Goderam

Goderam ( Latin Goderamnus , occasionally Goderamus , Goderannus or Goderammus , * before 975 ; † June 30, 1030 in Hildesheim ) was a Benedictine monk in Cologne and Hildesheim and since 1022 the first abbot of the St. Michaelis monastery in Hildesheim. He was the owner and connoisseur of the oldest surviving manuscript of the Ten Books on Architecture by Vitruvius , created in Carolingian times , and, as far as this can be said from the sources determined by " transmission chance and transmission chance", architectus caementarius , i.e. the executive architect, probably during the expansion of St. Pantaleon in Cologne at the end of the 10th century and possibly also during the construction of the Michaeliskirche in Hildesheim at the beginning of the 11th century.

Life

Goderam was the son of a margrave and became a clergyman. He was provost of the cathedral in Cologne before he became provost (deputy abbot) at the Benedictine monastery of St. Pantaleon in Cologne at the end of the 10th century , which had been founded under Otto I by his brother Brun . In autumn 1022, Goderam was appointed by Bishop Bernward as the first abbot of the Benedictine monastery of St. Michaelis in Hildesheim. He died on June 30, 1030.

Ten books on architecture by Vitruvius

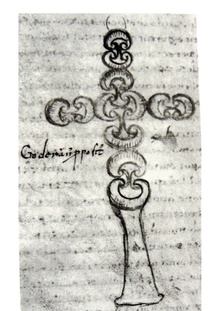

The work Ten Books on Architecture by Vitruvius from the 1st Century BC Was preserved in around 80 medieval manuscripts. In the oldest of these medieval copies, which was probably made after 800 at the court of Charlemagne , there are notably four marginal notes by Goderam and also the name and title of Provost Goderamnus next to the drawing of an extraordinary cross composed of sickle arches. It is on one of the three backs of the manuscript that had to be kept blank because the parchment was too thin to be written on on both sides. The manuscript is now in the possession of the British Library in London as Codex Harley Manuscript 2767 .

Goderam's entries in the manuscript have given rise to much speculation about him. The four marginalia scattered throughout the work show at least that Goderam was intensively involved with Vitruvius' work. It was very unusual for a monk who was not allowed to own property to label monastery property with his own name and also to comment on it with marginal notes. The surviving later owners of the manuscript make it plausible that Goderam did not take the work with him to Hildesheim, but rather left it in Cologne in St. Pantaleon.

Discussion of Goderam's Significance in Medieval Literature

Goderam evidently dealt intensively with Vitruvius' work on architecture. It is certainly not absurd to see in him a master builder and “architectus caementarius”, an architect in the modern sense who designs and draws construction plans and guides and supervises the construction workers and bricklayers.

It is quite conceivable that Goderam, who was provost under Abbot Everger at St. Pantaleon in Cologne, directed the extension of the hall and the new construction of the westwork of the monastery church, an extension of this early Romanesque church, which the Empress Theophanu commissioned which was not completed until 1002, over 10 years after the Empress' death.

Bernward, the tutor of Otto III. , the son of the widowed empress and regent, Goderam met in 991 at the funeral ceremonies for Theophanu, who died surprisingly and was buried in St. Pantaleon, before he was appointed Bishop of Hildesheim in 993. It is conceivable that Bernward was able to convince himself of Goderam's competence as a master builder on the construction site of the impressive St. Pantaleon Basilica.

Bernward's plans to found a Benedictine monastery on a hill not far from Hildesheim Cathedral must have taken concrete form soon after he took office in 993, so that his efforts to find a competent architect made him renew his contact with Goderam, in which he also had another talented one Metallurgists and goldsmiths and silversmiths appreciated.

In Medieval literature, however, the question of when exactly Goderam was in Hildesheim is quite controversial; between 996, 1016 and 1022 the data fluctuate, which are justified and rejected with different arguments.

For example, B. Christoph Schulz-Mons:

“To repeat it at this point: Goderam is not verifiable in Hildesheim before 1022, one looks in vain for his signature in the long list of witnesses under the foundation deed of November 1, 1019. […] That does not rule out that in the spring 1013 verifiable ranks of the convent of St. Michaelis also contain monks from St. Pantaleon. "

And Günther Binding is certain:

“[…] That St. Michael was only founded or founded in 1010 and the monks were only settled after 1011 and before 1013; thus Goderam can have come to Hildesheim at the earliest during this time, that is, after the laying of the foundation stone in 1010; he cannot have influenced the plan or the initial execution. "

However , only autumn 1022 remains as the documentary time for Goderam's appointment as abbot of St. Michaelis Monastery, probably one day in the week between November 3rd and 11th, 1022.

The chronicles of the Michaelis monastery in the form of short biographies of the abbots, kept by the monks of St. Michael since the founding days, provide a different picture. According to this, Goderam was appointed abbot by Bishop Bernward as early as 996.

This source comes in the form handed down here from the year 1521. Schulz-Mons proves in detail that these dates can certainly not be correct, as the construction of the Michaeliskirche here, which is not compatible with any other source, is set much too early. The clergy belonging to the cathedral seem to have been mistaken for brothers from the monastery.

Binding quotes another source, this time a list of the abbots and provosts from the St. Pantaleon monastery in Cologne. Although this does not contain an explicit date for the start or progress of construction, it sets Goderam's appointment as abbot in a chronological sequence to the construction of the church of St. Michaelis:

“Goderam, monk and provost of the St. Pantaleon Monastery in Cologne, became the first abbot of the excellent St. Michaelis Monastery in Hildesheim, after he was fetched from there by the Hildesheim Bishop Bernward, which was just founded and built by the latter , made."

From this, according to Binding, two things follow: that Goderam only came to Hildesheim as abbot and that when he was appointed the church was already built ( insignis Monasterii S. Michaelis intra Hildesium from eodem recens fundati et constructi ).

Regardless of these opposing facts, it is at least conceivable that Goderam was already in Hildesheim during the planning and construction of the Michaeliskirche, a thought that fascinates many historians. The division of labor between the client, Bishop Bernward, who, as architectus sapiens, designed the ecclesia spiritualis as a “heavenly Jerusalem”, and the site manager and actual architect, the architectus caementarius , who realized the ecclesia materialis, could be wonderfully exaggerated.

Hans Roggenkamp writes, for example

“This reading, applied to Bernward's position on St. Michael, leads to seeing in him the spiritual creator of the spatial concept. He may well be called Architectus sapiens, he who carried the idea of space within himself, was able to specify its dimensions and thereby drew from the knowledge and belief of a closed worldview. After the early medieval tripartite division of architecture into dispositio, constructio, venustas [design, construction, beauty], Bernward would most likely be assigned the task of the arrangement, Goderamus that of the construction. Bishop Bernward the scientist, Abbot Goderamus the magister fabricae, Vitruvius and Boethius both models and masters, these are the rational forces in St. Michael. "

In keeping with this division of labor, Nico Strube sees in the cooperation of Bernward and Goderam in the spirit of Vitruvius in the construction of the Michaeliskirche not only the influence of rational forces on St. Michael, but also the effect of a special spirituality .

literature

- Günther Binding : St. Michaelis in Hildesheim. Introduction, research status and dating. In: Lower Saxony State Office for the Preservation of Monuments, Christiane Segers-Glocke (Ed.): St. Michaelis in Hildesheim. Research results on the architectural archaeological investigation in 2006 (= workbooks on the preservation of monuments in Lower Saxony. 34.) CW Niemeyer, Hameln 2008, ISBN 978-3-8271-8034-6 , pp. 7–74.

- Hans Roggenkamp: Measure and Number. In: Hartwig Beseler , Hans Roggenkamp: The Michaeliskirche in Hildesheim. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1954, pp. 120–156, (Unchanged reprint. Evangelical-Lutheran Michaelisgemeinde, Hildesheim 1979).

- Christoph Schulz-Mons: The Michaeliskloster in Hildesheim. Investigations into the foundation by Bishop Bernward (993-1022) (= sources and documents on city history. Vol. 20, 1-2). 2 volumes (Vol. 1: Presentation. Vol. 2: Documentation. ). Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 2010, ISBN 978-3-8067-8738-2 .

- Nicolaus Strube: The special city guide. Blessed among the cities. Hildesheim and its spiritual legacy. Moritzberg Verlag, Hildesheim 2015.

Individual evidence

- ↑ So it says in the Chronica monasterii S. Michaelis from the year 1688: [Goderamus] Obiit autem pridie Kal. Julii anno 1030 et sepultus est ante altare sancti Stephani pede . German: "[Goderamus] died on the eve of July 1, 1030 and was buried in front of the altar of St. Stephen at the foot of the altar." Quoted from Schulz-Mons: The Michaeliskloster in Hildesheim. 2. Fig. 94, p. 79.

- ↑ Goderamnus primus Hildeneshemensium (!) Abbas 2nd cal. Julii obiit. Annales Hildesheimenses ad a. 1030 , quoted from Binding: St. Michaelis in Hildesheim - introduction, research status and dating. P. 30.

- ↑ According to Arnold Esch in his article of the same name in 1985, the interplay between these two factors determines the transmission of sources that can substantiate factual claims in a remarkable way. Arnold Esch: Tradition-Chance and Tradition-Coincidence as a Methodological Problem of the Historian, in: Historische Zeitschrift, 240 (1985), pp. 529-570 Online MGH Library; also in: Ders .: The historian and the experience of bygone times. Munich 1994, pp. 39-69.

- ↑ "Mason-Architect", a context of terms that goes back to Isidore of Seville (570–636) and was then once again taken over literally by Hrabanus Maurus (780–856): "architecti autem caementarii sunt, qui disponunt in fundamentis", ( “The bricklayers are those who lay the foundations” or “Architects are bricklayers who plan in the foundations”). In connection with medieval church building, the sentence of the Apostle Paul is always added to this, who applies the term architect metaphorically to himself when he uses it in 1 Cor. 3,10 says: “I laid the foundation like a wise architect.” Ut sapiens architector fundamentum posui . - Compare Günther Binding: Building Knowledge in the Early and High Middle Ages. In: Jürgen Renn et al. (Ed.): History of knowledge of architecture. Volume III. From the Middle Ages to the early modern period. Berlin 2014. an important architect of the Ottonian church building. P. 30.

- ↑ Binding and Schulz-Mons use the sources to discuss which dates are conceivable for Goderam's appointment as abbot and hold an appointment between the consecration of Michaeliskirche on September 29, 1022 and before the death of the founder Bernward on November 20 of the same year for possible. Since Bernward himself entered the monastery on November 11, 1022, shortly before his death, and exchanged his bishop's robe for a monk's robe, a " profession " that he probably made before the new abbot, November 11 is the latest Meeting. And since the certificate issued by Emperor Heinrich II for the imperial protection of the monastery only became legally binding on November 3rd, Goderam was probably installed in the week between November 3rd and 11th, 1022. See Schulz-Mons: The Michaeliskloster in Hildesheim. 1. S. 123 f. and binding: St. Michaelis in Hildesheim - introduction, research status and dating. P. 32.

- ↑ Details of an item from the British Library Catalog of Illuminated Manuscripts. Retrieved July 10, 2015 . see. also Schulz-Mons: The Michaeliskloster in Hildesheim. 1. p. 125 and p. 373. Volume 2. Fig. 65, p. 57 and Fig. 304, p. 179. See also: Binding: St. Michaelis in Hildesheim - introduction, research status and dating. P. 32.

- ↑ Several other owners are documented in the British Library. The next owner known by name, Johann Georg Graevius (1632–1703), was a lawyer and professor in the Rhineland, in Duisburg and Utrecht, which is closer to Cologne than Hildesheim.

- ^ Christoph Schulz-Mons: The Michaeliskloster in Hildesheim. Studies on the foundation by Bishop Bernward (993-1022) Volume 1, p. 373

- ^ Schulz-Mons: The Michaeliskloster in Hildesheim. 1., p. 373.

- ^ Binding: St. Michaelis in Hildesheim - introduction, research status and dating. P. 14.

- ↑ Chronica monasterii S. Michaelis : "Goderam was appointed as the first abbot of the monastery of St. Michael in Hildesheim by the holy and extremely pious Bishop Bernward in the year of the Lord 996." Goderammus primus abbas monasterii sancti Michaelis in Hildensem constituitur a sancto Barwardo praesule piissimo anno Domini 996 . Quoted from: Schulz-Mons: The Michaeliskloster in Hildesheim. Volume 2. P. 79. Schulz-Mons: The Michaeliskloster in Hildesheim. Volume 1, p. 165, however, does not consider this year to be reliable and points out that this version of the chronicles of the Michaeliskloster was not made until 1521.

- ^ Schulz-Mons: The Michaeliskloster in Hildesheim. 1. p. 165.

- ^ Binding: St. Michaelis in Hildesheim - introduction, research status and dating. P. 32.

- ^ Roggenkamp: Measure and number. P. 148.

- ^ Strube: The special city guide.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| --- |

Abbot of the St. Michaelis Monastery 1022–1030 |

Adalbert |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Goderam |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Goderamnus (full name); Goderamus (full name); Goderannus; Goderammus (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | first abbot of the St. Michaelis monastery in Hildesheim |

| DATE OF BIRTH | before 975 |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 30th 1030 or July 3rd 1030 |

| Place of death | Hildesheim |