Descent from the Cross

The Descent from the Cross of Jesus is described in the New Testament in Joh 19.38–40 EU , Mk 15.42–47 EU , Lk 23.50–56 EU and in apocryphal writings. According to these testimonies, Joseph of Arimathea and, according to John, Nicodemus also take Jesus from the cross.

Different views of the biblical narrative

The fact that it was not two of the twelve disciples who did the last love service to the Lord, but two completely different personalities, who had hardly played a role until then, is a riddle. In the third chapter of the Gospel of John Nicodemus' famous conversation with Christ is described, in which he asks the question: "Lord, how do I gain eternal life?" Christ's answer that he must be born a second time, namely from Water and Spirit, is most commonly understood to mean that he should be baptized. He must go into himself, repent and make the decision to start a new life . Before that, he should go through water baptism, the experience of which could strengthen him in the decision made.

Since the 9th century at the latest, important Christian theologians such as Radbertus von Corbie have interpreted the burial as meaning that the grave in which the body of the Lord is laid is the heart of man. In his commentary on Matthew, he gives the justification: Because without Christ man would be hollow and empty. Only Christ gives the human soul its central meaning. Others today also point out that “being born a second time” was also a common term used in late ancient mysteries.

Joseph of Arimathia can also be put into such a context. The early Christian apocrypha portrayed him as the founder of a special stream of Christianity, to which Christ had given the cup with the blood of Christ in prison. Taught for weeks in dungeon by the resurrected one, he had become the founder of Grail Christianity. These ideas were common property of the culture of their time through the medieval Grail novels and must be taken into account when interpreting medieval representations inherent in the work.

The Descent from the Cross in Art

Depictions of the Descent from the Cross have appeared in Byzantine and Western art at the same time since the 9th century. Walther Matthes and Rolf Speckner were able to present a list of 246 representations for the period between 820 and 1300, which can certainly be expanded. The representations are distributed over this period in such a way that two to three are from the 9th century, twelve are said to have been made in the 10th century, and another five are dated “around 1000”. 27 were made in the 11th century, eight around 1100, 67 in the twelfth, another seven around 1200, 106 in the 13th century, and finally eleven are dated around 1300. If you distribute the inaccurate dates 'around the turn of the century', the result is about a doubling rate from century to century. From the 14th century on, the material becomes difficult to overlook. Special examinations are missing.

However, some basic trends can be outlined. The oldest representations that are reasonably dated are two book illuminations from the west and east of Europe, possibly with a stone relief. Why interest in this event awoke in the 9th century is unknown. Some book illuminations, Byzantine wall paintings and a few western ivory reliefs have survived from the 10th century. The Reichenau School, which began in the 10th century, continues in the illumination of the 11th century. For the first time an ivory sculpture appears as well as wooden reliefs, stone reliefs and metal reliefs of the Descent from the Cross. The 12th century produced an abundance of stone sculptures, other book illuminations and wall paintings. No other stone reliefs were created in the 13th century; they were replaced by wooden and partly movable sculptural groups. A great abundance and variety of book illuminations emerged and, in addition to many wall paintings, the first panel paintings. The stream of panel paintings from Western Europe flowed through the centuries and reached its peak in the 15th and 16th centuries. Icon images of the Descent from the Cross have also been made in the East since the end of the 13th century. Finally, the production of wooden reliefs reached another high point around 1500.

The oldest representations in Byzantine art

The oldest known Byzantine depiction can be found in the Codex Grec. 510 made for Basil I as a miniature painting. It is said to have originated in the sixties or eighties of the 9th century. In the representation, the nail solution comes to the fore, as the Greek word for the Descent from the Cross, apokathelosis, suggests: it means 'nailing off'. Nicodemus pulls the nail from Christ's hand on the left with powerful pliers. In the middle, Joseph of Arimathea, approaching from the right, embraces the body of Christ to carry it. The already released left hand of Christ lies on Joseph's shoulder. To the right behind him are Maria and Johannes, the witness. Maria seems to clench her hands under her chin. The sun and moon can be seen above the crossbar . What is striking is the sculptural shape of the small figures. A late antique style asserts its influence. Does this point to older role models?

In Toquale Kilisse near Göreme in Cappadocia an early wall painting has been preserved, which was painted around 910-920 in a cave church. Joseph of Arimathia embraces the oversized body of Christ in both arms and takes it on his shoulder. Christ's head has a full beard. Long tears of hair flow down his shoulders. The already detached arms of Christ hang down long over Joseph's back; Mary, standing behind the white-headed man, holds Christ's arms. His head, which is surrounded by an aura of the cross, has barely fallen forward and touches the crown of Mary. Christ wears a short skirt with a central fold around his loins. Nicodemus bends down and uses small pliers to remove the nails from the trunk that had pierced the feet. Like Mary, he has a halo. The moon above the right crossbar suggests a cosmic meaning of the event. At the point where the sun is expected above the other crossbeam, the Greek painter has placed the head of Christ.

In the culturally Byzantine area, painters' books were written in the Middle Ages that stipulate what should be painted in detail. In the East, a tradition of a few ways of designing the topic is quickly developing. As far as the influence of Greek Orthodoxy extends, for example from Sinai to Serbia, these forms have been handed down for a long time. Greek works influenced northern Italy (Aquileia, Venice, Rimini) and the western way of depicting the Descent from the Cross.

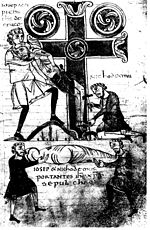

The oldest representations in Western Europe

In the west, it seems that the Descent from the Cross was depicted a little earlier. The oldest, reasonably dated representation is an illumination in the Breton Codex of Angers. Gertrud Schiller dates the picture to the middle of the 9th century. Here Joseph stands on the left and embraces the already detached upper body of Christ. By placing his foot on a wave of the earth, Joseph can support Christ's body with his knee. Nicodemus kneels at the feet of the cross and knocks out the nail with a hammer. The names of the two are also written: iosep accipiens ihs de cruce stands above the head of the left figure, and directly next to the neck in smaller letters: iste iosep . Nichodemus is standing above the kneeling nail-loosening figure on the right . Wherever in the Middle Ages the names of those performing the Descent from the Cross are mentioned, it is Joseph who carries the body, while Nicodemus takes on a helping role. The widening ends of the cross arms, which are reminiscent of elastic calyxes, are striking. The cross, the sign of death, bears the signs of new life on it. In the middle, where the bars meet, is a circle with nine spirally arranged leaves inside. It is the room where the heart of Christ suffered the pain of the crucifixion. The sun and moon stand above the crossbar, depicted as mighty circles, inside of which also leaves, albeit only six, seem to be in a spiral movement. The depiction of the Angers Codex lacks John and Mary. This creates a calm concentration on the only important process. In a lower scene separated by a line, Joseph and Nicodemus carry the wrapped body of Christ to the grave. The different nature of the presentation suggests that the representations made in the same period are largely independent of one another.

The Reichenau School

In addition to these two starting points for artistic representation, a third mode of representation came a hundred years later, which became school-building, namely that of the Reichenau painting school . The actors' environment is reduced to the slightest in the representation. A delicate inwardness characterizes these works, which the other two schools lack. A central work of the same is the Egbert Codex , created after 980 , which was created by the Reichenau monks Kerald and Heribert for the Archbishop of Trier Egbert. Among other things, it contains a picture of the Descent from the Cross, bathed in a dreamlike atmosphere of deep silence. (KA 13) The cross is painted low enough that no ladder or chair is needed. Both men stand dignified and upright and together hold the body of Christ. Josef puts it straight over his shoulder, Nicodemus carries his legs. The cross is unadorned. The men seem lost in their work. The calm concentration on the essentials makes the deep seriousness of the action present.

Another representation from this school (KA 5) is in a Fulda sacramentary in Göttingen. The same magical silence speaks to the viewer from this picture. Here it is only one person who carries out the acceptance, so probably Joseph of Arimathia. From the right the disciple approaches the cross and just lets the arms of the heavy body slide over his right shoulder. Joseph has a halo that z. T. covers the face of Christ. As small as it is, the representation is very lively. Joseph gets up on his tiptoe to receive the Lord. To the right of it, grouped together with the acceptance by a common frame, the burial is shown, in which the body of the dead is carried by both disciples. Another sacramentary is kept in Udine (KA 14). Its depiction of the Descent from the Cross is so similar to the aforementioned Fulda sacramentary that both may come from the same workshop, possibly from Fulda . In Bamberg there is another Fulda sacramentary, which embodies the Descent from the Cross (KA 21) in this way.

Other representations follow the Egbert Codex, according to one of Otto III's gospels. (KA 17) and a gospel book of Heinrich III. (KA 23). Three scenes are here united on one sheet. The upper half fills a crucifixion, below it is the acceptance on the left and the entombment on the right. Above the last two is ligno depositus a iusti fitqi sepultus . The serious silence begins to be displaced by the diversity of what is represented. The body of Christ has lost all weight: it is easily lifted up by the two faithful disciples. A Gospel Book of Emperor Otto III from the Aachen Cathedral Treasury (KA 16), which was created around 1000, is also attributed to the Reichenau School.

Representations of the 11th and 12th centuries

During the 11th and 12th centuries, the number of Descent from the Cross increased steadily. It is mainly book paintings that are made. Ottonian book paintings can also be found in what is now western Poland, in Gniezno (Gnesen). A codex was created around 1085 whose Descent from the Cross (KA 27) takes up a third of a page. Nicodemus is shown oversized, steps from the right to the cross and hands the body to Joseph, who is on the left. Nicodemus' ruling figure emerges here like nowhere else like a king. By the way, there are only three women left, Johannes cannot be seen. Because of its iconography, this image has a peculiar special position.

The second Gnesen representation (KA 73) is dated around 1160 and is attributed to Roger von Helmarshausen or his school, which was based in the Weser area. The painted frame reveals the familiarity with the goldsmith's Niellotechnik. Nicodemus uses a ladder and lowers the body of Christ from above onto Joseph's shoulders. Although he has climbed the ladder, Nicodemus holds Christ's left while Mary carries his right to the left of the cross. Behind Maria stands Johannes on the far left.

One of the most beautiful depictions of the Descent from the Cross was made shortly before 1100. It is a stone relief in the cloister of the Santo Domingo monastery in Silos (KA 42). Joseph of Arimathia came up to the cross from the left and put his arms around the body of the Lord. Behind him stands Mary, who presses the right hand of Christ to her cheek. Nicodemus stands to the left of the cross and turns his back to the Lord. He pulls the nail out of his left hand with pliers. Finally, on the far right, Johannes is standing with a book in his arms; his whole body is in motion. John and Mary have a halo, while Joseph and Nicodemus do not. Christ also has a great aura with a cross in it. Over the cross, three angels waving cokes. The sun and moon appear personified and hide behind scarves. Under the cross is a box, indicated by the letters ADAM as his grave. The letter M is designed as a small tree of life. Adam himself looks up from the grave and holds the lid. All around him are clods of earth, the irregular surface of which looks like a sea.

The relief of the Descent from the Cross on the Externsteinen , which has been ascribed to the 9th and 12th centuries alternately since Goethe's time, is located on the Externsteinen , a sandstone group in the Teutoburg Forest. It is the largest sculpture that has been carved into the rock under the open sky in Europe. Lately a wealth of points of view have been asserted that this relief should also be one of the oldest representations from the 9th century.

Another outstanding Romanesque sculptural work is a capital that was also made in Spain, namely in Pamplona, about 40 to 50 years later (KA 103). The structure of the scene is almost identical to that in the monastery of Silos: Joseph approaches the Lord from the left and puts his hands around his body, who has already begun to lean to one side. Maria takes hold of the already loosened left arm, Nicodemus loosens the right one with powerful pliers. Above the cross you can see two angels carrying the sun and moon. The finely trained robes of the two actors deserve special attention. Their energetic actions seem to lift them from the ground, as if they were filled with a mighty upward movement. Nicodemus supports himself with one foot on a small tree of life that sprouts close to the base of the cross and resembles the one on the relief in silos. Relationships with the relief on the external stones cannot be overlooked.

Representations of the late Middle Ages

The number of depictions of the Descent from the Cross continues to increase up to around 1500. In particular, panel paintings now appear in addition to the relief work and fully plastic wood representations, a late example may be the Descent from the Cross of the great altar by Rogier van der Weyden. Furthermore, the scene is included in the books of hours from the beginning .

literature

- Edgar Hürkey: The image of the crucified in the Middle Ages. Investigations into grouping, development and distribution based on the garment motifs . Worms 1983, ISBN 3-88462-021-5

- Walther Matthes / Rolf Speckner: The relief on the external stones. A Carolingian work of art and its spiritual background . edition tertium. Ostfildern 1997, ISBN 3-930717-32-8 . Classes the Descent from the Cross at the Externsteine in the development of the depiction of the Descent from the Cross. List of 246 representations, 30 of which are shown, e.g. T. quite small.

- Elizabeth C. Parker: The Descent from the Cross. Its Relation to the Extra-Liturgical 'Depositio' Drama. Diss. New York University. June 1975. Garland Publishing. New York and London 1978, ISBN 0-8240-3245-4

- Erna Rampendahl: The Iconography of the Descent from the Cross from the 9th-16th centuries . Diss. Berlin 1916. This 90-year-old dissertation is not up to date with regard to the completeness of the cited works, their locations, dates, and often also allocation. But there is no newer iconography of the Descent from the Cross in German.

- Bernd Schälicke: The Iconography of the Monumental Deposition Groups of the Middle Ages in Spain . Diss.FU Berlin 1975. Berlin 1977.

- Gertrud Schiller : Iconography of Christian Art. Volume 2: The Passion of Christ. Gütersloh 1968.

- oA: Descent from the Cross . Translated from English. Phaidon Verlag, Berlin 2005, ISBN 0-7148-9460-5 . The small illustrated book contains 104 color images of the descent from the cross from 9th to 20th Century; Comment extremely tight.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Pascasius Radbertus. In expositio Matthaei. Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio Mediaevalis. Turnholti. Vol. S.

- ↑ Hella Krause room. Cross and resurrection. Traces of mystery in Passion and Easter portraits. Stuttgart. 1980

- ↑ The Gospel of Nicodemus. In: Hennecke-Schneemelcher. Apocrypha 1968. pp. 330-358.

- ↑ Robert de Boron. The story of the Holy Grail. Translated from the French by Konrad Sandkühler. 3rd edition 1979. Robert de Boron's work was written shortly before 1200.

- ↑ In the following descriptions, the numbering according to Matthes / Speckner is used as KA 1 - KA 246 in order to have a clear reference point.

- ^ Paris. Bibl. National, Ms.grec. 510, fol. 30 v. Mattes / Speckner KA 3.

- ^ Gertrud Schiller: Iconography of Christian Art . Vol. 2. Gütersloh 1968

- ^ Thomas Mathews and Avedis K. Sanjian: Armenian Gospel Iconography. The tradition of the Glajor Gospel . Washington 1991.

- ^ KA 11 (Matthes / Speckner). Gabriel Millet, " Recherches sur l'Iconographie de l'Evangile aux XIV., XV., Et XVI.siecles ", Paris 1916, 1960², dated 913; Elizabeth C. Parker, The Descent from the Cross, New York-London 1978, dated 910-920.

- ↑ Angers. Bibl. Municipale. Cod. 24. Fol. 8. Maybe from Lorraine. Hürkey takes on Byzantine influences.

- ↑ Franz J. Ronig. Codex Egberti. Archbishop Egbert von Trier's pericopes. Trier 1977

- ↑ Trier. Library. Cod. 24, fol. 85v.

- ↑ Göttingen, University Library, Ms. 231, fol. 64r

- ↑ Munich Clm 58, Ms.lat.4453. Around 1000 (Leidinger).

- ↑ University Library of Bremen, cf. JMPlotzek The Book of Pericopes

- ↑ Walther Matthes / Rolf Speckner: The relief on the Externsteinen. A Carolingian work of art and its spiritual background . edition tertium. Ostfildern. 1997