Ijen

| Ijen | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Ijen crater lake |

||

| height | 2769 m (1999) | |

| location | Java Island , Indonesia | |

| Coordinates | 8 ° 3 '29 " S , 114 ° 14' 31" E | |

|

|

||

| Type | Stratovolcano | |

| Last eruption | 1999 | |

| First ascent | 1789 | |

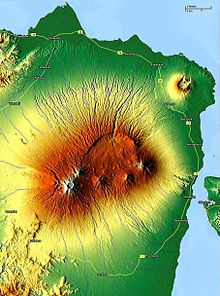

Ijen (earlier spelling "Idjen") is the name of a volcanic complex in Jawa Timur , the easternmost province of the Indonesian island of Java . Best known in this huge complex, whose base diameter is 75 km, is the crater lake Kawah Ijen , enclosed by bare walls , which some geologists and mineralogists refer to as "the largest acid barrel on earth". With its acidic turquoise water and its violently steaming solfatars , it is an impressive tourist destination, but for safety reasons it is not always freely accessible.

The 3332 m high layer volcano Gunung Raung rises in the immediate south-west .

Linguistic notes

- The maps and profile views were partly created during the Dutch-Indian colonial era. The Dutch “oe” corresponds to today's “u” ( Koekoesan = Kukusan , Goenoeng = Gunung , Raoeng = Raung ), “dj” corresponds to today's “j”. The village of Jambu on the southern slope of the Merapi, near which there is an observatory, is marked on the map of the Ijen Mountains with the name "Djamboe". In the post-colonial period, “j” was changed to “y” (example: Banjoepoetih = Banyuputih ).

- Indonesian Gunung 'mountain'

geography

The Ijen highlands

After its collapse, an elliptical caldera remained of an original twin volcano , probably formed in the Young Pleistocene , whose height has been estimated by the Dutch volcanologist Georg Laure Luis Kemmerling to be 4000 m , which is one of the larger calderas with a diameter of up to 16 kilometers Earth is. About 80 cubic kilometers of volcanic ash and pumice were thrown out in this collapse; they form a 100 to 150 m thick layer, which is mainly deposited on the northern outer slopes of the caldera.

Subsequent volcanic activity meant that this caldera is only partially present. The northern semicircular rim of the caldera , the up to 1717 m high Kendeng Mountains , through the middle of which the Banyuputih River has carved a difficult-to-access gorge, some 500 m deep, and the northern half of the caldera floor, which is about Ijen highlands rising from 900 m to 1500 m to the south. The deepest point of this highland is 850 m above sea level near the village of Blawan .

The rivers have dug deep into this volcanic plateau, which is covered with tuffs and loose ejections. Most important is the acidic banyupahit ('bitter water'), which drains the crater lake Kawah Ijen. Both the Banyupahit and its tributaries, the Kali Sat coming from the left at Blawan and the Kali Sengon coming a little further below from the right, have washed out canyon-like valleys up to 200 meters deep with partially vertical walls. Dissolved minerals from hot springs at Kali Sengon and Banyupahit give the acidic water a milky-light color through chemical reactions, which is why the Banyupahit has received the name Banyuputih ('White River') from here.

Broken lava layers are overcome by waterfalls. Such a waterfall of the Banyuputih, immediately before its breakthrough through the Kendeng Mountains, opened up the bottom of the originally horizontal caldera at about 780 m above sea level. The current rise of the caldera floor to the south was heaped up by several secondary volcanoes, whose ramparts and cones shape the landscape of the southern Ijen highlands.

The southern half of the original caldera was buried under a row of volcanoes that arose on an east-west fault line . The most important in this series is the Ijen-Merapi, a twin volcano on the eastern edge of the caldera. The older 2799 m high stratovolcano Gunung Merapi (not to be confused with the highly active Merapi in Central Java) has died out. On its western flank is the active 2386 m high Gunung Ijen with the crater lake Kawah Ijen.

The Ijen volcano

The main attraction of the Ijen complex is the Gunung Ijen crater with the world famous lake Kawah Ijen. This crater shows great morphological differences between the western and eastern parts. To the west, the ribs on the outer slopes of the volcano extend to the rim of the crater, which has accelerated the erosion of the western rim. In the north, east and south the ribs end below the rim of the crater, which has a much higher stability and is a well-preserved ring wall of almost the same height all around. In addition, the western part consisted of products that offered little resistance to the eroding forces. The eastern part, which consists of more solid material, is supported by two older crater walls and by the neighboring Merapi.

In addition, the eruption point has been relocated several times: the oldest building unit was designated K3 on the maps of the twin volcanoes Ijen-Merapi and Kawah Ijen . This crater can only be recognized as a narrow plateau on the southern slope of the volcano. After that, K3 was overlaid by K2 crater in the eastern part of today's crater. The youngest building unit is the crater K1, and here in particular the slopes in the western part on both sides of the overflow of the lake.

As a result, the western rim of the crater was largely destroyed and the overflow of the crater lake is located here. The destruction of this edge was not only caused by erosion, but also by a lava flow, which can not only be seen in a large dome-shaped plug to the left behind the overflow, but has also been detected in many places further down, and by phreatic eruptions that ejected part of the crater lake. The resulting mud flows ( lahars ) deepened the breach in the western edge and reduced the level of the lake's surface to the current height of 2148 m above sea level. The traces of the lahar from 1817 can still be clearly seen, which flooded the Ijen plateau along the Banyupahit, the upper reaches of the Banyuputih, through the Banyuputih gorge on the northern edge of the caldera into the coastal plain and east of the city of Asembagus like a fan Delta flowed into the sea.

Lake Kawah Ijen, embedded in the Ijen crater, is 960 m long, 600 m wide and up to 200 m deep. Its surface is 41 hectares. There are clear correlations between the different amounts of precipitation, the height of the lake level and the water temperature. Between the dry season from May to October and the wet season from November to April, the height of the lake level differs by up to four meters. As a result, the volume of the lake varies from 32 million to about 36 million cubic meters. The intense blue-green color of Kawah Ijen is caused by its high content of alum , sulfur and gypsum . The alum content is estimated at over 100,000 tons.

The water of this lake is extremely acidic: Analyzes in 2005 and 2006 found a pH value below 0.3 in the lake and between 0.4 and 0.5 in the Banyupahit runoff. Inflows with neutral water increase the pH value up to the breakthrough of Banyuputih in the northern edge of the caldera to 3.0 to 3.5, depending on the water flow.

The temperature of the lake water is subject to strong fluctuations. In the long term, an upward trend was observed. In October 2000 32 ° C was measured, in the following years 35 ° C to 45 ° C. The highest value so far is 48.1 ° C, measured on July 13, 2004 (as of November 2007). Clouds of vapor almost always develop on the lake because the water temperature is higher than the air temperature.

On the south-eastern shore of the lake is one of the most active solfataras on earth, which has deposited the most significant sulfur accumulation in Indonesia with fumaroles with a temperature of 190 to 240 ° C with sulfur banks up to 8 meters thick. In 1968 the official opening of a sulfur mine took place. Sulfur vapors are conducted through a sophisticated system of around 10 m long and 50 cm thick pipelines to deeper extraction points, where the sulfur emerges as a viscous orange to red-colored mass at 110 to 120 ° C and only turns into a bright yellow after cooling. Local workers use iron bars to break off the sulfur. Porters use two bamboo baskets to transport the broken pieces to the crater rim, which is 200 m higher, within two hours, and from there to the valley with several handcarts donated by a wealthy Indonesian. Up to six tons of sulfur are carried to a collection point in this laborious way every day, an amount that the solfataras compensate for every day. Due to overheating, the sulfur occasionally ignites by itself and flows into the lake as a light blue burning stream, whose luminosity offers a mystical spectacle, especially in the dark of night.

In the past, after heavy rains, the acidic water of the Kawah Ijen flowed over the breach in the western rim of the crater, united on the Ijen plateau with the tributaries of the Banyupahit, flowed with the Banyuputih through the gorge in the northern edge of the caldera and caused great damage to the rice fields and the Sugar plantations existed on the northern coastal plain. In 1921, a sluice was built in the overflow of the Kawah Ijen, which prevents the acidic water from flowing away. The walls of this lock are made of sulfur blocks because other building materials cannot withstand the acidic water. Furthermore, all irrigation drains of the Banyuputih were provided with sluices. If the lake level rises above a critical level, the locks of Banyuputih are closed. In the event of a major phreatic outbreak, however, these protective measures are ineffective: the lahars that flowed down in November 1936 could not stop the lock on Kawah Ijen. The source of the outflow of the Kawah Ijen, the Banyupahit, is located downstream below this sluice; here the acidic water of the lake has paved an underground course through the ash mantle of the volcano.

History of the outbreaks, first visits from scientists

In 1792, a volcanic earthquake caused a landslide on the eastern slope of the Merapi, which swept with devastating force over the eastern coastal plain and reached the sea north of Banyuwangi .

The oldest record of a phreatic eruption of the Ijen dates from 1797, recorded in Thomas Horsfield's mineralogical map of Java. The name of the mountain was mistakenly given as "Tashem".

The first Europeans to reach the rim of the crater were in 1789 the commander of the fort "Utrecht" in Banyuwangi, Clemens de Harris , and a companion from whom instead of his name only the term "used" for a European who had long served in the Dutch East Indies. Oudgast ”has come down to us. From the stories of this Oudgastes it emerges that the two men on the southeast side of the crater descended with the help of rotang to the shore of the lake near the solfataras. In their report, which is contradicting in many respects, published in the Bataviasche Courant newsletter in October 1820 , only the last sentence is significant: "Since 1790, all the sulfur that is processed in the powder mills in Semarang and Batavia has been extracted from the Idjen."

On September 20, 1805, the French botanist Jean-Baptiste Leschenault de La Tour visited the Ijen. Except for the highest crater rim, the mountain was covered with lush forest, and even on the steep inner walls of the crater, bushes with ferns ran down to the ground. Only in the south-west corner of the bottom was a greenish-white lake with a steaming-hot surface. Three-quarters of the ground was covered with hot ash, and sulfur fumes were escaping from crevices and holes.

In 1806 the American naturalist Thomas Horsfield examined the Ijen. He essentially confirmed the observations made by his predecessor and was the first to examine the lake's runoff.

Eleven years later, from January 24 to February 18, 1817, lahars flowed not only over the Ijen highlands, but also eastwards towards Banyuwangi; the number of people who died is not known. The vegetation was destroyed up to 600 m below the summit. Four years later, the German botanist Kaspar Georg Karl Reinwardt found the mountain completely bare, while Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn found grass and shrubbery and even casuarines up to 16 m high on the outer slopes in 1844 .

From late February to mid-March 1917 the lake seemed to be boiling; Mud was thrown 8 to 10 m above the lake surface. Gas outbreaks took place in 1921 and 1923. In another violent phreatic eruption, from November 5th to 25th, 1936, lahars poured down into the valley with similar violence as in 1817. The vegetation was destroyed so permanently that the rim of the Ijen crater has remained bare to this day. As a result of this eruption, an observation station "Pondok Bunder" (round hut), which is still in ruins today, was built, which was manned by 3 men. In 1952 boiling mud and sulfur were thrown from the lake; the resulting cloud of steam was over 1,000 meters high. On April 13, 1962, gas bubbles with highly toxic carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide up to 10 m in diameter rose up in the lake. Five days later, the water surged 10 meters and changed color. In 1976 49 out of 50 sulfur workers suffocated in a gas eruption. In 1989 another 25 sulfur workers died. Earth tremors took place from March 16 to 28, 1991; again the water surged and changed color. Similar eruptions with poisonous gas eruptions occurred in 1993, 1994, 1997 and 1999.

The volcano is considered so unpredictable that danger zones 8 and 12 kilometers in diameter have been established. Possible tracks of glowing clouds and lahars run far beyond these danger zones to the northern and eastern coastal plains. On the southern slope of the Merapi, near the village of Jambu, the Ijen is monitored by an observatory, which has been recording increasing activity with earth tremors and gas eruptions since 1991.

See also

literature

- Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn : Java its shape, plant cover and internal construction. Leipzig, Arnoldische Buchhandlung, 2nd volume, 1854 (1st edition) and 1857 (unchanged 2nd edition), pp. 691–721. From p. 707 to 710 a detailed description of the 1817 eruption of the Ijen.

- Emil Stöhr: The province of Banjuwangi in East Java with the volcanic group Idjen-Raun. Travel sketches. Frankfurt a. M., Christian Winter, 1874. In: Treatises of the Senckenberg'schen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft, Volume IX.

- GLL Kemmerling, HW Woudstra: De geologie en geomorpologie van den Idjen en analyze van merkwaardige watersoorten op het Idjen hoogland. Uitgegeven van de Koninklijke Natuurkundige Vereeniging bij G. Kolff & Co., Batavia-Weltevreden, 1921. 162 pages with maps and illustrations.

- NJM tavern: Vulkaanstudiën op Java . Volcanological Mededeelingen No. 7. Publisher: Dienst van den Mijnbouw in Nederlandsch-Indië. 'S-Gravenhage, Algemeene Landsdrukkerij, 1926. pp. 99-102.

- M. Neumann van Padang: Catalog of the active volcanoes of Indonesia. ( Catalog of the active volcanoes of the World including solfatara fields. Part I ). International Volcanical Association, Napoli 1951. pp. 156-159.

- Crater lakes of Java: Dieng, Kelud and Ijen. Excursion guide book . IAVCEI General Assembly, Bali 2000. pp. 25-43.

- A. Lohr, A. Laverman, M. Braster, N. Straalen, W. Roling: "Microbial Communities in the World's Largest Acidic Volcanic Lake, Kawah Ijen in Indonesia, and in the Banyupahit River Originating from It" . In: “Microbial Ecology” , vol. 52, Nov. 2006, pp. 609-618.

- AJ Lohr, TA Bogaard, A. Heikens, MR Hendriks, S. Sumarti, MJ van Bergen, CA van Gestel, NM van Straalen, PZ Vroon, B. Widianarko: Natural pollution caused by the extremely acidic crater lake Kawah Ijen, East Java , Indonesia. In: Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. , Institute of Ecological Science, Vrije Universiteit, De Boelelaan 1085, NL-1081 HV Amsterdam, vol. 2005, Afl. 12 (2), pp. 89-95.

Web links

- Ijen Volcanic Complex (English; PDF file; 1.09 MB)

- Ijen in the Global Volcanism Program of the Smithsonian Institution (English)

- Sulfur mining at Kawah Ijen

- First part of a film about sulfur degradation

- Second part of a film about sulfur degradation

- At night on Kawah Ijen . The Boston Globe , December 8, 2010

Individual evidence

- ^ Transporting sulfur to the rim of the SPON crater , accessed on September 26, 2019