Chytridiomycosis

The Chytridiomykose is a fungal disease ( mycosis ) in amphibians. The pathogens are the chytrid fungus ( Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis ) and Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans . At the end of 1998 it was discussed for the first time in connection with the global amphibian decline ( Global Amphibian Decline ), but this is controversial as a monocausal cause.

Disease emergence

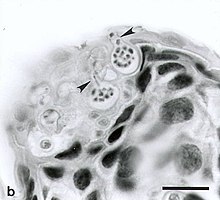

The pathogenesis is not yet fully understood. It is probably a strong impairment of the biological functions of the outer skin, the gas, liquid and mineral metabolism as well as the production and release of skin secretions, so that the protective function is no longer given.

The development of the sporangia is a sign of the cellular maturation of the pathogen. Hyperkeratosis can result from a hyperplastic reaction as a result of an increased turnover of epidermal cells and premature cornification and cell death of infected cells .

An impairment of the immune system due to various, mostly environmental stress factors or primary diseases is considered to be beneficial for a Chytridiomycete infection. This could be among others:

- Sub-optimal climatic and environmental conditions (humidity, fresh air, temperature, light quality and light quantity)

- Stress due to rapid climatic changes

- Unbalanced and one-sided diet

- Stress from an incorrectly composed community in the terrarium

- Sudden change from dry season to rainy season

- Sudden changes in the frog's habitat, e.g. B. a conversion of the facility or a relocation of the animal.

- Stressful situations for the animal e.g. B. improper transport, malnutrition etc.

- Primary diseases (e.g. worms, pseudomonads etc.)

Occurrence

The disease presumably originates from Africa and was first detected retrospectively in a clawed frog from 1938. Chytridiomycosis was then a stable endemic in South Africa and was probably spread worldwide through the trade in clawed frogs. Around 500 amphibian species in over 60 countries are affected by the disease.

After the pathogen became known in amphibians living in the wild and kept in human care in Australia, North, Central and South America, infections are described for the first time that were detected in terrarium animals in Germany and the Netherlands. Imported poison dart frogs ( D. auratus , D. pumilio ) from Costa Rica and Phyllobates vittatus from French Guiana died of chytridiomycosis within a week of arriving in Europe. Batrachochytrium has also been isolated from frogs that can be shown to have come from offspring in terrariums (Germany, Belgium). Due to the infestation and disease of animals that can be proven to have come from offspring in terrariums, it can still be assumed that the pathogen is latently ubiquitous in amphibians that are kept in human care . Small amounts of pathogen could also be detected in healthy frogs and tadpoles without an outbreak of disease.

The pathogen has now also been detected in almost all amphibian species in Europe. Studies between 2003 and 2010 showed a prevalence of 7.5 percent in around 3,000 tested individuals in Germany. Unlike in Australia and America, the infection in European amphibians seems to break out relatively rarely and usually does not take a dramatic course.

The fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans attacks fire salamanders in north-western Europe - mainly in the Netherlands - which are affected despite their skin toxins. In the Netherlands there has been a drop in stocks of up to 96% since 2010. The fungal infection often leads to death of the amphibian after just seven days.

Symptoms

Chytridiomycosis manifests itself in loss of appetite up to refusal to eat, apathy , restricted movement, ataxia , prolonged stay in the water and ultimately death of the animal.

Skin changes only occur in some of the cases. The skin then appears dull, reddened, with whitish coatings and darkening of the skin color and the drawing patterns.

Diagnosis

The pathogen detection is very simple after the onset of death and on the basis of biopsies , a histological examination is carried out after hematoxylin-eosin staining .

Diagnosis is more difficult after contact or scratch-off tests using PCR . This enables detection of massive infestation in particular. The finding should only be considered positive if sporangia are detected at the same time .

In the meantime, an accurate method has been developed to detect the fungus both qualitatively and quantitatively using real-time PCR .

therapy

Sick animals or animals at risk of infection with antimycotic z. B. Treat itraconazole as a 10 minute bath daily for 7-10 days. Terrariums must be thoroughly cleaned and disinfected (e.g. with benzalkonium chloride or other fungicidal disinfectants, through heat, dryness or 70% ethanol).

Chloramphenicol , a broad-spectrum antibiotic, has also proven to be an effective means of treating even severely infected animals, as New Zealand scientists were able to demonstrate in their studies on Litoria ewingii and Litoria raniformis .

Batrachochytrium dendrobatitis does not survive dehydration. In order to prevent this fungus from spreading, material that comes into contact with water, such as water sports or fishing equipment, must be dried completely. The trade in animals and plants from affected waters as well as their movement and the subsequent contact with local fauna also represent a great risk for B. dendrobatitis- free regions and their amphibians.

literature

- F. Mutschmann and others: Chytridiomycosis in amphibians - first evidence in Europe. In: Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 2000 Oct; 113 (10), pp. 380-383. PMID 11084755 ( PDF ( Memento from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ))

Individual evidence

- ↑ Berger et al .: Chytridiomycosis causes amphibian mortality associated with population declines in the rain forests of Australia and Central America. In: Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 1998 Jul 21; 95 (15), pp. 9031-9036. PMID 9671799 .

- ^ I. Di Rosa et al.: Ecology: the proximate cause of frog declines? In: Nature . 2007 May 31; 447 (7144), pp. E4-E5 PMID 17538572

- ^ RA Alford et al.: Ecology: Global warming and amphibian losses. In: Nature. 2007 May 31; 447 (7144), pp. E3-E4 PMID 17538571

- ↑ L. Berger et al: Life cycle stages of the amphibian chytrid Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. In: Dis Aquat Organ. 2005 Dec 30; 68 (1), pp. 51-63. PMID 16465834

- ↑ C. Weldon et al .: Origin of the amphibian chytrid fungus. In: Emerg Infect Dis . 2004 Dec; 10 (12), pp. 2100-2105. PMID 15663845

- ↑ Fungal disease causes mass deaths in frogs. In: tagesanzeiger.ch . April 12, 2019, accessed April 26, 2019 .

- ↑ Torsten Ohst, Yvonne Gräser, Frank Mutschmann , Jörg Plötner: New findings on the endangerment of European amphibians by the skin fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. In: Journal of Field Herpetology. 18, Laurenti-Verlag, Bielefeld 2011, pp. 1–17.

- ^ Daniel Lingenhöhl: Aggressive fungus threatens fire salamanders. Report at Spektrum.de from September 2, 2013.

- ↑ To Martel, Annemarieke Spitzen-van der Sluijs, Mark Blooi and others: Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans sp. nov. causes lethal chytridiomycosis in amphibians. In: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013. doi: 10.1073 / pnas.1307356110 (free full text access).

- ↑ RW Retallick et al: A non-lethal technique for detecting the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis on tadpoles. In: Dis Aquat Organ. 2006 Sep 14; 72 (1), pp. 77-85. PMID 17067076

- ↑ DG Boyle et al: Rapid quantitative detection of chytridiomycosis (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) in amphibian samples using real-time Taqman PCR assay. In: Dis Aquat Organ. 2004 Aug 1; 60 (2), pp. 141-148.

- ^ ML Johnson et al .: Fungicidal effects of chemical disinfectants, UV light, desiccation and heat on the amphibian chytrid Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. In: Dis Aquat Organ. 2003 Dec 29; 57 (3), pp. 255-260. PMID 14960039

- ↑ S. Young, R. Speare, L. Berger, LF Skerratt: Chloramphenicol with fluid and electrolyte therapy cures terminally ill green tree frogs (Litoria caerulea) with chytridiomycosis. In: Journal of zoo and wildlife medicine: official publication of the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians. Volume 43, number 2, June 2012, pp. 330-337, doi : 10.1638 / 2011-0231.1 , PMID 22779237 .