Hawk falcon

| Hawk falcon | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

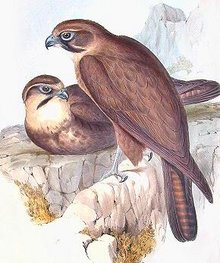

Hawk falcon ( Falco berigora ), reddish morph |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Falco berigora | ||||||||||||

| Vigors & Horsfield , 1827 |

The hawk falcon ( Falco berigora ) is a species of bird from the falcon-like family (Falconidae). It inhabits open or semi-open tree-covered landscapes in Australia and New Guinea, from semi-deserts to mountain forests. The hawk falcon is a little specialized predator, its diet consists of small mammals, birds and insects, which it catches in flight or on the ground. The population is estimated at several hundred thousand individuals, the species is considered harmless.

features

Appearance and build

The hawk falcon is a comparatively strong, medium-sized falcon with a clear sexual dimorphism in terms of size. The body length is 41–51 cm and the wingspan is 88–115 cm. Males usually do not reach the size of the smallest females. Females have a weight of 495–681 g and a wing length of 338–371 mm, the tail measures 193–217 mm. The weight of the males is between 340 and 419 g; the wing length is 315–334 mm, the tail measures 185–196 mm, which corresponds to about 75% of the body size of the female.

In the plumage drawing, however, there is no gender dimorphism, but there are different morphs . In addition, depending on age, region, gender or individual, further variations in the coloration can occur. Wax skin , beak and legs are whitish blue-gray in all morphs; slightly darker in juvenile animals. There are three morphs:

Brown morph

The brown morph is characterized by variable brown tones and patterns of the plumage, whereby the individual variation is considerable. The vertex, back of the head and neck are red to dark brown and covered with dark lines on the shaft. The nape of the neck shows a dark brown mark on both sides, which in some cases forms a collar. Throat, forehead and ear covers are white to cream in color; the width of the browband varies. Two dark, vertical stripes run along the ear covers. Together with the falcon-typical black beard stripes along the beak and throat and the likewise black brow stripe, it unites under the eye to form a dark band. The thin white stripe above the eyes usually extends far behind the eye and is often demarcated below by a fine black line.

The top is dominated by dark brown tones. The black shaft marks and light edges of the feathers usually result in a slightly inconsistent and dirty appearance. The coverts and the wing of the thumb are a little darker than the coverts and the back. The wing feathers are lightly banded on a dark background, whereby the dense and narrow banding results in a fine, regular dot pattern when the wings are spread. The control springs show the same drawing.

The underside varies greatly depending on the individual: the breast and abdomen can be predominantly cream-colored, covered with irregular brown-beige speckles and spots, or completely dark brown; the transitions are fluid. The pants are always brown; the flanks and axillary feathers are usually speckled with dark brown. The under tail-coverts, however, are banded beige in almost all plumage of the brown morph or brown on a beige background. The under wing coverts are variably speckled on a beige to dark brown background in different shades of brown; uniformly dark brown in dark birds. The underside of the flight feathers is white to light beige. The tips of the hand wings form a dark rim along the outer wing.

Reddish morph

Birds of the reddish morph are mainly characterized by the reddish-brown hue of their plumage, the pattern of which is otherwise similar to that of the brown morph. In place of the white, beige and sand-colored parts of the plumage of the brown morph, the reddish morph has slightly darker, rust-colored tones. The dark areas of the plumage, on the other hand, appear lighter and are more chestnut and reddish brown. This coloring is caused by the feather hems, which turn rusty in the reddish morphine. However, the birds show very different variants and flowing transitions to the brown morph. Especially on the ventral side, the spectrum ranges from light beige without any particular pattern to predominantly reddish brown with dark dots, but only very rarely pits. The facial drawing is less pronounced in light animals, thinner and lighter than in the brown morph; in some cases, lines behind the eyes and brow lines are barely noticeable. Only the beard stripes are clearly visible, but are also thinner. With dark plumage the facial markings are more pronounced and overall darker and stronger.

Dark morph

The dark morph appears almost entirely dark brown when seated and resembles dark representatives of the brown morph. Only below the beak is a yellow-brown spot that can reach down to the throat. The lower and upper side of the plumage are more or less uniformly black-brown to soot-brown. Reddish pits or feather edges shine through less than in the brown Morphe, and the only light parts - the finely dark banded undersides of the wings and tail feathers as well as the light bases of the large arm covers - are lighter. This results in a stronger black and white contrast in the plumage. The facial drawing is less evident than with other morphs due to the dark base color.

Juvenile birds

Juvenile plumage already resembles those of adult birds. However, they tend to be more uniform and darker brown in color. The light parts of the head and breast plumage are more reddish than cream or sand-colored. In juvenile birds of the brown morph there is a reddish collar around the neck that is missing in the reddish morph. Juvenile dark birds look very similar to adult ones, but a reddish tint due to feather hems is still clearly visible on the upper side.

Flight image

Hawk falcons appear in the field as small to medium-sized birds of prey with a falcon-typical appearance. The wings are slightly angled when gliding and the wrists are bent. The head protrudes clearly between the wings, the tail is elongated, rectangular and relatively wide when gliding.

Vocalizations

Hawk falcons are acoustically very active birds. Their calls are loud, croaking and resemble the screaming of parrots. Especially at dusk you can hear cackling, hoarse sounds, croaking or chicken-like chuckles. These calls vary with quick, rattling chatter or parrot-like screeches. In direct communication between two individuals, especially between partners, hawks tend to use quieter chuckles or croaks. Males approaching with food announce themselves with a sharp, scratchy kiieer ... kiieer . When a hawk hawk chases prey out of their cover, it cackles.

distribution and habitat

The hawk falcon is common throughout Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea all year round; however, the main distribution centers are in the southeast, in the center and in the southwest of Australia, in New Guinea without the Vogelkop Peninsula and in some scattered, smaller areas in the outback . Many offshore islands in Australia in the south and north of the continent are colonized by the falcon, as well as a number of islands on the north coast of New Guinea.

Hawk falcons are usually resident birds . Occasionally, however, individuals cover longer distances and juvenile birds leave the established territories of their parents. In the Australian winter, the number of train movements increases, but there is no clear pattern. In autumn, a particularly large number of juvenile hawks cross the Bass Strait . Overall, however, migratory movements seem to be due more to evacuation of the weather and changing food supplies than to primarily seasonal circumstances. The longest measured distance an individual traveled was 2047 km from South Australia to the northwest. Other long-distance hikes included 410 km northwest within South Australia and 406 km from Victoria over the Bass Strait to Tasmania.

The hawk falcon is not very picky about its habitat requirements. It is only missing in the rainforest and in dense eucalyptus vegetation. The diversity of the habitats it inhabits includes beach dunes through the Australian desert areas, farm and other cultural landscapes, forest edges and cleared areas to wooded mountain valleys in New Guinea. The habitats range from sea level to about 2000 m in Australia; in New Guinea the hawk falcon can also be found at altitudes of 2800 and occasionally even 3000 m.

Settlement density

The settlement density varies between 2.5 and 5.0 pairs per 100 km²; the highest settlement density was found in an area of 20 km × 3 km in size, where extrapolated a settlement density of over 10 pairs per 100 km² was achieved. The hawk falcon is less common in the arid outback and the New Guinea lowlands than in the rest of the range.

Hunting and feeding

The food spectrum of the hawk falcon is very broad. It includes mammals, birds, and ground-dwelling reptiles and insects. The proportion of the individual prey groups varies over the year: in Tasmania, birds dominated with 50% and mammals 40% of the total prey mass during the breeding season; outside the breeding season, insects and reptiles each consisted of around 40% each. In winter, the population studied ate mammals (30%), carrion (30%) and birds (20%). The mammals captured are mainly hares, wild rabbits and mice . The weight of beaten rabbits is up to 1 kg, sometimes rabbits weighing 2 kg are beaten. Smaller species dominate among the birds, especially starlings ( Sturnus vulgaris ). Occasionally, hawk falcons also prey on birds weighing 300 g and also attack significantly larger species. Jumpers and beetles predominate among the insects .

Larger prey are usually spotted and hunted from a seat guard, but sometimes also from gliding. Hawk hawks also often fly fast and low above the ground to chase potential prey from their cover. Sometimes two birds work together, one shooing the prey out of its hiding place and the other then striking it from a great height. Reptiles and invertebrates are mostly followed from the ground on foot and grasped with the claws. Hawk falcons often also follow combine harvesters, tractors or herds of cattle in order to capture fleeing insects. The fronts of field fires are also an attraction for hawks. Occasionally they transport burning branches in order to be able to catch prey by spreading the fires. Sometimes they also practice kleptoparasitism by chasing prey from other predators.

Social behavior

Adult hawk falcons usually live alone or in pairs. From time to time, however, larger groups also come together; this behavior is even more common in immature birds. Such loose associations take place especially when abundant sources of food are available and can lead to the formation of swarms with more than 100 individuals.

Reproduction and breeding

The breeding season is variable depending on the geographical latitude and probably also depending on the food supply. In Tasmania and southern Australia, it usually begins in September and lasts until January, but it can also start as early as June and end in February. In northern Australia and New Guinea, breeding usually takes place between April and November, less often December. It is unclear how closely the birds are tied to these periods; However, it has not yet been possible to determine that hawks breed every month of the year.

Courtship

At the beginning of the breeding season, hawk falcons perform various flight maneuvers, which are accompanied by loud calls. For example, they circle at great heights, perform dips, rolls, zigzag flights or stylized hunting maneuvers at low altitudes. This is acoustically accompanied by loud cackling and croaking.

Brood

Hawk falcons, like all falcons, do not build their own nests, but use abandoned breeding grounds of other birds or natural hollows, caves or hollows for their nest. These are only supplemented by some additional material such as twigs or pieces of bark. The height of the breeding sites used can be any height up to 50 m above the ground. The female usually lays two to three eggs, less often one to five eggs are found in a clutch. The nestlings hatch 31-36 days after egg-laying and fledge after a further 36-41 days. The dependence on the parents then dragged on for about six weeks.

Taxonomy

Research history

The first description was in 1827 by Thomas Horsfield and Nicholas Aylward Vigors in their Wer A description of the Australian birds in the collection of the Linnean Society; with an attempt at arranging them according to their natural affinities . The specific epithet berigora , which they gave the taxon, is derived from an Aboriginal name of the bird.

Systematics

At least eight subspecies have been described for the hawk falcon. The Handbook of the Birds of the World recognizes three of them, James Ferguson-Lees and David Christie reduce these by one more in their handbook Raptors of the World .

- F. berigora berigora Vigors & Horsfield, 1827 : nominate form , common in the humid part of Australia.

- F. berigora novaeguineae ( AB Meyer , 1894) : Widespread in New Guinea and the offshore northern islands.

- F. berigora occidentalis ( Gould , 1844) : Arid regions of the Australian interior.

For Ferguson-Lees and Christie, F. berigora occidentalis is ruled out as a subspecies because all populations of the hawk falcon show strong color variations and therefore all birds of Australia and Tasmania should be considered as belonging to a subspecies. Certain patterns emerged, such as an accumulation of reddish morphs in arid areas or the appearance of particularly bright animals in Tasmania; however, these did not justify a division into subspecies. Ferguson-Lees and Christie only approve the status of a subspecies for the New Guinea hawk falcons, as they are consistently darker and more distinct in their plumage than Australian birds.

Existence and endangerment

The hawk falcon is one of the most common falcon-like in Australia; Ferguson-Lees and Christie estimate the population at several hundred thousand birds, Tom Cade estimated 225,000 breeding pairs in 1982. There are currently no serious threats to the populations anywhere in the range. Hawk falcons are occasionally shot or trapped, but declines can only be observed locally and are probably due to carcass poisoning in winter or to pesticides.

swell

literature

- James Ferguson-Lees , David A. Christie: Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001, ISBN 0618127623 , pp. 284 & pp. 832-834.

- Stephen Marchant, Peter Higgins (Eds.): Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Vol. 2: Raptors to Lapwings. Oxford University Press: Melbourne, 1993. ISBN 0-19-553069-1 , pp. 237-253.

- Paul G. McDonald, Penny D. Olsen , Andrew Cockburn: Sex allocation and nestling survival in a dimorphic raptor: does size matter? In: Behavioral Ecology 16, 2005. pp. 922-930.

- Paul G. McDonald, David Baker-Gabb: The Breeding Diet of Different Brown Falcon ( Falco berigora ) Pairs Occupying the Same Territory over Twenty Years Apart. In: Journal of Raptor Research 40 (3), September 2006. pp. 228-231 .

Web links

- Brown Falcon, Falco berigora . Global Raptors Information Network, 2010.

- Hawk hawk literature on the Global Raptor Information Network

- Falco berigora inthe IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013.1. Listed by: BirdLife International, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Stephen Marchant, Peter Higgins (Ed.): Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Vol. 2: Raptors to Lapwings. Oxford University Press: Melbourne, 1993. ISBN 0-19-553069-1 , pp. 237-253.

- ↑ a b James Ferguson-Lees, David A. Christie: Raptors of the World . Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2001, ISBN 0618127623 , p. 284

- ↑ Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001, p. 833.

- ↑ a b c Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001, p. 832.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001, p. 834.

- ↑ a b Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001, pp. 833-834.

- ↑ Intentional Fire-Spreading by "Firehawk" Raptors in Northern Australia [1]

- Jump up ↑ Burn, Baby, Burn: Australian Birds Steal Fire to Smoke Out Prey [2]