210, doi : 10.1007 / s00015-010-0023-3 .

- ↑ Peter Malcolm Galton: Craterosaurus pottonensis Seeley, a stegosaurian dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of England, and a review of Cretaceous stegosaurs. In: New Yearbook for Geology and Paleontology. Treatises. Vol. 161, No. 1, 1981, ISSN 0077-7749 , pp. 28-46.

- ↑ Hans-Dieter Sues : A Pachycephalosaurid Dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of Madagascar and Its Paleobiogeographical Implications. In: Journal of Paleontology. Vol. 54, No. 5, 1980, ISSN 0022-3360 , pp. 954-962, online on JSTOR .

- ↑ Gerard Gierliński, Karol Sabath: A probable stegosaurian track from the Late Jurassic of Poland. In: Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. Vol. 47, No. 3, 2002, ISSN 0567-7920 , pp. 561-564, online .

- ^ Martin Lockley, Meyer, Christian: Early Jurassic. Martin Lockley, Christian Meyer: Dinosaur tracks and other fossil footprints of Europe. Columbia University Press, New York NY 2000, ISBN 0-231-10710-2 , pp. 105-130, here p. 124.

- ^ A b Othniel C. Marsh: Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs, part III. In: The American Journal of Science. Series 3, Vol. 19 = Vol. 119, No. 111, Article 31, 1880, pp. 253-259, digitized .

- ^ A b Othniel C. Marsh: Restoration of Stegosaurus. In: The American Journal of Science. Series 3, Vol. 42 = Vol. 142, No. 248, Article 16, 1891, pp. 179-181, digitized .

- ↑ Emily B. Giffin: Gross spinal anatomy and limb use in living and fossil reptiles. In: Paleobiology. Vol. 16, No. 4, 1990, ISSN 0094-8373 , pp. 448-458.

- ^ Edwin H. Colbert : Dinosaurs. Their Discovery and their World. Hutchinson, London 1962, pp. 82-99.

- ↑ a b Лео Шйович Давиташвили: Теория полового отбора. Изд-во Академии наук СССР, Москва 1961.

- ↑ a b Vivian de Buffrénil, James O. Farlow, Armand J. de Ricqlès: Growth and Function of Stegosaurus Plates; Evidence from Bone Histology Paleobiology. In: Paleobiology. Vol. 12, No. 4, 1986, pp. 459-473.

- ↑ James O. Farlow, Carl V. Thompson, Daniel E. Rosner: Plates of the Dinosaur Stegosaurus: Forced Convection Heat Loss Fins? In: Science . Vol. 192, No. 4244, 1976, pp. 1123-1125, doi : 10.1126 / science.192.4244.1123 .

- ↑ Russell P. Main, Kevin Padian , John R. Horner : Comparative histology, growth and evolution of archosaurian osteoderms: why did Stegosaurus have such large dorsal plates? In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Supplement to Vol. 3 = Abstracts of Papers, Sixtieth Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, Fiesta Americana Reforma Hotel, Mexico City, Mexico, October 25-28, 2000 , 2000, ISSN 0272-4634 , p. 56A.

- ^ Robert T. Bakker: The Dinosaur Heresies. New Theories unlocking the Mystery of the Dinosaurs and their Extinction. William Morrow, New York NY 1986, ISBN 0-688-04287-2 , pp. 229-234.

- ↑ Hillary Mayell: Stegosaur plates used for identification. In: National Geographic News , May 25, 2005, accessed September 21, 2014.

- ↑ Lorrie A. McWhinney, Bruce M. Rothschild, Kenneth Carpenter: Posttraumatic Chronic Osteomyelitis in Stegosaurus dermal spikes. In: Kenneth Carpenter (Ed.): The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN 2001, ISBN 0-253-33964-2 , pp. 141-156.

- ↑ Kenneth Carpenter, Frank Sanders, Lorrie A. McWhiiney, Lowell Wood: Evidence for Predator-Prey Relationships: Example for Allosaurus and Stegosaurus. In: Kenneth Carpenter (Ed.): The Carnivorous Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN et al. 2005, ISBN 0-253-34539-1 , pp. 325-350.

- ↑ Stegosaurus ungulatus ( Memento of 29 May 2008 at the Internet Archive ) Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ^ Stegosaurs ( Memento June 26, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Jacobson, RJ. Dinosaur and Vertebrate Paleontology Information. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ^ David B. Weishampel: Interactions between Mesozoic Plants and Vertebrates: Fructifications and seed predation. In: New Yearbook for Geology and Paleontology. Treatises. Vol. 167, 1984, pp. 224-250.

- ^ Colorado Department of Personnel website - State emblems