Rock relief at Kızıldağ

Coordinates: 37 ° 30 ′ 21 ″ N , 33 ° 4 ′ 10 ″ E

The rock relief at Kızıldağ is a late Hittite relief in southern Turkey . These include three rock inscriptions in Luwian hieroglyphs and a cult site about 150 meters away with another inscription.

location

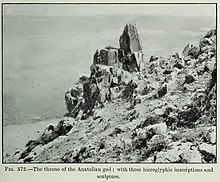

In the south of what is now Turkey, at the time of the Hittite empire, the Tarḫuntašša region , which was part of the empire at times, was located , whose rulers referred to themselves as great kings. In the area of Tarḫuntašša, after the collapse of the great empire in the 12th century BC, The neo-Hittite kingdom of Tabal , whose ruler was Hartapu , who also dubbed himself the Great King. The rock reliefs or inscriptions from Burunkaya , Karadağ and Kızıldağ are attributed to him. The massif of the extinct Karadağ volcano is located about 25 kilometers north of today's provincial capital, Karaman . The Karadağ inscription can be found on one of its peaks, the Mahalıç Tepesi . Another 15 kilometers north, in the Çumra district of Konya province , a rock cone rises up from the plain between the mostly dried up lakes Acıgöl and Hotamış Gölü near the village of Adakale , the 1140 meter high Kızıldağ. On its western flank, about halfway up, there is a single rock needle with a plateau, which has now been partially destroyed, on which the relief with the three inscriptions Kızıldağ 1, 2 and 3 is engraved. About 150 meters to the southeast there is an altar-like carved stone formation with the inscription Kızıldağ 4 . From both places there is a line of sight to the cult place with the inscription on the Karadağ.

Research history

The works were discovered on June 8, 1907 by William Ramsay on his trip to Turkey with Gertrude Bell and documented by both and published in 1909. Numerous researchers have followed them to this day. Publications appeared, among others, by Hans Gustav Güterbock in 1939, Sedat Alp in 1965 and Hatice Gonnet in 1981. John David Hawkins included the inscription in his Corpus of Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions in 2000 . Horst Ehringhaus finally described the monument in 2014 in his collection of late Hittite rock reliefs and inscriptions.

description

Rock needle

The plateau at the rock needle forms a structure with a rock standing vertically on it, which, following Ramsay, is commonly referred to as a throne . The upright backrest bears the relief and the inscription Kızıldağ 1 to the southwest . Depicted is a figure seated on a throne, looking up to the right towards the altar described later. The roughly head-high relief is executed as a line drawing, but not scratched, but rather chiseled into the stone. The throne is shown as a wooden construction with a high backrest, the side part has four filled compartments, including a presumably open compartment. The feet rest on a footstool. In contrast to Assyrian depictions, no throne images are known of Hittite rulers of the Great Empire, but there is great similarity to a depiction on the orthostat SVr 3 on Karatepe . Also from the 9th century BC Known hieroglyphic symbols for throne, seat ![]() (THRONUS) is comparable with the illustration. The king wears a high headgear that resembles a tiara . The face is bearded, under the cap the hair protrudes on the forehead and neck, which is tied back. Both hair and beard costumes show Assyrian influences. The same applies to the long robe, the lower edge of which is trimmed with fringes. The right hand resting on the armrest holds a flat drinking bowl, the left hand is stretched out and holds a ruler's staff.

(THRONUS) is comparable with the illustration. The king wears a high headgear that resembles a tiara . The face is bearded, under the cap the hair protrudes on the forehead and neck, which is tied back. Both hair and beard costumes show Assyrian influences. The same applies to the long robe, the lower edge of which is trimmed with fringes. The right hand resting on the armrest holds a flat drinking bowl, the left hand is stretched out and holds a ruler's staff.

In front of the head, the inscription is worked out as a high relief. It is 0.28 meters high and 0.33 meters wide and gives the name of the portrayed Hartapu (Ḫa-ta-pu-sa) with the sign on both sides for the great king ![]() (MAGNUS.REX), but without the winged sun above .

(MAGNUS.REX), but without the winged sun above .

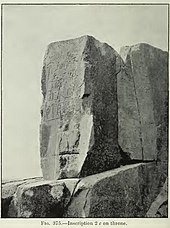

Large parts of the southern end of the platform have broken away, probably caused by treasure hunters being blown up. There were the inscriptions Kızıldağ 2 and 3 . Inscription 2 was applied flat on the surface, inscription 3 was applied vertically on the southern, 2.50 meter high face of the plateau. Like Kızıldağ 1, Kızıldağ 2 consists of the name and title of the great king, here arched by a winged sun. Above that there are a few characters, not all of which are clearly legible. The weather god Tarhunza is mentioned, probably a dedication to him. Today the inscription lies upside down in the sloping terrain. Kızıldağ 3 , the longest of the three scripts, is 0.80 meters wide and 1.40 meters high. It is the only one to have a narrative part and, in addition to the name, title and dedication, contains the Hartapus ancestry:

The Tarhunza.

Your Majesty, Hartapu, Great King.

(2) Mursilis, the great king, the hero

(3) son: He built the city here.

For a long time it was generally assumed in research that the father was Muršili III. is what Hartapu did in the early 12th century BC. Would date. Since the discovery of the stele of Türkmen-Karahöyük , another inscription by Hartapus, it is in the 8th century BC. The inscription is now lost, fragments of it may have been in the rubble of the slope. Both inscriptions, like the relief, are engraved with neat chisel strokes.

Step altar

About 150 meters southeast of the rock needle is the so-called step age on the slope of the summit plateau. From the southern end of the platform of the relief there is a line of sight to the altar and the inscription Kızıldağ 4 . The structure consists of three parts. In the middle there are several steps carved into the rock, on the left a 1.20 meter high stone block carved in the form of a seat and on the right the stone with the inscription. The explorer Ramsay considered the steps to be the beginning of an ascent to a fortress believed to be above it. Güterbock interpreted the structure in a similar way. Gonnet, on the other hand, interprets the complex as a cult altar, to which her Ehringhaus agrees. A cuneiform liturgy instruction from the Hittite period describes such places of worship, with the steps as well as the seat serving as a storage area for offerings in the form of bread and meat. There are also bowls on another boulder that were probably used for libation . This block lay on the inscription stone, fell down today, but parts of it are still preserved in the rubble. Similar altars are known from Phrygian times, but the steps in front of the gods reliefs in the Yazılıkaya sanctuary also had this function.

The two-line inscription Kızıldağ 4 is again executed in high relief, the lines are delimited by raised line separators. The upper line contains, unusually centered, the well-known name cartouche Hartapus with title and descent. In the bottom line, the creator gives a description of campaigns in which the king conquered various, unnamed countries as well as the land of Maša "forever". Since this was probably in the northwest of Anatolia, east of Wilusa , this statement gives information about the extent of Hartapu's empire.

On the summit plateau of the mountain, the remains of a surrounding circular wall built using polygonal technology can be seen. Remnants of the wall can also be seen further down, but they can also be older. Due to the lack of archaeological investigations, statements about their function are speculative, it is possible that they belong to the city mentioned in inscription 3. The occasional assumption that here or on the flat southern slope of the mountain was the location of the sought-after town of Tarḫuntašša, into which Muwattalli II. In the 13th century BC. Chr. Moved the capital of the Hittite Empire, is extremely unlikely due to the small size of the area.

There is a line of sight to the Mahalıç Tepesi in the Karadağ massif with the cult complex there from both the platform by the relief and the step altar .

stele

Piero Meriggi reports that a stele was found in the eastern area of Kızıldağ in 1963. Only a few signs were discernible on the stele, which was lying at the top and rounded at the top, the rest of the surface was weathered. Hawkins reads Mursi [lis], great king, hero there. Since then, no further sightings of the stele are known.

Dating

The timing of the relief and inscriptions is problematic. The clear Assyrian influence on the relief points to a late date of origin in the 8th century BC. Chr. Gonnet and others see in the forms of the step altar and the sacrificial benches evidence of an earlier date before the 10th century. According to Hawkins, on the other hand, the script shows purely archaic features and no parts of more recent scriptural tradition, according to which the texts should be dated to the end of the great empire in the early 12th century. It has also been suggested that the effigy of Wasusarma (8th century BC), the last king of Tabal, who wanted to pay homage to his early predecessor, was against what the Hartapu writings (probably 12th century BC) created themselves. Ehringhaus, on the other hand, points out that the sign of the Great King on the right of inscription 1 is significantly smaller than the one on the left, as otherwise it would collide with the ruler's staff. He sees this as strong evidence that the relief is older than the inscription. Since the discovery of the stele of Türkmen-Karahöyük , another inscription by Hartapu, Hartapu is now in the 8th century BC. Dated.

literature

- Eberhard P. Rossner: The Hittite rock reliefs in Turkey. An archaeological guide (= rock monuments in Turkey. Volume 1). 2nd, expanded edition. Rossner, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-924390-02-9 , pp. 90-98.

- John David Hawkins: Corpus of hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions . Volume 1: Inscriptions of the Iron Age . Part 1: Introduction, Karatepe, Karkamiš, Tell Ahmar, Maraş, Malatya, Commagene. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-11-010864-X , pp. 433–441, tables 236–239, 242.

- Horst Ehringhaus: The end that was a beginning. Rock reliefs and rock inscriptions of the Luwian states of Asia Minor from 12. to 8./7. Century BC BC Using epigraphic texts and historical information from Frank Starke . Nünnerich-Asmus, Mainz 2014, ISBN 978-3-943904-67-3 , pp. 14-28.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ WM Ramsay, Gertrude L. Bell: The Thousand and One Churches. Hodder and Stoughton, London 1909, pp. 505-512.

- ^ HG Güterbock: Eski ve yeni âbideleri / Old and new Hittite monuments. In: Halil Edhem hatıra kitabı / In Memoriam Halil Edhem. Türk Tarih Kurumu Yayınlarından, Ankara 1947, pp. 59–70.

- ↑ Sedat Alp: A new hieroglyphic Hittite inscription from the Kızıldağ-Karadağ group from the vicinity of Äksaray and the earlier published inscriptions from the same group. In: Anatolian Studies . Festschrift Güterbock. Istanbul 1974, p. 22 f.

- ^ Hatice Gonnet: Nouvelles données archéologiques relatives aux inscriptions hiéroglyphiques de Hartapusa à Kızıldağ. In: René Lebrun, Robert Donceel (Ed.): Studia Paolo Naster. Louvain-la-Neuve 1984, pp. 119-125.

- ↑ Reliefs | Reliefs SVr 4 and 3, inscription stone SVr 2 on Karatepe

- ↑ Petra Goedegebuure et al .: TÜRKMEN-KARAHÖYÜK 1: a new Hieroglyphic Luwian inscription from Great King Hartapu, son of Mursili, conqueror of Phrygia In: Anatolian Studies 70 (2020) pp. 29–43