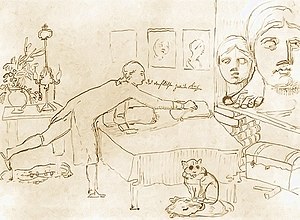

The damn second pillow

|

| The damn second pillow |

|---|

| Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein , 1787 |

| Ink drawing |

| 19.7 x 26.9 cm |

| Weimar Classic Foundation |

The cursed second pillow is the subject of a drawing by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein , which he made in Rome in 1787 . It shows Johann Wolfgang Goethe in his quarters in Via del Corso No. 18–20, now known as Casa di Goethe . Goethe lived there during his first stay in Rome from autumn 1786 to February 1787 and later again after his return from the south of the country in 1787.

The drawing was in Goethe's possession. When the poet sorted and cataloged the Tischbein drawings he had brought with him from Italy in 1821, he classified them as No. 11 in the folder “Common Life” and referred to them quite neutrally as “Rondanini apartment above”. In a letter to Tischbein dated April 21, 1821, however, he mentioned "the devilish second pillow" and also "the Roman jokes" to which this drawing belongs.

description

The drawing, executed in brown ink, is landscape format. Goethe stands on his right leg, bent over a wide bed, on which he leans with his left hand, and stretches to grab the second pillow or perhaps to put it in its right place. He has stretched his left leg backwards for balance, and the slipper can barely hold onto the raised left foot. Goethe's head can be seen in profile, in front of his mouth is the annoying phrase “The cursed second pillow” - written in Tischbein's notation with ü and ß. Goethe's hair is plaited in a braid, he wears a long skirt, knee breeches and probably stockings. The supporting leg, the thigh of which should actually not be visible behind the skirt, is drawn out hinted at, and there are also lines in other parts of the drawing that would not be visible behind objects or objects. The movement of the poet's right hand is indicated by several arched pen strokes. The bed, on which a kind of bedspread appears to be lying, has its foot end facing the viewer and is drawn in perspective. On the left, behind Goethe's stretched out left leg, there is a simple table on which a bouquet is arranged in a vase and a two-flame candlestick is burning. Underneath is probably a coat bag or a similar piece of luggage. Three pictures are indicated above the head of the bed. While the left only appears like an empty frame, two heads can be seen in the other two pictures, possibly a male and a female portrait. The contents of the improvised shelf on the right-hand side of the room, on the other hand, are detailed. A thick board rests on several extensive books and carries three monumental plaster casts: two busts with a bare left foot in between. According to Wolfgang von Oettingen , one of the busts is “the mask of Juno Ludovisi , which Goethe bought on January 5, 1787, so not the head that was later donated by State Councilor Schultz in Weimar [...] The other head is the one on January 13 mentioned “smaller and lesser” Juno. ”But there were no fewer than three Juno heads in Goethe's room. When Goethe and Tischbein left Rome in February 1787, Goethe concluded his report on the stay in the Eternal City with the sentence: "There are now three Junons standing next to each other for comparison, and we leave them as if there were none."

The authors and titles of the books are indicated by a few letters, apparently among others works by Johann Joachim Winckelmann , perhaps in the Italian translation by Carlo Fea , which Goethe bought in Rome, and Titus Livius . There is also a chest with a domed lid under the shelf and a geologist's hammer lies on the floor in front of the shelf .

In the foreground, in front of the foot of the bed, there seems to be a fur with an animal head on the floor, on which another animal is sitting and looking at the viewer from two differently colored eyes. The fur used as a bedside rug could come from a wolf and thus indicate the Eternal City, the seated animal is generally interpreted as a cat, which is supported by the posture, but not necessarily the size and shape of the head, which is more like monkey or something like a half-ape. Oettingen, however, writes: “The cat, which according to the landlady adored Juno, is not missing.” With that, however, he gives the mention of this episode in the Italian trip back inaccurately: On the date of December 25, 1787, Goethe reports there: “I I could not refrain from buying the colossal head of a Jupiter . He stands across from my bed, well lit [...] Our old landlady usually sneaks after her familiar cat when she comes in to make the bed. I sat in the large hall and heard the woman doing her business inside. Suddenly, very quickly and violently against her habit, she opens the door and calls me to come hurry and see a miracle. When I asked what it was, she replied that the cat worships God the Father [...] The bust stands on a high foot and the body is cut off well below the chest so that the head sticks out . Now the cat had jumped on the table, had put its paws on the god's chest, and reached with its snout, stretching its limbs as much as possible, up to the holy beard, which it licked with the greatest delicacy [... ] “Goethe let the old woman believe in miracles, but explained the animal's behavior by the fact that it licked out the fat residues that had remained in the depressions of the plaster of paris beard after the casting.

Especially in the depiction of this animal, the overlapping of the outlines with those of the objects behind them becomes apparent. Both the puckered, drooping edge of the bedspread and the alleged wolf skin can be seen through the body of the seated creature.

backgrounds

Tired of court life and driven by a burning longing for Italy, Goethe set off from Karlsbad on September 3, 1786 at three in the morning in a stagecoach to travel incognito to Italy. He used the code name "Johann Philipp Möller", which on the way also temporarily became "Müller" or "Miller" and, intentionally, a Russian-sounding variant of this name with an -off attached. A sophisticated system for receiving mail and money should ensure that he did not have to reveal his identity and that his travel route and destination were not known for the first few weeks. In this first phase, his secretary and servant Philipp Seidel was responsible for forwarding letters . Although Goethe was in correspondence with Carl August von Sachsen-Weimar , Charlotte von Stein and other people at home in this way and was immediately recognized in Rome, where he B. In the circles around the painter Angelika Kauffmann , his desire to break out of the usual social constraints and lead a simple life was largely respected, even if he was under observation: Cardinal Franz Herzan , imperial ambassador in Rome, provided care the Austrian State Chancellor Kaunitz with reports on Goethe. He relied on the embassy secretary Franz Eberle, who claimed to have met Goethe in an osteria and talked to him confidentially, but probably obtained his knowledge from Tischbein.

Carl August von Sachsen-Weimar granted Goethe a generous vacation after he had disappeared from Karlsbad and reported by letter, so that he could spend a lot of time in Italy, but there he was also able to prepare the second half of his eight-volume edition, which he was preparing had concluded a contract with the publisher Göschen on departure . The Duke approved him in several stages to extend his vacation until Easter 1788 and also increased his salary from 1,600 thalers to 1,800 thalers.

Goethe arrived in Rome on October 29, 1786 and, like most journeys from the north, entered the city through the Porta del Popolo , two days after Karl Philipp Moritz arrived there, with whom he became friends in Rome. At first he apparently stayed in an inn, probably in the Locanda dell 'Orso, and hired a servant, but soon after his arrival he made contact with Tischbein, who had been living in Rome for three years on a scholarship . At that time he did not know the painter personally, but had been in contact by letter for a long time. Tischbein offered to move into his guest room, which Goethe evidently made use of after the first night in the inn. This room is likely to be shown in Tischbein's drawing and was inhabited by Goethe first until his departure for Naples on February 22, 1787 and then again after his return in June 1787.

Tischbein had rented a room from the couple Sante Serafino Collina and Piera Giovanna de Rossi. Collina, a former coachman and already over 70 years old, lived together with his wife by subletting various rooms and catering for the guests. In addition to Tischbein, who ceded one of his three rooms to Goethe, Johann Georg Schütz and Friedrich Bury also lived in the apartment on the first floor of Casa Moscatelli. Goethe had close contact with Tischbein in particular during his first few months in Rome. In addition to the drawing with the bed, other representations from this phase of life have been preserved, on which Tischbein his roommate z. B. at the window of his room and reading while swaying on a chair, the well-known depiction of the two happy men in extremely casual posture on a sofa should come from this time.

The conditions in the Casa Moscatelli were rather simple; among other things, Goethe's room could not be heated. Between November 1786 and January 1787 he visited a tailor five times. In a letter to Fritz von Stein on January 4, 1787, he reported that he wore the resulting white cloak, in which he can be seen in Tischbein's painting Goethe in the Campagna , at home in order to be able to protect himself from the cold .

Dating and interpretation of the drawing

One could assume that the drawing and especially the saying “The cursed second pillow” alludes to the difficulties of a Central European tourist to reconcile with the sleeping habits and the equipment of the sleeping accommodation in the foreign country. The fact that a second pillow is available, but only one person is walking in the bedroom, could also be interpreted to mean that the owner of the bed was actually hoping for togetherness and was disappointed.

Roberto Zapperi goes one step further and develops a theory on a very specific background of the drawing and claims that Tischbein committed a little malice here and that Goethe later deliberately left a trace in the wrong direction. The poet claimed to have been inspired to his 15th elegy and to the figure of Faustina in the Osteria alla Campana, where a young girl wrote the time for a rendezvous on the tabletop with spilled wine. Zapperi considers this to be fiction and the re-use of an ancient topos for various reasons: the Roman women in Goethe's time were mostly illiterate and, according to contemporary witnesses, tablecloths were normally on the tables. According to the notes in his edition booklet, Goethe frequented Vinzenz Roesler's osteria in strada Condotti, like many other German artists in Rome, and did so particularly eagerly in January 1787. This Roesler had numerous children, including Costanza and Maria Elisabetta, about fourteen years old. Zapperi assumes that of the three portraits of female models that Tischbein created in Rome around 1787, two represent the two Roesler daughters. And Goethe brought these two pictures home with him from his trip to Italy. There was also an undated letter in his estate, apparently written by a professional scribe on behalf of an illiterate woman. The girl informed the recipient that a fan had been given to him, but had been removed again immediately. The addressee should please give him a new fan. The name given under this letter is "Costanza Releir", and Zapperi concludes from this that it was Costanza Roesler, whose name the Italian writer was unable to reproduce correctly and who made advances to Goethe with this request for a fan. However, as a strictly moral Roman girl, she did not think of a short relationship, but of a marriage, which again was not in Goethe's sense. Obviously Goethe did not buy a fan, but gave Costanza a piece of jewelry before he left for Naples. According to Zapperi, Goethe had "had many illusions about the girl's willingness to get involved with him," but the coquetry of the landlord's daughter was misleading and she was not ready to "go to bed with a guest of her father". After there was “nothing more to get” in Rome, “nothing more stood in the way” of leaving for Naples or he “got out of the dust”. A few months later, Costanza Roesler married the waiter Antonio Gentile, with whom she had many children.

During the trip to Naples there was a falling out between Goethe and Tischbein, who had initially accompanied him but did not want to go to Sicily. Goethe found Tischbein again in the old apartment after his return to Rome, but the coexistence there did not last long, as the painter moved to Naples a few weeks later for several years. Goethe then took over a larger room from Tischbein. It is quite likely that the drawing with the bed was created during the first phase of living together in Rome. Zapperi explains: “The terminus post quem is provided by the Livius volume, which Goethe acquired on January 17th, the terminus ante quem Goethe's departure for Naples on February 22nd, 1787 [...] during the time when Goethe Costanza took over the court made. In view of the fiasco with which the story ended, the drawing seems to comment on the dream of a night of love that ruined the girl's refusal: it looks as if Goethe [...] angry about this after the girl's refusal He would have run back home sluggishly. "Although Goethe later generously described this graphic comment on his defeat in love as a joke, it was a" very bad joke of decidedly bad taste "and the picture speaks of envy and malice of the shy table leg towards him popular Goethe.

In his novel Rom, Villa Massimo, Hanns-Josef Ortheil lets the protagonist Peter Ka pay a visit to the Casa di Goethe towards the end of his fellowship. Ka, a lyric poet, feels deeply moved by the parallels between Goethe's “time out” in Rome and his own stay at Villa Massimo. He looks very carefully at the Tischbein sketches, especially the one with the accursed second pillow and the depiction of Goethe standing at the window and comes to the conclusion: “Goethe, who has lived beyond the ages, is much more present in the small sketches. And in the incomparable watercolor. Recordings of seconds of happiness. His entire stay in Rome, captured with a few lines. ”Unlike Zapperi, the fictional character Ka sees no anger in the rapid movement of the man who leans over the bed and reaches for the pillow and is in doubt whether Goethe is about to position or remove the pillow. Ka also thinks it is possible that a positive love experience took place here: “Ultimately, this apartment on the Corso was probably also the historical primordial cell of the later major project of the Deutsche Akademie Villa Massimo . A poet, several artists, a musician - all together in one apartment, many evenings together in (well, the ugly word has to come out :) "interdisciplinary" conversation. And late at night the Roman lover sneaks up the steps. And stays until the early morning. While the cat is slumbering in front of the bed. And the double bed creaks violently. ”Returning to his hometown Wuppertal , this Peter Ka begins to write Roman elegies based on the example of Goethe. Finally he returns to Rome and takes up residence there, in a similarly sparse furnished room as it was once Goethe's room with the bed with two pillows.

literature

- Roberto Zapperi: The Incognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3

Individual evidence

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 160

- ↑ Quoted from Robert Zapperi, Das Inkognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 161.

- ↑ a b Wolfgang von Oettingen, Goethe and Tischbein , Weimar 1910 (= writings of the Goethe Society 25), p. 36

- ↑ Goethe mentioned the larger Juno cast in a letter to Charlotte von Stein dated January 6, 1787 and both Juno portraits in a letter to Herder dated January 13 of the same year. At least one of the Juno portraits later became the property of Angelika Kauffmann. See Jutta Assel and Georg Jäger, Goethe's Juno on www.goethezeitportal.de

- ^ Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Italienische Reise , Insel Verlag Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig 1976, ISBN 978-3-458-31875-0 , p. 231

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's very different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 162

- ^ Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Italienische Reise , Insel Verlag Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig 1976, ISBN 978-3-458-31875-0 , pp. 199 f.

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 161 ff .; an illustration can be found on p. 160.

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 7

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 111

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 73 f.

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 21

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 27

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 35

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 52

- ↑ See Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Italienische Reise , Insel Verlag Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig 1976, ISBN 978-3-458-31875-0 , p. 208: On January 13, 1787 he noted that in the cold of these days “ is better everywhere than in the rooms which, without a stove and fireplace, only receive us to sleep or to feel uncomfortable. ”In order to be able to write more extensively, he sat down for example. B. on February 16 “in the anteroom by the fireplace” to use the warmth of a “well-fed fire this time”, see p. ibid p. 222, and also on December 25 of the previous year he had been sitting “in the large hall” when the landlady informed him about the cat's strange behavior, see p. ibid, p. 200. From the note dated November 15, 1786, which is, however, under the indication of the place Frascati , it can be seen that the circle around Tischbein and Goethe in the evening revolved around a large, round table on which a three-armed brass lamp stood and who was probably also in a larger and heatable room, used to gather, see p. ibid p. 181.

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 97

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 135 ff.

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , pp. 140 ff.

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's very different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 155

- ↑ a b c Robert Zapperi, Das Inkognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 156

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 159

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 123

- ↑ Robert Zapperi, The Incognito. Goethe's completely different existence in Rome , Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60471-3 , p. 163

- ↑ Hanns-Josef Ortheil, Rome, Villa Massimo , Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-442-71427-8 , p. 232

- ↑ Hanns-Josef Ortheil, Rome, Villa Massimo , Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-442-71427-8 , p. 229

- ↑ Hanns-Josef Ortheil, Rome, Villa Massimo , Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-442-71427-8 , p. 232