Harishchandra

Harishchandra ( Sanskrit हरिश्चन्द्र hariścandra "shiny gold") is in Indian mythology a king of Ayodhya from the Suryavamsha dynasty, son of Trishanku . His myth shows him as an exemplary pious person who never lied and never broke his word, whatever it should cost him.

Legend

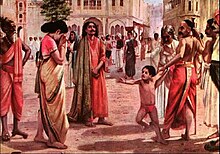

The most detailed legend about the life of the pious king is told in the Markandeya Purana . Accordingly, one day the king was riding through the forest when he heard the pitiful cries of women in need. The king, always ready to assist virgins in need in every way, rode up to the spot and saw there the great rishi and sage Vishvamitra , the master of all sciences, who was in the process of mastering the sciences which had taken the form of beautiful women . They complained loudly about the violent grip of the strict scholar and the king had heard these screams. The wise Vishvanitra, however, was extremely angry with the king's interference with his studies. He offered the angry Rishi as penance for failing to give him whatever he wanted, be it gold, his kingdom, wife, son or his own body. Vishvamitra found the kingdom of Harishchandras and all of its possessions as appropriate as a balance and as a gift ( dakshina ) due to him as a brahmin . He was allowed to keep his wife and son for the time being and a dress made of tree bark as a robe. In such extreme poverty he emigrated with his wife Shaibya ( शैब्या śaibyā ) and his son Rohitashva ( रोहिताश्व rohitāśva ) to the city of Varanasi , since this city, holy to Lord Shiva, was the only one not under the influence of the cruel Vishvamitra.

In Varanasi, however, Vishvamitra was already waiting for them and asked Harishchandra to give him more gifts, whereupon the latter first had to sell his wife and son and finally himself into slavery. His master became a Chandala , a disgusting slave owner who beat him to steal the shrouds of the dead at night on the Smashana , the place of the cremation. After twelve months of doing this most contemptuous of all conceivable activities, his wife came to the Smashana, as she performed the rites there for her son, who, as Harishchandra now learned, had since died from a snake bite. Harishchandra and Shaibya agreed that in their utter misery, they would cremate themselves at the stake with their son's body. Harishchandra hesitated, however, since he was not master of his life as a slave, to kill himself without the consent of the Chandala.

Then the gods Indra and Vishnu appeared and revealed to him that he had earned a place in heaven through his extreme piety and superhuman devotion in the greatest suffering. But Harishchandra thought that he could not accept this offer without the consent of his master, the Chandalas. Then Dharma , the god of justice, who had assumed the form of the slave owner, revealed himself and allowed him and his family to ascend to heaven. Vishvamitra renounced all his claims and handed the kingdom over to the revived Rohitashva. But now the noble king objected that he could not go to heaven without his loyal subjects, whereupon Indra created a city in heaven, in which Harishchandra with his family, his friends and all his followers should lead a blissful life.

In the Aitareya Brahmana it is said that the childless king swore to the god Varuna that if he had a son he would sacrifice him to the god. A son was born to the king whom he named Rohita. However, when he was about to fulfill his oath, Harishchandra repeatedly delayed the sacrifice with various excuses. First a suitable victim had to be at least 10 days old, then it had to have teeth, then it had to be permanent teeth and finally the boy had to be of the age of weapons. When Rohita was finally at this age too, the father could no longer find a new escape and prepared to sacrifice the son, Rohita refused and fled into the forest, where he lived for six years and met a starving Rishi named Ajigarta , who sold him one of his three sons as a substitute sacrifice.

Rohita then went with Shunashepa , as the son was sold, to his father, who found the substitute sacrifice acceptable and the god was also satisfied with it, since the son of the Rishi was a brahmin , but Harishchandra's son only belonged to the warrior caste of the Kshatriya . At the offering ceremony, however, no one was willing to tie up the victim until Shunashepa's greedy father offered to bind his own son. When the slaughter was to be carried out at the climax of the sacrificial rite, again no one wanted to carry out the deed until Ajigarta agreed to kill her own son for a third hundred cattle. But he prayed to the gods, who finally saved him from sacrificial death. Vishvamitra , who had acted as one of the sacrificial priests in the planned sacrifice, namely as Hotri (reciter), finally accepted Shunashepa, who now no longer wanted to have anything to do with a return to his father, in place of his son.

reception

Mahatma Gandhi

Harishchandra can be seen as the embodiment of the Satya concept of Indian philosophy through his truthfulness and sincerity practiced to the last consistency . In any case, this is how the legend affected Mahatma Gandhi , who, as a boy, saw a theatrical adaptation of the material, which deeply impressed him and led him to ask why not everyone like Harishchandra leads a life of complete truthfulness. This life in truth, for the truth and the insistence on or clinging to the truth became a central part of his philosophy and found its expression in the development of the concept of Satyagraha .

Film adaptations

On a popular level, the Harishchandra material has been picked up on many occasions in Indian cinema. The earliest adaptation, Raja Harishchandra , was made in 1913 under the direction of Dhundiraj Govind Phalke and was the first full-length feature film in Indian cinema. Harishchandrachi Factory , a Marathi biopic about Phalke (2009, director: Paresh Mokashi) is about the making of this film . Another adaptation, Ayodhyecha Raja from 1932, directed by Indian film pioneer V. Shantaram with Govindrao Tembe and Durga Khote in the lead roles, was the first Marathi sound film. In the same year a Hindi version appeared under the title Ayodhya Ka Raja . Further film versions are:

- Satyavadi Raja Harishchandra (silent film, 1917, Dhundiraj Govind Phalke, remake of the 1913 film)

- Satyawadi Raja Harishchandra (silent film, 1917, Rustomji Dhotiwala)

- Raja Harishchandra (silent film, 1924, DD Dabke)

- Raja Harishchandra (silent film, 1928, YD Sarpotdar)

- Harishchandra (silent film, 1931, Kanjibhai Rathod)

- Satyawadi Raja Harishchandra (Hindi, 1931, JJ Madan)

- Harishchandra ( Tamil , 1932, Sarvottam Badami and Raja Chandrasekhar)

- Harishchandra ( Telugu , 1935, P. Pullaiah and Rajopadhyay)

- Satya Harishchandra ( Kannada , 1943, R. Nagendra Rao)

- Harishchandra (Telugu, 1943, Kadaru Nagabhushanam)

- Harishchandra (Tamil, 1944, AT Krishnaswamy and AV Meiyappan)

- Satyawadi Harishchandra ( Gujarati , 1948, Dhirubhai Desai)

- Raja Harishchandra (Hindi, 1952, Raman B. Desai)

- Harishchandra ( Malayalam , 1955, Anthony Mithradas)

- Harishchandra ( Bengali , 1957, Phani Burma)

- Harishchandra (Hindi, 1958, Dhirubhai Desai)

- Harishchandra (Telugu, 1960, Chandrasekhara Rao Jampana)

- Harishchandra Taramati (Hindi, 1963, BK Adarsh)

- Satya Harishchandra (Kannada, 1965, Hunsur Krishnamurthy)

- Satya Harishchandra (Telugu, 1965, Kadri Venkata Reddy)

- Harishchandra (Tamil, 1968, KS Prakash Rao)

- Harishchandra Taramati (Hindi, 1970)

- Harishchandra Taramati (Gujarati, 1974, Babubhai Mistri)

- Raja Harishchandra (Hindi, 1979, Ashish Kumar)

- Raja Harishchandra ( Oriya , 1984, Rao CSR)

- Satya Harishchandra (Telugu, 1984, Rao CSR)

- Harishchandra Shaibya (Bengali, 1985, Ardhendu Chatterjee)

As you can see, until the mid-1980s there was hardly a year in which the material was not made into a film (sometimes several times).

literature

- Arthur Berriedale Keith: Rigveda Brahmanas: the Aitareya and Kausītaki Brāhmanas of the Rigveda . Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1920, pp. 299-309.

- Harishchandra . In: John Dowson : A classical dictionary of Hindu mythology and religion, geography, history, and literature. Trübner & co., London 1879, pp. 118-119 ( Text Archive - Internet Archive ).

- Jan Knappert: Lexicon of Indian Mythology. Heyne, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-453-07817-9 , pp. 146-148.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hariścandra . In: Monier Monier-Williams : Sanskrit-English Dictionary . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1899, p. 1290, col. 3 - 1291, col. 1 .

- ↑ Aitareya Brahmana VII, 3

- ↑ Ratana Dasa: The global vision of Mahatma Gandhi. Sarup & Sons, New Delhi 2005, p. 5

- ↑ Raja Harishchandra (1913)

- ↑ IMDb query