Anglo-Saxon script

The Anglo-Saxon script, along with the Irish script and other Celtic scripts, is one of the " insular scripts " that were created in the early Middle Ages in the insular region ( Britain and Ireland) and that were also spread across the continent. The oldest insular script is Irish, which probably began in the second half of the 6th century. From it the Anglo-Saxon developed in the 7th century. Because of their close relationship, they are not easy to tell apart.

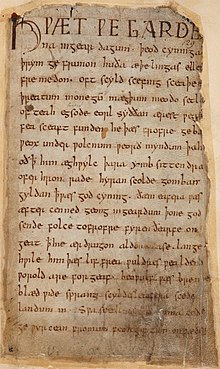

The basis for the emergence of the insular scripts was the continental semi-uncial , a minuscule that was used for precious ecclesiastical books. An Irish semi-uncial was first developed from it in Ireland, which is known as the "insular circular" because it is mainly characterized by pronounced curves. This compact font was primarily used for calligraphically designed manuscripts. In the 7th century the Irish developed the “Spitzschrift” or “insular minuscule” from it, which saved space and made writing easier. Both scriptures spread throughout Britain including the Anglo-Saxon areas. The Anglo-Saxons became familiar with the Irish writing system through the Irish mission in Northumbria from 634 and through the many Anglo-Saxons staying in Ireland for many years. An Irish-Northumbrian calligraphy and book art developed. The Lindisfarne Monastery , an important center of Celtic monastic culture in the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria, played an important role . It was there that the Book of Lindisfarne , which is one of the oldest Anglo-Saxon manuscripts , was created around 700 . In Northumbria, the two Irish scripts were further developed into Anglo-Saxon circular and pointed script. For Old English texts, the letter wynn (ƿ) was added from the runic alphabet ; the th was represented with ð or with the Thorn rune (Þ). The Anglo-Saxon script spread from Northumbria to the southern kingdoms of England.

The Anglo-Saxon scribes adopted the main features of the Irish scripts, including the spatula-shaped shaft approaches. The delimitation of the products of Anglo-Saxon and Irish writing schools is difficult , even for experienced palaeographers . Irish scribes tended to have more angular, broken shapes, while English scribes tended to be more rounded.

The Anglo-Saxon circular was a pure book font. Its heyday fell in the 8th century and was used until the 10th century. In Rundschrift were magnificent codices written, including the Gospels of Canterbury and the Liber Vitae of Durham , a brotherhood book . In the 9th and 10th centuries the circular script was replaced by the pointed script, which was used for books as well as for other purposes - especially as document script.

Anglo-Saxon monks who were active on the mainland brought their script to the Frankish Empire . The Anglo-Saxon script was used in the scriptoria of the continental monasteries they founded. In the 8th and early 9th centuries it experienced a heyday in the German-speaking world. Local scribes were trained who were guided by the insular patterns. Important centers were the Echternach monastery founded in 698 by the Northumbrian missionary Willibrord and the Fulda monastery founded in 744 on behalf of Boniface . In the course of the 9th century, however, the Anglo-Saxon script was pushed back and finally replaced everywhere by the Carolingian minuscule . She stayed the longest in Fulda, which was her last base from around 820 onwards. In the second half of the 9th century it died out there too.

In England, continental influence increased from the 10th century, with Cluniac monks from the mainland playing an important role. The Anglo-Saxon script incorporated continental elements. The Carolingian minuscule prevailed for Latin texts, whereas the Anglo-Saxon script was able to hold its own for a long time in English texts.

literature

- Bernhard Bischoff : Palaeography of Roman antiquity and the western Middle Ages . 4th edition, Erich Schmidt, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-503-09884-2 , pp. 122–129

- Hans Foerster, Thomas Frenz: Outline of the Latin palaeography. 3rd, revised edition, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-7772-0410-2 , p. 146 f., 150–152, 158

Web links

- Dianne Tillotson: Medieval writing

Remarks

- ↑ Bernhard Bischoff: Palaeography of Roman Antiquity and the Occidental Middle Ages , 4th edition, Berlin 2009, pp. 114, 122–124; Hans Foerster, Thomas Frenz: Abriss der Latinische Paläographie , 3rd, revised edition, Stuttgart 2004, pp. 143–147.

- ^ Hans Foerster, Thomas Frenz: Abriss der Latinischen Paläographie , 3rd, revised edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 147.

- ^ Hans Foerster, Thomas Frenz: Abriss der Latinische Paläographie , 3rd, revised edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 147; Bernhard Bischoff: Palaeography of Roman Antiquity and the Western Middle Ages , 4th edition, Berlin 2009, p. 125.

- ↑ Bernhard Bischoff: Palaeography of Roman antiquity and the occidental Middle Ages , 4th edition, Berlin 2009, pp. 126–129.

- ↑ Hans Foerster, Thomas Frenz: Abriss der Latinischen Paläographie , 3rd, revised edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 151 f.