Invicta International Airlines Flight 435

| Invicta International Airlines Flight 435 | |

|---|---|

|

Invicta International's Vickers Vanguard crashed. |

|

| Accident summary | |

| Accident type | Controlled flight into terrain |

| place | 300 m south of Herrenmatt, Hochwald SO , Canton Solothurn |

| date | April 10, 1973 |

| Fatalities | 108 |

| Survivors | 37 |

| Injured | 36 |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Vickers vanguard 952 |

| operator | Invicta International Airlines |

| Mark | G-AXOP |

| Passengers | 139 |

| crew | 6th |

| Lists of aviation accidents | |

The Invicta International Airlines Flight 435 was a charter flight en route from Bristol to Basel , in the April 10, 1973 Hochwald ( Canton Solothurn crashed). It is the most momentous aircraft accident in Switzerland to date and at the same time the most momentous aircraft accident involving a Vickers Vanguard 952 . 108 people were killed in the crash, 37 survived because they were in the rear of the aircraft.

The aircraft, a four-engine turboprop aircraft with the aircraft registration G-AXOP, was on the way on behalf of a British charter airline and was supposed to fly to Basel-Mulhouse airport . There was fog and blowing snow. Despite the approach, the pilots missed the runway with the help of the instrument landing system, which started a random flight in the Basel region. The machine finally crashed on a slope near Hochwald.

Flight history

The plane was on its way from London-Luton Airport to Basel. It had landed at Bristol Airport and took off there at 7:19 a.m. GMT . After a flight time of ninety minutes, the co-pilot reported to approach control in Basel. The control tower confirmed the position and reported the weather conditions on the ground. Accordingly, there was a wind speed of nine knots and a visibility of 700–1300 meters on the ground. The cloud ceiling was at a height of 120 m. It was snowing and the air temperature was zero degrees. The air traffic controllers instructed the pilots to descend first to the flight level 5000 feet and then to 4000 feet.

At 8:55:48 hrs GMT, the co-pilot reported that the aircraft had passed the outer marker, the BN radio beacon , of the instrument landing system . At this time, the air traffic controllers gave clearance for the descent to 2500 feet. Seventy seconds later the crew reported that they had sunk to 2,500 feet. Another minute later it reported that it had reached the MN radio beacon and received clearance for the approach to runway 16. After a loop, the pilots were given permission to land at 9:00:13.

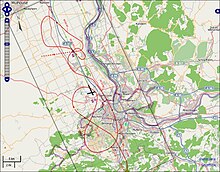

The pilot-in-command reported at 9:05:12 a.m. that he would take off and make another attempt to land. The control tower instructed the aircraft to approach the BN beacon again at an altitude of 2500 feet. Two minutes and 15 seconds later the flight crew reported that they had reached the beacon. The control tower then issued the instruction to head for the MN radio beacon. In fact, at this point in time, the aircraft was southwest of the airport, about 15 km south of the BN beacon.

The control tower received a call at 9:08:10 a.m. from a meteorologist from the Binningen weather station , about eight kilometers southeast of the airport. The meteorologist pointed out the air traffic controllers to a four-engine propeller aircraft that had flown only about 50 m above the ground over the meteorological station and requested that the crew be informed of the necessity of an immediate climb. During the phone call with the meteorologist, the flight crew of Flight 435 reported that they were flying over the MN radio beacon, which is located around 18 km north of the airport. Approach control then requested the aircraft crew to turn around and steer for the BN radio beacon on a south-south-west course. The subsequent evaluation showed that at this point in time, however, the pilots were not flying over the radio beacon BN around six kilometers north of the airport, but the radio beacon BS immediately south of the runway.

At 9:11:10 a.m., the Zurich control tower asked whether Basel was watching an aircraft heading towards Hochwald, as an unidentified echo appeared on the Zurich radar screen about three to five nautical miles southwest of Basel airport. The air traffic controller in Basel initially denied this, but then noticed an echo himself that was moving in a southerly direction. Flight 435 answered during this phone call and stated that the BN radio beacon had been reached. The control tower then cleared the landing.

After the phone call ended at 9:12:10 a.m., the air traffic controller tried to ascertain whether the Vickers was actually at the specified position, and at 9:12:33 a.m. the pilots confirmed that the machine was on the glide slope . At 9:13:03 a.m., the air traffic controller requested the current altitude of flight 435. The request was answered by the pilots with 1400 feet. The information from the air traffic controller that the aircraft was not on the glide slope but south of the runway was no longer answered by the crew because the aircraft was about 16 km at 9:13:27 a.m. (10:13:27 a.m. local time) crashed into a wooded mountainside of the Swiss Jura south of the airport .

Weather conditions

During the approach, the aircraft was almost constantly in the clouds. There was poor visibility due to the blowing snow. This was caused by a cold air mass flow from the North Sea towards the Mediterranean , which in the Rhine Valley led to the rise of warm air and thus to cloud formation and snowfall. The flying weather was therefore unfavorable because there was danger in the clouds from icing and turbulence, the strong north wind almost reached the ground and visibility was poor.

The official weather records for Basel for 8:45 a.m. show a slight rapid fall at 0 ° C and a cloud cover at a height of 120 m above ground and a runway visibility of 1300 m. At 9:15 a.m., i.e. immediately after the crash, the meteorologists recorded light snowfall at 0 ° C and a cloud cover of 150 m and a runway visibility of 1700 m. The conditions at the alternate airports in Zurich and Geneva resulted in sufficiently good or good conditions for a landing.

The range of vision on the runway was measured at two points, whereby at the decisive point at the time of the accident - between 9:03 and 9:09 a.m. - the range of vision fluctuated between 500 and 550 m.

According to witnesses, there was heavy snowfall at the crash site with a visibility of less than 50 m.

Aircraft

The Vickers Vanguard 952 was equipped with four Rolls Royce 512 Tyne engines and four De Havilland PD 223/466/3 propellers. The aircraft with the serial number 745 was ten years and eleven months old at the time of the accident. It had made its maiden flight on May 1, 1962. The aircraft had completed 16,367 flight hours, the engines had between 13,262 and 14,476 operating hours behind them. The last airworthiness test was from May 1972 and the last maintenance was carried out on March 24th.

crew

Both pilots had licenses that allowed them to fly as pilots-in-command. Captain Anthony Dorman, a Canadian citizen, had begun flight training with the Canadian Air Force in 1963, but it was discontinued due to lack of talent. In 1966 he had acquired a civilian license, which he later extended to commercial aircraft. In 1969 he was granted permission to pilot commercial aircraft in instrument flight in Nigeria on the basis of his Canadian pilot license and an allegedly successfully completed instrument flight test. However, during a later review it turned out that his flight logbook had not recorded such a test. He later passed instrument flight tests in the UK on DC-3, DC-4 and Vickers Vanguard aircraft. In each of these cases it took more than one attempt. The entire flight experience of Dorman could not be determined because discrepancies in the flight logbook of Dorman came to light during the investigation of the flight accident. For Invicta he flew 1088 hours on a Vickers Vanguard. He had landed 33 times in Basel, nine of them during an instrument landing.

The co-pilot Ivory Terry was a British citizen. He had started his flight training in October 1944 with the Royal Air Force and had flight experience of 9172 hours, 1256 hours of which on the type of the crashed aircraft. He had previously landed in Basel 61 times, 14 of them with an instrument approach.

Both pilots had flown together a total of 17 times, including twice to Basel, and on the day of the accident they had been on duty for around four hours and 45 minutes.

examination

The aircraft accident investigation was carried out by the Swiss Aircraft Accident Investigation Bureau (BFU). As is customary with aircraft accidents involving foreign aircraft, the aviation safety authority of the home country of the aircraft involved in the investigation with the Air Accidents Investigation Branch . Since Basel-Mulhouse Airport, including the facilities for the instrument approach, is located on French territory, the French authorities also sent observers to the investigation.

The investigation showed that on the one hand radio and blind flight instrumentation did not function properly, on the other hand there were training deficits among the pilots. The wrong reading of the radio compass , the lack of alignment with the second instrument and the pilot's lack of orientation may have led to the crash .

After the correct approach to the radio beacon BN, the radio beacon BN was approached again instead of the radio beacon MN. After the very sharp left turn, the U-turn to the west should possibly lead to BN, which the plane had already passed. Here the pilots swapped roles, with Terry as PiC. The target point of the approach was too far south and too far west. The first error was recognized, the second not. After going around and flying the loop, the escape axis was in line with the runway, but offset to the west by almost the distance BS-BN. Since no voice recorder was required in England for this type of flight, there is no explanation for the last few seconds. According to the investigation report, the machine was in a normal climb when it collided with the range of hills.

It was the worst aviation accident in Switzerland to date and the worst in the canton of Solothurn.

swell

-

Official investigation report in a translation by the Air Accidents Investigation Branch (PDF; English; 4.41 MB) ( Archive ( Memento from May 12, 2012 on WebCite )) (The original German text is not available online.)

- Attachments to the report (PDF, English; 3.89 MB) ( Archive ( Memento of May 12, 2012 on WebCite ))

- Accident report Vanguard G-AXOP , Aviation Safety Network (English), accessed on February 9, 2019.

- Text about the crash on Golfherrenmatt.ch

- Basler Zeitung from April 10, 2013 on the 40th anniversary of the crash

Coordinates: 47 ° 27 '15.1 " N , 7 ° 37' 23.5" E ; CH1903: six hundred thirteen thousand nine hundred and nineteen / 255949