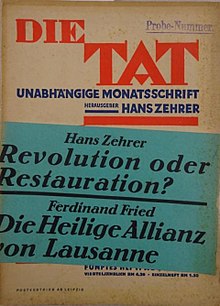

Die Tat (monthly magazine)

The act was a German monthly magazine for politics and culture . It was founded in April 1909 and was published until 1938 in the publishing of Eugen Diederichs in Jena . From 1939 to 1944 it was published under the title Das XX. Century continued. The magazine was subject to different ideological currents in the individual phases of its existence .

The act as a "free religious" organ (1909–1912)

The magazine was founded in April 1909 by the writer Ernst Horneffer and his brother August . Horneffer, who at that time was head of the Monistenbund, a free religious group in Leipzig, put the new magazine in the service of his philosophical worldview in its subtitle - Paths to Free Humanity . In terms of content, the act in this first phase was mainly focused on cultural and humanities topics. One intention of the early deed was to bridge the “disastrous dichotomy” that Horneffer saw between the inner and outer man. Horneffer formulated the programmatic goal of the magazine: “To restore the unity of content and form, of internal character and external appearance in our culture.” Horneff understood the name of the magazine as a call to put the said unity into practice: “That is why we provide at its top the strict warning: 'The deed' as what we lack, what we are looking for. "

In addition to his brother, Horneffer gained the Bonn philosopher Johannes Verweyen, the poet Ernst Schnabel , the literary historian Samuel Lublinski and Karl Hoffmann as employees . The publishing success of “Der Tat” was low in this phase. As an organ of free religious circles, and less as a cultural-political magazine, it did not succeed in attracting more than a thousand subscribers.

Life reformist (1912-1918)

In October 1912, the Jena publisher Eugen Diederichs took over the paper, whose circulation at that time was only a loss-making 1000 copies. The content was realigned, which was expressed in the new subtitle A social-religious monthly . Diederichs formulated his goal: "A cultural magazine should be made out of the act that goes beyond its previous religious-ethical basis."

A little later, the subtitle was expanded to become a social-religious monthly for German culture . Since Horneffer's conception of a sheet of Freemasonry and Diederichs' idea of a magazine that was to be both a platform for his publishing authors and a mouthpiece for new ideas from people and state did not go well with one another, Horneffer left the act in April 1916 In the same month Diederichs became the sole editor. The magazine was now called Die Tat until further notice . Monthly for the future of German culture , Diederichs' aim was to turn the monthly into a “forum for future culture”.

Under the influence of German idealism and a deepening of national sentiment along the lines of Lagarde , Eugen Diederichs directed and shaped the act for the next decade and made it a forum for his personal ideas of a national people on a religious basis, of a German people's state, national mysticism and radical anti-liberalism. The act was not a national journal in the style of the “primitive” national groups of the Weimar period, but was more demanding, esoteric and cultivated than the latter. Kurt Sontheimer assumed an anti-liberal, anti-human, anti-civilizing and anti-western affect.

Educated middle class (1918–1929)

After the First World War , the paper was characterized by a “program lack of a program” (Hanke / Hübinger ), but it set special accents on the subjects of “education”, “religion” and “people”.

By 1927 at the latest, the paper fell into a serious crisis, which was reflected in the falling number of subscribers. The criticism of Diederichs' conception grew stronger, and the young readers that Diederichs wanted to address demanded concrete goals and not abstract central ideas.

In 1928 Diederichs handed over the editing to the Germanist Adam Kuckhoff , in whom he believed he had found the man who could lead the younger generation to the act. However, Kuckhoff steered, supported by the theologian Heinrich Getzeny , a course "against romanticism", which Diederichs' ideas no longer corresponded. The collaboration therefore didn't last long. However, at the beginning, the external design was modernized in a new-objective style , and the subtitle also changed again, this time in a monthly magazine to create a new reality .

Young Conservative Phase (1929–1933)

In September 1929, Hans Zehrer took over the management of the paper and, together with Ernst Wilhelm Eschmann , Ferdinand Fried and Giselher Wirsing, made it an influential organ of the young, conservative “Tat-Kreis”. With a circulation of almost 30,000 copies, it reached around twice as many readers as the radical democratic weekly Die Weltbühne . Other authors of the TAT at this time were the pedagogue Horst Grüneberg , the politicizing dentist Hellmuth Elberecht and the military journalist Friedrich Wilhelm von Oertzen . Many other author names of the Tat articles, however, are pseudonyms that the above-mentioned members of the Tatkreis used to simulate a large editorial staff to the outside world.

The goals of the Tat-Kreis at this time are a peculiar conglomerate of “ left ” and “ right ” positions: Criticism of capitalism is combined with the call for national autarky and the demand for a new elite . The great popularity of this magazine prompted the publisher Gottfried Bermann Fischer, as a countermeasure, to discontinue his publishing house Peter Suhrkamp . He was supposed to bring the magazine Neue Rundschau , published by S. Fischer Verlag , on a more ideological course and thus stand up to the deed .

The act received the greatest attention in public: Siegfried Kracauer observed in 1931, “The magazine Die Tat has a strong following, especially among the intellectuals of the middle classes. It can be explained not only by the fact that the Tat-Kreis consciously advocates the practical and ideological interests of these strata, but also by the way it fights itself. It is of a format which the German intelligence was weaned. " The Berliner Tageblatt presented the same year already," a disconcerting neighborhood "of Tatkreises to national and anti-capitalist ideas of the group determined Strasser. Ebbo Demant later summed up in his investigation of the Tatkreis that the Tageblatt in particular soon went over to “condemning the empty phrases of the TAT group to the ground” and classifying it “as the literary guard of National Socialism” and to classify its members as "noble Nazis or salon Nazis". The writer Carl von Ossietzky again presented the following analysis of the Tat group in November 1932 in the Weltbühne : “Alongside Otto Strasser and Ernst Jünger, the Tat group most clearly represents the confusion of liberal citizens who are loud about the impending end of the world economy screaming and throwing right-wing extremism into the arms with ecstatic gestures. "

Foreign correspondents such as Sefton Delmer , Dorothy Thompson, Edgar A Mowrer and Alexander Lipianski also made Die Tat and the Tat-Kreis known outside of Germany and rated it as the "representative organ of young Germany" and "the country's leading political magazine."

After the transfer of power (1933–1939)

Zehrer was deposed as editor in October 1933. The adjustment course of Giselher Wirsing, who has meanwhile joined the SS , made the paper sink into insignificance. In 1939 it was given the new title “The XX. Century". It was merged with the magazine "Ostmark", the publisher remained the same. Co-editor was now Ernst Wilhelm Eschmann . The paper was discontinued in 1944. Authors of this time were in addition to the two editors z. B. Wolfgang Höpker , the anthroposophist Otto Julius Hartmann, Heinrich Anacker , Otto Kümmel , Hans Bethge , Erica Dieckerhoff, Fritz Meurer , Hans Heidrich, Joseph Martin Bauer , Georg Bräutigam, Bruno Brehm , Edwin Erich Dwinger , Detta Friedrich and Erwin Guido Kolbenheyer .

Tat pamphlets (selection)

- Friedrich Gogarten : Religion and Volkstum . Jena: Diederichs 1915. Tat pamphlets 5.

- Hermann Herrigel : Public Education and Public Library. A settlement . Jena: Diederichs 1916. Tat pamphlets 14.

- Max Maurenbrecher : New state sentiments . Jena: Diederichs 1916. Tat pamphlets 17.

- Wilhelm Rein : On the redesign of our education system . Jena: Diederichs 1917. Tat pamphlets 19.

- Georg Schmidt-Rohr : Our mother tongue as a weapon and tool of the German idea . Jena: Diederichs 1917. Tat pamphlets 20.

- Eduard Weitsch : What should a German adult education center be and achieve? One program . Jena: Diederichs 1918. Tat pamphlets 27.

- Paul Natorp : Student and Weltanschauung . Jena: Diederichs 1918. Tat pamphlets 29.

literature

- Hans Brunzel: Die "Tat" 1918–1933 , Diss. Phil., Bonn 1952

- Irmgard Heidler, the publisher Eugen Diederichs and his world. (1896 - 1930) (= Mainzer Studien zur Buchwissenschaft, Vol. 8), Wiesbaden 1998.

- Hans Henneke: " Ulrich Unfried " and the Tat-Kreis in: Criticón 182/183, 2004, pp. 43–46

- Edith Hanke & Gangolf Hübinger : From the “Tat” community to the “Tat” group . The development of a cultural magazine, in: Gangolf Hübinger (ed.): Meeting place of modern spirits . Eugen Diederichs Verlag - Departure into the Century of Extreme, Munich 1996, pp. 299–334

- Klaus Fritzsche: Political Romanticism and Counter-Revolution. Escape routes in the crisis of civil society: The example of the Tat-Kreis. Frankfurt a. M. 1976

- Kurt Sontheimer : Der Tatkreis, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 7, issue 3, 1959, pp. 229–260 PDF

- Siegfried Kracauer : riot of the middle classes . An examination of the “Tat” circle (1931), in: Ders .: Schriften , Vol. 5.2, Frankfurt / Main 1990, pp. 405–424

- Stefan Breuer: Anatomy of the Conservative Revolution Darmstadt 1993

- Alfred Weber : Selected Correspondence, (Alfred Weber Complete Edition), ed. by Eberhard Demm and Hartmut Soell, Marburg 2003.

- Eugen Diederichs : Life and Work. Selected letters and notes, ed. by Lulu von Strauss and Torney-Diederichs, Jena 1936.

- Marino Pulliero: Une modernité explosive. La revue The deed in les renouveaux religieux, culturels et politiques de l'Allemagne d'avant 1914–1918. Geneva 2008

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ernst Horneffer: Our goals, in: Die Tat , 1st vol., Issue 1 (April / 1909), p. 1

- ^ Fritzsche, Political Romanticism, p. 45.

- ↑ Sontheimer, Tatkreis, p. 231.

- ↑ See also Peter de Mendelssohn : S. Fischer und seine Verlag . S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt / Main 1986, p. 1246 f.

- ↑ References to the quotes in this paragraph (except Kracauer) from Ebbo Demant: From Schleicher to Springer. Hans Zehrer as a political publicist . v. Hase & Koehler Verlag, Mainz 1971, p. 77.

- ↑ Demant, Von Schleicher zu Springer , p. 77.

- ↑ February 28, 1895 in Graz - December 28, 1989

- ↑ obtained his doctorate from the University of Tübingen in 1944-1945 , no more known