drum brake

1 wheel brake cylinder

2 lower support (counter bearing)

3 brake shoes (left and right)

4 brake lining

5 wheel hub with five internal threads for wheel bolts

6 adjusting wedge

7 retraction

springs (top and bottom) 8 spring plate with spring and retaining bolt

9 dust caps of the wheel brake cylinder

Drum brakes are friction brakes in which brake linings act on a cylindrical surface (the drum). When the brake is actuated, the brake lining is usually pressed from the inside against the rotating drum. In motor vehicles , drum brakes have been replaced by disc brakes . In less powerful cars, they are still used on the rear axle; The drum brake is still the state of the art for heavy commercial vehicles and trailers.

In the rotating brake drum, the two brake shoes, which are movably mounted on the brake anchor plate, are pressed on from the inside . This is done mechanically via a camshaft , an expanding wedge or a wheel brake cylinder .

history

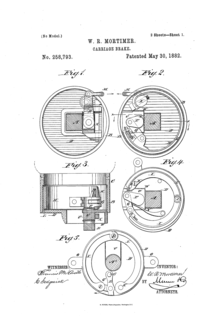

The development of the drum brake was influenced by the outer band brake . Walter Russell Mortimer received his first patent for an inner-shoe drum brake for bicycles in 1881. Drum brakes were first used in an automobile in 1900 on the rear wheels of the 35 hp Mercedes , a design by Wilhelm Maybach . The brake pads were water-cooled.

"Maybach evidently had neither the drum brakes nor the water cooling patented, so that the drum brakes quickly became established in the automotive industry."

In 1902, Louis Renault applied for patents on various types of internal shoe brakes and finally adopted the Simplex brake in series production. When motorcycle the inside shoe brake was only in the 1920s with the prior art.

advantages

- Due to the internal reinforcement, only relatively low operating forces are required. The measure for the internal reinforcement is the brake parameter C *. Depending on the design, it is between two and five times the coefficient of friction µ. This means that a brake booster can be dispensed with in light vehicles .

- The closed design protects the brake shoes from coarse particles. This is why drum brakes are still predominantly used in current off-road vehicles and construction site trucks .

- The inwardly directed gap between the anchor plate and the brake drum means that less abrasion (brake dust) settles on the rim.

- Drum brakes are more durable than disc brakes. Some maintenance manuals only provide for checking and removing the brake drum to remove abrasion and rust in a longer maintenance interval, and renewing the brake shoes and small parts at double intervals.

disadvantage

- With drum brakes, changing the brake linings is more complex than with disc brakes .

- Drum brakes are more sensitive to fluctuations in the coefficient of friction compared to disc brakes. In the passenger cars with drum brakes on the front axle, which were common up until the 1970s, this often led to the vehicle pulling sideways or breaking away when braking.

- With the same braking performance, a drum brake is heavier than a corresponding disc brake in a truck.

- Heat dissipation from heavily loaded brakes is comparatively poor.

- Characteristic value fluctuations ( fading ) occur with high thermal loads .

Types

Simplex brake

The simplex brake is the simplest and most widely used type of drum brake. It can be found in everything from bicycles to heavy trucks. It has a running brake shoe and a running brake shoe. This means that the braking effect is the same in both forward and reverse travel. The brake shoes are spread by a central wheel cylinder, while the brake shoes are mounted around a pivot on the other side. In the case of heavy trucks and trailers, actuation is via an S-cam. The small version of the simplex brake can be found as a parking brake in many cars . The brake parameter C * is 2.0.

There are 3 versions with different structures.

- cylinder

- The brake shoes are actuated via a cylinder (wheel brake cylinder). This is controlled hydraulically and generates equally large forces in both directions. This actuation is mainly used in cars and light vans.

- S-cam

- The brake shoes are actuated via an S-cam. This sits on the brake camshaft, which is rotated by a slack adjuster. The cam, which is controlled from the outside with a compressed air brake cylinder, and the fixed clamping result in approximately the same wear of the lining on the upper and lower jaws. It is used in commercial vehicles .

- external cylinder

- In the variant, a valve is controlled by an external compressed air or hydraulic cylinder. This piston, moved by the cylinder, spreads the two brake shoes. This type is mainly used in light to medium-weight commercial vehicles with compressed air brakes.

In any case, the following applies to the simplex brake: Due to the direction of rotation of the brake drum, the clamping force of a brake shoe is increased by the friction force.

Duplex brake

→ Main article: Duplex brake

With the duplex brake, each brake shoe has its own actuating device on one side. As a result, both jaws open up and are therefore self-reinforcing. The brake parameter C * is 3.0 when driving forward and is significantly lower when driving backwards. The advantage over the simplex brake is an approx. 50% higher braking effect with the same actuation force. Their disadvantage is the greater production and maintenance costs and the fact that the braking effect is significantly lower when reversing. Before the general introduction of disc brakes, duplex brakes were mainly used on the front axle of heavy passenger cars and light commercial vehicles, as well as on motorcycles .

Duo-duplex brake

In contrast to the duplex brake, the duo-duplex brake has two double-acting wheel cylinders instead of two single-acting wheel cylinders. This results in a higher contact pressure of the brake shoes, but the self-reinforcement through rotation is dispensed with. It has the same effect when driving forwards and backwards. This elaborate design has hardly been used since the 1960s. The brake parameter C * is 3.0 for forward and reverse travel.

Servo brake

The servo brake has the highest internal gain. Like the simplex brake, it has a wheel cylinder, but the brake shoes are floating at the lower pivot point. The supporting force of the primary jaw (running up) is transferred to the secondary jaw (running down) by a pressure bolt and self-reinforcement is produced in both brake shoes in one direction of travel. There is no self-reinforcement when reversing.

This results in a very large difference in the braking effect between forward and reverse travel. Due to the high internal reinforcement of the servo brake, it requires the lowest actuation forces, but it is difficult to dose and very sensitive to fluctuations in the friction coefficient of the brake linings. The brake parameter C * is 5.0 when driving forward and is significantly lower when driving backwards.

Duo servo brake

The duo servo brake is initially identical to the servo brake. The disadvantage of the inadequate braking effect when reversing is compensated for by the fact that the pressure pin can be supported on a bearing depending on the direction of movement. This results in two running (self-energizing) brake shoes in both directions.

It is used in light and medium-weight trucks and as a parking brake (cup disk) in cars with four brake disks (flanged to the wheel carrier together with the disk brake on the rear axle). The brake parameter C * is 5.0 for forward and reverse travel. This is the highest possible self-reinforcement.

3-shoe drum brake

In the mid-1960s, Alfa Romeo had drum brakes with three approaching shoes in the 101 (Giulia Spider, Sprint, Sprint Speciale) and 105 (Giulia 1st series) models on the front axle.

Each of the three brake shoes is actuated by its own brake cylinder.

External shoe brake

Drum brakes are also available in the reverse arrangement: their brake shoes slide on a drum from the outside. These drum brakes can be found nowadays in mechanical engineering, especially in conveyor technology for braking conveyor machines, e.g. B. in mining, elevator and marine engineering, and are usually attached to the input or output shaft of gearboxes . This type of drum brake was also common in automobiles in the 1920s, as a brake on the gearbox or on the cardan shaft, and thus indirectly braked the rear axle via the axle drive, without the need for special wheel brakes. This system was also used as a parking brake for a long time. They were also often used in railcar construction in the 1930s. Here there were the application forms of external shoe brakes ( DR standard railcars ) or internal shoe brakes ( ČSD M 260.001 ). The maximum speed of the vehicles equipped with these brakes was only permitted for 90 km / h, so that their area of application was limited to use on branch lines or in suburban traffic .

literature

- Bert Breuer, Karlheinz H. Bill: Brake manual: Fundamentals, components, systems, driving dynamics. Vieweg + Teubner, Wiesbaden 2006, ISBN 978-3-8348-0064-0 .

- MAN Nutzfahrzeuge Group: Basics of commercial vehicle technology. Basic knowledge of trucks and buses; Marketing training. Kirschbaum Verlag, Bonn 2004, ISBN 3-7812-1640-3 .

Web links

- ChrisFix: Repairing the drum brake (English), YouTube from December 27, 2016

Individual evidence

- ^ Tony Hadland, Hans-Erhard Lessing: Bicycle Design. An Illustrated History. MIT Press, Cambridge / London 2014, ISBN 978-0-262-02675-8 , pp. 285 ff.

- ↑ British Patent No. 3279, July 26, 1881; French Patent No. 134967 issued January 20, 1882; U.S. Patent No. 258793, dated May 30, 1882 ( online at Google Patents).

- ↑ Olaf von Fersen (ed.): A century of automobile technology. Passenger cars. VDI Verlag, 1986, ISBN 3-18-400620-4 , p. 398.

- ↑ a b Olaf von Fersen (Ed.): A century of automobile technology. Passenger cars. VDI Verlag, 1986, ISBN 3-18-400620-4 , p. 400.

- ^ Peter Witt: Motorcycles. 1st edition. Verlag Technik, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-341-00657-5 , p. 45.

- ^ Peter Steinfurth, Michael Herbold: Zeitschrift Oldtimer-Markt 7/1995, p. 19.

- ↑ Heinz Kurz: The railcars of the Reichsbahn types. EK-Verlag, Freiburg 1988, ISBN 3-88255-803-2 , p. 300.