Irish writing

The Irish script ( Irish cló Gaelach ), along with the other Celtic scripts and the Anglo-Saxon script, is one of the insular scripts , among which it is the oldest. It is a group of writings that were created in the insular area in the early Middle Ages and that were also distributed on the continent.

The Irish script is based on a Latin minuscule , the semi- uncial , and to a lesser extent the uncial . The reason for the predominant influence of the semi-uncials is that it was the writing of the vast majority of the codices brought from Gaul by the missionaries who Christianized Ireland in the 5th century . Ireland had never belonged to the Roman Empire and only entered the cultural area shaped by the Latin writing system with the penetration of Christianity. The books that came to Ireland in the course of Christianization were Bibles or contained liturgical , exegetical ,dogmatic or canonical texts. They were written in calligraphy . The starting point for the emergence of Irish writing was therefore not business correspondence written in italics, but precious manuscripts in semi-social script. Irish writing probably began in the second half of the 6th century, but the oldest written monuments, wax tablets from an Irish peat bog, were probably not made until the early 7th century.

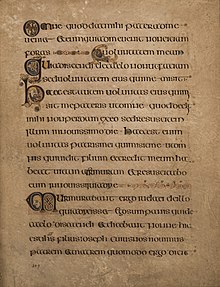

The oldest form of the Irish writing is a semi-uncial, which is referred to as "Irish circular" or "insular circular". It differs from the continental semi-uncial in the pronounced curves, the reinforcement of the tips of the ascenders and the straight lines of the middle letters by triangular, spatula-shaped approaches, the small extension of the ascenders and the strong curvature of the shafts of b, d, h and l . The typeface is compact, one spoke of litterae tunsae ("shaved letters"). The circular can be found mainly in magnificent manuscripts. In the 7th century the "Spitzschrift" or "insular minuscule" was developed, which saved space and enabled faster writing. It strongly weakened the peculiarities of the circular; the triangular approaches are less pronounced. The letters in pointed script are narrower and usually more closely packed than those in circular script and are often very small; the descenders run out in fine points. Ligatures and abbreviations are common. The Irish developed a special, characteristic system of abbreviations in cursive script . Irish-language texts were written almost exclusively in cursive. From the 9th century the circular was used less and less, from the 12th century it was not used at all. The pointed script, on the other hand, was preserved throughout the Middle Ages.

Of the magnificent manuscripts written in circular script, the Book of Kells , created around 800, is the best known. The Book of Armagh, written at the beginning of the 9th century, is an example of pointed script .

The Irish writing system spread far beyond its area of origin. It came to Britain through the Irish mission in Northumbria from 634 and through the many Anglo-Saxons staying in Ireland for many years . An Irish-Northumbrian calligraphy and book art developed. From the end of the 6th century, Irish monks brought their script to the mainland in the Frankish Empire . Due to the mainland scriptoria , which was influenced by Irish influence, the Irish writing system spread in what is now France, in German-speaking countries and in northern Italy.

The use of the Irish script in book printing began in 1571 with a type that was commissioned by Queen Elizabeth I of England for the printing of an Anglican catechism ("Queen Elizabeth's Type", cló Éilíseach ). Another type was created by Catholic monks who lived in exile in Belgium. From the 17th century, the Irish script was a symbol of the will to preserve the cultural independence of Ireland. It was used as the common font for texts in the Irish language until the 20th century. Today it is used almost exclusively for decorative purposes.

In Irish printing, lenited consonants are not identified by a trailing h as in modern antiqua , but by a diacritical point (ponc séimhithe) , which emerged from the punctum delens ( deletion point for spelling errors) of medieval manuscripts, that is: ḃ ċ ḋ ḟ ġ ṁ ṗ ṡ ṫ instead of bh, ch, dh, fh, gh, mh, ph, sh, th; for example amaċ instead of amach (Irish for “out”). This is facilitated by the lack of ascenders in the corresponding Irish grapheme characters . Another characteristic of the Irish print is the frequent use of the Tironic et for the shortened spelling of the word agus (Irish for "and").

literature

- Bernhard Bischoff : Palaeography of Roman antiquity and the western Middle Ages . 4th edition, Erich Schmidt, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-503-09884-2 , pp. 113-122

- Hans Foerster, Thomas Frenz: Outline of the Latin palaeography. 3rd, revised edition, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-7772-0410-2 , pp. 141-146

- Ann Lennon, Graham P. Jefcoate: Irish writing . In: Lexicon of the entire book industry. 2nd, completely revised edition, Volume 4, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-7772-8527-7 , pp. 32–34

Web links

- Dianne Tillotson: Medieval writing

Remarks

- ^ Hans Foerster, Thomas Frenz: Abriss der Latinischen Paläographie , 3rd, revised edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 143; Bernhard Bischoff: Palaeography of Roman Antiquity and the Occidental Middle Ages , 4th edition, Berlin 2009, p. 113.

- ↑ Bernhard Bischoff: Palaeography of Roman antiquity and the occidental Middle Ages , 4th edition, Berlin 2009, p. 113; Hans Foerster, Thomas Frenz: Abriss der Latinische Paläographie , 3rd, revised edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 144.

- ^ Hans Foerster, Thomas Frenz: Abriss der Latinischen Paläographie , 3rd, revised edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 144 f .; Bernhard Bischoff: Palaeography of Roman Antiquity and the Occidental Middle Ages , 4th edition, Berlin 2009, pp. 116 f., 119.

- ^ Hans Foerster, Thomas Frenz: Abriss der Latinischen Paläographie , 3rd, revised edition, Stuttgart 2004, pp. 145–147; Bernhard Bischoff: Palaeography of Roman Antiquity and the Occidental Middle Ages , 4th edition, Berlin 2009, pp. 114, 120.